Editor’s note: This it the second post in our series for November, “Metropolitan Consumption.” All other entries for the theme can be found here.

By Clif Stratton

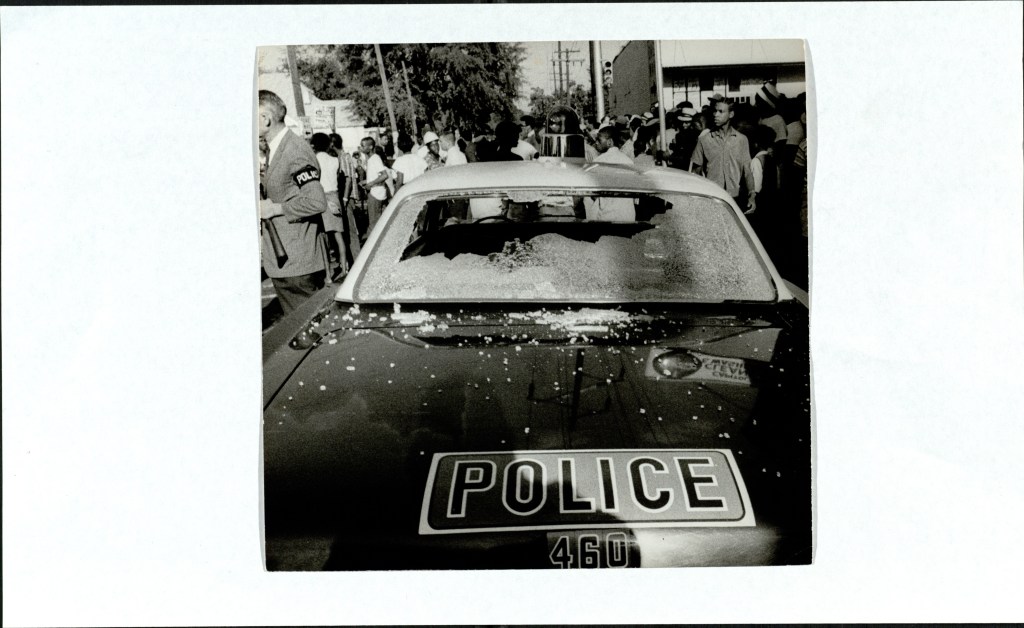

Atlanta will mark the sixtieth anniversary of the Summerhill Riot (hereafter Summerhill Rebellion) in 2026.[1] The spontaneous revolt of the urban poor occurred on September 6, 1966 after Atlanta Police Department (APD) officer Lamar Harris fired three bullets at twenty-five year-old unarmed motorist and autotheft suspect Harold Prather after Prather fled his vehicle on foot. Prather survived two gunshot wounds after a stint in the hospital, but the shooting lit a fuse in a neighborhood described by Pastor Roy Williams of the Summerhill Civil League as “a powder keg.” Within hours, residents of Summerhill, Peoplestown, Mechanicsville, and other southside neighborhoods gathered in protest at the site of the shooting, at the intersection of Ormond Street and Capitol Avenue.[2]

In a WAOK radio address less than two hours after the shooting, Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) Chairman Stokely Carmichael called for an organized protest at 4 p.m. that afternoon. SNCC members brought a sound truck, and residents aired their grievances. The grassroots rebellion had swelled to about 1,000 Atlantans by early evening. While protests, including those in Atlanta, following the 2020 police murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis were decidedly multiracial, an overwhelming majority of the participants in the Summerhill Rebellion of 1966 were Black, reflecting the populations of Atlanta’s poorest communities.

