[Editor’s note: In anticipation of UHA 2020 to be held in Detroit, October 8-11, 2020, The Metropole is featuring Detroit as our Metro of the Month for January. See here for the CFP and here for info about and link to the UHA spreadsheet. The latter is meant to help urbanists find prospective panels and panelists.]

Detroit does not lack for cinematic representation. The most recent example, the Kathryn Bigelow directed Detroit, depicted the urban rebellion of 1967 and the police brutality that helped spark the violent conflagration. Before that, perhaps the most notable contribution might be Steven Soderbergh’s adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s novel Out of Sight. The 1998 film followed the travails of George Clooney and Ving Rhames as two frustrated former convicts and thieves in search of one final score, with a relentless F.B.I. agent, played by Jennifer Lopez, in pursuit. Soderbergh managed to capture the city’s architectural past, its class- and race-based urban-suburban division, and its social geography amid a noirish Motor City tale of theft, sensuality, and brutality.

For more intrepid filmgoers, 1987’s Robocop succinctly captures the city’s plight and the arc of America more broadly in its tale of privatized police forces, neoliberal urban governance and corporate malfeasance expressing snide dismissiveness and satirical laughter simultaneously. “RoboCop ’87 is a biting indictment of neoliberal urbanism,” Keith Orejel wrote of the movie in 2014. “The central villain of the film is the Omni Consumer Products (OCP) corporation, whose maniacal plan is to bulldoze the slums (which seems to be most of the city) and build “Delta City,” a luxurious high-rise dominated community, over the rubble. It is urban redevelopment taken to its wildest extremes.” Sound familiar?

Regrettably, the exalted automobile that built Detroit would one day help undermine it as cars and highways funneled residents to suburban environs. In this way, the Motor City embodies the countervailing forces of twentieth century urbanity.

Yet one can become imprisoned by such depictions. As Rebecca J. Kinney argues in her 2016 book, Beautiful Wasteland: The Rise of Detroit as America’s Postindustrial Frontier, works that portray a city in debilitating crisis or as an empty frontier serve the forces of neoliberalism all too well. Presenting Detroit as “a beautiful wasteland,” she writes, presages its identification as a comeback city, ripe for new investment—systematic prejudices and failures be damned.

Popular histories frequently travel this road. Take Ze’ev Chafets’s Devil’s Night: And Other True Tales of Detroit, which turns 30 in 2020. “Detroit today is a genuinely fearsome-looking place,” he wrote in 1990. “Most of the neighborhoods appear to be the victims of bombardment—houses burned and vacant, buildings crumbling, whole city blocks overrun with weeds and the carcasses of discarded automobiles.” More recent additions, such as Charlie LeDuff’s Detroit: An American Autopsy (2013), and Mark Binelli’s Detroit City is the Place to Be: The Afterlife of an American Metropolis (2012), tend to represent the city in similar fashion, as an almost undead figure, bound to its industrial past in a zombie-like existence. “If we were to only survey the popular historiography of Detroit, we might conclude that Detroit is only interesting because of the 1967 riot and five decades of urban crisis,” writes historian Brandon Ward.

Though Detroit often suffers from nostalgic interpretations of its history that depend on a blinkered view of its recent past and present, it’s worth remembering that at the outset of the twentieth century, it was the cynosure of American technology. Henry Ford’s automobile empire placed it and its surrounding metropolitan region at the forefront of movement, both technological and human, as the era of modernism unfolded.

Between his innovative assembly lines and the elegant simplicity of his Model T, Ford’s vision aligned Detroit with modernist philosophy as espoused by Le Corbusier and others. “Cars, cars, fast, fast. One is seized, filled with enthusiasm, with joy … the joy of power,” wrote Le Corbusier in 1924. “One has confidence in this new society: it will find a magnificent expression of its power. One believes in it.”

Machines alone did not dominate movement in Detroit: great flows of humanity added to its perpetual motion. Immigrants from across the globe settled in the city and larger region to work in Ford’s plants (and those of his eventual competitors). For example, by 1920 one-fourth of Highland Park’s population had been born abroad. The Detroit area soon boasted the nation’s first mosque. Irish, Maltese, Mexican, Japanese, Syrian, and others worked together in the carefully and brutally-designed symmetry of automobile production. From 1910 to 1940, the population surrounding the famed River Rouge plant boomed from 17,960 to 158,416.

Ford’s plants drew tens of thousands of African Americans to metropolitan Detroit, particularly during the industrial booms brought on by the world wars. Many moved to suburbs near those plants, a development regrettably ignored by writers. “Historians have done a better job excluding African Americans from the suburbs than even their white suburbanites,” writes Andrew Weise in his book on African American suburbs, Places of Their Own: African American Suburbanization in the Twentieth Century.

Yet, “industrial suburbs” like those that grew near Ford’s River Rouge plant reveal new complexities about Detroit and the nation. A new study by Todd Michney and Ladale Winling reveals that black homeowners who worked in and resided near the plant received “considerable numbers of HOLC refinancing loans” between 1933-1935—what the two historians dub the “rescue phase” before the HOLC, FHA, and VA imposed more systematic segregation in what they call the “consolidation phase” spanning 1935-1951. Blacks established roots within Detroit as well, mostly on its East Side in communities such as Black Bottom and Paradise Valley, but also in West Side middle-class enclaves such as Conant Gardens and Tireman Alley. Those West Side residents, perhaps due to their middle-class status, secured more HOLC refinancing loans than did working-class peers in other parts of the city.

From the start of the twentieth century through the 1930s, a mix of Beaux Arts and Art Deco architecture rose throughout the city, again placing it at the vanguard of American culture. This too would have an ironic effect as it unwittingly established the future setting for “ruin porn” – captured perhaps most famously by Camillo Vergera, whose photographs preserved the city in dystopian amber.

World War II reshaped the larger metropolitan region. With the U.S.’s entry into the global conflict, 14 billion military dollars flowed into the city and its suburbs. Its population blossomed: while the city added only 30,000 new residents from April 1940 to June 1944, the the four suburban counties around Detroit and Willow Run added 200,000 more. Ypsilanti, Inkster, Ecorse Township, and Royal Oak Township provided newly arrived African Americans with their own suburban opportunities. Though infrastructure expansion initially failed to keep pace with this rapid growth, over time municipal and state governments established services and agencies that eventually reshaped suburban Detroit. Yet suburban opportunity remained restricted due to restrictive deeds and covenants dating back to the turn of the century, which produced levels of segregation equaled only by other highly-stratified metropolises such as Philadelphia and Atlanta.

