The ninth and final post from our 2023 Graduate Student Blogging Contest is from Fauziyatu Moro. She writes about how stumbling onto the important mementos of immigrants, while doing fieldwork in Accra, led her to develop her thesis topic, which broadens understanding of the lives of migrants by looking at their leisure activities. To see all entries from this year’s contest check out our round up here.

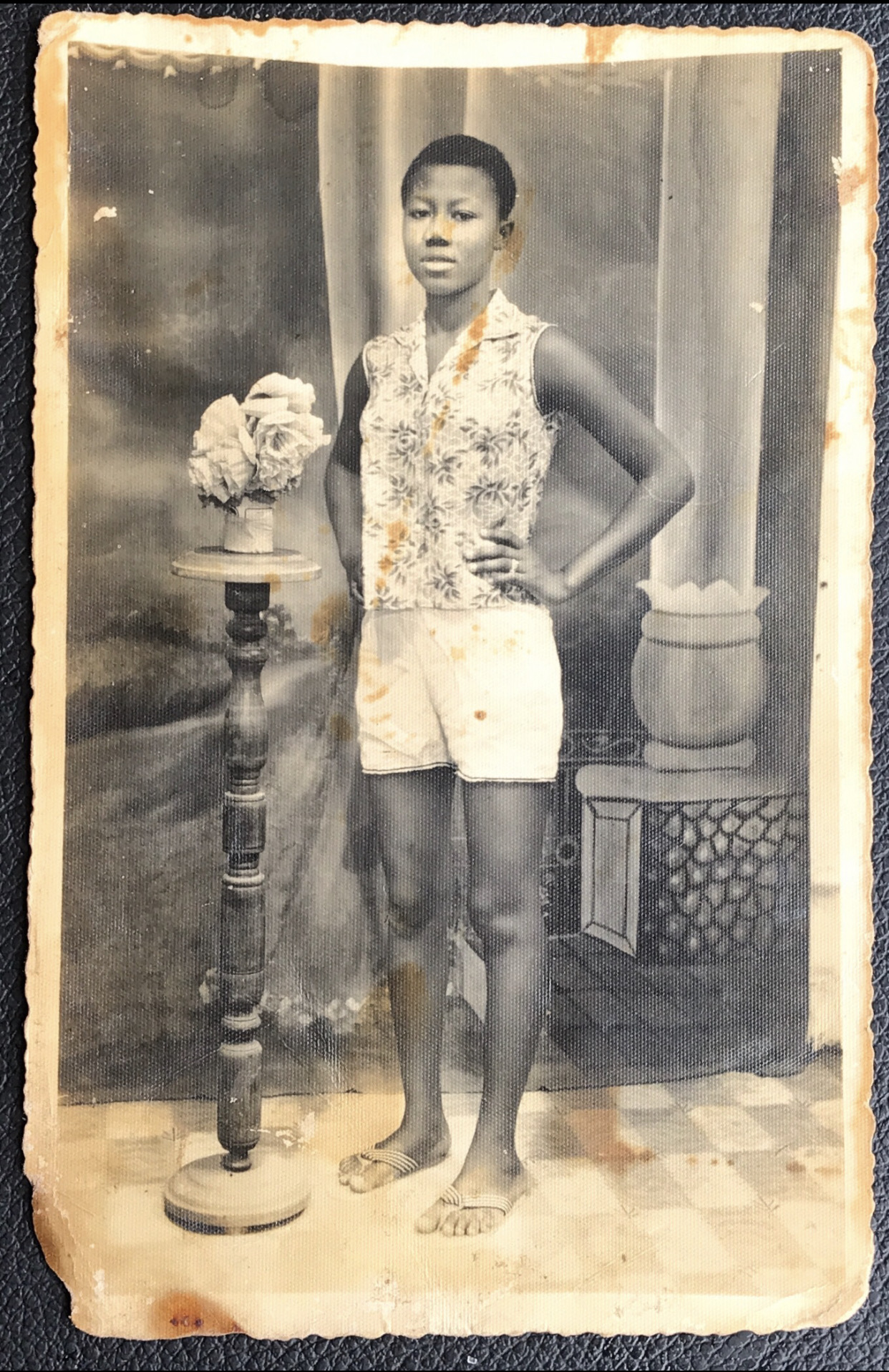

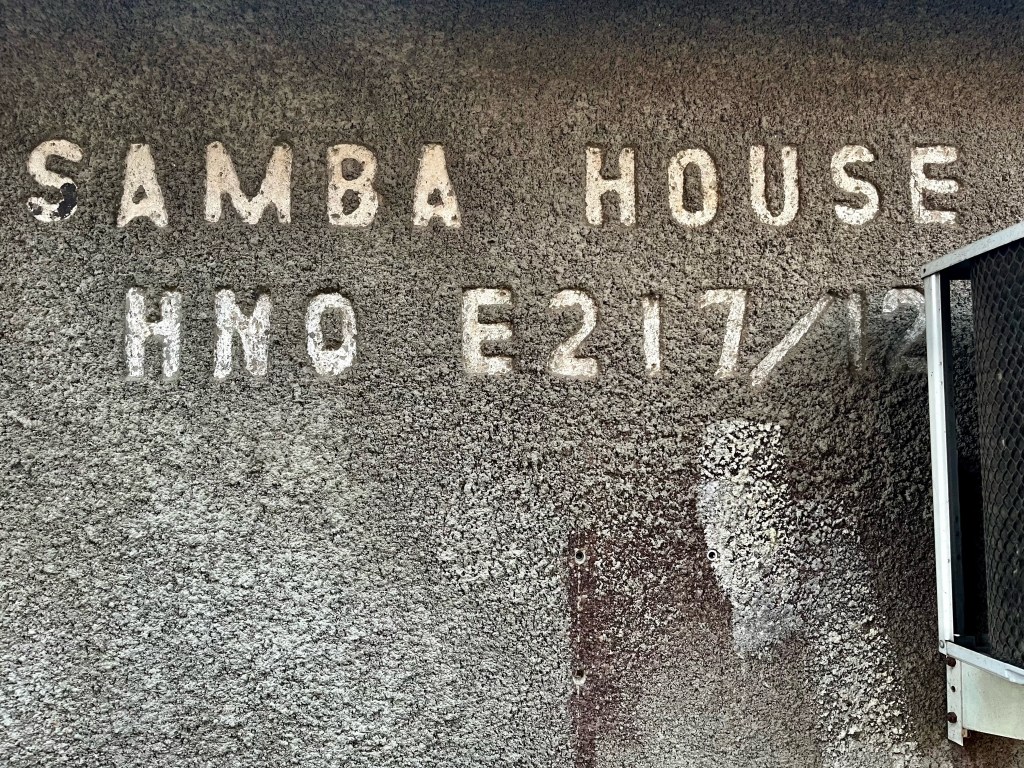

Pictured below, to the left, is a young Hajia Fatima Musa, a resident of Nima and one of my research participants. To the right, is the flip side of the same photo with the business stamp of the photographer who took the photo. It reads: E. N. Ogazi Niger Photo Work ❊ Nima-Accra ❊ Day and Night Service ❊ P.O. Box 22. Hajia Fatima, now well into her eighties, showed me this photo among others in her photo archive when I visited her on July 7, 2021, during my preliminary fieldwork. For each photo presented, she offered an elaborate description, but unlike the others, her description of this particular photo was lengthier, partly because it was the only one with a stamp that became a story in and of itself during our conversation.

Hajia Fatima’s photo points to the continuities between migration and labor, but it also evidences the social aspirations and life of migrants that transcend the popular narratives which limit migrants to their economic endeavors. The personal archives of intra-Africa migrants offer fresh insights into the myriad social ways that these migrants negotiated their lives in the urban milieu. In this piece, I demonstrate the usefulness of these personal archives during the fieldwork process by honing in on how a stumble on one such archive unearthed the many potentials of my dissertation research on migrants’ leisure lives in Accra.

