It’s the final installment of Digital Summer School 2019! Wayne State’s Jennifer Hart drops us into the transit grid of Accra, Ghana as she and others working on the Accra Wala project engage the city’s public transportation system and the broader concept of automobility. For all other DSS 2019 courses scroll down to the bottom for links.

Accra Wala emerged from not only your own research on automobility in Ghana and elsewhere, but also due to the fact that you felt this scholarship and other work like it often does not reach the public, especially the general population in places like Ghana. What is Accra Wala and how will it bridge the divide between academic and popular knowledge?

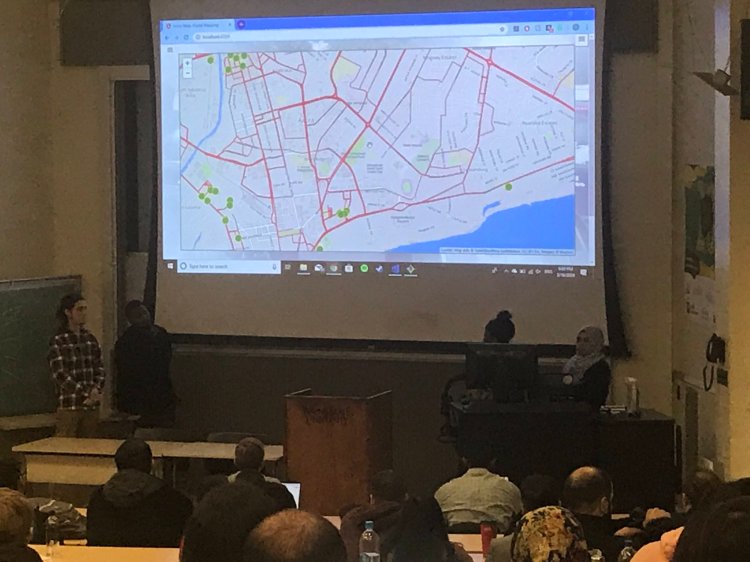

Accra Wala is an interactive online map of the trotro (or public transport) system in Accra, Ghana. The map of the trotro system’s routes, bus stops, and lorry parks serves as the base for a publicly-generated, place-based archive. Users will be able to use the platform to post geotagged photos, video, or audio clips that document life in the city. They can post media at individual nodes, which are connected to the city’s major lorry parks (or bus stations), but individuals can also work with us to research and submit “itineraries” that take users on a journey through the city by telling place-based stories that connect multiple nodes. Itineraries and media can be contemporary or historical (with appropriate citation, of course!), and it does not have to deal with the experience of transportation directly. The trotro system spatially anchors the story and provides some organizational coherence to the project, but it also pushes us to think differently about how people move within city space.

Trotros are the most widely used form of transportation in Accra, and yet their network is rarely if ever represented on maps of the city. We miss something fundamental about urban life if we are not fully taking into account how and where people move. But also, mobility systems tell us something about the way that people interact with and organize space – how they transform space into place.

Today, in cities like Accra, these systems are often labeled as “informal” and are the subject of both public and state hand-wringing, complaints, and criminalization. And yet, the history of trotros and other forms of “informality” in cities like Accra often force us to reconsider these contemporary narratives. In the context of colonialism, grassroots strategies like the trotro reflected an attempt by African urban residents to make the city “work” for them and create the infrastructural networks that African residents needed but that either colonial officials did not provide or that were otherwise insufficient. We might think of trotros as automobile desire lines. Colonial governments created infrastructure that sought to change the behavior of African residents and furthered the interests and priorities of the colonial state, rather than creating infrastructure that truly represented the public interest. Roads in Accra were not built to facilitate African urban life, but African residents re-appropriated and redefined those roads in new ways that facilitated aspirational and entrepreneurial goals.

As my book argues, Africans dominated the motor transport system much earlier than was possible in other parts of the continent in large part because African farmers and traders controlled cash crop production (particularly of cocoa), and, as early as the 1910s, farmers and traders used those profits to invest in wooden-sided trucks, often referred to as “mammy trucks” due to their association with the female market traders who used them to travel long distances and engage in wholesale trade. By the 1930s, mammy truck drivers began picking traders up and transporting them throughout the city. British colonial officials engaged in a lot of hand-wringing over these vehicles, which they condemned as “pirate passenger lorries.” The persistence of drivers and passengers in creating a system that reflects their needs is a powerful one, and yet it is a story that is little-known.

