By Richard Harris, McMaster University

I enjoyed Victoria Wolcott’s recent item in The Metropole. Engaging, and deeply-felt, it effectively made the point that the lives and struggles of black women are among the most neglected aspects of the American urban experience. But one phrase gave me pause. She suggested that lately we have been “neglecting cultural history.” That may well be true. But her comment triggered the thought that there is a more substantial and long-standing gap in our scholarship: the urban economy.

Surely no one would claim that this is an unimportant subject, but who is studying it? Urban settlements of all sizes play a vital role as trade and financial hubs, as centers of manufacturing, and as places of consumption. We know that. But if we want to understand why cities thrive, or decay, we need to know what sorts of advantages they offer to the various types of businesses that create jobs and make things hum. Economists and economic geographers talk about economies of scale and of agglomeration: the advantages of having access to public infrastructure, to pools of labor, and suppliers of materials and business services, including specialized legal, financial, and marketing skills. More generally, if we care about national economic growth, we need to know what role urbanization has played, in part through those economies and also through the innovations that, so we are often told, depend on the face-to-face contacts and ‘buzz’ that cities foster.

Over the decades, a number of leading scholars have argued the need to know more about the economic history of cities, and many have demonstrated the case. They have included economic historians such as Norman Gras, Bert Hoselitz, Eric Lampard, Lionel Frost, Richard Goldthwaite, Jan de Vries, Paul Hohenberg, and Paul Bairoch, historical geographers such as Ted Mueller, Gordon Winder, and Robert Lewis, and urban historians with broad interests such as Ray Mohl, Richard Rodger, and Bob Morris. But their examples, and their urgings, have had much less influence than they should. I’m not sure why, but I do think it’s a great pity.

As it begins to loom on our mental horizon, Detroit dramatizes this gap in our knowledge as well as any city can. It has been the subject of a number of fine works by urban historians, including Olivier Zunz, Tom Sugrue, David Freund, Heather Barrow, Sarah Jo Peterson, Victoria Wolcott herself and, most recently, Rebecca Kinney and Kimberley Kinder. These writers have explored the policy context, as well as the political, social, and geographical dimensions, of growth and (especially) decline. Between them, Heather Barrow and Sarah Jo Peterson have told us something about Henry Ford’s operations, both for his own company and on behalf of the federal war effort. But what no one has attempted is to track the internal dynamics of the city’s business operations: the network of agglomeration economies, the disparate forms and sources of innovation, how they dried up and, in general, the role that geography of the metropolitan area and region – extending to Ypsilanti and Flint – played in all of this.

What a pity! Detroit is a textbook case of industrial growth and decline, of the dangers of industrial specialization, and of struggling rebirth. Lately, it has illustrated the effects of what Neil Smith called the rent gap, but on an industrial scale. Taking advantage of abundant cheap real estate, Dan Gilbert’s Quicken Loans has made the city’s Central Business District into a sort of modern company town, owning property of all kinds and functioning in many ways as a self-contained entity; locals speak of ‘Gilbertville.’ Over the course of a century, then, Detroit has offered enormous potential for exploring the industrial dynamics of growth, decline, and rebirth. Who will tell that story? There is a great opportunity here for a junior scholar to make a mark.

Past president of the UHA (2017-18), Richard Harris teaches urban geography at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario. He has written several accounts of Toronto’s suburban development, notably Unplanned Suburbs. Toronto’s American Tragedy, 1900-1950. (Baltimore, 1996).

Past president of the UHA (2017-18), Richard Harris teaches urban geography at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario. He has written several accounts of Toronto’s suburban development, notably Unplanned Suburbs. Toronto’s American Tragedy, 1900-1950. (Baltimore, 1996).

This post contains affiliate links. If you end up making a purchase, we may earn a commission on the sale. Thank you for supporting the hard work of writers and editors.

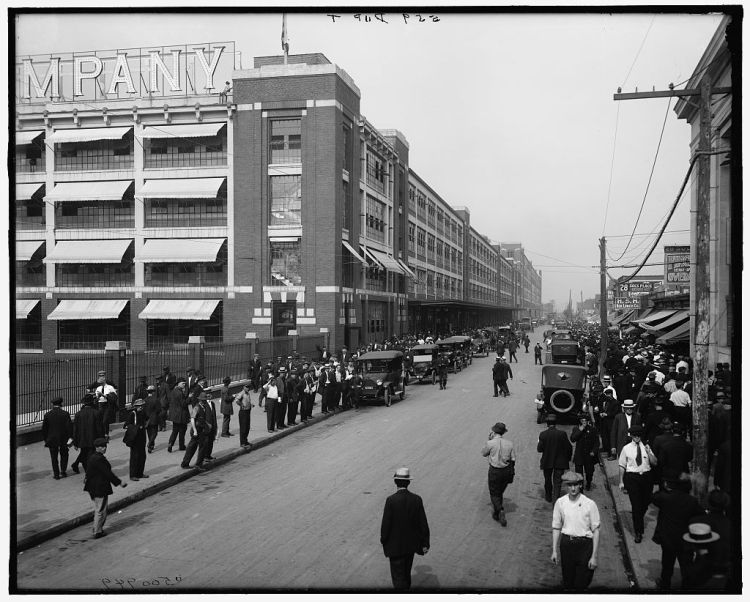

Featured Image: Four o’clock shift, Ford Motor Company, Detroit, Mich., Detroit Publishing Co. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

In her book “Economy of Cities” (published in 1969), Jane Jacobs addresses this very point. In her book “Cities and the wealth of Nations” (published in 1985), she gives a more broad view on the roll of cities in our economy.

LikeLike