The conversation with Hajia Fatima began with my inquiry about her moviegoing life and what mementos she had of her days at the cinema. In response, she recalled some of her memorable times in Nima’s first cinema, Dunia Cinema, including the debut showing of the popular Indian film Mother India, and Nima’s migrant women’s proclivities for Indian films. The photos she presented served as a kind of visual aid with which she threaded bits and pieces of her leisure life, and the one above offered another layer to our conversation. The photo was taken on one of the days young Hajia Fatima made a detour to E. N. Ogazi’s photo studio on one of her occasional trips to Dunia Cinema for a showing of Indian films. As was the practice of the time, when personal cameras were scarce and a huge luxury, residents of Accra relied on photo studios and the gyinahɔ gye form of photography to memorialize some of their fun moments and social activities.[1] The second part of our conversation unfolded when I asked her about the stamp on the back of the photo. She gave an account that took us, yet again, on an ecstatic journey into her leisure life and how it intersected with the life and work of other migrants in Nima, particularly E. N. Ogazi and one other photographer who lived in the town at the same time. E. N. Ogazi was, thus, one of two photographers in Nima when Hajia Fatima was growing up. He was an Igbo man who migrated from Nigeria to Nima to work as a photographer, and his studio was located at the eastern end of the town. Issaka, the only other photographer in the town, was a Chamba man from northeastern Ghana, and he had his studio adjacent to the Dunia Cinema.

The circumstances that shaped my encounter with Hajia Fatima Musa and her archive began in 2021 when I envisioned, as a dissertation topic, moviegoing in Nima between 1957, when work on Dunia Cinema began, and the 1980s, when it collapsed. Brief moments of intermittent preliminary research over the years and endless reflections on conversations with research participants, such as the one with Hajia Fatima Musa and the images that inspired most of it, consequently led to a broadening of the scope of my research into an exploration of various migrants’ leisure pursuits and how they shaped the socio-urban landscape of Accra in the twentieth century. My journey to this new research trajectory was facilitated by the words and material culture of these migrants, such as Hajia Fatima’s photo, which recalibrated my research away from a narrow topic to a macro one that reflects the social ambitions of the migrants I intend to center in Accra’s urban history.

It has always been apparent to me that migrants’ leisure, more broadly, could be a lens through which the intricacies of social life and the dynamics of spatial access for different groups of migrants in Accra could be assessed and understood. But the groundbreaking revelation came when I discovered the wealth of knowledge inherent in, specifically, migrants’ personal archives. In effect, a new methodological approach emerged for me grounded in the idea of movement in mementos: for instance, the way that Hajia Fatima Musa’s photo captures movement as it relates to people migrating into new spaces (internal and intra-Africa migration), the positionality of different groups of migrants within a typical migrant town (proximity, or the lack thereof, to important social landmarks), and migrants’ conscious pursuit of leisure (moviegoing and trips to photo studios). In essence, the photos and other mementos, the migrants’ voices, and the relics of the sociocultural vista of the migrant town, such as photo studios and cinema houses, together became the pivots on which my methodological framework sits.[2]

Seen in broader terms, this new methodological framework allows for the uncovering of an alternative story of Nima, other zongos (a Hausa word meaning “strangers’ quarters” or “strangers’ towns”), and yan zongo (translated as people of the zongo), which eschews the unidirectional accounts shrouded in the developmentalist language of chaos, labor, and health concerns.[3] Zongos, found largely in Ghana and Nigeria, and the yan zongo are corollaries of intra-Africa migrations, which constitute two thirds of all movements by Africans. However, this fact is often obscured by the scholarship and media narratives that privilege South–North migration of Africans.[4] Nima, the focus of my dissertation research, is Ghana’s largest zongo.

Located some three miles north of Accra, Nima became the latest addition to the migrant enclaves in the city in the 1930s, preceded by Tudu, Sabon Zongo, and Cow Lane, among others. It began with a small entourage of Fulani cattle herders and caretakers, led by the Muslim cleric, Mallam Amadu Futa, who settled in the then unoccupied Gã indigenous land.[5] Over time the town’s population increased, as many more migrants from the preexisting migrant towns relocated there due to congestion, and new groups from other West African countries and the northern territories of the Gold Coast (now Ghana) made their way to Accra, a major commercial entrepot offering a wide range of economic incentives.[6] However, like most zongos, Nima is often labelled a “slum,” a misnomer that strips the town of the history and form which sets it apart from the country’s slums, many of which are transient.[7] Certainly, on its face, Nima resembles the favelas, barrios, and shantytowns of the world in light of its “informal” status, position as a low-income residential space, and location on the fringes of the city. But a deep dive into its origins and the lives of its residents reveals a unique and complex sociopolitical coordination which my dissertation research seeks to unravel through the leisure of its residents.