That Tuesday in Summerhill, law enforcement presence was heavy, and clashes between police and protestors resulted in property damage, scores of minor injuries, and seventy-two arrests. Thankfully, no one was killed. Perhaps against his better judgment, Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr. arrived in Summerhill to attempt to calm the swelling crowd. Protesters rocked the police car atop which Allen stood, causing him to fall to the pavement. But compared to other urban rebellions of the 1960s–Watts (1965), Detroit (1967), Washington, D.C. (1968)–Atlanta’s Summerhill Rebellion and the city’s later Boulevard and Dixie Hills revolts were tame. Summerhill ended in a matter of hours, not days.[3]

Still, befitting Atlanta’s slogan, “the city too busy to hate,” white and Black power brokers in government, business, and journalism, along with some of the city’s most prominent civil rights leaders, including Ralph Abernathy, swiftly condemned SNCC’s alleged role in fomenting violence among an unsuspecting and otherwise docile urban poor. “The spark of violence ignited by a few reckless and irresponsible individuals touched off an explosion of civil disorder that shattered Atlanta’s long record of racial amity,” stated Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr., criticizing SNCC the morning after the rebellion.[4]

Even if the Summerhill Rebellion was decidedly less destructive than contemporaneous rebellions in other American cities, the conditions that sparked it were certainly kindred. When the Council on Human Relations of Greater Atlanta shot back at Mayor Allen’s characterization of the violence as the work of subversive outsiders, it described “the [national] pattern” as “tragically familiar–slums, unemployment, poor schools, continued segregation and a police incident.”[5]

Though the council did not mention it, Summerhill was fast descending into food apartheid, too.[6]

Historian Marni Davis counts fifteen grocery stores on Georgia Avenue, Summerhill’s commercial heart, in 1950. That number dropped to eight by 1960 and four by 1970. At the time of the rebellion in 1966, the handful of grocery stores in the neighborhood offered little sustenance to residents, many of whom lacked the means to travel further in search of affordable, nutritious food. Making matters worse, those shop owners were predominantly white, their prices were high, and their food was often of poor quality. Racist treatment by certain shop owners added insult to injury.[7]

What structural forces account for Summerhill’s rather rapid descent from a thriving neighborhood replete with bakeries, groceries, repair shops, churches, synagogues, schools, a butcher shop, a dental clinic, an icecream shop, and a movie theater to a neighborhood devoid of steady access to affordable, nutritious food? How have residents and supporters sought to reverse the trend since that rebellious inflection point, including during the neighborhood’s ongoing, convulsive round of gentrification?

