By Avigail Oren (with help from Tom Sugrue and Ryan Reft)

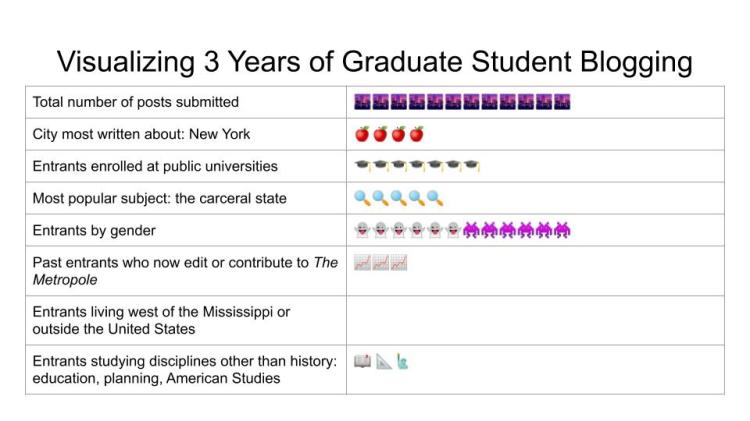

Despite having read, written for, and edited blogs for over a decade, administering the Graduate Student Blogging Contest over the past three years is what has taught me the best practices of writing history for the web. The combination of cutting-edge research, stylish graduate student writers, and astute, experienced judges has yielded several lessons that I would like to pass along here today.

A blog is a form unto itself

In the words of veteran writer and contest judge Tom Sugrue, “Blogs distill the best of academic research without the dense prose and scholarly apparatus of a book” or article. That’s the upside: a blog can dispense with methodology, historiography, and theory and focus tightly on a narrative. In fact, I’d characterize a blog post as the inverse of the scholarly form, where the narrative serves to illustrate an argument. In a blog post, the narrative leads and an argument follows.

A great example of this is “Busting Out in WWII-Era Brooklyn.” Emily Brooks lures the reader in with the story of five teenage women who escaped from jail in 1944. A compelling story, but why does it matter? Brooks tells us that “Mary, Margaret, Estelle, Carmen, and Jean’s dramatic escape created a number of public relations problems” for the city, because it “challenged the power of the state to control the behavior of young women during World War II, and forced city officials to reframe discussions around the necessity of this control.” This gives the reader a clear idea of the stakes that teenage women and the police department faced in wartime New York City. With that established, Brooks is able to depart from the narrative for two paragraphs to explain important changes that occurred in women’s social lives and employment because of the war, and likewise how the war shifted police priorities. The piece then quickly returns to the teenage women and how Estelle’s mother “lodged complaints with members of the NYPD and the mayor” for jailing them on baseless charges. Brooks concludes that the story of their escape “provides a small window into a few days in the lives of five of the young women that police, court, and political leaders deemed so threating to the health of the city and nation in wartime.” Over 3,000 readers flocked to this “small window,” fascinated by the teenagers’ daring and the NYPD’s foolishness.

Of course, there is a downside to this approach. To return again to Sugrue’s wisdom, “The drawback of blogs is that they can tend toward the superficial; they aren’t the best medium for presenting original, complex arguments.” Oftentimes this is because no single narrative can do all the work. Historians build arguments from multitudes of instances and examples. Focusing on a single narrative can force you to dispense with a lot of your more challenging anecdotes in favor of one that is simple and has a compelling character or dramatic arc.

That said, I believe that connecting with the audience is the priority. Pick a good story and stick to it. Weave your claims into the story, rather than leading with your claim. And always ask yourself – does this detail serve the story?

Respect your reader

When you are writing blog posts, keep your audience in mind. By that, I do not just mean that you cannot assume what your reader does and does not know. I mean that you need to respect your reader’s intelligence, their desire to learn, and their limited time by picking one key idea to share with them.

When you are picking that key idea, remember that even though readers might not be privy to scholarly debates, they want to know what scholars are researching. Sugrue points out that blogs usually “engage in more pointed and less scholarly debates, and reach readers who will never find their way to the Journal of Urban History.” So, think about how your research intervenes into current historiography and find a way to talk about it that centers your innovation without getting bogged down in the wider scholarship.

