By Mariana Valverde and Alexandra Flynn

In May of 2017, Waterfront Toronto (WT), a tri-government agency, issued a Request for Proposals (RFP) seeking an “innovation and funding partner” for a “smart city” plan on a small site on the waterfront.

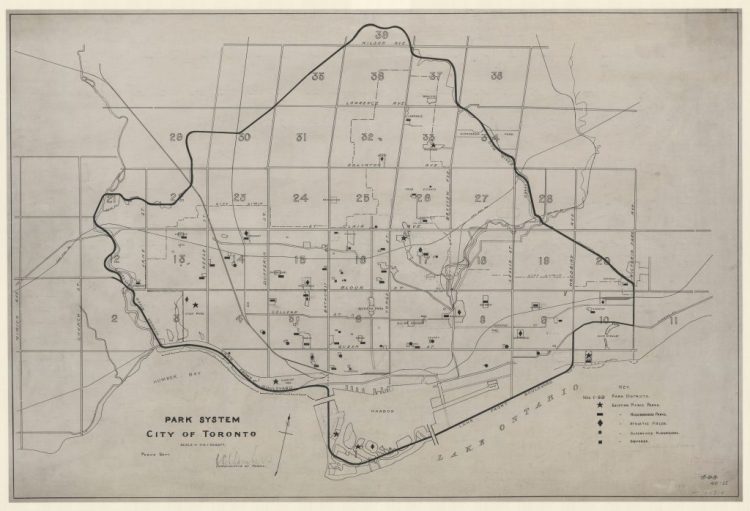

This RFP marked a major departure for a public agency that had long been assembling and cleaning up contaminated brownfield sites (mostly publicly owned) along the edge of Lake Ontario to facilitate development. Despite the prevalence of massive high-end condos along the shoreline, for most of its 20-year life WT had a good reputation for public-mindedness. Its early strong links with local environmentalists gave it credibility (even though no environmentalists have been on the board for years now). WT also brokered a small amount of new public housing and a few buildings of public benefit, and built a few small but aesthetic public spaces. The early political capital acquired amongst the ‘creative classes’ and waterfront condo dwellers helped WT gain early support for the bizarre idea of asking a private foreign company to not only build but design a world-leading “smart city”.

Sidewalk Labs (SL), an offshoot of Alphabet and so sister company of Google, won, in record time, the RFP, in the summer of 2017. From its birth in 2016, the CEO of Sidewalk Labs has been Dan Doctoroff, a financier who served as deputy mayor of New York City when his former boss Michael Bloomberg was mayor. SL has great ambitions to use urban spaces to advance digital innovations, but so far it has not developed any actual urban spaces. As a corporation, however, it has had an active life, with many subsidiaries having been spun off, some of which are registered as lobbyists in Canada – subsidiaries whose inner workings are completely obscure but whose names suggest they work on such things as health-related services and traffic management, fields that in Canada are actually wholly within the public domain.

Just what role SL proposes for itself is unclear. The most recent agreement with Waterfront Toronto, signed in July 2018, states that SL is not acquiring and will not acquire any interest in land: but the company’s recently issued ‘Master Innovation and Development Plan’ (MIDP), released in June 2019, boldly proposes to purchase some land and draw up a plan for it, acting as “lead developer” in one area –in addition to “helping” to obtain financing for transit, a peculiar role for a tech company to assume.

If the scope of the proposal is both ambitious and vague, the normally simple question of geographic reach is also very fuzzy. Waterfront Toronto had prior permission from the constituent three governments to assemble a 12-acre plot at the bottom of Parliament street, a space known as ‘Quayside’. The RFP mentioned at the outset accordingly highlighted this space –while also making noises about the need for scaling up into a part or all of the nearby 800-acre Port Lands (the largest mainly undeveloped prime urban space in North America).

Given the generally good reputation that Waterfront Toronto had enjoyed (as mentioned above), it took locals quite a while to start raising critical questions about both the choice of a Google-related company as a kind of urban developer and also about the procurement process. According to federal government emails obtained by a journalist, and also a critical report by the Ontario Auditor General, the federal government was heavily involved behind the scenes, firmly steering Google and its offshoots in the direction of Waterfront Toronto. Rather unwisely, former Google CEO Eric Schmidt publicly gloated, in November of 2017, that he and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau had been talking “for a couple of years” about a potential ‘smart city’ project in Toronto – which would date the conversations to the October 2015 election that brought Trudeau to power.