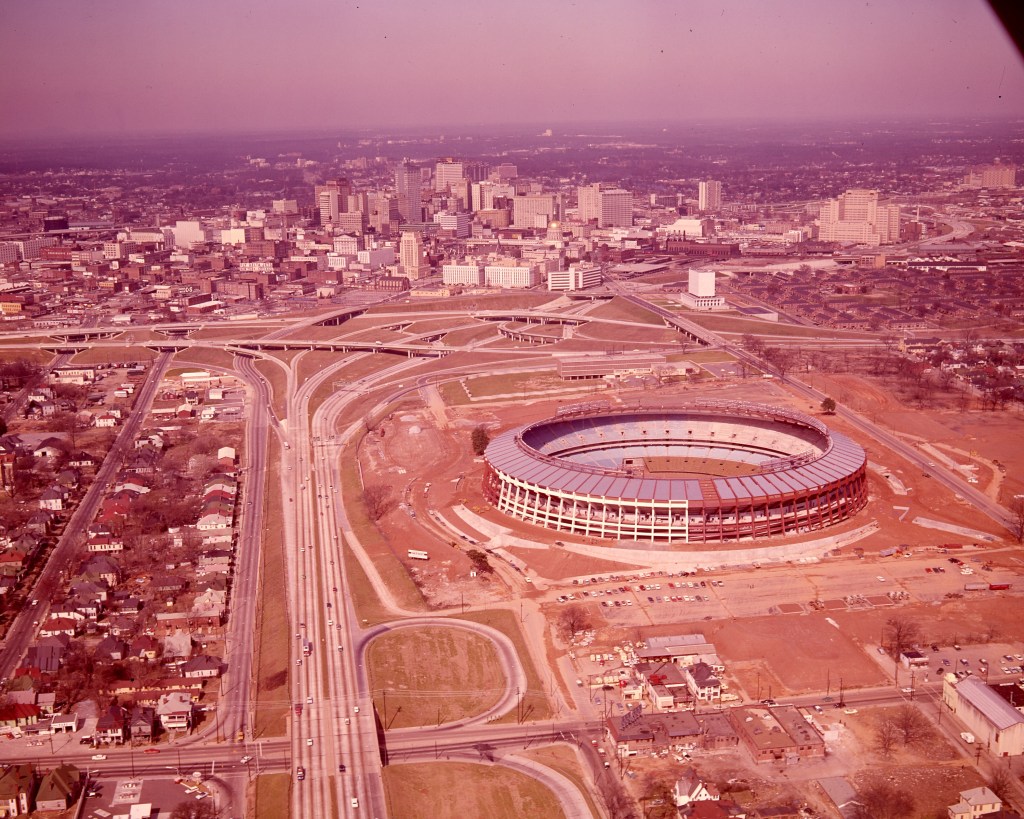

One context certainly not shared by all cities from which urban rebellion sprang during the 1960s was the disruption caused by the construction of massive stadiums, arenas, and athletic complexes dedicated to the consumption of sports. The intersection where Officer Harris shot Prather and at which residents gathered in protest sat four blocks south of Atlanta Stadium, just beyond the southern edge of its expansive surface parking, capable at the time of hosting 4,000 vehicles. During the rebellion, hundreds of Georgia state troopers occupied the stadium’s tunnels and adjacent lots awaiting orders to assist APD in bringing “rioters” to heel.[8]

Atlanta Stadium opened for Major League Baseball just five months before the rebellion. Led by sluggers Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews, the Braves dramatically became the first franchise to relocate to the former Confederacy. The stadium and the successful courting of the Braves were the crowning infrastructural and civic achievements of Mayor Allen’s first term. It followed on the heels of his predecessor William B. Hartsfield’s massive urban renewal projects that included slum clearance for an ultimately failed whites-only public housing project in the 1940s and interstate highways in the 1950s. Summerhill and its western neighbor, Mechanicsville–once seamlessly mapped to each other–were now bisected by a walled expressway. Summerhill had been a thriving mixed-class, multiracial, multiethnic neighborhood from the 1920s through the 1940s, composed of African Americans and European émigrés from Russia, Greece, Hungary, Poland, and Syria. But by the mid-1960s, the neighborhood had been reduced to a Black slum through redlining, white flight, and urban renewal. Then, in 1966, it got a professional baseball stadium.

When it opened, Atlanta Stadium added insult to historical injury and inaugurated a particularly pernicious form of social disruption that would continue throughout the Braves’ fifty-year tenure in the neighborhood. The stadium further stifled rather than reinvigorated local businesses, including groceries and restaurants. As Davis reports, the three blocks on the north side of Georgia Avenue were bulldozed to make way for stadium parking. Once the municipally-owned stadium opened, its financial backers wanted not just gate and parking receipts but concession receipts as well. That desire incentivized the Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium Authority to channel consumer spending to concession vendors inside the stadium, rather than to the few Summerhill businesses that remained outside.[9] Generous projections of widespread economic benefits repeatedly failed to bear out over the life of Atlanta Stadium, but especially in the neighborhoods immediately surrounding the ballpark.[10]

Less than a month before the Braves’ opening night, the Community Council of the Atlanta Area, Inc., a nonprofit social planning organization formed in 1960, issued a report drawn from fifteen weeks of group interviews with residents of Summerhill and Mechanicville. The neighborhoods’ lack of grocers was included among a list of other findings that pointed to structurally racist city policies and empty promises: “poor housing…no recreation…low income…alcoholism…illiteracy…poor health…exploitation of people…despair and ingrained skepticism about the promises of help.” Quoting the council’s report in the Atlanta Journal, reporter Wayne Kelley described “a very high rate of malnutrition, including just plain starvation.”[11]

But Journal readers might have forgotten the council’s portrait of the stadium’s surrounding slums if they also read the Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine, whose Andrew Sparks lavished praise on the new park, writing that “beauty fills the entire stadium from landscaped parking lots and elegantly decorated club rooms to the [color coordinated] concession stands and food commissary.” Spark extolled the stadium’s “Chinese egg rolls hot from a concession stand” and the pleasure of “drinking a cool liquid from a frosty tin.”[12]

The contrast between the council’s description of hunger in the slums and Sparks’s description of beautiful abundance at the games could not have been starker.

