Inga Gudmundsson McGuire writes about how discovering that her ancestor was a Pittsburgh architect inspired her to learn more about him and ensure that his memory and legacy are not forgotten in the eighth entry in our 2023 Graduate Student Blogging Contest. To see all entries from this year’s contest check out our round up here

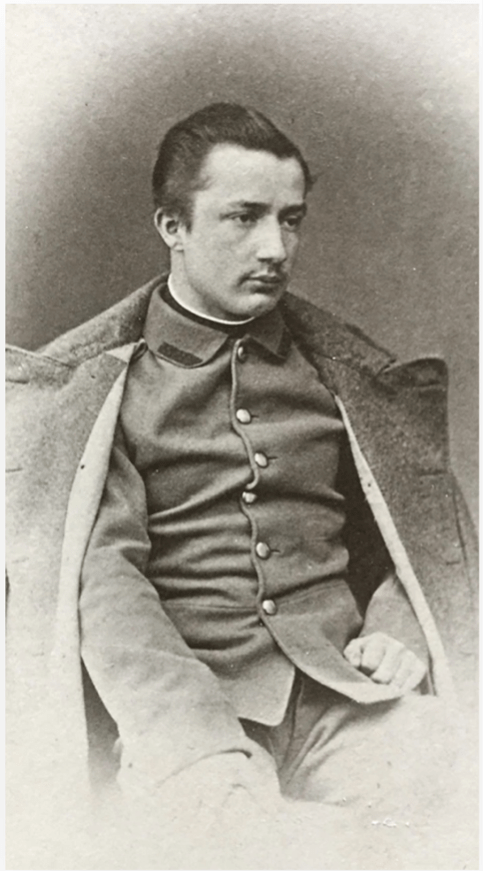

I walked past the same framed photo for over twenty years. Overlooked, and frankly forgotten, next to the dozens of other photos of long-dead relatives that line the stairway of my childhood home, I had never thought to ask who the stoic young man, posed in his white military uniform, was. Although it sounds extreme, the day I inquired about the framed photo, which I would learn was a portrait of my great-great-grandfather Joseph Stillburg, was the day the trajectory of my life changed forever.

After discovering he had been a leading architect in Pittsburgh but was almost completely forgotten over time, researching Joseph Stillburg has become my working master’s thesis. This is a story of how stumbling upon Joseph Stillburg’s life and prolific career has led me to ask myself what is Joseph Stillburg’s legacy, and how do I answer that question if his memory only partially lives on through his descendants and the histories of the extant buildings he designed?

When Joseph Stillburg died on December 23, 1923, his death went unannounced in the local newspapers. Once a leading architect of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and referenced in historic newspapers as “prominent” and “well-known,” Stillburg’s illustrious career had already begun to slowly disappear from the collective memory.[1] Books and articles on the development of Pittsburgh at the turn of the twentieth century hardly—if at all—mention Stillburg. Was Joseph Stillburg bound to be forgotten? Did the advent of new building technologies and the changing landscape of Pittsburgh, where buildings were constructed just to be torn down and replaced, lead to the removal of Stillburg’s designs to a point at which the memory of him dissipated? Even though I do not know why Stillburg seemed to be forgotten so quickly after his death, what I have learned about his architectural career demonstrates his importance and that it warrants more attention and research, in large part due to the extant buildings that are currently being preserved and recognized on the local and national levels.

Who was Joseph Stillburg?

Joseph Ludwig Stiller von Stillburg was born on August 24, 1847, to Josef Stiller von Stillburg and Regina Pertschnigg in Austria.[2] By 1868, Stillburg had immigrated to the United States.[3] Stillburg first moved to Springfield, Illinois, where he began work as a draftsman.[4] Four years later, in the spring of 1872, Stillburg was a practicing architect.[5] In 1871 a fire destroyed a large swath of downtown Chicago, leaving devastation “beyond calculation.”[6] Architects were needed to rebuild the city, and Stillburg heeded the call in 1872, with fellow architect, and former mayor of Springfield, Thomas J. Dennis. [7] While credited in a list of architects who helped rebuild the city after the fire, no buildings designed by Stillburg & Dennis from Chicago are known.[8] Chicago is undoubtably where Joseph Stillburg’s architectural career started to take off, but no memory of his time here was passed down through the family, and a lack of written record on Joseph Stillburg for this time period means that little is known about his early years as an architect. In 1879 Joseph Stillburg married and moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[9]

What is Stillburg’s Legacy?

