Editor’s note: This is the third in a series of articles during April that examine the construction of the Interstate Highway System over the past seven decades. The series, titled Justice and the Interstates, opens up new areas for historical inquiry, while also calling on policy makers and the transportation and urban planning professions to hold themselves accountable for its legacies. Additional entries in the series can be found at the bottom of the page.

By Ruben L. Anthony Jr. and Joseph Rodriguez

During the 1960s, cities across the country were bisected by new expressways. These freeways, as documented by scholars like the late historian Raymond Mohl, often impacted lower-income, minority communities, partly due to redlining that for decades limited investment. While property owners received compensation, renters did not. The destruction of long-lived residential and commercial centers had a lasting impact on urban residents. Scholars have largely failed to follow up on what happened after freeways were built. Where did displaced residents move to? What happened to commercial development in later years? How does freeway reconstruction (and expansion) continue to impact these communities? How does the memory of displacement mobilize opposition to reconstruction or bring demands for minority employment on new construction projects?

Between 1960 and 1971 twenty thousand houses were lost in the city of Milwaukee for highway development or for urban renewal projects. At least 6,334 of these lost houses can be attributed directly to highway development. Freeways were responsible for the largest public housing destruction in Milwaukee’s history. Freeway proponents in the city and state government pointed out that 41,000 housing units were built during the 1960s; ample compensation for the housing lost, they argued. While housing may have been replaced, many displaced residents could not afford the new housing. Often, landlords refused to rent to minorities. Race and income factored into determinations regarding whether a displaced family would receive housing. Also, during the 1950s and 1960s family displacement, particularly for those residing in the older inner-city areas, happened before the federal government instituted programs to assist residents with housing razed by highway development. The freeway displacements occurred simultaneously with the demographic explosion in the city’s African American population.

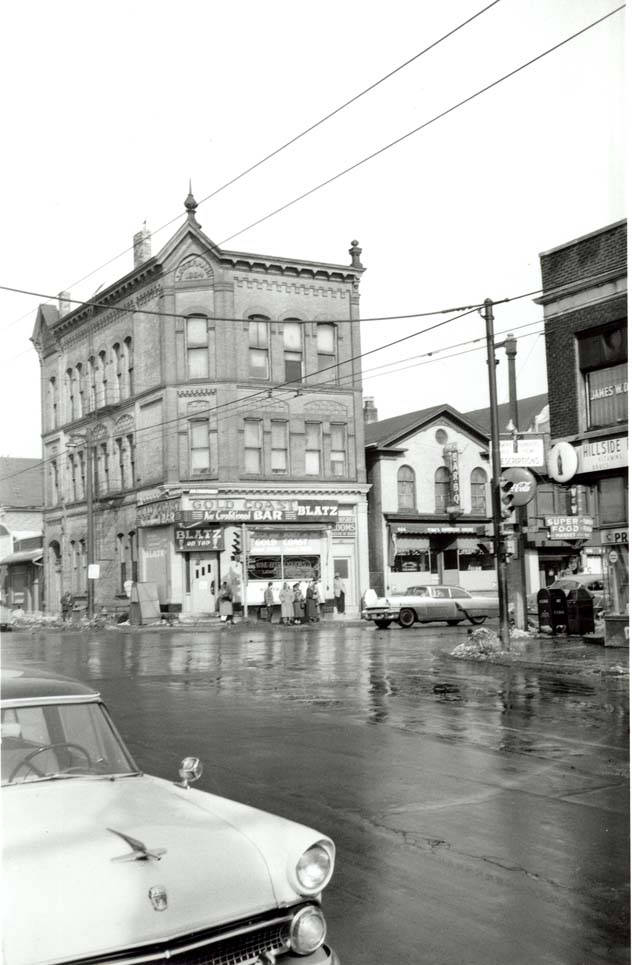

Documenting and memorializing residential and community displacement that occurred during urban renewal serves a purpose beyond developing a collective understanding of the nation’s inequities. During the 1960s the construction of one interstate freeway through Milwaukee destroyed the city’s vibrant African American neighborhood, Bronzeville, the heart of the Black community. While residents, bars, and restaurants relocated, no similarly concentrated cultural area ever reformed. Today, the memory of Bronzeville and its destruction persists in history books, photographs, oral history collections, and newspaper articles. Milwaukee’s city website celebrates “Bronzeville in an effort to revive the area as an entertainment and commercial center.” This vivid memory of Bronzeville’s destruction continues to inform opposition to any new plans to expand freeways in the city.

Residents that remained along freeway routes included African Americans, Poles, and Latinos on the city’s south side. All suffered from air pollution, high rates of lead poisoning, and increased asthma rates. A growing awareness of such negative health impacts contributed to a new environmental justice movement which demanded remediation and expanded public health services. Living near freeways lowered house values and functioned to preserve the south side as largely a community of immigrants and lower income residents. Immigrant and working-class communities adapted to the freeways by transforming the space below them into public space. The classic example is San Diego’s Chicano Park, where murals on the freeway abutments depicted the community’s history of displacement. In Milwaukee the space below the freeways provides parking for local social service agencies and a canvas for murals.