It is impossible to determine the extent to which the public absorbed the sort of boosterism promoted by Sparks and others. If attendance records are any indication, many did not believe the hype. Although the new stadium had a capacity for 50,000 fans, it averaged less than 3,000 season ticket packages sold during the Braves’ first ten years in Atlanta.[13] Still, by the end of the inaugural season, economic impact studies such as that of William Schaffer, a master’s candidate at Georgia Tech’s School of Industrial Management, were promising sweeping returns on the city’s investment in Major League Baseball. In a study underwritten by the Braves, the anticipated multiplier effects suggested that $30 million in “income” for Atlantans was not out of the realm of possibility. Ticket revenue topped the list of income sources at $2.7 million, followed by food and entertainment, not including concession sales, at $2.5 million. Concession sales and lodging were next on the list at about $1.5 million each.[14]

Little, if any, of that multiplier capital found its way into Summerhill’s food system. The Constitution’s Bruce Galphin reported almost a year after the Summerhill Rebellion, “There are no chain grocery stores in Mechanicsville or Summerhill, but a succession of small groceries whose principal offerings seem to be beer and wine.” Making matters worse, Galphin wrote, “Almost every item of food costs the slum-dweller more than it does the middle-class [white] Atlanta housewife at her shopping center.”[15]

The situation would generally remain the same for the next three decades. City government largely neglected the nutritional and other needs of Summerhill. Nonprofits like Emmaus House, an Episcopal antipoverty effort that provided fresh fruits and vegetables to neighborhood youth in the late 1960s, filled some gaps. Similarly, the Georgia Avenue Food Cooperative, founded in 1991 by Georgia Avenue Church minister Chad Hale, not only provided fresh food to the community, but enlisted its members in the distribution process as a way of forging stronger community bonds. Still, it wasn’t enough.[16]

Olympic Dreams

Thirty years after the Summerhill Rebellion, Atlanta hosted the 1996 Summer Olympic Games. When it was announced in 1990 that the city would host the games and the Atlanta Committee for the Olympic Games planned to build another sports stadium in Summerhill, reactions were contentious.

Douglas Dean, CEO of Summerhill, Inc., a community-led revitalization enterprise, told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (AJC) that he was optimistic that “a community destroyed by a stadium 25 years ago, will once again thrive with the beginning of a new stadium.” But Dean was rightly skeptical of the city as a good faith partner. The original stadium project had also come with promises of restoring the neighborhood to a vibrant, livable community, but with little follow-through.[17]