Even in its heyday, Detroit’s cultural and economic achievements hid troubling developments. During World War II, as the city boomed, it was already bleeding manufacturing jobs to the South and West and, later, out of the country altogether. Meanwhile, the military spending that had reshaped metropolitan Detroit would be redirected to the coastal West and Sunbelt. Even as the sounds of Motown worked their way into the ears of Americans during the 1950s, black Detroiters suffered the harshest burdens imposed by this hemorrhaging of jobs and capital.

For Tom Sugrue, author of arguably the most influential history of Detroit published over the last three decades, the origins of the city’s crisis could be found not in the 1960s, but during the 1950s, when a more rigid form of segregation, aided by FHA and VA federal policies, took hold across the city. African-American job seekers encountered race-based barriers in securing employment, just as the first waves of deindustrialization hit the city. Whites who could afford to flee the city did; those that could not dug in their heels and deployed legal and extralegal means to keep African American residents in their place.

During this period, police tactics, procedures, and policies led to a troubling paradox: both harassment and under-policing of black communities became standard. By the end of the 1960s, black Detroiters abhorred the violence and crime that affected their neighborhoods, but feared police intervention almost as much. New programs such as the Detroit Police Department’s (DPD) STRESS (Stop Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets) program, begun in 1971, were little better. Disturbing numbers of African Americans died under the custody of STRESS.

Detroit faced very real challenges during and after the 1960s. From 1970 to 1980, over 300,000 residents abandoned the Michigan metropolis; by 1980, 20 percent of the city’s growing black population lived under the national poverty line. Infant mortality rose to nearly 25 percent. Many cities struggled with deindustrialization, but “but few suffered to the extent Detroit did,” notes historian Heather Ann Thompson.

Journalists such as Jim Sleeper, Frederick Siegel, and Jonathan Rieder placed Detroit’s decline squarely at the feet of its black residents, who, they argued, forced whites to leave when they turned to a more militant brand of politics. Yet those authors failed to acknowledge how fear of crime and the decline of property values sparked white flight. Thompson rightly notes that such arguments ignore how a history of systematic discrimination from housing, occupational segregation, and police brutality had not only shaped city politics and dynamics but informed the black community’s embrace of a more militant strain of politics which alienated erstwhile white liberals and conservatives alike. Were all white Detroiters racists? Of course not, writes Thompson, but many refused to acknowledge the structural factors that had contributed to the city’s state of affairs and, by extension, privileged them over their black counterparts.

Judging from the bibliography provided below, the city has inspired numerous influential works over the past thirty years—and its history has revealed much about the United States at large. Sugrue’s The Origins of the Urban Crisis sought to explain the complexities of not only Detroit’s crisis, but the crises of cities across the nation. Detroit became a harbinger for national urban decline.

Judging from the bibliography provided below, the city has inspired numerous influential works over the past thirty years—and its history has revealed much about the United States at large. Sugrue’s The Origins of the Urban Crisis sought to explain the complexities of not only Detroit’s crisis, but the crises of cities across the nation. Detroit became a harbinger for national urban decline.

Where does that leave urban historians of Detroit today? With the dawn of the twenty-first century, historians such as Thompson, Stephen M. Ward, and Victoria Wolcott have shifted the focus away from how and why whites fled to how African Americans, men and women, hacked it out in the Motor City, making lives for themselves and their fellow residents while also keeping the city breathing. This is not to say the actions and policies of white Detroiters and their suburban counterparts have gone ignored. In his 2007 work Colored Property, David Freund stalked the suburbs of Detroit, exploring how integral the racialization of federal and state policies were to white homeownership and the damaging effects of naturalizing these kind of discriminatory government programs. And even more recent work by George Galster, Ward, Kinney, and Kimberly Kinder attempt to reorient how we see the city.

Unfortunately, even with an improved awareness of the city’s history, certain tropes persist. For example, the media has often portrayed practices like “urban homesteading” and “self provisioning” as valuable updates to the tradition of American bootstrapping while ignoring the systematic forces that make it necessary. In fact, historians such as Kinder and Kinney suggest that “self-provisioning,” or what Kinder describes as “devolved urban governance,” is little more than neoliberal governance run amok. “I do not pretend that self- provisioning will ‘save’ Detroit,” she writes.

Where does this leave us? As Joe Casey, lead singer of Detroit postpunk band Protomartyr sings on its 2015 album, The Agent Intellect, “The proof we are here, is the dust that they’re breathing, the proof we’re apart, is the fact they’re still living, they don’t see us.” Casey is pointing both to the importance of locals keeping the city alive and the media’s refusal to acknowledge them. The band’s first three albums emphasize the fact that while Detroit’s existence remains tenuous, the city and its residents persist. Nor is the band unaware of the “Motor City rediscovered” trope so present in popular narratives. “Have you heard the bad news, we’ve been saved by both coasts,” Casey sings on “Come and See,” from the 2014 album Under Color of Official Right, “a bag of snakes with heads of gas, the complicated hair cuts ride in on white asses.” “Smug urban settlers,” “bad bartenders,” and “upper-class slummers,” among numerous others, come in for criticism on “Tarpeian Rock,” off the same album. Even amid struggle—or maybe even because of it—Detroit has birthed punk pioneers like MC5 and Iggy Pop and the Stooges. Resiliency stands as a hallmark of Detroit and its denizens. Urban historians more than anyone know this. Here’s to hoping that new works carrying this message break through.

Much thanks to University of Buffalo’s Victoria Wolcott for her help with the bibliography and especially historian Tom Klug, who has compiled a vast and very comprehensive list of works exploring Detroit from which this bibliography is derived. You can find our curated version below – which it should be noted leans heavily on publications from 1990 forward with a few works from the 1980s thrown in as well. We encourage readers to dig into Klug’s move expansive list, particularly for scholarship published prior to 1980, which can be found here.

Bibliography

Aberbach, Joel D., and Jack L. Walker. Race in the City: Political Trust and Public Policy in the New Urban System. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1973.

Abonyi, Malvina Hauk, and James A. Anderson. Hungarians of Detroit. Peopling of Michigan. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University, Center for Urban Studies, 1977.

Abraham, Nabeel. “Detroit’s Yemeni Workers.” MERIP Reports, no. 57 (May 1977): 3–9. https://doi.org/10.2307/3011555.