While the majority of Joseph Stillburg’s designs have been demolished over the last century, some of his buildings have been preserved, thereby enabling Joseph Stillburg’s inclusion in Pittsburgh’s rich architectural history dating from the turn of the twentieth century. It was during this time, in the last half of the nineteenth century, when a new wave of Ecole des Beaux Arts architects and their apprentices started to change the built environment of the United States.[10] Names like Richard Morris Hunt, Frank Furness, and Henry Hobson Richardson all paved the way in designing in new architectural styles, most notably Richardsonian Romanesque.[11] While not trained at the Ecole des Beaux Arts and not remembered or recognized nearly as much as some of the famous architects listed above, Joseph Stillburg took their practices and used the popular architectural styles in his own designs. Below are some of Stillburg’s most notable designs, which distinguish him as an important architect who should be remembered.

In 1883, Joseph Stillburg designed the Eberhardt and Ober Brewery Company Racking & Wash & Storage Building for William Eberhardt and John Ober. Stillburg designed the four-story, brick commercial building with Romanesque features, steel framing with a central tower, and a pyramidal roof. A corbeled cornice lines the top of the flat roof.[12] The property was placed as a district on the National Register for Historic Places in 1987.[13] Having one of Joseph Stillburg’s designs on the National Register elevates Stillburg to the national level. It also brings pride to myself and my family, to know that one of our ancestors designed buildings that are still utilized and loved today.

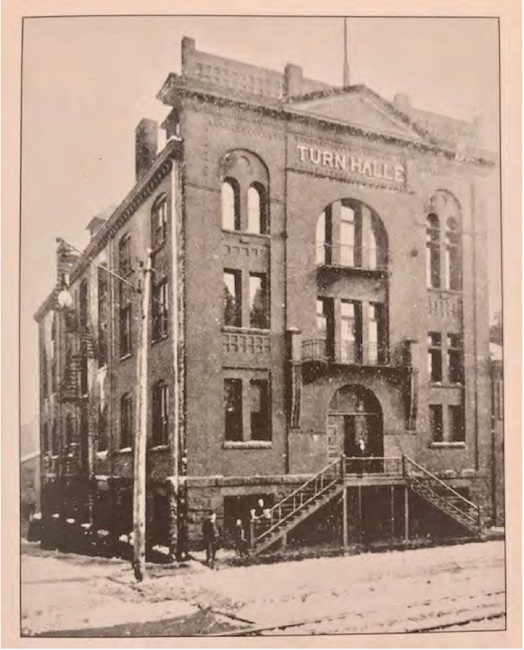

The Allegheny Turn Halle building at 855 S. Canal Street (see featured image, at top) is currently in the nomination process to become a local historic landmark. If successfully nominated, it will join other landmarked Stillburg designs including The Eberhardt and Ober Brewery buildings and Troy Hill Fire House No. 11.[14] Dedicated on November 28, 1889, this building stands as a testament to Joseph Stillburg’s expertise.[15] The four-and-a-half-story, brick and stone, Richardson Romanesque-style building features a latticework frieze, arched recesses along the main elevation, and brickwork that delineates each bay. All of Joseph Stillburg’s designs, including the Allegheny Turn Halle, have an attention to detail that conforms to the styles of the day, such as Richardsonian Romanesque, but creates unique features that set his buildings apart. Stillburg also deployed terra cotta, steel, and other new building technologies to create stronger buildings that were more fireproof. For instance, according to the nomination, the Allegheny Turn Halle building is presently one of only six buildings within Pittsburgh city limits that has obtained the highest fire safety ranking. [16] Seeing buildings like the Allegheny Turn Halle, which had not been on my own research radar before learning about the nomination, solidify my hopes to return Joseph Stillburg’s legacy to the collective memory. The more extant buildings designed by Stillburg that we can research and preserve, the better chance there is that he receives the recognition I know he deserves.

Unfortunately, many of the buildings Joseph Stillburg designed have long been demolished. The first residential design attributed to Joseph Stillburg was Henry A. Laughlin’s mansion on Ellsworth Avenue.[17] A newspaper from 1935 notes the residence was “one of the show places of Pittsburgh” in its day.[18] The building was torn down in 1935 for six “modern” houses built with salvaged materials from the 1880 residence.[19] Another important building long demolished is the Gusky Department Store. Joseph Stillburg designed the business block in 1884 for Jacob M. Gusky, the successful department store owner.[20] The formal opening on January 1, 1885, showcased the completed four-story, brick and steel-frame building. By the 1980s the building had been torn down and replaced by the PPG Place complex.[21] There are only a small number of Joseph Stillburg’s buildings that have not been demolished and replaced. The legacy of Joseph Stillburg is yet to be recovered; my hope is that other people will continue to join me in researching and writing about Joseph Stillburg with the goal of answering this question and reviving his life and career in the way that he deserves to be remembered.

After stumbling upon his career in 2018, Joseph Stillburg’s life and legacy has continued to amaze me with its complexity and layered history. I was surprised this past spring when I opened Walter C. Kidney’s Pittsburgh’s Landmark Architecture, an all-encompassing history of the built environment of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County written in 1997, and saw that Kidney suggested “an interesting Pittsburgh architect is waiting to be discovered or better known: the extravagant Joseph Stillburg, perhaps.”[22] With the help of oral histories from family and historical research, the man in the framed photo is now a major driver of my own academic career. What I have come to realize is that when you go looking into someone’s legacy and try to piece together the memories of someone who lived over a century ago, the story that is unveiled becomes a part of your own story. As a historian and emerging historic preservationist, I hope that a century from now someone will look back on the research I am doing for Joseph Stillburg and silently thank me, just as I have done with so many historians and preservationists before, for reviving the story, career, and life of someone who was on the brink of being forgotten to time. While his legacy is still in question, the memories that have been shared and the research that has been conducted make me confident that I am on the right path to answers and that the memories of Joseph Stillburg will no longer be left to just to stumble upon.

Inga Gudmundsson McGuire is a second-year Masters of Historic Preservation student at the University of Georgia. Inga hopes to add the Museum Studies Certificate to her degree, supplementing her history undergraduate degree and public history concentration from James Madison University. Her current working thesis is on Pittsburgh architect Joseph Stillburg and focuses on what contributions Stillburg made to the field of architecture and how his legacy impacted the landscape of Western Pennsylvania today. Originally from Virginia, Inga spent two years as a Teach For America Corps member in North Charleston, South Carolina, before moving to South Carolina and working as an on-call historic preservationist for ICF. After a graduate assistantship in UGA’s Digital Imaging Lab, Inga currently works for the Carl Vinson Institute of Government, providing historical research for various projects in Western Georgia. She is the 2023-2024 vice president of the Student Historic Preservation Organization at University of Georgia and recently was awarded the 2023 John G. Thorpe Young Professionals & Students Fellowship from the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy.

Featured image (at top): Allegheny Turn Halle, 855 Canal Street (c. 1890), photo courtesy Preservation Pittsburgh

[1] Controller Morrow, “He Saw Them Dying,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, August 28, 1892.

[2] Johann Hammer, “Joseph Stillburg Research,” Genealogy Austria, 2022. The future architect was considered illegitimate until his parents married on February 19, 1851. The Stillburg family gained their title through the military achievements of Joseph Stillburg’s grandfather, Lieutenant Colonel Josef Elder von Stillburg.; “He Saw Them Dying,” Pittsburgh Dispatch, Sunday, August 28, 1892. Joseph Stillburg’s childhood followed in his family’s tradition of military service and he became a soldier in the Austrian army.

[3] 1870; Census Place: Springfield, Sangamon, Illinois; Roll: M593_282; Page: 480B. There are many unknowns when it comes to the early years of Joseph Stillburg’s career. While these gaps in the research are partially due to a language barrier when researching his time in Austria, other reasons include minimal digital records, including city directories for Chicago and timing of moves right after and before the 1870 and 1880 censuses.

