By Philip Mark Plotch

New York City’s subway system, once the best in the world, is now frequently unreliable, uncomfortable, and overcrowded (at least when the city is not experiencing a pandemic). One of the reasons for its sorry state is a series of uninformed and self-serving elected officials who have fostered false expectations about the city’s ability to adequately maintain and significantly expand its transit system. That began more than a century ago with a mayor named John Hylan.

The subways and elevated rail lines enabled New York to expand outward because they cut commuting times. Likewise, the city could grow upward because trains carried enough workers and visitors to make skyscrapers financially feasible. Before the elevated lines were built, Trinity Church in Lower Manhattan was the city’s tallest building. In 1913, nine years after the first subway line opened, the first office workers moved into the 57-story Woolworth Building.

In a 1920 visitors’ guide to New York, Henry Collins Brown wrote, “The subway will take you within a few blocks of anywhere, and the fare is only a few cents, even if you ride to the end of its fifteen miles. There is no city in the world where transportation is so good, and between ten and four the cars are not uncomfortably crowded.” He also offered a tip about the locals: “Don’t gape at women smoking cigarettes in restaurants. They are harmless and respectable.”

When the private railroad companies that built the subway lines first began service, they expected to reap enormous profits, a portion of which they would share with the city. But their contracts with the city contained one provision that would affect the transit system’s financial viability and the potential for further expansion: the fare had to be kept at five cents per trip for the duration of their 49-year lease agreements.

New York has long regulated the fees that privately owned monopolies, like the early 20th-century railroads, were allowed to charge customers. For example, utility companies could not raise their electric rates without approval from the state. The regulators knew that limiting rate hikes might be politically popular, but if the companies did not have sufficient revenues, they would not be able to properly maintain their equipment and expand their electricity-generating capacity.

In the early twentieth century, however, New York’s politicians took a shortsighted approach to the transit system. Instead of allowing the firms to raise fares, the elected officials raised false expectations that New Yorkers could have high-quality subway service with low fares. The repercussions would last for generations.

The financial health of the private railroads deteriorated after the first lines were extended and new ones built. Although passengers traveled longer distances, the railroads could not recoup their increased operating expenses by charging higher fares. Moreover, in the 20th century’s second decade, automobile use soared and inflation surged. To deal with their red ink, the railroads cut staff, reduced salaries, deferred investments, and cut back on station and train cleaning. As a result of their cost-cutting moves, service became less reliable and the system began to deteriorate.

New York mayors promised that if the city took over the private railroads, a city agency would provide better subway service at lower costs. They also promised to build new rail lines all across the city. New York’s mayor, John Hylan, even said that the city would earn a profit on the nickel fare that could be used to fund new schools, parks, and highways.

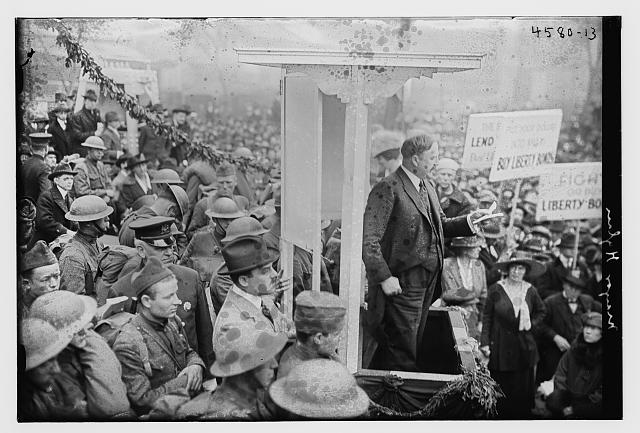

As mayor, Hylan made mass transit his leading issue and referred to the companies that operated the subways as “greedy, power-mad behemoths that double-crossed the public at every turn.” One of the railroad heads accused Hylan of ruining the transit system and using it as a “political escalator.” Mayor Hylan considered the nickel fare “as sacred and binding as any contracts ever drawn in the history of financial transactions the world over.” With the fare as the centerpiece of his 1921 reelection campaign, Hylan trounced his Republican, Socialist, Labor, and Prohibition Party opponents, winning more than 64 percent of the vote.

The city did purchase the private railroads in 1940, but because elected officials were loathe to raise the fare and operate the system efficiently, the subways never obtained enough resources for proper maintenance. That is why in the early 1950s, only about 10 percent of the subway cars were modern and up-to-date.

New York’s transit system has rebounded from its worst period, when one-third of all the subway cars pulling into stations had broken doors and a subway car caught fire nearly seven times a day. But, the basic problem has not changed. The public and many elected officials still demand improvements and new subways lines without understanding how expensive they are.

Workers could build urban railroads remarkably fast and relatively inexpensively before today’s building, environmental, and labor regulations were instituted. Now, planning and construction periods take decades rather than years. In the 1870s, the 28 elevated railroad stations built above Second Avenue El were completed in less than two years. By comparison, the three new subway stations below Second Avenue opened in 2017, more than 88 years after they were first promised. Even after taking inflation into account, the cost per station to build the Second Avenue subway stations was 25 times higher than the subway’s construction cost in the early 20th century when workers used pickaxes, not tunnel-boring machines.

Elected officials are still loathe to raise sufficient revenues for maintaining the subway system. Likewise, they are unable and unwilling to reduce some of the transit system’s excessive costs. As a result, New York’s transportation authority has taken on more debt than dozens of U.S. states and its infrastructure is woefully inadequate. Not only are the stations and train cars desperately in need of modernization, so too are the 80-year old signals that keep trains from crashing, the aging pumps that protect equipment from getting flooded, and the ventilation systems that are supposed to prevent smoke from asphyxiating riders in case of an emergency.

Beware of politicians who promise that they can upgrade and expand their transit systems and provide reliable service without asking you to pay more.

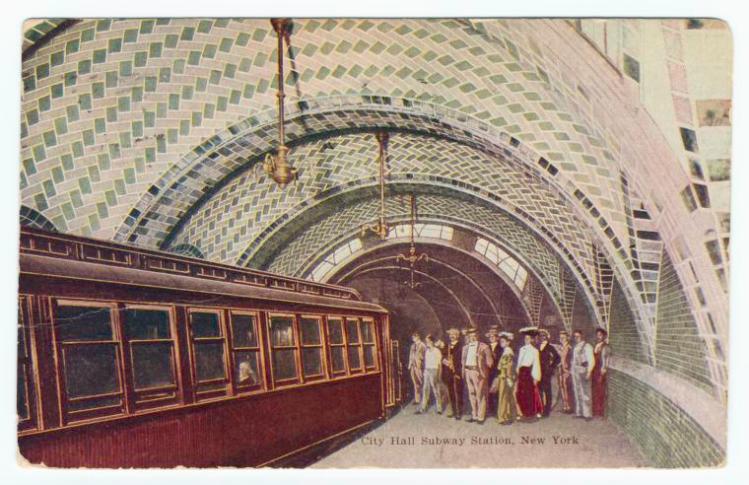

Featured image (at top): City Hall Subway, New York City, postcard 1906, Historical Postcards of New York City, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints, and Photographs, New York Public Library.

Material drawn from Chapter 2, “An Empty Promise,” in Last Subway: The Long Wait for the Next Train in New York City, by Philip Mark Plotch. Copyright (c) 2020 by Cornell University. Used by permission of the publisher, Cornell University Press. All rights reserved.

Plotch is an associate professor and director of the Master of Public Administration program at Saint Peter’s University in New Jersey. He is the author of the new book, Last Subway: The Long Wait for the Next Train in New York City.