Abraham, Nabeel, Sally Howell, and Andrew Shryock, eds. Arab Detroit 9/11: Life in the Terror Decade. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2011.

Abrahamson, Michael. “‘Actual Center of Detroit’: Method, Management, and Decentralization in Albert Kahn’s General Motors Building.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 77, no. 1 (March 2018): 56–76. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2018.77.1.56.

Abt, Jeffrey. A Museum on the Verge: A Socioeconomic History of the Detroit Institute of Arts, 1882-2000. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2001.

Adhya, Anirban. “From Crisis to Projects; a Regional Agenda for Addressing Foreclosures in Shrinking First Suburbs: Lessons from Warren, Michigan.” Urban Design International 18, no. 1 (January 2013): 43–60. https://doi.org/10.1057/udi.2012.31.

———. Shrinking Cities and First Suburbs: The Case of Detroit and Warren, Michigan. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Adler, Richard. Cholera in Detroit: A History. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2013.

Akhtar, Saima. “Immigrant Island Cities in Industrial Detroit.” Journal of Urban History 41, no. 2 (March 2015): 175–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144214563509.

Amsterdam, Daniel. Roaring Metropolis: Businessmen’s Campaign for a Civic Welfare State. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Anastakis, Dimitry. “From Independence to Integration: The Corporate Evolution of the Ford Motor Company of Canada, 1904–2004.” Business History Review 78, no. 2 (Summer 2004): 213–53. https://doi.org/10.2307/25096866.

Anderson, Carlotta R. All-American Anarchist: Joseph A. Labadie and the Labor Movement. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1998.

Anderson, Janet. Island in the City: Belle Isle, Detroit’s Beautiful Island: How Belle Isle Changed Detroit Forever. Detroit, MI: Friends of Belle Isle, 2001.

Anderson, Karen Tucker. “Last Hired, First Fired: Black Women Workers during World War II.” The Journal of American History 69, no. 1 (June 1982): 82–97. https://doi.org/10.2307/1887753.

Apel, Dora. Beautiful Terrible Ruins: Detroit and the Anxiety of Decline. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2015.

Archer, Melanie. “Small Capitalism and Middle-Class Formation in Industrializing Detroit, 1880-1900.” Journal of Urban History 21, no. 2 (January 1995): 218–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/009614429502100203.

Arnold, Amy L., and Brian D. Conway. Michigan Modern: Design That Shaped America. Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith, 2016.

Ashworth, William. The Late, Great Lakes: An Environmental History. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1987.

Athans, Mary Christine. “A New Perspective on Father Charles E. Coughlin.” Church History 56, no. 2 (June 1987): 224–35. https://doi.org/10.2307/3165504.

Atleson, James B. Labor and the Wartime State: Labor Relations and Law During World War II. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

Aubert, Danielle, Lana Cavar, and Natasha Chandani, eds. Thanks for the View, Mr. Mies: Lafayette Park, Detroit. New York, NY: Metropolis Books, 2012.

Austin, Dan. Lost Detroit: Stories Behind the Motor City’s Majestic Ruins. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2010.

Ayers, Oliver. Laboured Protest: Black Civil Rights in New York City and Detroit During the New Deal and Second World War. New York, NY: Routledge, 2019.

Baba, Marietta L., and Malvina Hauk Abonyi. Mexicans of Detroit. Peopling of Michigan Series. Detroit, MI: Ethnic Studies, Center for Urban Studies, Wayne State University, 1979.

Babson, Steve. Building the Union: Skilled Workers and Anglo-Gaelic Immigrants in the Rise of the UAW. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1991

Babson, Steve, Dave Riddle, and David Elsila. The Color of Law: Ernie Goodman, Detroit, and the Struggle for Labor and Civil Rights. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2010.

Bachelor, Lynn W. “Evaluating the Implementation of Economic Development Policy: Lessons from Detroit’s Central Industrial Park Project.” Review of Policy Research 4, no. 4 (May 1985): 601–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1541-1338.1985.tb00308.x.

———. “Regime Maintenance, Solution Sets, and Urban Economic Development.” Urban Affairs Quarterly 29, no. 4 (June 1994): 596–616. https://doi.org/10.1177/004208169402900405.

Bailey, E. J. “Health Care Use Patterns Among Detroit African Americans: 1910-1939.” Journal of the National Medical Association 82, no. 10 (October 1990): 721–23.

Baime, A. J. The Arsenal of Democracy: FDR, Detroit, and an Epic Quest to Arm an America at War. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014.

Bak, Richard. A Place for Summer: A Narrative History of Tiger Stadium. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1998.

———. Boneyards: Detroit Under Ground. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2010.

———. Detroit: A Postcard History. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 1998.

Balderrama, Francisco E., and Raymond Rodriguez. Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press, 2006.

Baldwin, Neil. Henry Ford and the Jews: The Mass Production of Hate. New York, NY: Public Affairs, 2001.

Barnard, John. American Vanguard: The United Auto Workers During the Reuther Years, 1935- 1970. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2004.

Barrow, Heather B. Henry Ford’s Plan for the American Suburb: Dearborn and Detroit. DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 2015.

Batchelor, Ray. Henry Ford, Mass Production, Modernism, and Design. New York, NY: Manchester University Press, 1994.

Bates, Beth Tompkins. The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

Bavery, Ashley Johnson. “‘Crashing America’s Back Gate’: Illegal Europeans, Policing, and Welfare in Industrial Detroit, 1921-1939.” Journal of Urban History 44, no. 2 (March 2018): 239–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144216655791.

Bego, Mark. Aretha Franklin: The Queen of Soul. New York, NY: Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., 2012.

Bentley, George C., Priscilla McCutcheon, Robert G. Cromley, and Dean M. Hanink. “Race, Class, Unemployment, and Housing Vacancies in Detroit: An Empirical Analysis.” Urban Geography 37, no. 5 (July 2016): 785–800. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1112642.

Benz, Terressa A. “Toxic Cities: Neoliberalism and Environmental Racism in Flint and Detroit Michigan.” Critical Sociology 45, no. 1 (January 2019): 49–62.

Berman, Lila Corwin. “Jewish Urban Politics in the City and Beyond.” Journal of American History 99, no. 2 (September 2012): 492–519. https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jas260.

———. Metropolitan Jews: Politics, Race, and Religion in Postwar Detroit. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Biles, Roger. “Expressways before the Interstates: The Case of Detroit, 1945–1956.” Journal of Urban History 40, no. 5 (September 2014): 843–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144214533294.

