By James Longhurst

In 1979, a plainclothes police officer assaulted a uniformed parking agent in broad daylight on the steps of the courthouse in lower Manhattan. The New York Times summarized the fight between the policeman and the female parking enforcement agent, declaring that “the two were screaming at the top of their lungs. There was a bit of a scuffle. Both somehow ‘tripped’ (as the police later put it), and the meter maid suffered a cut knee. Officer Curtin arrested the meter maid and hustled her into the back seat with a couple of criminal suspects.” [1] In the aftermath, the police and the traffic department launched competing inquiries. The story is astonishing, recounting a physical attack on a uniformed officer on a public stage, and treating it as a joke. What could be so important, so divisive, so reality-warping that it would bring two agents of the public to blows on the courthouse steps? The answer, of course, is parking. The history of parking provides a remarkable exposition of who has the privilege of occupying urban space, and who does not.

Urban history needs a new approach to parking. This most mundane of practices is key to transiting the city, and is both an enabler and obstacle to urban mobilities. As a practice that intrudes upon countless lives, it occupies a constant and outsized portion of public space, and serves as a bone of contention in nearly all zoning and planning debates. Thus, a human history of parking can tell us a great deal about publics, society, and power. By “human history,” I mean the lives of people shaped by unequal constraints on movement; Genevieve Carpio calls this the study of “the everyday channels of movement in a community.”[2] Parking determines access to physical space in the city and an unequal ability to move through the demographic and economic boundaries of neighborhoods and suburbs. It also provides an excuse for the regulation of these liberties through expanded police power.

As the opening piece to The Metropole‘s Moving the City series notes, “in many ways, urban transit reflects American society’s class, racial, and gender inequalities.”[3] This is true of all mobility modes: walking, riding public transit, driving an automobile. Even the bicycle became “a symbol for all sorts of other political debates about who belongs where,” as Evan Friss has argued.[4] This phrase – “who belongs where” – is key to understanding the importance of urban transit; it demonstrates who has the privilege of free and unregulated movement in cities; whose movement is prioritized over others; and the power of those doing the regulating. Like those other modes, parking should also be understood as a part of transiting the city.

Inspired by recent work of scholars including Sarah A. Seo and Genevieve Carpio, I propose a new history of parking that takes into account the human impact of the ordering and policing of urban mobilities.[5] Others have already examined parking as a subject; many of their accounts, however, either treat parking as a humorous subject – the perennial gripe of shoppers, urbanites and university faculty – or have focused on the architecture, physical layout or planning of the urban form, with special emphasis on suburbanization.[6] But a new history of parking might include topics like the risky work environments of crossing guards, unexpectedly vicious disputes over communal streetspace lost to parking, and daily jostling for neighborhood space.[7] As one topic from this list, I’ve recently been drawn to the largely-untold history of parking enforcement, and the internal debates over who would be assigned this low-status work. The history of parking enforcement demonstrates class, racial, and gender inequalities through both the subjects and the agents of regulation. Once known by the casually sexist term “meter maid,” parking enforcement officers were a part of determining who had the privilege of occupying the public street.[8]

Plentiful Parking: Understanding the Street as a Commons

When it comes to parking, the socio-technical system of the public street is best understood as a commons, or an imperfectly shared common-pool resource.[9] In a legal sense, the “public street” is not a physical place, but a right of movement – a “right of way” – imposed as an easement on private property rights; in general, municipalities do not “own” the physical property of the street. This easement is a commons meant to serve the public good. It is a publicly-controlled network for the free movement of people and goods, transported by many means: in pipes, over wires, on foot, on tracks, or on wheeled vehicles of all descriptions. Legally, governments and their agents were empowered to regulate the various uses of this easement in order to ensure the free flow of goods and people. As with all “public goods,” however, the street engenders debate over exactly who was included in the public, who was privileged to enjoy a share of the goods, and what was a just distribution.