Another indication that legal niceties were not necessarily observed was when WT Vice-president Kristina Verner stated, at a public event at the University of Toronto in January 2018, that a technically innovative project could not be carried out within the small space of Quayside and would have to be ‘scaled up’ – as if a company’s technical needs automatically trumped both private property rights and jurisdiction. Making matters worse, when asked to share the criteria for choosing the winning bid at an early well attended public consultation, Ms. Verner named “nothing in particular, just a general impression” – as if that is how government contracts are supposed to be awarded.

Many reports in the international as well as local press on the ‘Google city’ proposal have focused on the potential for massive data mining and surveillance. Those are very important issues but they are somewhat separate from the kinds of questions that urban historians and urban scholars generally would ask about the way in which a public special-purpose agency got into bed with Google companies. Importantly, WT has not informed the public about its own limitations as a public corporation. As the provincial auditor general noted, if WT had been created as what Canadian law calls a Crown corporation then it could have signed unusual contracts more autonomously. But when it was created in 2001 as a tri-government agency (a rare beast in the world of public agencies), it was specifically prevented, by statute, from spending even already allocated funds without the explicit permission of all three governments.

WT was and remains straitjacketed in its development deals; unlike other public agencies it can neither generate subsidiaries (the usual mechanism used to create public-private partnerships) nor can it borrow money on its own credit.

Perhaps Dan Doctoroff, coming from New York, believed WT to be the local equivalent to the New York Port Authority. If so, he has been paying the price, now that opposition to SL has coalesced, for his ignorance of the huge legal and financial differences between the two entities. They both have to do with waterfronts but the similarity ends there. The Port Authority was created by two states and is not accountable to municipalities – New York City included. The Port Authority issues bonds and has its own credit rating: it owns important revenue streams like bridge and tunnel tolls, and, importantly, it is exempt from city zoning. Many other special-purpose bodies and development authorities, in the US and around the world, have similar powers; being exempt from municipal zoning is unusual, but the ability to create subsidiaries and issue bonds or debentures is very common in the world of urban development corporations.

By contrast, on Toronto’s waterfront the legal and governance situation is far different – the city holds much more authority than is the case in New York (or in London, we might add). In addition to its zoning power and control of local infrastructure, the city also owns almost all of the land in the Port Lands.

Neither WT nor SL mention the that the Port Lands is a difficult space to develop due to its highly toxic soil and rising watertable, a fact very important to the development of the ‘smart city.’ Currently, there is a three-government $1.5 billion plan to remediate some of the Port Lands soil while constructing a huge flood protection barrier, and the plan for that project (which does not mention SL) is quite transparent about the soil remediation issues and associated cost projections. However, in relation to the ‘smart city’ plan, obfuscation on soil remediation has been the strategy used by both SL and WT. One of us (Valverde) spent months trying to get WT staff to answer the simple question of whether the 12-acre waterfront space known as Quayside had already been remediated. We assumed it had been prior to the RFP; spending public money to remediate land then sold by WT to developers is the agency’s normal modus operandi. Eventually WT stated that the land at Quayside is not remediated, and that the costs of the remediation would be born by the ‘private partner’. Asked whether that meant SL was assuming those risks and costs in their plan, the answer was that maybe the private partner would be SL but maybe it would be somebody else.

The environmental story, which has very serious financial implications, has not been mentioned in any of the SL documents and plans. In his many appearances on Canadian media outlets, Dan Doctoroff always describes the Port Lands as an undeveloped wasteland, with no acknowledgement of the fact that the condition of the soil is precisely the reason why there aren’t already forests of condos and office buildings there.

Indeed, instead of addressing the toxicity issue and saying something about how soil remediation costs will be handled, the SL June 2019 plan (whose 1500 pages are remarkably lacking in concrete detail) states that SL should be able to buy waterfront land at less than market price –because of the obligation (by WT general policy) to provide at least some affordable housing.

Special-purpose public agencies run by appointed boards usually stay out of public view, and urban-beat journalists spend most of their time following the doings of city council and city staff, by necessity because arms-length agencies do not usually have meetings that are open to the public and often do not post minutes online. But in this case citizens might eventually get to peer into the innards of Waterfront Toronto, since in May of 2019 the Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) commenced a lawsuit against WT, claiming that the entity never had the power to issue the original RFP (The CCLA’s legal arguments are posted on its website). The suit –which has yet to be heard in court– is fascinating for urban studies, and has relevance in the US as well as Canada, since public agencies in both countries share similarities. So a word about the larger ‘public agency’ category that includes WT is in order here, before we go back to Sidewalk Labs’ plan.