Binelli, Mark. Detroit City Is the Place to Be: The Afterlife of an American Metropolis. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books, 2012.

Bjorn, Lars, and Jim Gallert. Before Motown: A History of Jazz in Detroit, 1920-60. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2001.

Bledsoe, Timothy, Michael Combs, Lee Sigelman, and Susan Welch. “Trends in Racial Attitudes in Detroit, 1968-1992.” Urban Affairs Review 31, no. 4 (March 1996): 508–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/107808749603100404.

Blum, Peter H. Brewed in Detroit: Breweries and Beers Since 1830. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1999.

Bockmeyer, Janice L. “A Culture of Distrust: The Impact of Local Political Culture on Participation in the Detroit EZ.” Urban Studies 37, no. 13 (December 2000): 2417–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980020080621.

Boggs, James. Pages from a Black Radical’s Notebook: A James Boggs Reader. Edited by Stephen M. Ward. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2011.

———. The American Revolution: Pages from a Negro Worker’s Notebook. New York, NY: Monthly Review Press, 2009.

Bogue, Margaret Beattie. Fishing the Great Lakes: An Environmental History, 1783–1933. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2000.

Bolkosky, Sidney M. Harmony & Dissonance: Voices of Jewish Identity in Detroit, 1914-1967. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1991.

Bomey, Nathan. Detroit Resurrected: To Bankruptcy and Back. New York, NY: W.W. Norton Company, 2017.

Boone, Lauren, Lizz Ultee, Ed Waisanen, Joshua P. Newell, Joshua A. Thorne, and Rebecca Hardin. “Collaborative Creation and Implementation of a Michigan Sustainability Case 11 on Urban Farming in Detroit.” Case Studies in the Environment, August 2018. https://doi.org/10.1525/cse.2017.000703.

Bostick, Alice J. The Roots of Inkster. Inkster, MI: Inkster Public Library and Historical Commission, 1980.

Boyd, Herb. Black Detroit: A People’s History of Self-Determination. New York, NY: Harper Collins, 2017.

Boyd, Melba Joyce. Wrestling with the Muse: Dudley Randall and the Broadside Press. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2003.

Boyd, Melba Joyce, and M. L. Liebler. Abandon Automobile: Detroit City Poetry 2001. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2001.

Boyle, Kevin. Arc of Justice: A Saga of Race, Civil Rights, and Murder in the Jazz Age. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, 2004.

Bradley, Betsy Hunter. The Works: The Industrial Architecture of the United States. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Brinkley, Alan. Voices of Protest: Huey Long, Father Coughlin, & the Great Depression. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 1982.

Brinkley, Douglas. Wheels for the World: Henry Ford, His Company, and a Century of Progress, 1903-2003. New York, NY: Viking, 2003.

Bryan, Ford R. Beyond the Model T: The Other Ventures of Henry Ford. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1997.

Burns, Andrea A. “Waging Cold War in a Model City: The Investigation of ‘Subversive’ Influences in the 1967 Detroit Riot.” Michigan Historical Review 30, no. 1 (Spring 2004): 3–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/20174058.

Byrnes, Mary E. “A City Within a City: A ‘Snapshot’ of Aging in a HUD 202 in Detroit, Michigan.” Journal of Aging Studies 25, no. 3 (August 2011): 253–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.011.

Camp, Jordan T. “Challenging the Terms of Order: Representations of the Detroit Rebellions, 1967–1968.” Kalfou 2, no. 1 (Spring 2015): 161–80. https://doi.org/10.15367/kf.v2i1.61.

Capeci, Dominic J. Race Relations in Wartime Detroit: The Sojourner Truth Housing Controversy of 1942. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1984.

Capeci, Dominic J., and Martha Wilkerson. Layered Violence: The Detroit Rioters of 1943. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 1991.

Carew, Anthony. Walter Reuther. New York, NY: Manchester University Press, 1993.

Carriere, Michael H. “Touch and Go Records and the Rise of Hardcore Punk in Late Twentieth- Century Detroit.” Cultural History 4, no. 1 (March 2015): 19–41. https://doi.org/10.3366/cult.2015.0082.

Chafets, Ze’ev. Devil’s Night: And Other True Tales of Detroit. New York, NY: Vintage Books, 1990.

Christensen, Dana May. “Securing the Momentum: Could a Homestead Act Help Sustain Detroit Urban Agriculture.” Drake Journal of Agricultural Law 16 (2011): 241–60.

Ciani, Kyle E. “Hidden Laborers: Female Day Workers in Detroit, 1870–1920.” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 4, no. 1 (January 2005): 23–51. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537781400003649.

Clark, Daniel J. Disruption in Detroit: Autoworkers and the Elusive Postwar Boom. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2018.

Clemens, Elizabeth. The Works Progress Administration in Detroit. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008.

Colasanti, Kathryn J. A., Michael W. Hamm, and Charlotte M. Litjens. “The City as an ‘Agricultural Powerhouse’? Perspectives on Expanding Urban Agriculture from Detroit, Michigan.” Urban Geography 33, no. 3 (April 2012): 348–69. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.33.3.348.

Collum, Marla O., Barbara E. Krueger, and Dorothy Kostuch, eds. Detroit’s Historic Places of Worship. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2012.

Conant Gardeners. Conant Gardens: A Black Urban Community, 1925-1950. Detroit, MI: The Conant Gardeners, 2001.

Coopey, Richard, and Alan McKinlay. “Power Without Knowledge? Foucault and Fordism, C.1900–50.” Labor History 51, no. 1 (2010): 107–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/00236561003654800.

Cowie, Jefferson. “‘A One-Sided Class War’: Rethinking Doug Fraser’s 1978 Resignation from the Labor-Management Group.” Labor History 44, no. 3 (August 2003): 307–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/002365603200012928.

Cox, Norman. Detroit’s New Front Porch: A Riverfront Greenway in Southwest Detroit. Washington, D.C.: Rails-To-Trails Conservancy, 1999.

Cruz, John. Metro Detroit’s Foreign-Born Population. Detroit, MI: Global Detroit Initiative, 2014.

Danziger, Edmund Jefferson. Survival and Regeneration: Detroit’s American Indian Community. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1991.

Darden, Joe T. “Black Residential Segregation Since the 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer Decision.” Journal of Black Studies 25, no. 6 (July 1995): 680–91.

Darden, Joe T., Ron Malega, and Rebecca Stallings. “Social and Economic Consequences of Black Residential Segregation by Neighbourhood Socioeconomic Characteristics: The Case of Metropolitan Detroit.” Urban Studies 56, no. 1 (January 2019): 115–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018779493.