Freeways occasioned a rebellion when local residents witnessed destruction to the urban fabric. A series of freeway revolts swept the country beginning in the early 1960s, which sometimes resulted in the termination of projects after state transportation agencies had already razed houses. In wealthier parts of the city, ending freeway projects led to new development. However, in Milwaukee, on the African American north side, there remains a vacant swath of land where the the state purchased homes and razed them just before facing protests by a coalition of Black and white residents, which prevented the freeway route’s expansion.

While protests ended some freeway construction, the natural life span of freeways requires their reconstruction, and this leads to new fights over design and construction employment. Milwaukee is at the confluence of two major freeways–one north-south, the other east-west–that meet at the Marquette Interchange near Marquette University. Built in the 1960s, the Marquette Interchange underwent a major reconstruction between 2004 and 2008, referred to as The Marquette Interchange Project (MIP). The MIP was the largest freeway project in Wisconsin’s history. The over $800 million project was undertaken during democratic governor Jim Doyle’s tenure. The MIP’s location near Milwaukee’s poorer neighborhoods created the opportunity to use the project as a means to benefit local workers. The Wisconsin DOT (WISDOT) required the employment of local, disadvantaged Milwaukeeans and minority and female contractors on the MIP.

Ruben L. Anthony Jr. was the deputy secretary of WISDOT and coordinated the Disadvantaged Business Enterprise (DBE) program for the MIP. To encourage the hiring of minorities and women on the MIP, WisDOT provided construction companies with special hiring incentives and required that they enter payroll data into a civil-rights tracking system. In the past, because many of the construction companies in Wisconsin are unionized, prospective workers had been required to join trade unions and matriculate through their job selection process. Often, women and minorities faced entry barriers as they sought construction jobs.

WisDOT also divided bigger contracts into smaller projects, which gave DBEs the opportunity to serve as prime contractors or consultants. WisDOT also required sub-contracting on construction tasks that the state wanted DBEs to get experience performing. WisDOT also provided job training and regular, executive-level monitoring to ensure the hiring of minorities and women.

As a result of these efforts, the MIP employed about 1,000 inner city residents. At one point, 24 percent of the workers were women or minorities. WisDOT was able to include 74 DBEs that would not have normally been included on such a project. Many local workers hired on the MIP stayed in the industry. Other DBEs secured work afterward on other mega-freeway projects.

However, the shortcoming of the Marquette DBE program was that this level of success could only be achieved on mega-projects. WisDOT has not had the same success with projects costing less than $500 million. As political administrations have changed, many of the best practices established on the MIP were not continued. Additionally, DBE goals could only be assigned to federal projects. At times, the Wisconsin state legislature opted to finance projects with state dollars that did not require a DBE goal. This has proven detrimental, because the largest number of DBEs are located in southeastern Wisconsin near Milwaukee’s poor community. As result, many of the businesses that emerged out of the MIP have gone out of business or are struggling.

Even with DBE hiring initiatives, the MIP faced local opposition. Milwaukee Mayor John O.Norquist, long a freeway critic, denounced the project’s size and led an effort to shrink the project’s footprint and budget. Also, Milwaukee community organizations protested the MIP for not addressing mass transit deficiencies. These protests led the state to direct $97 million to fund local transit improvements.

Milwaukee became part of a national trend when Norquist called for the razing of part of the Park East Freeway through downtown Milwaukee. Norquist was part of the first anti-freeway movement, which blocked the completion of the area’s system in the 1970s. Built as part of an unfinished route to lakefront, the Park East Freeway ended abruptly after the anti-freeway movement thwarted its extension to the lake. In 2003, WisDOT along with the Federal Highway Administration approved taking down the freeway. Razing the mile-long elevated freeway freed up just under thirty acres for redevelopment.

Initially, razing the Park East appeared to offer little benefit to the city’s poor. New development did occur (albeit slowly due to the Great Recession), but as part of what John Hannigan has called the “fantasy city”: projects that lure upper- and middle-class professionals and tourists to the city. One major project that benefited from the freeway’s deconstruction was a new basketball arena for the Milwaukee Bucks, Fiserv Forum, completed in 2018. Fiserv proved very controversial as state and local taxpayers footed the bill for infrastructure improvements that benefited the wealthy hedge fund managers who had purchased the team from Wisconsin Senator Herbert Kohl. They received over $250 million in public money, which spurred a community movement called “Fair Play” that demanded state funds to improve parks and sports fields for the city’s low-income school children. “Fair Play” highlighted the misplaced values of some corporate leaders and politicians. However, criticisms of Fiserv must be tempered somewhat because, like the MIP, the Fiserv builders did succeed in employing a large number of minority-owned businesses and unemployed and underemployed workers from Milwaukee’s low-income zip codes.