I am undertaking this historiographical endeavor by coming to the town through its residents—yan zongo—and their leisure choices. My resolve to understanding the town and its residents in this way is inspired by the sources available to me and is intended to advance the claim that the lived experiences of intra-Africa migrants, specifically the three generations of migrants in Nima who lived between the 1930s and the 1980s, transcended their status as laborers or hewers of wood and drawers of water. In their narratives and personal archives lie the many alternative perspectives to migration and migrant life that counter the entrenched narratives seen in the colonial and state archives, which position migrants in relation to labor.

Across the continent, scholarship and narratives on leisure have taken on a massive turn with publications surfacing from different areas of Africa’s subregions. Phyllis Martin’s work on Congo Brazzaville and Laura Fair’s on post-emancipation Zanzibar, among others, have offered a foundational basis for the ever-burgeoning field of scholarship on leisure and social life in Africa, and my work contributes to this historiographic trend, albeit from the angle of Africa’s yan zongo.[8] It contends with the key question: “What is made visible about an African city, like Accra, when stories of the leisure exploits of its strangers is foregrounded?” which it aims to answer, in part, through the stories emerging out of personal archives of the yan zongo.

Fauziyatu Moro is a PhD student in the African History Program at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, with a minor in African Cultural Studies. She specializes in nineteenth- and twentieth-century West Africa, and her research interests include migration, urbanization, urban popular culture, and gender in Africa. Her current research sits at the intersection of migration, urban leisure, and placemaking. It maps the social lives of migrants in Ghana’s largest migrant enclave as a way to highlight the role of intra-Africa migrants in the transformation of the socio-political landscape and cultural efflorescence of the nation’s capital, Accra, in the twentieth century.

Featured image (at top): “Makola Market, Accra” (2004) Exil-Fischkopp, Wikimedia Commons.

[1] Gyinahɔ gye, an Asante-Twi term which literally translates as “stand there and take,” is a colloquial used by people of Hajia Fatima’s generation and older to describe the outdated style of studio photography involving the use of plate cameras.

[2] James Ferguson’s methodological concept “ethnography of decline,” which he employed in his investigation of the copper trade boom and subsequent decline in urban Zambia was key in my own conceptualization of the idea of movement in mementos. For Ferguson, choosing to approach his topic through this methodological/theoretical framework enabled him to avoid a teleological analysis of the experiences of the residents of Zambia and to, rather, “concentrate on the social experience of ‘decline’ itself.” See: James Ferguson, Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zambian Copperbelt (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999).

[3] Ato Quayson, Oxford Street, Accra: City Life and the Itineraries of City Life (Durham: Duke University Press, 2014), 5.

[4] See Bruce Whitehouse, Migrants and Strangers in an African City: Exile, Dignity, Belonging (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012)

[5] Jack Arn, “Third World Urbanization and the Creation of a Relative Surplus Population: A History of Accra, Ghana to 1980,” Review (Fernand Braudel Center) 19, no. 4 (1996): 413-443.

[6] Intermarriages between these intra-Africa migrants and members of various indigenous ethnicities in the country, coupled with reproduction, also contributed to the expansion of the town. These intermarriages also facilitated interethnic integration and the prospects of citizenship for many of the migrants in Nima. For instance, Hajia Fatima Musa’s father hailed from Mali and her mother from northeastern Ghana. See: Deborah Pellow, Landlords and Lodgers: Socio-Spatial Organization in an Accra Community (West Port, CT: Praeger, 2002) and Victoria Okoye’s piece, “Becoming Local: Histories of ‘Nigerians’ in Accra,” The Metropole: The Official Blog of the Urban History Association, December 16, 2019, https://themetropole.blog/2019/12/16/becoming-local-histories-of-nigerians-in-accra/.

[7] My choice of the word zongo is in keeping with how these migrants perceive their built space as opposed to how state and developmental agencies conceive of and describe migrant towns in Accra.

[8] Phyllis Martin, Leisure and Society in Colonial Brazzaville (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996); Laura Fair, Pastimes and Politics: Culture, Community, and Identity in Post-abolition Urban Zanzibar, 1890-1945 (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2003). See also: Nate Plageman, Highlife Saturday Night: Popular Music and Social Change in Urban Ghana (Durham: Duke University Press, 2013); Emily Callaci, Street Archives and City Life: Popular Intellectuals in Postcolonial Tanzania (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017); Oluwakemi M. Balogun et al., ed., Africa Every Day: Fun, Leisure, and Expressive Culture on the Continent (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2019).