Darden, Joe T., and Richard W. Thomas. Detroit: Race Riots, Racial Conflicts, and Efforts to Bridge the Racial Divide. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2013.

Desjarlais, Mary, and Bill Rauhauser. Beauty on the Streets of Detroit: A History of the Housing Market in Detroit. 2nd ed. Ferndale, MI: Cambourne Pub., 2011. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360608976737.

Dewar, Margaret, Eric Seymour, and Oana Druță. “Disinvesting in the City: The Role of Tax Foreclosure in Detroit.” Urban Affairs Review 51, no. 5 (September 2015): 587–615. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087414551717.

Doody, Colleen. Detroit’s Cold War: The Origins of Postwar Conservatism. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Downey, Liam. “Environmental Racial Inequality in Detroit.” Social Forces 85, no. 2 (December 2006): 771–96. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2007.0003.

Downs, Linda Bank. Diego Rivera: The Detroit Industry Murals. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1999.

Eisinger, Peter. “Detroit Futures: Can the City Be Reimagined?” City & Community 14, no. 2 (June 2015): 106–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12109.

———. “Is Detroit Dead?” Journal of Urban Affairs 36, no. 1 (February 2014): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12071.

Esch, Elizabeth. The Color Line and the Assembly Line: Managing Race in the Ford Empire. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2018.

Fahey, Carolyn. “Urban or Moral Decay?: The Case of Twentieth Century Detroit.” Journal of Architecture and Urbanism 41, no. 3 (July 2017): 170–83. https://doi.org/10.3846/20297955.2017.1301292.

Fehr, Russell MacKenzie. “Political Protestantism: The Detroit Citizens League and the Rise of the Ku Klux Klan.” Journal of Urban History 45, no. 6 (2018): 1153-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144218793646.

Freund, David M. P. Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2010.

Fu, May C. “On Contradiction: Theory and Transformation in Detroit’s Asian Political Alliance.” Amerasia Journal 35, no. 2 (January 2009): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.17953/amer.35.2.fq15578270gr4411.

Gabin, Nancy F. Feminism in the Labor Movement: Women and the United Auto Workers, 1935- 1975. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1990.

Gallagher, John. Reimagining Detroit: Opportunities for Redefining an American City. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2010.

Galster, George. “A Structural Diagnosis and Prescription for Detroit’s Fiscal Crisis: Response to William Tabb’s ‘If Detroit Is Dead, Some Things Need to Be Said at the Funeral.’” Journal of Urban Affairs 37, no. 1 (2015): 17–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/juaf.12175.

———. Driving Detroit: The Quest for Respect in the Motor City. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012.

Gansky, Andrew Emil. “‘Ruin Porn’ and the Ambivalence of Decline: Andrew Moore’s Photographs of Detroit.” Photography and Culture 7, no. 2 (July 2014): 119–39. https://doi.org/10.2752/175145214X13999922103084.

Goldberg, David. “Community Control of Construction, Independent Unionism, and the ‘Short Black Power Movement’ in Detroit.” In Black Power at Work: Community Control, Affirmative Action, and the Construction Industry, edited by David Goldberg and Trevor Griffey, 90–111. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2010.

Goodall, Alex. “The Battle of Detroit and Anti-Communism in the Depression Era.” The Historical Journal 51, no. 2 (June 2008): 457–80. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0018246X0800678X.

Grieveson, Lee. “The Work of Film in the Age of Fordist Mechanization.” Cinema Journal 51, no. 3 (Spring 2012): 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1353/cj.2012.0042.

Halpern, Martin. “‘I’m Fighting for Freedom’: Coleman Young, HUAC, and the Detroit African American Community.” Journal of American Ethnic History 17, no. 1 (Fall 1997): 19– 38.

Hamera, Judith. Unfinished Business: Michael Jackson, Detroit, and the Figural Economy of American Deindustrialization. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2017.

Hamlin, Michael. A Black Revolutionary’s Life in Labor: Black Workers Power in Detroit. Detroit, MI: Against the Tide Books, 2013.

Hauser, Michael, and Marianne Weldon. Twentieth Century Retailing in Downtown Detroit. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2008.

Herman, Max Arthur. Summer of Rage: An Oral History of the 1967 Newark and Detroit Riots. New York, NY: Peter Lang, 2017.

Herron, Jerry. AfterCulture: Detroit and the Humiliation of History. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 1993.

———. “Borderland/Borderama/Detroit: Part 1.” Places Journal, July 2010. https://doi.org/10.22269/100706.

———. “Borderland/Borderama/Detroit: Part 2.” Places Journal, July 2010. https://doi.org/10.22269/100707.

———. “Borderland/Borderama/Detroit: Part 3.” Places Journal, July 2010. https://doi.org/10.22269/100708.

Hersey, John. The Algiers Motel Incident. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998.

Herstad, Kaeleigh. “‘Reclaiming’ Detroit: Demolition and Deconstruction in the Motor City.” The Public Historian 39, no. 4 (November 2017): 85–113. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2017.39.4.85.

High, Steven. “The Emotional Fallout of Deindustrialization in Detroit.” Labor: Studies in Working-Class History 16, no. 1 (March 2019): 127–49.

Highsmith, Andrew R. “Beyond Corporate Abandonment: General Motors and the Politics of Metropolitan Capitalism in Flint, Michigan.” Journal of Urban History 40, no. 1 (January 2014): 31–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144213508080.

———. Demolition Means Progress: Flint, Michigan, and the Fate of the American Metropolis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2015.

———. “Demolition Means Progress: Urban Renewal, Local Politics, and State-Sanctioned Ghetto Formation in Flint, Michigan.” Journal of Urban History 35, no. 3 (March 2009): 348–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144208330403. https://doi.org/10.2307/988576.

Hill, Alex B. “Critical Inquiry into Detroit’s ‘Food Desert’ Metaphor.” Food and Foodways 25, no. 3 (July 2017): 228–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710.2017.1348112.

Hill, Richard Child, and Joe R. Feagin. “Detroit and Houston: Two Cities in Global Perspective.” In The Capitalist City: Global Restructuring, and Community Politics, edited by Michael Smith and Joe R. Feagin, 155–77. New York, NY: Basil Blackwell, 1987.

Hill, Richard Child, and Cynthia Negrey. “Deindustrialization in the Great Lakes.” Urban Affairs Quarterly 22, no. 4 (June 1987): 580–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/004208168702200407.