There is no standard template for these entities (variously called ‘boards’, ‘authorities’, ‘agencies’, or ‘commissions’, with those four names lacking distinct legal meanings). Many are strictly local, including the numerous wholly owned subsidiaries of municipal corporations. Others are provincial/state-level but are not part of a government department. Their legal and financial powers are set out in founding documents (usually acts of the legislature), on a one-off basis. Many private lawsuits against such corporations have taken place; but court decisions on such lawsuits shed no light at all on the fundamental governance and accountability issues currently highlighted in the CCLA lawsuit.

Public agencies that are not within government proper are usually created by just one level of government. Several governments at the same level often cooperate, as when a water district is formed to provide drinking water to several municipalities. But WT, it cannot be sufficiently stressed, is rarer than a unicorn tech company, because it was formed by and is accountable to all three levels of government. In the years since its birth in 2001, it has assembled and remediated brownfield land and obtained pre-approvals from the city to help develop much of the waterfront. But at every step, it needs to go to all three levels of government for separate permission. The three governments rarely trust one another: their historic mutual mistrust is the ultimate reason why WT is unlikely to ever receive more autonomy.

Why was WT created in this way, being charged with a monumental urban development and environmental task but not allowed even to issue bonds? For a simple, quite accidental reason: WT was created as a rare three-government agency because it was the direct outcome of Toronto’s failed bid for the 2008 Olympics, and the IOC wouldn’t even look at a bid that excluded a relevant level of government. (We do not know whether Doctoroff, who played a role in New York City’s own failed Olympic bid, was aware of this history; but in any case, the failed bid did not leave behind a tri-government agency in the New York area).

WT began to think about the projected drastic falls in future government funding in 2013-14, and tried to devise a strategy for extending its own life beyond the 25-year limit set out in the founding statute. (Of course at the time it could not have been predicted that the $1.5 billion Port Lands flood protection plan would be approved a few years later). This strategy was laid out in a document titled “Waterfront 2.0”. The bureaucracy’s survival plan focused on two very tired public sector proposals for generating new revenues: philanthropic funding of specific projects, on the one hand, and on the other hand, vaguely articulated partnerships with the private sector, especially in regard to ‘innovation’ – which here as elsewhere is reduced to innovation in the digital/technical sphere. The Waterfront 2.0 plan suggests that a certain existential anxiety if not outright panic underlay the public corporation’s otherwise unexplainable decision to fall into the greedy arms of a Google company for their next project. Public entities everywhere that face financial difficulties might want to think about the moral of this story.

Now let’s highlight just a few nuggets from the June 2019 MIDP, the SL plan, before concluding with an overview of the growing opposition to the proposal. One nugget of interest to urbanists is a hard-to-find, small-type list of the 100 or so changes to laws and regulations that would need to happen for the project, as described, to go ahead – changes not just to the rules banning automated vehicles from ordinary public streets (that, one would expect) but even to the Ontario Building Code and the federal Fisheries Act. How a foreign private company could manage to get three levels of government to collaborate on wholesale legislative change is not explained; but anyone familiar with Canadian inter-governmental affairs would say that the miracle of the loaves and fishes would be nothing in comparison to what SL expects/demands.

Another nugget worthy of international notice (since Google could well come calling on some other mayor soon) is the SL demand, already publicly dismissed as ridiculous by WT board chair Stephen Diamond, that governments get over their perpetual transit funding squabbles and immediately provide a light rail transit line direct to the proposed location of a new Google Canada headquarters. Needless to say this brazen demand did not go over well in the local press.

The WT-SL relationship may go down in history as the public-private partnership that destroyed the very notion of public-private partnerships. Why? Because the MIDP, while paying lip service to the statute that says that all three governments need to approve anything WT proposes, completely ignores many of the authorities that hold powers and jurisdictions in the area, and even calls for the complete transformation or even abolition of its direct ‘partner’, Waterfront Toronto, in Volume III.

Sidewalk Labs’ tome contemplates the creation of a future “public authority” with a lot more autonomy than WT has or is likely to acquire, without telling readers where this proposal came from and who supports it. WT has often requested greater powers, but recent communications, on their website and in public appearances by senior staff, suggest the last thing they want to do is tie their institutional fortunes to SL’s heavy-handed lobbying.