Within this legal context, leaving one’s private property blocking the common space intended for the free movement of people and goods was largely banned before the 20th century. In 1889, an American court declared that “the highway may be a convenient place for the owner of carriages to keep them in, but the law . . . prohibits any such use of the public streets.” This decision echoed the long-standing philosophy of the road by stating that “the primary use of the highway is . . . the passing and repassing of the public, and it is entitled to unobstructed and unoccupied use of the entire width of the highway for that purpose.”[10] Before the 20th century, horse-drawn carriages and wagons could not be abandoned in the street; their storage (and the feeding and maintenance of their horse-power) necessitated an entire industry of private livery stables and yards.[11] Leaving one’s personal property unattended in public space was as unthinkable as storing one’s suitcases in the lobby of city hall. But the booming popularity of personal automobiles led to widespread public acceptance of leaving idled vehicles on the grassy, park-like verges of public roads. “Parking” is just another word for “temporary street storage of private property at public expense.”

As Peter Norton has argued, the arrival of the private automobile hit cities as a crisis of outrage and public safety, quickly demanding response from authorities.[12] Early-20th-century metropolitan police forces resisted the responsibilities of traffic and parking enforcement, seeing both as discrediting their goals of professionalization through crime fighting. Eric Monkennen advanced this periodization of police history, summarizing an argument for the turn-of-the-century shift from prioritizing a “public order” mission to prioritizing the more rhetorically-persuasive mission of “crime control.” As Monkennen puts it, “by the end of World War I, police were in the business of crime control. Other city- or state-run agencies had taken over their former noncrime control activities.”[13] Emerging at the exact moment that they were trying to distance themselves from day-to-day management of public order, the problems of “traffic” management were unwelcome to police forces.

The Birth of the Meter Maid

Cities that instituted traffic control regimes “quickly ran into an enforcement problem: everybody violated traffic laws,” as Sarah A. Seo notes.[14] Traffic enforcement would thus be an unending, daily, continuous process; scooping up the powerful and the powerless alike and exposing them to the unequal mercies of municipal courts. As a part of this enforcement, parking and its regulation would be a constant wellspring of petty but fearsome disputes, marked by physical threats, daily evasions and inequities. Who had gotten their fair share, who had insufficient street privilege to claim more, who had the status to claim coveted space, and who could possibly possess sufficient authority to tell everyone their place in the hierarchy?

While the police reluctantly struggled to control parking through the first half of the 20th century, the issue became more pressing after overnight street parking was legalized in cities during the 1950s. Some police forces had tried for decades to delegate parking enforcement to civilian auxiliaries or other city employees who would not have police power of arrest, and would later be excluded from membership within police unions. But the 1950s legalization of overnight street parking demanded daily regulation. Without the overnight policy to keep a lid on things, street parking would have to be actively regulated by a much larger force of humans. Heralding this transition, the New York Times announced in 1959 that “the Traffic Department plans to have a force of 100 women on the job about next Jan. 1 to police parking at the city’s 50,000 meters.”[15]

The language surrounding the post-war appearance of the often-female parking “attendant” is important. Parking enforcement would not be the work of the militaristic, armed and respected police officer, sworn to fight crime, but instead a domestic servant – a meter maid, or parking attendant, distinguished by uniquely gendered uniforms, vehicles, and powers. The parking enforcement workers would eventually come to embody urban divisions of race, class, and gender.

Journalistic coverage of the newly-hired women doing the daily work of parking enforcement captured the conflict between downtown businessmen and the female agents of public authority, while simultaneously diminishing that authority. One series of stories from the Washington Post captured a physical assault on a parking enforcement officer, even while downplaying the seriousness of the incident – a businessman’s assault on “a persistent parking meter maid” is described in passive voice as a mere “tiff”: “When Mrs. Dawson tried to put the ticket under the windshield of the car, [Burkes] pushed her away and she fell down.”[16] The jeweler eventually got a $50 fine and a lecture from a judge.[17] But a similar $50 fine was reversed by a New Jersey appellate court. This time, the “harassment began after Betty Jean Seth, the meter maid, had ticketed Mr. [Joseph Weber Jr.’s] car for overtime parking.” Weber retaliated by trailing Seth for thirteen days and “sarcastic remarks to her and to passers-by about her work.” The thirteen days of harassment, however, was determined by the court to be “childish but . . . not a crime.”[18]