Hine, Darlene Clark. “Black Migration to the Urban Midwest: The Gender Dimension, 1915- 1945.” In The Great Migration in Historical Perspectives, edited by Joe W. Trotter, 127– 46. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1991.

Hinton, Elizabeth Kai. “The Black Bolsheviks.” In The New Black History: Revisiting the Second Reconstruction, edited by Manning Marable and Elizabeth Kai Hinton, 211–28. The Critical Black Studies Series. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230338043_13.

Hooker, Clarence. Life in the Shadows of the Crystal Palace, 1910-1927: Ford Workers in the Model T Era. Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Press, 1997.

Hotton, Randy, and Michael W.R. Davis. Willow Run. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2016.

Howell, Sally. Old Islam in Detroit: Rediscovering the Muslim American Past. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Howell, Sally, and Andrew Shryock. “Cracking Down on Diaspora: Arab Detroit and America’s ‘War on Terror.’” Anthropological Quarterly 76, no. 3 (Summer 2003): 443–62. https://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2003.0040.

Hyde, Charles K. Arsenal of Democracy: The American Automobile Industry in World War II. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2013.

———. “The Dodge Brothers, the Automobile Industry, and Detroit Society in the Early Twentieth Century.” Michigan Historical Review 22, no. 2 (Fall 1996): 48–82. https://doi.org/10.2307/20173586.

———. The Dodge Brothers: The Men, the Motor Cars, and the Legacy. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2005.

Jacob, Mary Jane, and Linda Downs. The Rouge: The Image of Industry in the Art of Charles Sheeler and Diego Rivera. Detroit, MI: Detroit Institute of Arts, 1978.

Jacobs, A. J. “Embedded Autonomy and Uneven Metropolitan Development: A Comparison of the Detroit and Nagoya Auto Regions, 1969-2000.” Urban Studies 40, no. 2 (February 2003): 335–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980220080301.

Jeansonne, Glen. Gerald L. K. Smith: Minister of Hate. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1997.

———. “The Priest and the President: Father Coughlin, FDR, and 1930s America.” The Midwest Quarterly 53, no. 4 (Summer 2012): 359-373.

Jefferys, Steve. Management and Managed: Fifty Years of Crisis at Chrysler. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1986.

Johnson, Marilynn S. “Gender, Race, and Rumours: Re-Examining the 1943 Race Riots.” Gender & History 10, no. 2 (July 1998): 252–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468- 0424.00099.

Jung, Yuson, and Andrew Newman. “An Edible Moral Economy in the Motor City: Food Politics and Urban Governance in Detroit.” Gastronomica: The Journal of Critical Food Studies 14, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1525/gfc.2014.14.1.23.

Kaplan, Richard. “The Economics of Popular Journalism in the Gilded Age: The Detroit Evening News in 1873 and 1888.” Journalism History 21, no. 2 (Summer 1995): 65–78.

Karibo, Holly M. Sin City North: Sex, Drugs, and Citizenship in the Detroit-Windsor Borderland. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Kenyon, Amy Maria. Dreaming Suburbia: Detroit and the Production of Postwar Space and Culture. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2004.

Kickert, Conrad, and Rainer vom Hofe. “Critical Mass Matters: The Long-Term Benefits of Retail Agglomeration for Establishment Survival in Downtown Detroit and The Hague.” Urban Studies 55, no. 5 (April 2018): 1033–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017694131.

Kinder, Kimberley. DIY Detroit: Making Do in a City without Services. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

King, Athena, Todd Shaw, and Lester K. Spence. “Hype, Hip-Hop, and Heartbreak: The Rise and Fall of Kwame Kilpatrick.” In Whose Black Politics: Cases in Post-Racial Black Politics, edited by Andra Gillespie, 105–30. New York, NY: Routledge, 2010.

Kinney, Rebecca J. Beautiful Wasteland: The Rise of Detroit as America’s Postindustrial Frontier. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Kirkpatrick, L. Owen. “Urban Triage, City Systems, and the Remnants of Community: Some ‘Sticky’ Complications in the Greening of Detroit.” Journal of Urban History 41, no. 2 (March 2015): 261–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144214563503.

Klier, Thomas, and James M. Rubenstein. “Detroit Back from the Brink? Auto Industry Crisis and Restructuring, 2008-11.” Economic Perspectives 36, no. 2 (2012).

Klug, Thomas A. “100 Years of Advocacy, Service, and Excellence: A History of the American Society of Employers (Employers’ Association of Detroit).” Detroit, MI: American Society of Employers, 2002.

———. “Residents by Day, Visitors by Night: The Origins of the Alien Commuter on the U.S.-Canadian Border during the 1920s.” Michigan Historical Review 34, no. 2 (Fall 2008): 75–98.

———. “The Deindustrialization of Detroit.” In Detroit 1967: Origins, Impacts, Legacies, edited by Joel Stone, 65–75. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2017.

Knowles, Scott G., and Stuart W. Leslie. “‘Industrial Versailles’: Eero Saarinen’s Corporate Campuses for GM, IBM, and AT&T.” Isis 92, no. 1 (March 2001): 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1086/385038.

Kopytek, Bruce Allen. Crowley’s: Detroit’s Friendly Store. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2015.

Kornberg, Dana. “The Structural Origins of Territorial Stigma: Water and Racial Politics in Metropolitan Detroit, 1950s–2010s.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40, no. 2 (March 2016): 263–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12343.

Kramer, Michael J. “‘Can’t Forget the Motor City’: CREEM Magazine, Rock Music, Detroit Identity, Mass Consumerism, and the Counterculture.” Michigan Historical Review 28, no. 2 (Fall 2002): 42–77. https://doi.org/10.2307/20173983.

Kurashige, Scott. The Fifty-Year Rebellion: How the U.S. Political Crisis Began in Detroit. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2017.

Kusmer, Kenneth L. “African Americans in the City Since World War II: From the Industrial to the Post-Industrial Era.” Journal of Urban History 21, no. 4 (May 1995): 458–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/009614429502100403.

Langlois, Janet L. “‘Celebrating Arabs’: Tracing Legend and Rumor Labyrinths in Post-9/11 Detroit.” Journal of American Folklore 118, no. 468 (Spring 2005): 219–36. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaf.2005.0021.

———. Serving Children Then and Now: An Oral History of Early Childhood Education and Day Care in Metropolitan Detroit. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University, Center for Urban Studies, 1989.