The winner of last year’s Graduate Student Blogging Contest, Angela Shope Stiefbold, managed this feat quite masterfully in “The Value of Farmland: Rural Gentrification and the Movement to Stop Sprawl.” Stiefbold begins by connecting to conversations that are familiar to her audience: “Rents are rapidly rising. Property values are skyrocketing. Real estate taxes are ever-increasing. Long-time owners are selling out and moving away. Newcomers express values and politics at odds with older residents. This sounds like a gentrifying urban neighborhood—but it was the situation in not-long-to-be-rural, mid-twentieth century Bucks County, Pennsylvania.” Immediately, the reader recognizes that this post is a twist on a contemporary debate—but Stiefbold then shares that it is also at the center of scholarly debates too. “The history of suburbanization has largely been written in order to understand the experience and motivations of the people who moved from city to suburb,” she writes, but those stories leave out “the perspective of the farmers who were living in the rural areas to which suburbanization came.”

Stiefbold sticks closely to this perspective as she unspools her narrative about how farmers debated whether (and how) farmland should be preserved. But at the end, she admits to her readers, “In presenting this summary, I have simplified a great deal of the contentious public debate over the fate of Bucks County’s farmland and farmers.” This candor reflects a trust in the reader—that they will understand the reason for the simplification and might still have an appetite for the greater complexity (which she briefly elaborates on). It’s what makes the post so effective: one point, clearly made, with respect for the readers’ interest.

Blogs are actually a really good format for balancing simplicity and complexity. If you think most, but not all, readers will know the background context of your narrative, you can link to another article rather than rehashing it. Same for readers who might be interested in historiographical debates about the topic—link them to it. And if your argument really is too big for one blog post then maybe it means you need to write two linked posts.

Last point: use concise prose free of scholarly jargon. It’s ok to be colloquial.

Use media to your advantage

It is expensive to print images and maps in books or print journal articles and impossible to embed links and videos. Blogs are the place where you can share archival sources or images with your readers to help illustrate your point. According to Sugrue, blogs “can (and should) use illustrations and maps in a more interactive way than print permits. And they can (and should) incorporate audio-visual materials where appropriate.”

It is expensive to print images and maps in books or print journal articles and impossible to embed links and videos. Blogs are the place where you can share archival sources or images with your readers to help illustrate your point. According to Sugrue, blogs “can (and should) use illustrations and maps in a more interactive way than print permits. And they can (and should) incorporate audio-visual materials where appropriate.”

Vyta Baselice’s “The Way Concrete Goes” uses images masterfully to demonstrate the ubiquity of the building material and the environmental devastation it wrought. She includes photographs of quarries and processing plants and the workers and equipment that were needed to bring concrete to market. Through these illustrations the reader can instantly see that this was dirty, dangerous labor. But images also show the awe-inspiring strength of this material (the Hoover Dam) and its fragility (a demolition site). Her text certainly stands on its own, but it is especially effective for its inclusion of archival images and photographs.

There are exceptions to every rule

Sometimes an argument is good enough to lead off with. What make it good enough? I’d say that it’s when an argument intervenes into an ongoing, mainstream debate or narrative. Why? Your audience won’t really require a narrative to familiarize them with the stakes of your claim.

Sometimes historiography is the point and the argument. If your blog post is telling readers that we used to understand x history this way, but now we understand it another way – well, you can’t leave out the historiography. Just make sure it’s relatable to your reader.

Sometimes your argument is a two-parter. That’s ok! Just be concise. Respect your readers’ time. Sometimes one narrative is not enough. The onus is then on you to help the reader connect the dots between them.

Sometimes there are no good images or videos or maps or links. That’s ok! Make sure everything about your text is sharp: narrative, argument, and the stylishness of your prose.

Editors are your friends

Always remember this: do your best, and an editor will help you fill in any of your gaps. In two and a half years of editing The Metropole, I can count on one hand the posts that never went back to an author for a round of revisions or approval of edits. Perfection is the enemy of done.

Featured Image (at top): Reading lesson 1500, writing lesson 1500, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

2 thoughts on “Lessons Learned from Three Years of the Blogging Contest”