Perhaps more surprisingly, other clashes arose when the new parking regulators began to infringe on the assumed prerogatives of sworn police officers. One 1960 story alleged that New York cops “were issuing summonses to meter maids in retaliation for parking tickets the women issued to private cars owned by policemen.” The officers had come to believe that “certain metered spaces near police stations had been considered ‘safe’ if the vehicles displayed a sign,” and so assumed that the new parking regulations did not apply to their vehicles; the origins of a custom that continues to this day in New York as the parking “placard.” At the time, the police retaliated, writing $10 tickets that the parking enforcement employees were forced to pay. Despite the conflict, “a Traffic Department spokesman discounted reports of a feud” between the two groups of municipal employees.[19]

The two groups of city employees were still scrapping a decade later, and reporters covered a slow-motion avalanche of aggression and reprisal. After Parking Enforcement officer Corrine Bryant ticketed Patrolman Thomas Sinacore’s car in 1972, he complained: “but I’m a policeman on duty …You can’t give a summons to a police car.” Pointedly referring to Bryant by her given name and Sinacore by his surname, the journalist recounted how, “with an oh-can’t I gleam in her eye, Corrine wrote out a summons and affixed it to the windshield.” Calling for backup, Sinacore “snapped a pair of handcuffs on the maid,” which “brought cries of protest from a passing pedestrian,” who in turn soon found herself handcuffed next to Bryant.[20] A week later the Police Commissioner and Traffic Commissioner were still exchanging angry letters over the incident.[21]

Seven years later, a similar conflict led to blows on the courthouse steps that opened this essay, diminished in the article as a “scuffle.” It all began when the parking enforcement agent, “Officer Fields[,] announced that [the police officer] could not park in the no-parking zone. Officer Curtin, who was in plain clothes, insisted he was on police business and, according to a police spokesman, demanded to see the identification of the meter maid, who was in uniform.” Indeed, “words led to louder words. There was some bumping and an unseemly scuffle, as one officer put it, then the improbable double tripping.”[22] The internal hierarchy of municipal employees was enforced in public view, on the courtroom steps.

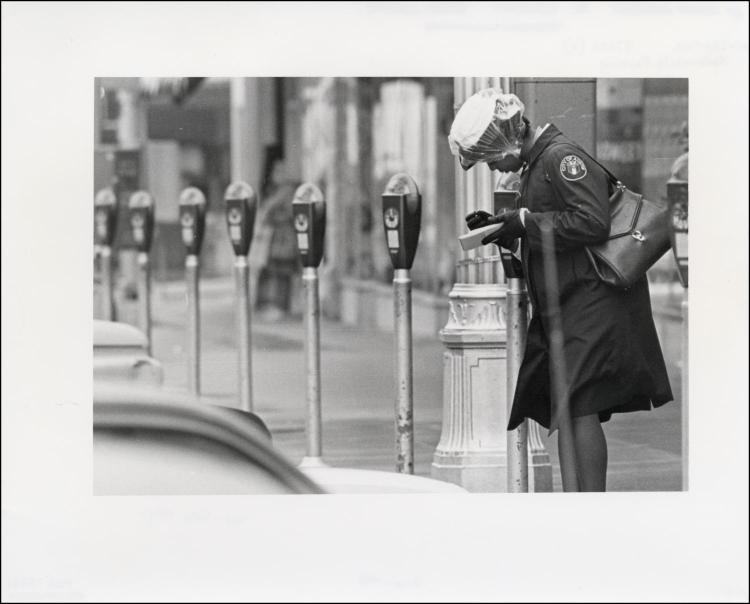

Along with these journalistic accounts, photographs of the new parking enforcement authorities provide complementary archival evidence. The publicity photos document several themes, including a diminution of authority through establishing gender-specific uniforms and task-specific vehicles. Photographers posed parking enforcement in ways that emphasized their uniform skirts and low-speed vehicles, often contrasting them with boot-wearing male motorcycle officers. The captions themselves delineate gender boundaries; one photograph titled “Keeps her powder dry” is captioned: “Mrs. Irene Loeser, … starts off new job as parking control checker in typical feminine fashion by powdering her nose. Waiting with good humor to show her ropes is her husband, Skip.”