Levering, Marijean. Detroit on Stage: The Players Club, 1910-2005. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2017.

Levin-Waldman, Oren M. The Political Economy of the Living Wage: A Study of Four Cities. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2005.

Lewis-Colman, David M. Race Against Liberalism: Black Workers and the UAW in Detroit. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Lichtenstein, Nelson. Labor’s War At Home: The CIO In World War II. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2003.

Locke, Hubert G. The Detroit Riot of 1967. 2nd ed. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2017.

Long, J. C. Roy D. Chapin: The Man Behind the Hudson Motor Car Company. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2004.

Macías, Anthony. “‘Detroit Was Heavy’: Modern Jazz, Bebop, and African American Expressive Culture.” The Journal of African American History 95, no. 1 (2010): 44–70.

Maraniss, David. Once in a Great City: A Detroit Story. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster, 2015.

Martelle, Scott. Detroit: A Biography. Chicago, IL: Chicago Review Press, 2012.

Martin, Brian. The Detroit Wolverines: The Rise and Wreck of a National League Champion, 1881–1888. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2018.

Meister, Chris. “Albert Kahn’s Partners in Industrial Architecture.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 72, no. 1 (March 2013): 78–95. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2013.72.1.78.

Miller, Karen R. Managing Inequality: Northern Racial Liberalism in Interwar Detroit. New York, NY: New York University Press, 2015.

Milloy, Jeremy. Blood, Sweat, and Fear: Violence at Work in the North American Auto Industry, 1960-1980. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Mirel, Jeffrey. The Rise and Fall of an Urban School System: Detroit, 1907-81. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1999.

Nawrocki, Dennis Alan, and David Clements. Art in Detroit Public Places. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2008.

Neill, William J. V. “Carry on Shrinking? The Bankruptcy of Urban Policy in Detroit.” Planning Practice & Research 30, no. 1 (January 2015): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697459.2014.997462.

Oestreicher, Richard Jules. Solidarity and Fragmentation: Working People and Class Consciousness in Detroit, 1875-1900. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

Peterson, Sarah Jo. Planning the Home Front: Building Bombers and Communities at Willow Run. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Pizzolato, Nicola. Challenging Global Capitalism: Labor Migration, Radical Struggle, and Urban Change in Detroit and Turin. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Poremba, David Lee, ed. Detroit in Its World Setting: A Three Hundred Year Chronology, 1701- 2001. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2001.

Pothukuchi, Kameshwari. “Bringing Fresh Produce to Corner Stores in Declining Neighborhoods: Reflections from Detroit FRESH.” Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 7, no. 1 (2016): 113–34. https://doi.org/10.5304/jafscd.2016.071.013.

———. “Five Decades of Community Food Planning in Detroit: City and Grassroots, Growth and Equity.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 35, no. 4 (2015): 419–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X15586630.

———. “‘To Allow Farming Is to Give up on the City’: Political Anxieties Related to the Disposition of Vacant Land for Urban Agriculture in Detroit.” Journal of Urban Affairs 39, no. 8 (2017): 1169–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2017.1319239.

Pratt, Henry J. Churches and Urban Government in Detroit and New York, 1895-1994. Detroit, Mich.: Wayne State University Press, 2004.

Rabinowitz, Matilda. Immigrant Girl, Radical Woman: A Memoir from the Early Twentieth Century. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2017.

Radelet, Joseph. “Stillness at Detroit’s Racial Divide: A Perspective on Detroit’s School Desegregation Court Order—1970–1989.” The Urban Review 23, no. 3 (September 1991): 173–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01108427.

Radzialowski, Thaddeus C. Polish Americans in the Detroit Area. Orchard Lake, MI: St. Mary’s College, 2001.

Rahman, Ahmad A. “Marching Blind: The Rise and Fall of the Black Panther Party in Detroit.” In Liberated Territory: Untold Local Perspectives on the Black Panther Party, edited by Yohuru Williams and Jama Lazerow, 181–231. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2008.

Rector, Josiah. “Environmental Justice at Work: The UAW, the War on Cancer, and the Right to Equal Protection from Toxic Hazards in Postwar America.” Journal of American History 101, no. 2 (September 2014): 480–502. https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jau380.

Reid, John B. “‘A Career to Build, a People to Serve, a Purpose to Accomplish’: Race, Class, Gender, and Detroit’s First Black Women Teachers, 1865-1916.” The Michigan Historical Review, 1992, 1–27.

Retzloff, Tim. “‘Seer or Queer?’ Postwar Fascination with Detroit’s Prophet Jones.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 8, no. 3 (2002): 271–96.

Rhomberg, Chris. The Broken Table: The Detroit Newspaper Strike and the State of American Labor. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2012.

Ribowsky, Mark. The Supremes: A Saga of Motown Dreams, Success, and Betrayal. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2009.

Rich, Wilbur C. Black Mayors and School Politics: The Failure of Reform in Detroit, Gary, and Newark. New York, NY: Garland, 1996.

Roberts, David. In the Shadow of Detroit: Gordon M. McGregor, Ford of Canada, and Motoropolis. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2006.

Robinson, Julia Marie. Race, Religion, and the Pulpit: Rev. Robert L. Bradby and the Making of Urban Detroit. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2015.

Rose, Daniel J. “Women’s Knowledge and Experiences Obtaining Food in Low-Income Detroit Neighborhoods.” In Women Redefining the Experience of Food Insecurity: Life Off the Edge of the Table, edited by Janet Page-Reeves, 145–66. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014.

Ryan, Brent D., and Daniel Campo. “Autopia’s End: The Decline and Fall of Detroit’s Automotive Manufacturing Landscape.” Journal of Planning History 12, no. 2 (May 2013): 95–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513212471166.

Safransky, Sara. “Greening the Urban Frontier: Race, Property, and Resettlement in Detroit.” Geoforum 56 (September 2014): 237–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2014.06.003.

Salvatore, Nick. Singing in a Strange Land: C. L. Franklin, the Black Church, and the Transformation of America. New York, NY: Little, Brown and Co., 2005.

Savaglio, Paula. “Big-Band, Slovenian-American, Rock, and Country Music: Cross-Cultural Influences in the Detroit Polonia.” Polish American Studies 54, no. 2 (Autumn 1997): 23–44.

Schindler, Seth. “Detroit After Bankruptcy: A Case of Degrowth Machine Politics.” Urban Studies 53, no. 4 (March 2016): 818–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014563485.