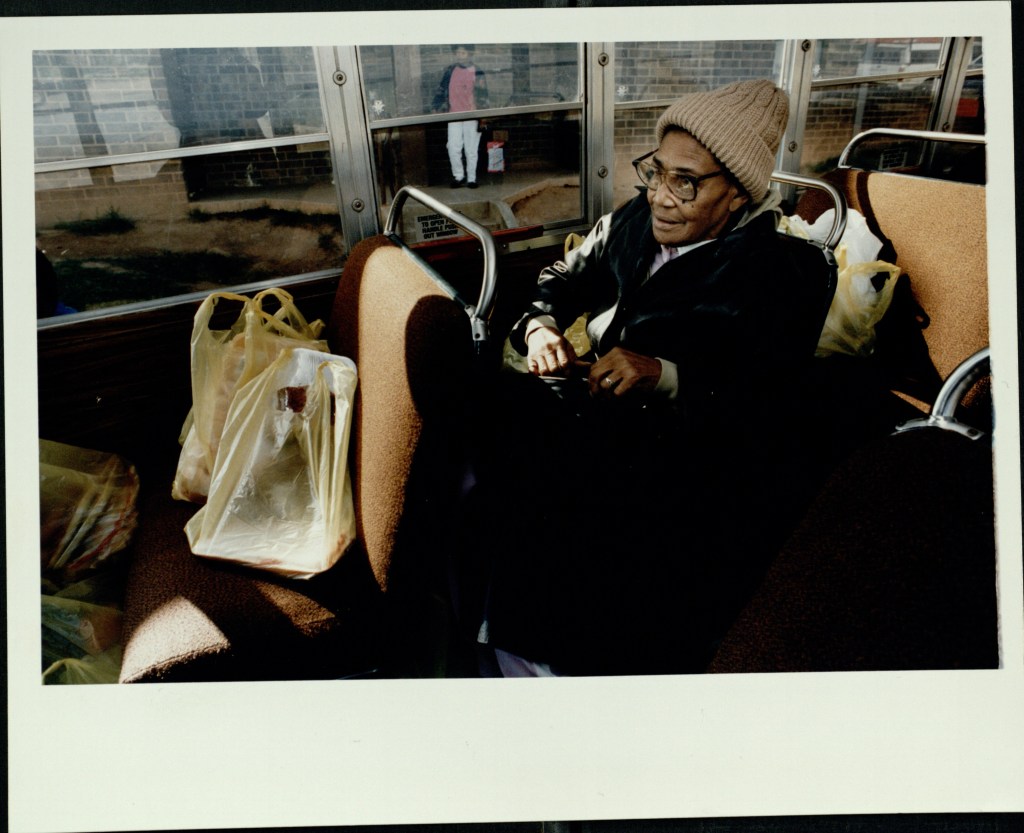

Other observers also balanced skepticism and hope. “If nothing changes in the shadow of these gleaming arenas, residents still will travel miles to buy an average-priced loaf of bread,” wrote AJC reporter Michelle Hiskey. When Hiskey interviewed Alice Russell, a longtime Mechanicsville resident, Russell recalled a time when there were “plenty of neighbors and no vacant lots. We had everything we needed along here: a drug store, a hardware store, grocery stores, a hospital, a café, an ice cream parlor.”[18]

Meanwhile, Rick McDeavitt, president of the non-profit health organization Georgia Alliance for Children, noted the stark contrast between food provisions on Atlanta’s white Northside and its Black Southside in the same AJC article: “Where I live on the Northside is within spitting distance of Kroger, Winn-Dixie, and Cub Foods. It’s almost bewildering that as many people eat down there, they have to take a cab to the grocery store or go to a curb market where there is no fruit or fresh vegetables.”[19]

The Centennial Olympic Games dramatically reshaped Summerhill. The Braves got a new stadium, the old one was demolished, and the neighborhood experienced modest gains in housing revitalization. Still, by the turn of the twenty-first century, residents had little access to healthy food. “There’s nothing over here you can buy,” Mattie Jackson told the AJC in 2000. “We need to go shop just like other people shop and buy the right kind of food to feed our children.”[20]

Food Apartheid No More?

In 2023, Summerhill finally got a supermarket. It took the Braves’ leaving the area for it to happen. Following the team’s flight to suburban Cobb County in 2017, Georgia State University moved into Turner Field and retrofitted it for football with plans for student housing and more sports infrastructure. Carter, an Atlanta-based real estate investment and development corporation, also hoped to transform the once-thriving Georgia Avenue, about six blocks north of the site of the Summerhill Rebellion, into one of the most desirable in-town corridors. The area had been vibrant decades before mayors Allen and Hartsfield ordered so-called slum clearance in the 1950s and 1960s. In charting the changes in Summerhill, Josh Green of Urbanize Atlanta, a commercial real estate and development magazine, described in 2024 a tale of two neighborhoods: “Call it Atlanta preservation at its finest, a shining example of adaptive-reuse development, or gentrification run amok, but you can’t deny the [recent] changes have breathed life and vitality into a moribund section of town that’d left so many Braves fans scratching their heads for a generation.”[21]