Norquist also tried, but failed, to raze another freeway (I-794) through downtown that connected to the Hoan Bridge. The Hoan Bridge was known as the “bridge to nowhere” as a result of efforts by residents to block I-794’s extension south of the bridge. However, during the 1990s, the municipal government completed a limited-access boulevard connecting the south side to the Hoan Bridge and downtown. South side residents then fought against the proposal to tear down I-794 as well as a later plan to destroy the Hoan Bridge because both provided quick access from the south to downtown.

Currently, after years of controversy the state is reviving a proposal to rebuild and widen a three-mile section of I-94 through central Milwaukee. Construction unions, along with local and suburban businesses, have lobbied heavily for adding lanes to the freeway, claiming that the sixty-year-old expressway is dangerous, congested, and that an expansion would create needed jobs. Republican suburban officials support the freeway’s expansion to better link the city to distant manufacturing and commercial areas. In 2017, Republican Governor Scott Walker scotched the project, in part by aligning with liberal Milwaukee activists, minority community leaders, environmental organizations, and the city’s common council and current Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett. Walker argued that transportation funds flowing to Milwaukee should instead be spent on roads in northern and rural Wisconsin, which solidified his support from areas outside the city.

More importantly, in 2017 Walker lobbied for a state “right to work” law, eventually passed by the legislature, that undermined unions. The construction unions responded by backing Walker’s Democratic challenger, Tony Evers, who won in 2018. Evers then promised more transportation funding and has indicated he supports the expansion of I-94 despite the opposition from Milwaukee’s politicians, environmentalists, and community organizers who only support reconstruction, but not expansion. This “fix it first” approach (reconstruction but not adding lanes) would save $200 million, which the opponents argue could be used for expanding mass transit to benefit the city’s non-drivers who need to commute to jobs located in the suburbs. Increased working from home during the pandemic has also undercut the argument for the freeway’s expansion. Finally, the memory of Bronzeville’s destruction motivates opponents of this project.

This brief history suggests that debates over freeways continue long after construction begins. Urban freeways require ongoing reconstruction and expansion that can have direct impacts on local communities. The memories of neighborhood ruination and freeway revolts of the 1960s and 1970s live on in many cities like Milwaukee. These memories help spur community action against freeway rebuilding and expansion. Central city communities resist freeway expansion and demand more mass transit for those who do not drive and cannot get to suburban jobs. But not all freeways are opposed, with some communities supporting the access they provide, as was the case on Milwaukee’s South Side.

This history also shows that states can and should do more to target the hiring of women and minorities, as happened on the Marquette Interchange reconstruction. Communities harmed by prior freeway construction should receive first consideration for any jobs related to all new construction projects.

Other entries in the Justice and the Interstates series:

- Sarah J. Peterson, “The Myth and the Truth about the Interstate.”

- Rebecca Retzlaff and Jocelyn Zanzot, “The Interstates Planned Violence and the Need for Truth and Reconciliation.”

- Danielle Wiggins, “Remembering Sweet Auburn Before the Expressway: What Nostalgia Reveals about the Limits of Postwar Liberalism“

- Kyle Shelton, “Right in the Way: Generations of Highway Impacts in Houston“

- Tierra Bills, “A Contemporary Path to Transportation Justice.”

- Amanda Phillips de Lucas, “The Perils of Participation.”

- Sarah Jo Peterson, “Justice and the Interstates: A Proposal for a National Project of Truth and Accountability.”

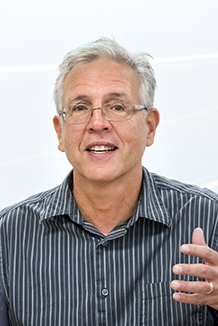

Dr. Ruben L. Anthony Jr. has been the President and CEO of the Urban League of Greater Madison since March of 2015. In the time he has been with the Urban League of Greater Madison, they have increased their job placements by 39 percent and have made over 1,400 placements. Over the past thirty years Dr. Anthony has been a senior manager in the public, private, and not profit sectors. He is a subject matter expert (SME) in developing job placement strategies and in minority business development. The majority (19 years) of his career has been as a manager with the Wisconsin Department of Transportation where he started as a first line supervisor and eventually became the Deputy Secretary and the Chief Operations Officer from 2003 to 2010. As the Deputy Secretary he managed 3,600 FTEs and an annual budget of $3.25 billion dollars. He was also responsible for managing the day to day operations of the agency and overseeing the programming of all areas. In 2017 he was awarded the Golden Champion Award by the National Association of Minority Contractors – Wisconsin Chapter for leadership in minority business development in the Wisconsin Construction Industry.

Joseph A. Rodriguez is Professor of History and Urban Studies and Chair in the Department of History at UW-Milwaukee where he teaches classes on U.S., Latinx, Asian American, and Urban History. He has written books and articles on those topics including the history of Latinos in Milwaukee. He gives frequent invited talks on the history of Latinos in the United States.

Featured image (at top): Aerial view of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Carol M. Highsmith, 2018, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

One thought on “Harnessing the Memory of Freeway Displacement in the Cream City”