By Daniel Clark

For most of the twentieth century, autoworkers and their families were a large share of metro-Detroit’s population, and the decade and a half after World War II has been widely considered to be their heyday. Those familiar with the literature on Detroit history will immediately, and correctly, point out that Tom Sugrue’s 1996 Origins of the Urban Crisis undercuts the argument that the 1950s was a golden age for the city, especially for its African American workers. Sugrue argues that black autoworkers suffered disproportionately from job losses due to automation and decentralization of the industry away from Detroit and encountered persistent discrimination and violence in the quest for housing. The city’s decline started in this period, not in the late 1960s.[1]

Nevertheless, a consensus has developed that during the 1950s, with help from lucrative union contracts, autoworkers enjoyed a decade of job stability and economic advancement as they rode the postwar boom into the middle-class. According to this view, real wages doubled between 1947 and 1960 and autoworkers received new fringe benefits like pensions and company-paid health insurance. Some historians have seen these material gains as lamentable, fostering complacency and undercutting militancy, while others considered them to be a monumental achievement. But both schools of thought agreed that autoworkers, for the most part, experienced prosperity during these years. It’s even possible to infer from Origins that this was true for white autoworkers, who received favorable treatment at hiring gates and could move beyond the city to follow jobs to their new destinations. Today, with the decline of unionization rates and the vast expansion of income equality, labor historians tend to look back more fondly than in the past regarding the relative power the UAW wielded in the postwar era. Indeed, in recent years historians from across the political spectrum have reinforced the argument that the early postwar period was a golden age for autoworkers, an exception from the instability and relative powerlessness that bookended it.[2]

Most of the historical literature on autoworkers, however, focuses on their union, the United Auto Workers, and its longtime president, Walter Reuther, which inspired me to launch an oral history project to explore how ordinary workers experienced the 1950s. Based on the existing literature, I fully expected to hear stories, at least from white workers, about living in an era of increasing prosperity.

Instead, a contrasting pattern emerged after more than forty interviews. Hardly anyone, male or female, white or African American, recalled the 1950s as a time of secure employment, rising wages, and improved benefits. Although most of these interviewees tried to be autoworkers throughout the 1950s, layoffs were so frequent that in many cases they actually were autoworkers only about half the time. All of them had secondary support systems, often including unemployment benefits, but more frequently involving alternative jobs. A partial list of the positions held during these years by interviewees includes: trailer home washer, cab driver, department store clerk, bank employee, telephone pole installer, promotional event searchlight operator, feed store worker, cyclone fence installer, moving company worker, University of Michigan Law Club janitor, junior high cafeteria worker, insurance repair construction worker, winery employee, trash hauler, chicken farmer, wallpaperer, Army surplus store employee, barber, berry picker, cotton picker, golf caddy, and soldier. It wasn’t clear that the category of “autoworker” had any consistent meaning.

But did this interview evidence mean anything? Had I just discovered a few dozen outliers, individuals who couldn’t succeed in an era of abundance? Almost everyone I interviewed had been quite young, in their 20s or 30s, during the 1950s—and many 1950s autoworkers were much older than that. How could I determine whether or not my interviewees’ experiences were at all representative? It seemed to me that conducting even a hundred or two hundred more interviews, even a thousand more, would lead to the same impasse over representativeness. And it takes a long time to transcribe interviews. I wanted to finish this project before I died, or at least before I retired. Instead, I read Detroit newspapers—two daily papers, the Detroit Free Press and the Detroit News, and the Michigan Chronicle, an African-American weekly based in Detroit—to see if they would corroborate or contradict the oral evidence.

The newspaper evidence overwhelmingly supported and enhanced what interviewees had recalled. The auto industry in no way provided stable employment and secure, rising incomes. Everybody knew it, from recent production-line hires to the presidents of the Big Three. African-American workers had it worse than whites, to be sure, but auto work was unstable and insecure for just about everybody, in the city and in the suburbs. In only three periods during the 1950s—in 1950, 1953, and 1955—were there several consecutive months of sustained full employment. Most hiring occurred during these brief upsurges, especially in 1953, and these new employees were an increasingly large proportion of all autoworkers. Many of those I interviewed decades later were part of the 1953 hiring boom, so it turns out that my sample was more representative than I imagined.

For my research purposes, “Detroit” meant, in addition to the city itself, Wayne County and parts of neighboring Macomb and Oakland counties. That was the definition of Detroit used by state agencies for calculating unemployment statistics, in part because it allowed inclusion of huge plants like the Ford Rouge, technically in Dearborn, the Dodge Main, officially in Hamtramck, and Pontiac Motor, in Pontiac.

Immediately after the war, instability was largely the result of materials shortages. There was a postwar boom, but it required a lot of steel, and the auto industry was one of many hoping to gain access to supplies. In addition, strikes by steelworkers and coal miners interrupted auto manufacturing, sometimes for weeks at a time, as did walkouts by copper and glass workers. Strikes in the auto industry, including at any of the thousands of parts suppliers, disrupted employment up and down production networks. Industrial workers across the country were trying to keep pace with inflation and to hash out local issues of concern to them, but the impact on the auto industry was severe, which meant frequent layoffs for autoworkers.

Layoffs hurt workers much more than auto companies. Unemployment compensation helped, paying $20 a week plus $2 a week per child for up to four children (the average UAW hourly wage at the time was about $1.30, roughly equivalent to $17 in 2019). But workers with less than a year of seniority or who had interrupted job histories did not qualify for unemployment benefits. Many laid-off autoworkers traveled to stay with relatives, often in West Virginia, Kentucky, Arkansas, or northern Michigan. Most of those who stayed in Detroit tried to find odd jobs, like those mentioned above. Corner grocery stores extended credit when possible and workers’ medical bills went unpaid, along with rent, mortgage payments, insurance premiums, and utility bills. Automakers would have preferred steady production, but with a few exceptions for Chrysler, they posted solid profits each year despite frequent interruptions.

The notion that there was a postwar boom for autoworkers rests largely on the significance of contracts signed in 1950 between the UAW and automakers, especially the one with GM, which Fortune magazine called The Treaty of Detroit. These contracts provided for hefty wage increases, cost-of-living allowances, raises linked to productivity gains, pensions, and improved health insurance. Historians have disagreed about whether this was a positive or negative development, but almost everybody has accepted that the contracts accomplished what they said they would do. But Chrysler’s 1950 contract came after a 104-day strike that left nearly 100,000 autoworkers in a state of desperation. When the strike was won, Frank Lubinski, who never wavered in his support of the walkout, remarked, “I don’t think we have too much to celebrate. I can’t forget the bank note for $285, the payments on the washing machine, the doctor bill, the three light bills, three gas bills, three telephone bills and four house payments.” Soon after major automakers and suppliers had signed their contracts, war in Korea broke out. This resulted in a brief surge in auto sales and production, as people feared a repeat of WWII’s rationing. Then actual materials rationing kicked in. Steel, aluminum, and copper shortages undercut auto production for the next two years. The situation became so dire in Detroit that automakers, union leaders, and city officials distributed a flyer around the country in January 1951 that stated: “Attention would-be war workers! Stay away from Detroit unless you have definite promise of a job in this city. If you expect a good-paying job in one of the big auto plants at this time, you’re doomed to disappointment and hardship.” For the next two years there were always over 100,000 unemployed Detroiters, most of them autoworkers, with the official total reaching 250,000 in August 1952. At one point in 1952, 10 percent of all the unemployment in the nation was concentrated in Detroit. Moreover, you were counted as “employed” if you worked as little as one hour per week. Underemployment was a chronic problem that remained invisible in official unemployment statistics. Again, this was all after those lucrative 1950 contracts were signed. The wages and benefits written into those agreements gave a misleading impression of how autoworkers actually lived.

There were exceptions, as mini-booms boosted the economy. The federal government lifted Korean War materials restrictions in late 1952 and early 1953 and autoworkers benefited for several months from high levels of production and steady employment. Suddenly automakers were recruiting far and wide for new workers, including everywhere the dire warnings against coming to Detroit were distributed a couple of years earlier. Recruitment proved difficult, however, because of the industry’s instability, which, according to one report was “so well recognized that potential workers know that today’s hiring boom can become tomorrow’s layoffs.”

Sure enough, the production boom saturated the market by mid-1953 and the auto industry suffered more than most other sectors of the economy during the 1954 recession. A Detroit News editorial offered its perspective: “It is a fact, however unfortunate, that the industry . . . has had need of a labor force that is readily expandable and contractile, and this need to a degree has been accommodated by the working habits of Detroit families.” Desperation, however, not easy accommodation, was apparent outside unemployment offices. Also, the independent automakers that once flourished in Detroit, like Hudson, Packard, and Kaiser-Frazer, merged with other independents, Nash, Studebaker, and Willys-Overland, and the net result was the loss of tens of thousands more auto jobs in Detroit.

By their own admission, automakers had relented a bit in early 1953 on hiring African American men, white women, the elderly (i.e. over 40), and those with disabilities, but discrimination kicked in with full force when times got tough. Automakers and city officials complained about the number of unemployed autoworkers in Detroit and called for those who arrived during boom times to leave the area, and the auto industry, for good. Automakers and civic boosters blamed autoworkers for the industry’s tough times. Their high wages, the argument went, boosted the price of new cars and limited sales.

But contrary to conventional wisdom, few autoworkers earned enough to purchase new cars. Those that did often had them repossessed during layoffs. These were the elites of unionized, industrial workers in the country, but unless they were single, childless, and sharing the rent, they were priced out of the market for new cars even when fully employed. That was especially true for workers with large families, and this was the baby boom. As GM put it, these blue-collar customers could drive used cars. Still, for many autoworkers, given employment instability, even a used-car purchase was a dicey proposition. Automakers targeted the nation’s top 14% of income earners for the new car market, which meant that a huge chunk of Americans, pretty much the entire working class, were not prospective new car buyers.

Conditions improved in 1955, when automakers made record profits and produced more than nine million vehicles, the largest annual output of the decade. Workers enjoyed steady employment, at least during the first half of the year. Yet those on the job worried that the good times might not last. “We are working from nine to 12 hours a day. We don’t mind the extra loot as we have lots of fun spending it,” admitted Jim Basden of UAW Local 212. “But I shudder to think what is going to happen later on. A saturation point is inevitable.” Indeed, demand did not keep pace with production, and at year’s end almost a million vehicles sat unsold on dealers’ lots across the country. Auto production was accordingly scaled back, with accompanying layoffs.

The peak years for the U.S. economy as a whole during the decade were 1956 and 1957, but those were dismal times for autoworkers in Detroit. Again, aggregate economic data and contract provisions did not provide an accurate sense of autoworkers’ experiences. Overall unemployment in Detroit was consistently over 100,000 in these years, or about 7 percent, but industrial unemployment was generally double that rate. Short workweeks were common. According to the U.S. Department of Commerce,1957 surpassed 1956 to become America’s newest “best year ever.” In contrast, according to the Michigan Employment Security Commission (MESC) 1957 in Detroit was marked by “continuing serious unemployment, high payment of jobless benefits and concurrent reduction of manufacturing employment to the lowest point since 1949.” This was true despite the auto industry recording its fourth-best annual output ever. Even skilled workers, the elite of the supposed elite, and all white by virtue of racial barriers to apprenticeships, were upset in the 1950s. They suffered from wage compression, making their apprenticeships less valuable, and unemployment among skilled workers increased, something that wasn’t supposed to happen. By the end of 1957, Detroit’s auto industry had laid off two-thirds of its skilled workers.

In April 1958, when unemployment in Detroit reached 17 percent—over 265,000 people—during a national recession, Benson Ford, the younger brother of Henry Ford II, remarked, “There is no other business with anything like the same elements of risk, big stakes, feverish competition, ecstatic highs and gloomy lows.” For autoworkers, 1958 was a gloomy low. Throughout the year, according to the MESC, “the job picture was grim.” “I don’t think I’ve had three solid month’s work all year,” said Dodge Main employee Robert Weatherburn, age 50, just before Christmas. Unemployment levels remained staggeringly high—nearly 250,000 Detroiters, or roughly 16 percent of the area’s work force—in late March 1959. In hindsight, economists and historians have considered this recession to be a minor nuisance in a prosperous era. It was anything but to those who lived through it.. As one report described the situation in 1960, Detroit’s economy was “a baffling conglomerate of millions of sales, paychecks and layoffs . . . What IS happening? Which way ARE we headed?”

In April 1958, when unemployment in Detroit reached 17 percent—over 265,000 people—during a national recession, Benson Ford, the younger brother of Henry Ford II, remarked, “There is no other business with anything like the same elements of risk, big stakes, feverish competition, ecstatic highs and gloomy lows.” For autoworkers, 1958 was a gloomy low. Throughout the year, according to the MESC, “the job picture was grim.” “I don’t think I’ve had three solid month’s work all year,” said Dodge Main employee Robert Weatherburn, age 50, just before Christmas. Unemployment levels remained staggeringly high—nearly 250,000 Detroiters, or roughly 16 percent of the area’s work force—in late March 1959. In hindsight, economists and historians have considered this recession to be a minor nuisance in a prosperous era. It was anything but to those who lived through it.. As one report described the situation in 1960, Detroit’s economy was “a baffling conglomerate of millions of sales, paychecks and layoffs . . . What IS happening? Which way ARE we headed?”

Local leaders were perplexed because the elite downtown area of Detroit continued to thrive. Shopping remained intense at pricey department stores like Hudson’s and aggregate savings among Detroiters indicated that there was plenty of purchasing power in the region. Working-class neighborhoods, however, were devastated, with shuttered storefronts and rampant unemployment. As the Urban History Association hosts its convention in Detroit, members will certainly debate the merits of current development in downtown and midtown and the limits of its impact on huge portions of the city. There might be talk of the city’s heyday, with an understanding that auto manufacturing will never again provide hundreds of thousands of high-paying jobs in the region. But it’s important to be clear about that supposed heyday. Even then, for ordinary autoworkers the so-called postwar boom was marked by job instability and economic insecurity. Everyone from workers themselves to auto executives knew that full-time employment was only temporary. This is lost when focusing on wage rates, fringe benefits, and industry profitability, or on top-level UAW policy and politics.

Daniel Clark is an Associate Professor of History at Oakland University, which is in Rochester, Michigan, about twenty miles north of Detroit. He is the author of Like Night and Day: Unionization in a Southern Mill Town (University of North Carolina Press, 1997) and Disruption in Detroit: Autoworkers and the Elusive Postwar Boom (University of Illinois Press, 2018).

Daniel Clark is an Associate Professor of History at Oakland University, which is in Rochester, Michigan, about twenty miles north of Detroit. He is the author of Like Night and Day: Unionization in a Southern Mill Town (University of North Carolina Press, 1997) and Disruption in Detroit: Autoworkers and the Elusive Postwar Boom (University of Illinois Press, 2018).

This post contains affiliate links. If you end up making a purchase, we may earn a commission on the sale. Thank you for supporting the hard work of writers and editors.

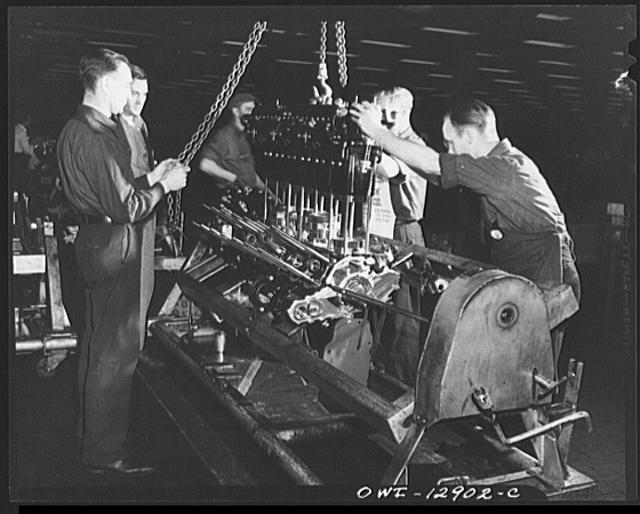

Featured image (at top): Detroit, Michigan. Members of the United Automobile Workers (UAW) of the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) carrying various signs in the Labor Day parade, photograph by Arthur S. Siegel, September 1942, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

[1] Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996).

[2] Nelson Lichtenstein’s The Most Dangerous Man in Detroit: Walter Reuther and the Fate of American Labor (New York: Basic Books, 1995) is largely critical of these developments, while John Barnard’s American Vanguard: The United Auto Workers during the Reuther Years, 1935-1970 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004) takes a more positive view of the same evidence. Jefferson Cowie, The Great Exception: The New Deal and the Limits of American Politics (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016); Robert J. Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living since the Civil War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016); and Marc Levinson, An Extraordinary Time: The End of the Postwar Boom and the Return of the Ordinary Economy (New York: Basic Books, 2016) all emphasize that the early postwar years were a heyday for autoworkers.