The Accra Wala project grew out of requests from drivers and passengers that I create a map of the trotro system. The system can be difficult for outsiders (or even insiders) to navigate, so a map is helpful in that regard. But there’s also something about the capacity of mapping to make systems visible, and thus more permanent or legitimate or formal. The bulk of the research for my book, during which I spent a lot of time in lorry parks interviewing drivers, coincided with early discussions about a Bus Rapid Transit system. The official line in those planning discussions was that trotros were problematic, unruly, and disorganized, and drivers felt particularly aggrieved about that. These statements are not true, they pointed out – trotro drivers were organized into unions that operated out of lorry parks and maintained relative order, and while the vehicle and training standards may have declined over the years that says as much about broader economic conditions as it does about changing driver practices. Those kinds of statements also don’t reflect the reality that trotros carry 85% of the city’s mobile residents while accounting for only 15% of road traffic. So, Accra Wala is part of a broader movement to make these systems visible. Other projects like Digital Matatus or the Accra Mobile project have also been doing this work to different, policy-driven ends, producing maps that make it easier to navigate through and track these systems.

But Accra Wala also aims to move beyond the act of mapping itself. In particular, I saw this as an opportunity to translate some of the academic conversations happening around issues of mobility and urban development for public audiences and create new opportunities for the public to shape the way the city was labeled, organized, and discussed. My book provides a lot of this context, but it is not easily available in Ghana. And while I sometimes do write on a publicly-accessible blog and in other public forums like Africa Is A Country, that still limits the voices and perspectives presented. I am often asked what kinds of research or analysis or conclusions I wish to generate out of this project, and I guess my answer is that I don’t know. Not that I don’t have some hypotheses – I think it’s possible (depending on who ultimately contributes to the site and how widely it’s picked up) that we might be able to visualize urban social, cultural, and economic networks in new ways or, rather, spatialize practices that we know exist but have not really been mapped. That might show, as many scholars have argued, that what we often see as the chaos of the “informal” is actually quite systematic and organized. That is potentially quite powerful and important for scholars, policy-makers, and citizens alike. But I’m also prepared to be surprised by what the site generates, and I want to remain open to partnerships and opportunities that might take it in otherwise unexpected directions. I’m really interested in continuing to partner with Open Street Maps Ghana to do community mapping, for example.

How do you envision the public, students, and teachers, whether at the college, secondary, or elementary school level, engaging with and using Accra Wala?

The media submission opportunities and archives of the site are completely open to the public. Educators or non-profits might have kids collect media examples and upload them to the site as part of the project. Instructors might have students use the archive as a resource for research projects. I think these sorts of opportunities are exciting for students at all levels because their name is attached to their work and it is seen by a much broader audience – not just something that is turned in for a grade and seen by their teachers and family. Graduate students and researchers are welcome to use the site to spatialize some of their own research or translate it for a public audience. Artists or entrepreneurs might use the site as a way to envision the work that they do or the networks in which they are involved. There are a wide range of possibilities, and I’ve been working with students at Wayne State and Ashesi University to begin that work. We’ll be continuing to do that in summer 2020.

In submitting media, people help to build out the site as a popular archive of city life. That’s important and interesting in and of itself. However, I am particularly excited about the possibilities of the itineraries. Because itineraries are more involved and require more active and intentional storytelling, we ask people who are interested in creating itineraries to work directly with us. That could happen on an individual level, but it could also happen through classroom work. I am very excited about the prospect of classroom instructors having students research and write itineraries as a part of a class project. Those itineraries can be contemporary or historical, so for history instructors this creates an alternative way to engage with archival sources and the crafting of historical narratives. Asking students to do work “in public” can be difficult, but I think it is often also rewarding for them and for us. I’m also positive that people will come up with ideas for how to engage with the site that I have not thought about before, so I want to remain as open as possible to those opportunities! There is a degree to which I control the site by creating the platform and serving as a site administrator, but I truly do want it to take on a life of its own.

What about automobility makes it useful for thinking about Ghana, Africa, and other parts of the world?

Automobility – particularly for Americans – carries with it all sorts of assumptions about physical infrastructure and the cultures, socialities, and economies of movement. We associate automobility with the single-family car and the freedom of the open road, but as I argued in my book, that has not necessarily been the case in Ghana. The relative autonomy and mechanized mobility that the automobile provided for both drivers and passengers did create new kinds of social, cultural, and economic possibilities for Africans in 20th century Ghana. But, if we take that autonomy seriously, we’re also forced to confront the limits of technological determinism. The automobile itself and the road infrastructures that are built to serve automobile citizens are technologies that gain their meaning through use – an idea that Africanist historians of technology have really been exploring over the last ten or so years.

When we take a technological object like the automobile not as an end in itself with predetermined outcomes but rather as a generator of new possibilities that take shape in particular cultural, social, economic, and political contexts, we open entirely new kinds of avenues for scholars and raise questions about the sort of technological imperialism that often accompanied colonial rule. In other words, histories that take seriously indigenous automobile cultures and practices necessarily require us to look at technology through a decolonial lens – to not assume the values attached to technology that we inherit from imperial historical narratives and to imagine new possibilities and alternative futures.

In Ghana and throughout the Global South, this is critically important work for our understandings of the past. But it also informs ongoing processes and practices of development across the continent, which are often guided (intentionally or not) by the same kinds of logics that undergirded the imperial project. As an advocate for all forms of scholarly communication and public engagement, I love that historians are embracing public-facing scholarship and applied scholarship not only to provide context for contemporary action but to also challenge the very parameters or precepts of contemporary debates and raise new possibilities for creating more just systems. This project is in many ways an extension of that work.

More than any Digital Summer School project that The Metropole has highlighted, Accra Wala has required a distinctly transnational approach in the institutions it has engaged, the numerous individuals working in different countries, and the varying agencies and schools that have contributed to the project. What are the benefits of this sort of collaboration and what pitfalls does one need to guard against?

In developing this project, I have intentionally engaged with partners in Ghana at all stages of the process. In part, that is a reflection of the origins of the project – that it developed out of requests from drivers and passengers. Making sure that they remain involved in the project is very important to me. But also, as a historian of Africa, I try to remain aware of the politics of knowledge production and the often-exclusionary history of African Studies. These kinds of questions are just as important for digital projects as they are for more traditional forms of scholarly publication – in fact, more important. Who controls public discourse about something like public transport? In whose interest is that conversation being directed?

As a result, I have sought to actively engage faculty and students in Ghana, as well as various community organizations. I want to make sure that the project we are developing reflects their interests and creates possibilities for Ghanaians to shape its future growth. I also wanted to gather as much feedback on the project as possible, and that process will be ongoing, particularly as we publicly unveil the project. The project is so much richer for these interactions. I have been gratified by the excitement and engagement from many people in Ghana, but those interactions and community partnerships have also generated new and exciting opportunities for future growth that enabled me to envision a short, medium, and long-term plan for the project.

Our advisory board is, likewise, drawn from people both in Ghana and the US/Europe. It brings together tech experts, scholars with expertise in relevant fields, people working on transport mapping projects elsewhere on the continent, representatives of community partner organizations, and leaders in other digital initiatives in Ghana. Having such a wide range of perspectives makes the project richer and helps us identify what makes Accra Wala unique. The advisory board was involved in some of the early stages of the project and they will be involved again as we start to test the beta version over the next year.

Importantly, however, one of my goals in working with so many community partners is to ensure that I don’t step on the toes of people already doing good work in Ghana. I am well aware that it’s a privilege to be able to work on this sort of project without the expectation of financial compensation. So I have no interest in duplicating the good work of Ghanaians in the digital sphere. Where possible, I want to see how we can collaborate to support each other’s work. But, in some cases, those conversations have led me to drop parts of the project that were originally planned (e.g. route-planning) because they are being covered elsewhere. Because app and web development is such a vibrant field in Ghana, it’s challenging to stay on top of everything that’s happening, but social media is a huge help in this regard.

Working within these transnational networks can be difficult. Working with so many different people – coupled with the realities of limited funding and other resources – has meant that the project took longer to develop than it might have otherwise. And in that process you sometimes move into and out of relationship with partners as the project changes or the slow pace leads individuals or institutions to (understandably) lose interest. I’ve embraced the idea of “slow DH”, as Jim McGrath calls it, and used this longer timeline and slower development process to more actively engage students in the work of developing, designing, marketing, researching, and testing the site. This DH project, in other words, has been a pedagogical experiment as much as a research process, and it has led me to engage in new and exciting ways with students in Detroit as well as students in Accra.

I work with lots of people and institutions in Ghana that are far more technologically sophisticated and skilled than I am, and I am grateful for their assistance. This project has, however, been developed using very limited funding and a lot of creative resource utilization and good will. Keeping that in mind, I try very hard not to abuse that good will or otherwise monopolize funds that could be spent paying someone for their contributions.

The other challenge, of course, is distance and time. I cannot afford the time or expense necessary to be in Ghana as much or as often as I might like. This has also often slowed down the project. Again, social media and digital technologies can help a great deal, but the on-the-ground work that is really necessary to get the project going is often crammed into summer research trips. Being strategic about how to plan and time research and development work has been key, and working with students during the academic year and summer terms has been very helpful in moving the project forward. Being actively engaged in the relevant communities over a long period of time is also helpful in sustaining the project and securing effective partnerships and buy-ins.

Another major part of what makes this kind of project possible on such a shoestring budget – but which is not necessarily captured adequately in a list of partnerships – are all of the pieces of open source software and projects like Open Street Maps that are developed and maintained often by transnational teams. And, of course, this project relies on the open-source data for the trotro routes, collected through the Accra Mobile project. Had they not already done that data collection, this project would have taken much longer and been far more expensive. Members of that team, including the Agence Française du Développement, have worked with us from the start, and they have been generous with the use of that data, making it publicly available for hackathons and other purposes.

When do you see Accra Wala being available to the public and where can people go to learn more about it?

We hope to have a beta version of the site ready by January – if you want to test it or if you want to produce example media or itineraries, please reach out! We will publicly release the site in Ghana through a number of public events in summer 2020. It will be publicly available from that point forward. The website is www.accrawala.com, but there’s nothing there yet. You can keep track of progress on Facebook and Instagram @accrawala and on Twitter at @accramobile. We’re working on marketing materials and public outreach more actively in the Fall thanks to the help of a student intern, so there should be more coming soon.

Have you learned anything about Ghana, automobility, or Africa more generally from bringing this project to fruition? What do you hope the public takes from it?

One of the things that makes me most excited about this project is that it enables us to bring the street to life in a way that I could never accomplish in the narrative form of a book or journal article or blog post. In the process of developing this project and working with students and community partners, I am more convinced than ever that the senses are critical to our understanding of place. This is incredibly challenging for historians – how do we understand and convey the sensation of historic places, events, people? But, as my students note again and again, you only truly understand a different reality when you’re confronted with the lived reality of the everyday – in this case, the sensation of the street. I hope that by documenting the realities of everyday life from the perspectives of people living in the city and from historical perspective that we can generate new kinds of conversations about African urbanism and possibilities for alternative futures. What might it mean to take something like the trotro system seriously? What lessons can we learn from this system and its history that might help us develop approaches to transport issues in cities like Detroit? And what kinds of assumptions and historical legacies are implicit in our contemporary policies and practices?

Jennifer Hart is an Associate Professor of African History at Wayne State University, where she teaches courses in African History, World History, Digital Humanities, and History Communication. Her book, Ghana on the Go: African Mobility in the Age of Motor Transportation, was a 2017 finalist for the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association. She blogs atwww.ghanaonthego.com, and you can find her on Twitter @detroittoaccra.

Previous DSS 2019 sessions

Class #1: Gathering Places, Religion and Community in Milwaukee.

Class #2: On the Line: How Schooling, Housing, and Civil Rights Shaped Hartford and its Suburbs.

Class #3: Curating Southern California history @LAhistory

Class #4: Los Angeles and murals in the Robin Dunitz collection

Class #5: Take a Stand: Architecture Matters, PLATFORM

Impressive Jennifer. A lot of hard work.

LikeLike

Lovely Comments on the Art Exhibition · Brilliant! Very Much enjoyed the show. · What wonderful creativity – a joy to view!

LikeLike