The photographic record also captures the reality that parking enforcement was a pathway into public employment for women of color, and capture undeniable pride on the faces of those women who were photographed for newspaper or promotional purposes. A 1960s portrait from the collection of legendary photographer Charles “Teenie” Harris captures “Willa ‘Kitty’ Chandler, the first African American meter maid police officer in the city of Pittsburgh.” Twenty years later, another photo points to the need for further research into municipal employee organizing. Even as the term was falling out of favor within public service, newspaper photos depicted African American women but the caption still described “Philadelphia meter maids attend[ing] a hearing . . . as they try to get their jobs back.”[23] The story of how majority-female parking enforcement agents ended up excluded from police unions is most likely another measurement of the human inequalities of parking history.

Conclusion

The subject of parking is like a thread running through the history of the 20th century city. Without parking at the terminus, the suburbanization of the postwar era could not have reorganized the lives of Americans into new demographic enclaves. Parking made possible the political divide of urban cores against suburban communities, the supermarket revolution, the ennui of suburban housewives and the excesses of exurban sprawl. Parking demands near downtown employers fueled urban renewal projects that paved over entire neighborhoods, often eliminating African American communities in order to serve suburban commuters. At the turn of the twenty-first century, parking minimums and auto-centric planning policies helped foster a housing market that squeezes the millennial generation out of home ownership opportunities.[24]

Throughout the 20th century, the phrase “street privilege” came to mean the granting of special right to a user who asked to take a larger share of the commons. Municipal ordinance might allow special street privilege to a railroad or utility company, to delivery firms, to a semi-permanent street vendor or for a block party’s temporary closure. But the phrase “street privilege” also could be a reminder that the access to the public space of the city has been unevenly allocated; transit through the city has been a privilege unequally shared. A human history of parking could take street privilege seriously, and examine how the mundane and everyday inequalities of urban space shaped urban mobilities and transit.

James Longhurst is Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, and the author of Bike Battles: A History of Sharing the American Road (University of Washington Press, 2015), in translation as Las Batallas de la Bici (Katakrak, 2019).

James Longhurst is Professor of History at the University of Wisconsin-La Crosse, and the author of Bike Battles: A History of Sharing the American Road (University of Washington Press, 2015), in translation as Las Batallas de la Bici (Katakrak, 2019).

Featured image (at top): An undated photo of an unidentified woman, perhaps from Columbia, South Carolina — either a policewoman or a parking attendant; a “meter maid.” From the John Henry McCray papers, 1929-1989, University of South Carolina, South Caroliniana Library.

[1] Robert D. Mcfadden, “A Meter Maid and an Officer Trip Over Law,” New York Times (Feb 2, 1979), B3.

[2] Genevieve Carpio, Collisions at the Crossroads: How Place and Mobility Make Race (University of California Press, 2019), 3.

[3] “The Infrastructure of Movement: Moving the City, An Overview and Bibliography for Urban Transit History,” https://themetropole.blog/2020/04/02/the-infrastructure-of-movement-moving-the-city-an-overview-and-bibliography-for-urban-transit-history/

[4] Julianne McShane, “Bicycle Diaries: Two Centuries of New York City History,” New York Times (May 23, 2019). https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/23/arts/design/bicycle-exhibition-museum-of-the-city-of-new-york.html

[5] Sarah A. Seo, Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed American Freedom, Harvard University Press, 2019; Carpio, Collisions at the Crossroads.