Life and vitality for whom? The development spurred by the Braves’ suburban flight, the arrival of Georgia State University, and Carter’s ambitious plans for Summerhill rapidly changed the neighborhood’s foodscape. In 2023, Publix opened its doors at the neighborhood’s northern end within sight of a gentrified Georgia Avenue commercial district. Mayors of major cities typically don’t attend supermarket grand openings. But Atlanta mayor Andre Dickens attended this one, in a nod to the long-awaited arrival of fresh food in Summerhill.[22]

With Publix and a slew of upstart hipsterish restaurants and bars including Little Bear, Halfway Crooks Biergarten, Wood’s Chapel BBQ, Southern National, Maepole, and Zenshi along Georgia Avenue and Hank Aaron Drive (formerly Capitol Avenue), Summerhill is no longer a neighborhood without food options. Even the Braves, now firmly entrenched in suburban Cobb County, have partnered with the Food Well Alliance and Atlanta Housing to support community farming on the site of a former 175-unit public housing project, several miles south of Summerhill.[23] But with the neighborhood’s breakneck pace of gentrification since the Braves moved north, longtime Summerhill residents who have fought since the 1960s for a livable neighborhood in the shadows of two stadiums are likely facing another round of displacement, negating whatever the benefits of food access finally realized.

Clif Stratton is Associate Professor of History at Washington State University. A 2010 recipient of a Ph.D. from Georgia State University and born and raised in Atlanta, Stratton is the author of Power Politics: Carbon Energy in Historical Perspective (Oxford University Press, 2020) and Education for Empire: American Schools, Race, and the Paths of Good Citizenship (University of California Press, 2016). Email him at clif.stratton@wsu.edu.

Featured image (at top): Aerial photograph of the Atlanta, Georgia, area taken in October 2017, with a focus on SunTrust Park northwest of downtown Atlanta in the Cumberland neighborhood of Cobb County. The Atlanta Braves moved to SunTrust Park in 2017. Carol M. Highsmith, photographer, October 31, 2017, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

[1] The revolt in Summerhill was at the time and has subsequently been referred to as the Summerhill Riot. I use the term rebellion rather than riot to question the notion that the actions of those engaged in resistance are without direction or purpose. For more on this distinction, see Elizabeth Hinton, America on Fire: The Untold Story of Police Violence and Black Rebellion Since the 1960s (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2021), 4-7; Janet Abu-Lughod, Race, Space, and Riots in Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007), 10-11; Scott Kurashige, The Fifty-Year Rebellion: How the U.S. Political Crisis Began in Detroit (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017), 19-20.

[2] Atlanta Journal, September 7, 1966; Williams quoted in Winston A. Grady-Willis, Challenging US Apartheid: Atlanta and Black Struggles for Human Rights, 1960-1977 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), 117. Grady-Willis describes the chronology of the rebellion vividly. In 1973, the Atlanta Braves hired Lamar Harris, the white officer who shot Prather, to provide off-duty private security for Hank Aaron at Atlanta Fulton-County Stadium. Aaron’s pursuit of Babe Ruth’s all-time home run record prompted racist death threats that the team deemed serious enough to enhance security in the bleachers near Aaron’s post in the outfield. See Tom Stanton, Hank Aaron and the Home Run that Changed America (New York: HarperCollins, 2004), 67. The title of this essay derives from a favorite quote: “You can’t eat racism and war.” See Daniel Denvir, All American Nativism: How the Bipartisan War on Immigrants Explains Politics as We Know It (London: Verso, 2020), 10.

[3] For a comprehensive national analysis of these rebellions, see Hinton, America on Fire.

[4] Statement by Ivan Allen on Civil Disorder in Atlanta, Tuesday, September 6, 1966, series XV, box 19, folder 7, City of Atlanta Records, Atlanta History Center (hereafter CAR, AHC).

[5] Council on Human Relations of Greater Atlanta, Statement, September 8, 1966, series XV, box 19, folder 7, CAR, AHC.