Shockley, Megan Taylor. “We, Too, Are Americans”: African American Women in Detroit and Richmond, 1940-54. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

Skendzel, Eduard Adam. Detroit’s Pioneer Mexicans: A Historical Study of the Mexican Colony in Detroit. Grand Rapids, MI: Littleshield Press, 1980.

Smith, Michael G. Designing Detroit: Wirt Rowland and the Rise of Modern American Architecture. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2017.

Smith, Michael O. “The City as State: Franchises, Politics, and Transit Development in Detroit, 1863-1879.” Michigan Historical Review 23, no. 1 (Spring 1997): 1–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/20173630.

Smith, Michael Peter, and L. Owen Kirkpatrick, eds. Reinventing Detroit: The Politics of Possibility. Comparative Urban and Community Research 11. New York, NY: Routledge, 2017.

Smith, Suzanne E . Dancing in the Street: Motown and the Cultural Politics of Detroit. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Sperb, Jason. “The End of Detropia: Fordist Nostalgia and the Ambivalence of Poetic Ruins in Visions of Detroit.” The Journal of American Culture; Malden 39, no. 2 (June 2016): 212–27.

Steinmetz, George. “Detroit: A Tale of Two Crises.” Society and Space 27 (2009): 761–70.

Sugrue, Thomas J. The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005.

Sumner, Gregory D. Detroit in World War II. The History Press, 2015.

Sutcliffe, John B. “Big Business and Local Government: Matty Moroun, the Ambassador Bridge and the City of Windsor.” Canadian Journal of Urban Research 23, no. 1 (Summer 2014): 55–73.

Thomas, June Manning. “Josephine Gomon Plans for Detroit’s Rehabilitation.” Journal of Planning History 17, no. 2 (May 2018): 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538513217724554.

———. Redevelopment and Race: Planning a Finer City in Postwar Detroit. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2013.

———. “Seeking a Finer Detroit: The Design and Planning Agenda of the 1960s.” In Planning the Twentieth-Century American City, edited by Mary Corbin Sies and Christopher Silver, 383–403. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Thompson, Heather Ann. “Autoworkers, Dissent, and the UAW: Detroit and Lordstown.” In Autowork, edited by Robert Asher and Ronald Edsforth, 181–208. Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1995.

———. “Rethinking the Politics of White Flight in the Postwar City: Detroit, 1945-1980.” Journal of Urban History 25, no. 2 (January 1999): 163–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/009614429902500201.

———. Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001.

Thompson, Julius E. Dudley Randall, Broadside Press, and the Black Arts Movement in Detroit, 1960–1995. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2005.

Tobocman, Steve. “Revitalizing Detroit: Is There a Role for Immigration?” Migration Policy Institute, August 2014.

Trotter, Joe W. “African Americans in the City: ‘The Industrial Era, 1900-1950.’” Journal of Urban History 21, no. 4 (May 1995): 438-57.

Vergara, Camilo Jose. Detroit Is No Dry Bones: The Eternal City of the Industrial Age. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2016.

Vinyard, JoEllen M. For Faith and Fortune: The Education of Catholic Immigrants in Detroit, 1805-1925. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1998.

Vogel, Stephen. “Detroit [Re]Turns to Nature.” In Handbook of Regenerative Landscape Design, edited by Robert L. France, 189–204. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 2008.

Walker, Samuel. “Urban Agriculture and the Sustainability Fix in Vancouver and Detroit.” Urban Geography 37, no. 2 (2016): 163–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1056606.

Wallace, Max. The American Axis: Henry Ford, Charles Lindbergh, and the Rise of the Third Reich. New York, NY: Macmillan, 2003.

Waltzer, Kenneth. “East European Jewish Detroit in the Early Twentieth Century.” Judaism: A Quarterly Journal of Jewish Life and Thought 49, no. 3 (2000): 291–291.

Ward, Stephen M. In Love and Struggle: The Revolutionary Lives of James and Grace Lee Boggs. Justice, Power, and Politics. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

White, Monica M. “D-Town Farm: African American Resistance to Food Insecurity and the Transformation of Detroit.” Environmental Practice 13, no. 4 (December 2011): 406–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1466046611000408.

Wilkinson, Sook, and Victor Jew, eds. Asian Americans in Michigan: Voices from the Midwest. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2015.

Williams, Charles. “Americanism and Anti-Communism: The UAW and Repressive Liberalism Before the Red Scare.” Labor History 53, no. 4 (November 2012): 495–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/0023656X.2012.731771.

Williams, Jeremy. Detroit: The Black Bottom Community. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

Wolcott, Victoria W. Remaking Respectability: African American Women in Interwar Detroit. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Wu, Yuning, and Jiebing Wen. “Fear of Crime Among Chinese Immigrants in Metro-Detroit.” Crime, Law and Social Change 61, no. 5 (June 2014): 495–515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-014-9513-y.

Yanik, Anthony J. Maxwell Motor and the Making of Chrysler Corporation. Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2009.

Young, Jasmin A. “Detroit’s Red: Black Radical Detroit and the Political Development of Malcolm X.” Souls 12, no. 1 (March 2010): 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999940903571296.

Zukin, Sharon. Landscapes of Power: From Detroit to Disney World. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1991.

Zunz, Olivier. The Changing Face of Inequality: Urbanization, Industrial Development, and Immigrants in Detroit, 1880-1920. University of Chicago Press, 1982.

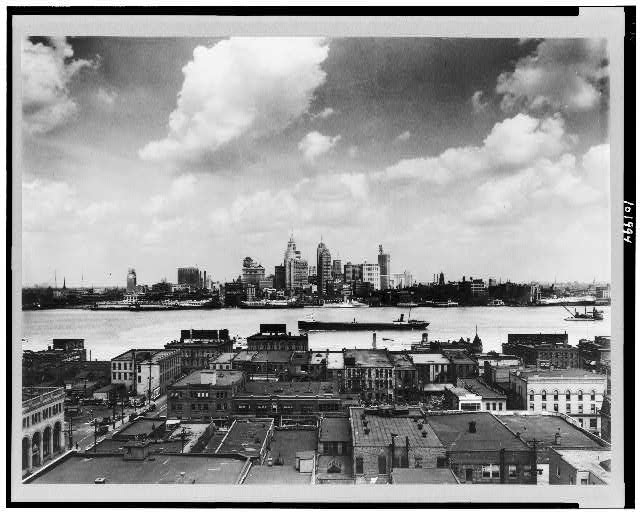

Featured image (at top): Detroit Skyline, 1929, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress