Editor’s note: This is the third post in our theme for January 2022, Urban Environmentalism. Additional entries can be seen at the end of this article.

By Claire Campbell

When the COVID-19 pandemic closed in, almost two years ago now, it threw our usual academic routines and practices into disarray. Classes “pivoted” to asynchronous, online platforms, or Zoom-boxes where we all became uncomfortably familiar with our students’ dorm rooms and other people’s houses. Libraries and archives closed; in-person conferences were cancelled. We began to see the effects on those who shouldered more home and family care, and the gap between women and men widen in research and publishing.

(Full disclosure: in March of 2020, my son was in kindergarten. Each day his teacher tried for an hour to teach spelling and math to twenty six-year-olds over Zoom. I will forever and always cherish the snippets I managed to write in that hour, both of us at the dining table, half my attention on keeping him focused, because it was such an incredulous, ludicrous, little victory.)

But COVID is only the pointed and immediate edge of a much larger set of problems. Whether or not a historian or a group of scientists choosing not to fly is going to keep our world habitable, the global climate emergency is, I hope, asking us to pay more attention to the (in)equity and consequences of research travel as we have understood it. We may not want to measure it out in coffee spoons, but we do need to see it in tons of carbon, and thus as an enormous privilege, something to be valued and even rationed based on triaged and multipliable worth. A colleague, for example, instituted a rule-of-three for himself several years ago: he flies only if the trip is genuinely necessary or highly valuable for his research; if it has another professional value, as for teaching; and if it adds some personal meaning or growth. Would this even divert more traffic to–and therefore more pressure for–lower-emission forms of transportation, or nurture more research exchange closer to home?

And this is not just about the environmental cost of travel. “I’ll spend a month [or six] in the archives” sounds lovely, to be sure…assuming you have family obligations covered, time set aside, and disposable income on hand. In other words, enormous personal autonomy underwritten by professional security. That is not the case for most of us, even those of us with professional security. It has a strangely sitcom-dad-on-a-business-trip feel; the quiet part–who will parent? how do we pay for it?–is never spoken out loud. Yet, this model of immersive travel continues to define the process and expectations of historical research. (My husband, who is a scholar of contemporary African-American literature, has a slightly easier time of it. As he said at the beginning of our sabbatical, “I just want to read books, write books, and not talk to anyone.”)

Environmental historians face a special tangle. We study places, often places where we don’t live. My current work explores the coastal cities of Atlantic Canada and how they have altered their waterfronts and watercourses over the long nineteenth century. Since 2013, though, I have lived in central Pennsylvania, two days’ drive from Saint John, Halifax, and Charlottetown. (Relatively recently, I decided to focus any travel within a drivable radius, acknowledging the carbon dilemma. COVID, meanwhile, has brought that down to a bikeable one.) I’ll spare you the first-world-problem, woe-is-me story of losing a longed-for, carefully-planned trip out east last year…suffice to say it hurt. I am writing about places I can’t visit.

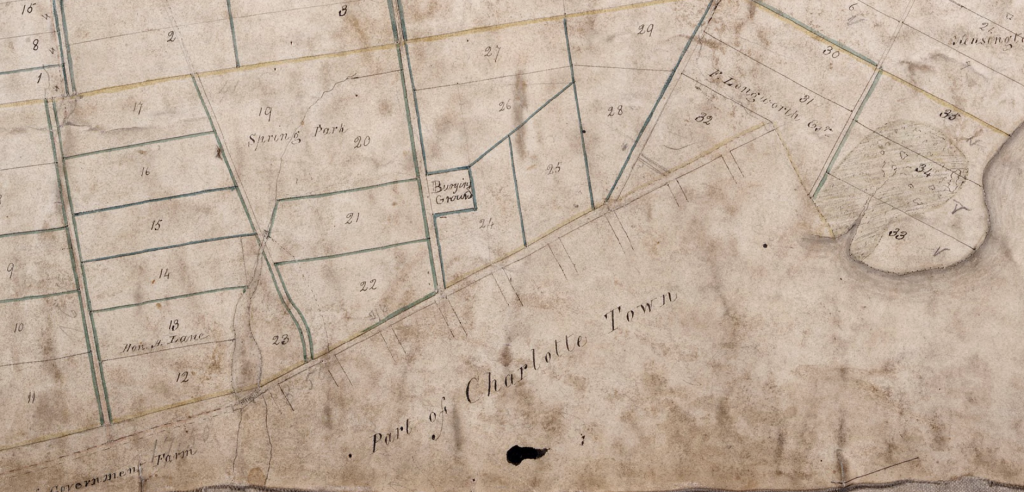

David Rumsey Map Collection.

Which has been fine, up to a point. I lived in Halifax for several years and miss it dreadfully–I daydream by walking its streets, and overflow with tears the few times I’ve managed to get back. I know Charlottetown reasonably well, or at least well enough to not get lost. Writing about these cities has been a balm for an expatriate. As I pore over a map, I can picture myself in the breeze by the harbor, facing the shadows of a back alley, feel the incline up Citadel Hill. The artifact appears in three dimensions, if only in my imagination. But now I’m trying to make sense of the harbor of Saint John, a city that I’ve driven through on my way to somewhere else, but beyond that, don’t know at all. I’m writing blind.

Hence the tangle. Stuck in central Pennsylvania, I have relied almost entirely on digitized material. And it’s been a Godsend. To be clear: I am not, and have no aspirations to be, a digital historian. I use a computer, as I imagine we all do, to read and write. I have no interest in manipulating a text; I simply want to be able to read it. Digitized materials mean I can read–closely and carefully and for as long as I need to–maps and brochures and legislation and newspapers and whatever else has been made available. (I can also wear yoga pants, and make coffee, and not freeze to death, unlike nearly every reading room I’ve ever been in.) While historians are increasingly “desperate to get back to the Archives”–and sure, after almost two years at home, I’d love a few (child-free) weeks in Ottawa or Charlottetown, too–the pandemic slips into larger structural problems with those same archives’ capacity for in-person or on-site research: notably underfunding and understaffing, which were concerns long before COVID. Archival staff are essential for all things analog, but remote research highlights the enormous and largely invisible labour of digitization and communication that has kept archives, in a sense, open. I have been humbled by the generosity of archivists and librarians who have responded to my emails with humour and kindness and any help they can offer. The world needs more archivists, full stop.

My work on coastlines draws heavily on maps, plans, and charts, and here digitization is especially helpful. Online collections offer the opportunity to scrutinize pale, fragile maps of any size that would otherwise need to be handled with special care. In fact, I have been able to turn more into visual study by having these at scroll-wheel convenience. To complement the cartographic, I can weave in a textual counterpart, like a run of newspapers, or a body of colonial legislation, or transcripts of debates from the House of Commons. There’s an ease of movement, both physical and mental, between bodies of sources that otherwise would be impossible, or would take a lifetime.

For my students, too. My Urban Americas class–which, ironically, I was teaching during The Great Pivot of 2020–was able to examine materials from cities they knew (New York) and visit, for the first time, those they didn’t (any city in Canada). There was a wonderful sense of expansiveness in the classroom, a feeling of almost whimsical possibility–let’s go to Montréal today!–but with the satisfyingly “deep dive” into primary sources. While my university has rushed to embrace “civic engagement,” this generally translates as short-term, management-inflected volunteer projects. The humanities, in contrast, can bring a broader view of “the civic,” of context and causality that situate our communities in much more complicated traditions and histories.

That said, working so much with digitized materials gives me pause and nurtures new insecurities about the legitimacy of my writing. What does it mean to assemble a narrative from items already designated as worthy of digitization? Perhaps only the acknowledgement that all record-keeping and history-making is selective, and digital records are no different. If digital access allows us to sample from archives thousands of miles apart, is the result innovative and integrative–and a responsible use of carbon–or wildly idiosyncratic? What do I miss by only emailing with archivists rather than having them look over my shoulder, see what I’m interested in, offer thoughts on my project, and volunteer other materials?

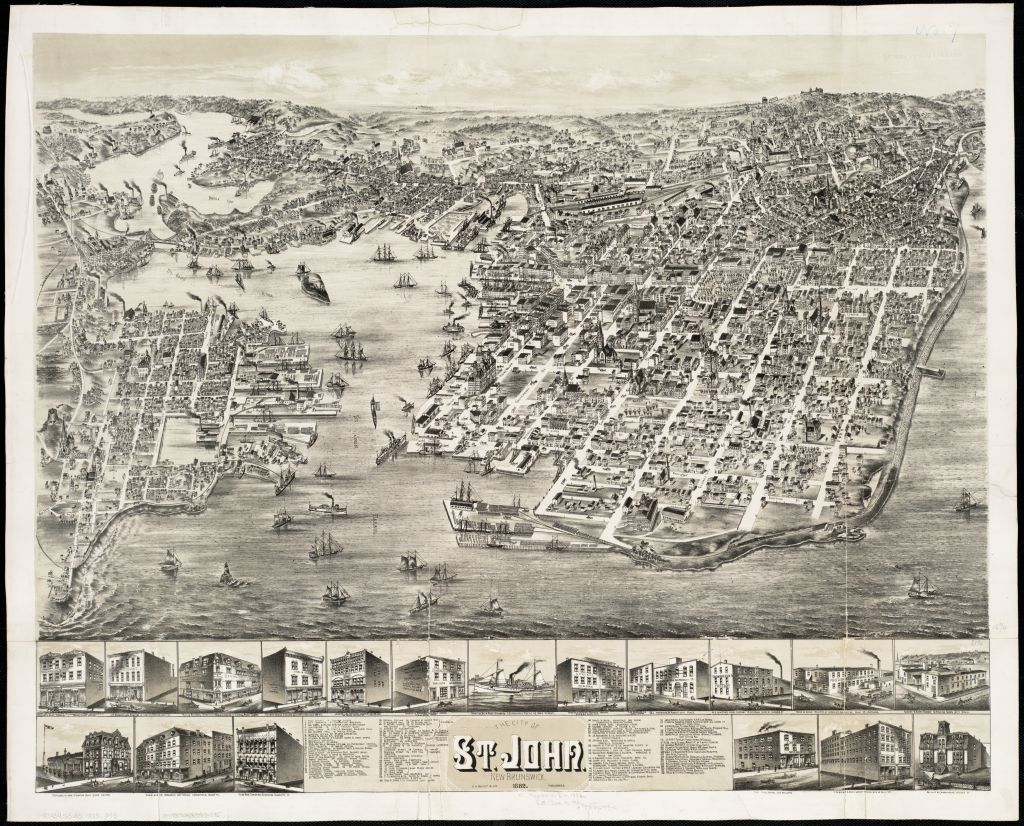

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center.

More fundamentally, can we really know a place through a screen? We know the problems that resulted from the colonial gaze in map-making: a deus ex machina view, flattening complex ecologies and cultures into two dimensions, rendering the world comprehensible and yet environmentally sterile in a single gaze. A map can’t convey the feel of a city–where the sidewalks crack, where you can glimpse the harbor, how the wind tunnels at street corners. And it certainly can’t immerse you in the patterns of life: how people move and how they fit in the streets, and where the trees shade, and where to get a good cup of coffee. It’s one of the reasons that even environmental historians are so loathe to give up travel–why we feel we need to be there.

Which is maybe why I’m struggling so much with the Saint John story. There obviously is a story here: a harbour where one of the largest rivers on the eastern seaboard meets the highest tides in the world; a city that became one of the most important industrial ports in Atlantic Canada; an enormous amount of land-making and loss of marshland. But I don’t have a hook. I don’t have a feel. I have read about it, but I haven’t walked it. I still see the city as a top-down, static, unpeopled, abstraction. I need to be there. At least for a little while.

Urban Environmentalism (January 2022)

- Driving into Environmental Law: Thurgood Marshall, Highway Construction, and the Overton Park Case (includes bibliography/reading list)

- Opposing Urban Energy Landscapes: Petitions and Letters against Coal Yards, Wood Yards, and Gas Stations in Montréal (1940s-1960s)

- The Racialized History of Philadelphia’s Toxic Schools

- Choosing Perpetual Management: Urban Runoff and the Origins of Its Mitigation

- The Greening of Detroit History

- “The Abyss”: Erosion and Inequality in the Urbanization of Amazonia

- Recreation and Reclamation of the “Richest Hill on Earth”

Claire Campbell is a professor of History at a small university in central Pennsylvania, where she tries to assuage her homesickness by teaching and writing about Canada all the time. Publications include Nature, Place, and Story: Rethinking Historic Sites in Canada (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017) and edited collections on the environmental history of Atlantic Canada.

Featured image (at top): George Neilson Smith, “View of the City of St. John, New Brunswick from Sandpoint, Carleton” (1848), Library & Archives Canada.