And as if contemplating the death or total transformation of their public ‘partner’ were not enough, SL calls for the creation of five new specialized semi-public entities. One would be a shadowy authority created to govern what Google calls ‘urban data’ (a Google-made category on which there’s been much critical commentary by tech and other specialists). Another ‘innovation’ would be an entity with the power to administer the spaces that Sidewalk ambiguously calls ‘open spaces’ (not quite the same as legally public spaces). Other proposals include a transit authority for the district, whose relationship to existing provincial and municipal transit authorities is not discussed.

The proposals for new, largely undefined semi-private semi-public authorities use the characteristic SL prose, whereby random technical and physical details about gadgets and building materials combine to give a certain ‘reality effect’ (an effect heightened by the constant recycling of pretty landscape architect’s drawings of places that do not exist). But the reality effect is more like what one sees in realistic science fiction rather than the prose one expects in a serious document that governments and concerned citizens can examine to decide whether to grant approvals.

The plans concerning data gathering set out in the MIDP have received a great deal of critical attention. Brock University professor Blayne Haggart, an expert on intellectual property, has been providing a highly amusing but also very informative live blogging of his reading of the MIDP. The Ryerson University Centre for Free Expression blog has also posted numerous entries that hone in on aspects of the SL proposal. On her part, local tech sector leader Bianca Wylie has been constantly commenting on the issues – not just data, privacy, and surveillance but also governance and land-deal issues. (Check out #biancawylie, you get more than tweets). And the first real scholarly article on ‘the deal’, “Urbanism Under Google,” by US legal scholars Ellen Goodman and Julia Powles, has recently been published online — a deeply researched piece that comes to very pessimistic conclusions about the state of local democracy in Toronto. And on the ground as well as online, and with an agenda far broader than the data/surveillance issues, some of the opposition to the ‘deal’ has coalesced in the loose group ‘Block Sidewalk’ (see #blocksidewalk; there is a website, not just a twitter account).

So where are we at now? As of September 2019, the ‘plan’ is being considered by Waterfront Toronto itself. WT staff rushed around town all through July to collect responses from local citizens at various sites, despite many criticisms that a huge and hard to read document needed more than a couple of midsummer weeks to be digested –only to decide in mid August that it would give itself more time, until March, to vote on the project.

If asked to take off our social science hats and try to predict the future, what would we say?

It is possible that if the SL proposal is not accepted as is by WT – as seems increasingly likely— SL and its shadowy subsidiaries may break up the proposal into parts and go to different entities, especially the city, for approval of either some part of the plan or some new smaller-scale proposal, or a single-issue plan for some other area. The summer-long lobbying of the mayor’s office by SL lobbyists, at a time when officially only WT is looking at the proposal, not the city, suggests that SL is not really taking a holiday and waiting for WT to approve or not approve the plan. It is also possible that if rebuffed by WT, Doctoroff would take his plan to some other place, perhaps a more desperate and less prosperous city in the US Rust Belt. But short of hacking into Doctoroff’s phone, it is impossible for Torontonians to anticipate what SL will do – especially since the Doug Ford government of Ontario, always ready to throw conservative-populist bombs into municipal as well as provincial institutions, has decried Doctoroff’s Port Lands territorial ambitions, but has otherwise not revealed whether it is against any and all SL proposals.

Silicon Valley has given us fast and powerful software programs, phones and computers. That’s a lot. But the ‘smart city’ plan under consideration in Toronto features Silicon Valley in a new and awkward role: as the designer and creator of new public authorities. We think that even diehard techies will balk at this. Our expertise as urban law and governance experts gives us no ability to invent algorithms: so too, the whiz kids employed by Google who are giving us the Internet of Things should perhaps be told to stick to their (digital) knitting.

Mariana Valverde is a socio-legal scholar, at the University of Toronto, whose main focus for the past 15 years has been urban governance and law, historically and in the present. She has been writing popular as well as scholarly articles on public-private local infrastructure partnerships for several years.

Alexandra Flynn is a specialist in urban law and governance, now professor at the Allard School of law at the University of British Columbia. Her doctoral project, “The Landscape of Local in Toronto’s Governance Model,” looked at the overlapping geographies and governance of city space, including the formal and informal bodies that represent residents. She has past experience as a lawyer and as in a senior policy role at the City of Toronto.

Wow! Deja vu all over again. This reminds me of the way things went in the 60’s and 70’s when the original plan to revitalize the waterfront failed as a whole, but I got to watch and work on much of it as it was passed and built in the 80’s and 90’s, one piece at a time.

LikeLike