[6] John Jakle and Keith Sculle, Lots of Parking: Land Use in a Car Culture, Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2005; Kerry Segrave, Parking Cars in America, 1910–1945: A History, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2012. For the urban design view, see Eran Ben-Joseph, Rethinking A Lot: The Design and Culture of Parking, MIT Press, 2012; for a useful legal philosophy, Sarah Marusek, Politics of Parking: Rights, Identity, and Property, Routledge, 2012.

[7] Some historians have examined the human history of parking, including multiple publications by Virginia Scharff, like “Of Parking Spaces and Women’s Places: The Los Angeles Parking Ban of 1920,” NWSA Journal, 1:1 (Autumn, 1988), pp. 37-51, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4315865. There is also a great deal of more theoretical work, like Peter Merriman’s “Mobility Infrastructures: Modern Visions, Affective Environments and the Problem of Car Parking,” Mobilities 11:1, (February, 2016), 83-98.

[8] Some of this was previously presented in brief overview at the “Maintainers III: Practice, Policy and Care” conference in Washington, D.C., October 6-9, 2019.

[9] James Longhurst, Bike Battles: A History of Sharing the American Road, (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2015), 229-232.

[10] Cohen v. Mayor 113 N.Y. 532–535 (1889), quoted in Longhurst, Bike Battles, 89-90.

[11] For more on the storage needs of the horse-powered city, see Clay McShane and Joel A. Tarr, The Horse in the City: Living Machines in the Nineteenth Century (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins, 2007), chapter 5.

[12] Peter D. Norton, Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City, (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), 21-64.

[13] Eric H. Monkkonen, “History of Urban Police,” Crime and Justice 15, (1992), pp. 547-580, especially 556-60; quote from 557. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1147625. For more recent work in this vein, see Robert E. Worden and Sarah J. McLean, Mirage of Police Reform: Procedural Justice and Police Legitimacy (University of California Press, 2017), 14-41; Stephen D. Mastrofski and James J. Willis, “Police Organization Continuity and Change: Into the Twenty‐first Century,” Crime and Justice 39:1 (2010), 55-144. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/653046

[14] Sarah A. Seo, “The Fourth Amendment, Cars, and Freedom in Twentieth-Century America,” (Princeton: Ph.D. Dissertation, 2016), 14.

[15] “’Meter-Maid’ Bill Gains Approval: Estimate Board Unanimous,” New York Times (August 21, 1959), 23.

[16] Walter B. Douglas, “Driver Held In Tiff With Meter Maid,” Washington Post, (December 2, 1961), D1.

[17] “Trouble Adds Up Over ‘Meter Maid,’” Washington Post, (Jan 10, 1962), A3.

[18] “Court Reverses Conviction In Heckling of Meter Maid,” New York Times, (September 26, 1962), 34.

[19] “Meter Maid Pays $10 Traffic Fines: Found Guilty Of 2 Violations,” New York Times Sept 7, 1960; pg. 43

[20] Quotes from “N.Y. Meter Maid Nails 2 Police,” Washington Post, (September 14, 1972), E4; see also “Meter Maid Arrested; Ticketed a Police Car,” New York Times (September 13, 1972), 49.

[21] Joseph P. Fried, “Arrest of Meter Maid Fosters Murphy-Karagheuzoff Dispute,” New York Times (September 14, 1972), 51.

[22] Robert D. Mcfadden, “A Meter Maid And an Officer Trip Over Law,” New York Times (Feb 2, 1979), B3.

[23] “Philadelphia meter maids . . . ,” May 21, 1980. Jack Tinney photograph, George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection, Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. P703005B https://digital.library.temple.edu/digital/collection/p15037coll3/id/41742/rec/1

[24] For an introduction to the wide-ranging impacts of parking policy on cities, see Donald Shoup, The High Cost of Free Parking, American Planning Association, 2011; Donald Shoup, ed., Parking and the City, Routledge, 2018.