[4] City Directory, Springfield, Sangamon County, Illinois, 1869, My Heritage.; 1870; Census Place: Springfield, Sangamon, Illinois; Roll: M593_282; Page: 480B.

[5] City Directory, Springfield, Sangamon County, Illinois, 1872, MyHeritage.

[6] “Appalling Disaster,” The Rock Island (IL) Argus, October 9, 1871; “Notice,” Chicago Tribune, January 27, 1872.

[7] “Notice,” Chicago Tribune, 5. The pair ran an advertisement together as partners in the Chicago Tribune three months after the fire, in late January of 1872: “Stillburg & Dennis, Architects and Superintendents, 215 South Clark St. are prepared to make Designs, FULL Details, specifications, and superintend such work as may be entrusted to them, on reasonable terms.” Interestingly, Stillburg’s name is first in the advertisement.

[8] “Industrial Chicago: The Building Interests,” (The Goodspeed Publishing Company, Chicago:1891), 121, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000005962518&view=1up&seq=160.

[9] Wisconsin Historical Society; Wi Marriage Records Pre-1907, #02014. The couple remained in Pittsburgh, adding four boys to their family, three of whom would reach adulthood. The first two buildings in the city attributed to architect Joseph Stillburg date to 1880. The Bissel Block and Laughlin Residence set Joseph Stillburg on a trajectory of prominence as a well-known architect in Pittsburgh and beyond at the turn of the twentieth century. He went on to design the Western Pennsylvania Exposition Buildings, Gusky Department Store, and countless other hotels, residences, schools, churches, and commercial buildings.

[10] Leland Roth and Amanda C. Roth Clark, American Architecture: A History, 2nd ed (New York: Routledge, 2015), 223. Following the Civil War, a new resurgence of construction, coupled with new building technologies and better architectural education, changed the built environment of large emerging cities such as Chicago, New York, and Pittsburgh. Industrial giants in steel, oil, and railroads emerged in the Gilded Age, along with the need for larger factories, multi-story commercial buildings, and opulent mansions.

[11] Roth, American Architecture, 266-275.

[12] “Eberhardt and Ober Brewery, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.” Historic Structures, https://www.historic-structures.com/pa/pittsburgh/eberhardt_and_ober_brewery.php, February 17, 2023

[13] Eliza Smith Brown, “Eberhardt and Ober Brew District,” National Register for Historic Places Form, 1987, National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior, https://gis.penndot.gov/CRGISAttachments/SiteResource/H009660_01H.pdf.

[14] “Local Historic Designations,” Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, accessed August 15 https://phlf.org/preservation/historic-plaque-program/local-historic-designations/.

[15] “A Monument to Muscle: The New Allegheny Turner Hall Dedicated,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, November 29, 1889.

[16] Matthew Falcone and Jeff Holmes, “Allegheny Turn Halle,” City of Pittsburgh Historic Landmark Nomination, Prepared by Preservation Pittsburgh, 2023, https://themetropole.blog/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/dd83e-alleghenyturnhalle_nominationbinder_signed.pdf.

[17] “Henry A. Laughlin in Office,” Historic Pittsburgh, https://historicpittsburgh.org/islandora/object/pitt:MSP33.B006.F04.I04, accessed April 20, 2023. Son of James Laughlin, original partner of Jones & Laughlin Steel, Henry worked for the company, becoming general manager and later chairman

[18] “6 Homes to Replace Laughlin Mansion,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, October 27, 1935.

[19] “6 Homes to Replace Laughlin Mansion,” Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph, October 27, 1935. Henry Laughlin retired in 1909 and built a larger mansion in Chestnut Hill known as Greylock. This house is extant and was listed for $1,795,000 in 2021.

[20] “Notes,” The Sanitary Engineer 9(1884), 459, https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433108242359&view=1up&seq=475&size=175.

[21] “Red Cross Finds New Home,” Pittsburgh Press, March 3, 1974, 122; “A New View of the Business Environment,” Pittsburgh Press, November 10, 1981.

[22] Walter C. Kidney, Pittsburgh’s Landmark Architecture: The Historic Buildings of Pittsburgh and Allegheny County (Pittsburgh: Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, 1997) 278.