[6] See Ashante Reese, “Black Food Geographies: Race, Self-Reliance, and Food Access in Washington D.C. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2020), especially chapter 2, for a rich treatment of the structural forces that produce “food apartheid.” Reese’ s analysis goes beyond the scope of this essay, which is focused on how public-private endeavors to create spectator spaces for mostly white, middle class consumers contributed to a dirth of affordable, healthy food options. This shift in the use of urban space forced Black residents to exercise resiliency, self-reliance, and creativity to obtain food in ways their white, middle-class counterparts rarely had to,

[7] Marni Davis, “Streetscape Palimpsest: A History of Georgia Avenue,” 2019.

[8] “A Day to Forget,” Atlanta Constitution, September 7, 1966; “15 are Injured in Rioting Here as Negroes Toss Rocks at Police,” Atlanta Constitution, September 7, 1966; “Snick March Squelched, 10 Seized,” Atlanta Constitution, September 8, 1966.

[9] Davis, “Streetscape Palimpsest.”

[10] Larry Keating, Atlanta: Race, Class, and Urban Expansion (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001), 97-99.

[11] Wayne Kelley, “City’s Shame in Shadow of its Pride: Atlanta’s Plush Stadium Towers Over Slum’s Poor,” Atlanta Journal, March 18, 1966.

[12] Andrew Sparks, “Beauty and Baseball,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution Magazine, April 10, 1966, 15.

[13] Clayton Trutor, Loserville: How Professional Sports Remade Atlanta and How Atlanta Remade Professional Sports (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2021), 109-110.

[14] Statistics Extracted from the Atlanta Braves Economic Impact Study Conducted by the Georgia Tech School of Industrial Management, XV-B19F15, City of Atlanta Records, Atlanta History Center; Schaffer et. al., “The Economic Impact of the Braves on Atlanta: 1966,” February 1967, Industrial Management Center, Georgia Institute of Technology, XV, B21, F18, CAR, AHC.

[15] Bruce Galphin, “Needed: A Road Out,” Atlanta Constitution, July 31, 1967.

[16] See for example, Jeff Nesmith, “Sister Mary Rose: Children Find a Real Angel, Atlanta Journal and Constitution, July 4, 1968. For more on Emmaus House’s antipoverty efforts, see LeAnn Lands, Poor Atlanta: Poverty, Race, and the Limits of Sunbelt Development (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2023). On the Georgia Avenue Food Co-op, see Bill Banks, “The Co-op Way,” Furman Magazine 47, 1 (Spring, 2004), 2-9; H.M. Cauley, “Summerhill: Worker and co-op need each other: Food minister also gives clients a chance to put something back,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, February 21, 2008.

[17] Paulette V. Walker, “Stadium area links survival to Olympics,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 27, 1990.

[18] Michelle Hiskey, “Residents Know Talk Won’t Deliver Gold,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, December 27, 1992.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Melissa Turner, “Neighborhoods: Olympic Vision Takes Shape,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, October 9, 2000.

[21] Josh Green, “Flashback: Recalling the ‘before’ version of Summerhill’s vibrant strip,” Urbanize Atlanta, March 1, 2024. Visit Urbanize Atlanta’s Summerhill collection of articles, and one will likely find the pace of change overwhelming. See https://atlanta.urbanize.city/neighborhood/summerhill.

[22] Terry Shropshire, “Summerhill announces Publix store, construction of mixed-use development,” Atlanta Voice, May 28-June 3, 2021; 11Alive Staff, “Long-awaited Publix opens in Atlanta’s Summerhill neighborhood,” June 21, 2023.

[23] The Leila Valley farm is 4.5 miles south of the intersection where the Summerhill Rebellion occurred in 1966, and may well serve those displaced by rising rents and property taxes in Summerhill. See “Braves unveil community farm,” mlb.com, July 13, 2025, https://www.mlb.com/braves/video/braves-unveil-community-farm. Also see: https://engageatlantahousing.org/leilavalley.

One thought on “You Can’t Eat Home Runs: Hunger and Games on Atlanta’s Southside”