By Susan A.C. Rosenfeld

During the second half of the nineteenth century, Lagos became an increasingly diverse, urban node on the Atlantic circuit, where slavery and freedom defined individual identities and shaped the city itself. A series of political and economic transformations contributed to the social dynamics of Lagos. The nineteenth-century transition from the trans-Atlantic slave trade to the “legitimate” commerce in palm products created new economic opportunities for non-elite Africans; in particular, many Yoruba-speaking people from the hinterland brought goods and services to the town as part of the supply chain for the new Atlantic demand.[1]

The British bombardment of the port in 1851—followed by the town’s annexation in August 1861—prompted further changes. Runaway slaves from the interior flocked to the burgeoning colony, seeking freedom and protection under the new administration. Liberated Africans—those whose slave ships had been intercepted by the British Royal Navy’s anti-slavery squadron and rerouted to Sierra Leone—also migrated to the town. There, they formed a community of Christian, African elites called the Saros. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Lagos also became the primary destination for African emigrants from Bahia who, after years of enslavement in Brazil, bought their freedom and boarded ships bound for the African coast.

Thousands of formerly enslaved Africans and their descendants repatriated to West Africa from Salvador da Bahia, Brazil over the course of the century.[2] Multiple factors contributed to returnees’ increasing interest in Lagos as a destination for resettlement after 1850. First, like other self-liberated Africans in the region, these Amaros—as Afro-Brazilian repatriates were called in Lagos—sought British protection from re-enslavement.[3] Benjamin Campbell, the consul of Lagos from 1853 to 1859, encouraged these freed Africans to emigrate from Brazil; he promised to protect them in exchange for their cooperation with the colonial administration.[4] These returnees’ decisions to settle in this particular urban port may have also been guided by their interest in trans-Atlantic commerce; the economic inflation and periodic blockades in other West African coastal cities—which resulted from the British Navy centering its activity around Ouidah and other, more western portsin an attempt to suppress the Dahomean slave trade—were not issues in Lagos.[5] Finally, many of these emigrants came from Yoruba-speaking towns in the interior. By settling in the colony, these individuals returned to their region of origin.

At the same time, while many Amaros perceived Lagos as a space of freedom in contrast to Brazil, slavery continued to exist in the colony. While the British insisted on abolishing the foreign slave trade in Lagos after their bombardment of the port in 1851, they delayed abolition in the colony itself. In her examination of slavery in nineteenth-century colonial Lagos, Kristin Mann purports that it was not until after 1866 that British officials in London argued for the prohibition of slavery in the town. However, she explains, “In the second half of the nineteenth century, the colonial state largely left it to the slaves themselves to redefine their relationships with owners. Struggle over the contested and shifting relationship between owners and slaves … dominated the history of the town in the closing decades of the nineteenth century.”[6]

In this way, an examination of the Afro-Brazilian community of Lagos illuminates the ways that the burgeoning colony was comprised of a series of contradictory, complex dynamics involving slavery and freedom, old and new, and local and Atlantic networks. For African returnees from Brazil, the memory of enslavement continued to impact their lives in Lagos, at the same time that it also defined policies and relationships in the colony during the period. In addition, for non-elite, repatriated Africans, Lagos was a space in which they reengaged with local kinship and commercial connections, while simultaneously asserting themselves as “Atlantic citizens.”[7] Indeed, after these Afro-Brazilian repatriates settled in the colony, their social and commercial networks included new relations, emigrants who they had known in Bahia, and Yoruba family members with whom they reunited. Within these relationships, they constantly (re)negotiated spaces of freedom, both in the colony and in the larger Atlantic world.

Nineteenth-century courtroom testimonies from these emigrants, contained in documents housed at the Lagos State High Court, reveal these dynamics and the ways that they impacted the lives of returnees in the colony. Ewusu, a freed Yoruba emigrant from Bahia, serves as one such example. The late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century Yoruba wars dispersed Ewusu and her family from their town in the interior; as a young girl, she was captured and sold into slavery in Bahia. In 1843, she emigrated to Lagos with her husband and a Brazilian-born child named Maria Mariquinha; ten years later, in 1853, her sister came to the port city from Sierra Leone, where she had been taken by the British after her initial capture. In an 1892 testimony, Ewusu’s nephew remembered the scene when the two sisters met for the first time in Lagos, after being apart for a quarter of a century. He told the court, “They embraced and wept together. They related the stories of the troubles they had passed through in captivity.”[8] Upon Ewusu’s death, however, her Saro relatives went to trial with Maria Mariquinha, the young girl who had emigrated with her. In a fight over who would inherit her estate, the question became whether Maria Mariquinha was a kin relation or Ewusu’s former slave. In the end, the court ruled that Maria Mariquinha did not have rights to Ewusu’s property, illustrating the ways in which slavery continued to be an important element of defining identity and kinship in Lagos colony. These mixed families of formerly enslaved Amaros, Saros, and Brazilian-born relations, like that of Ewusu, illuminates the complicated identities and kinship dynamics in the city during the second half of the nineteenth century. Nonetheless, while the condition and memory of slavery still shaped these returnees’ lives in Lagos on both individual and institutional levels at times, the colony also became a refuge for freedom for many formerly enslaved emigrants.

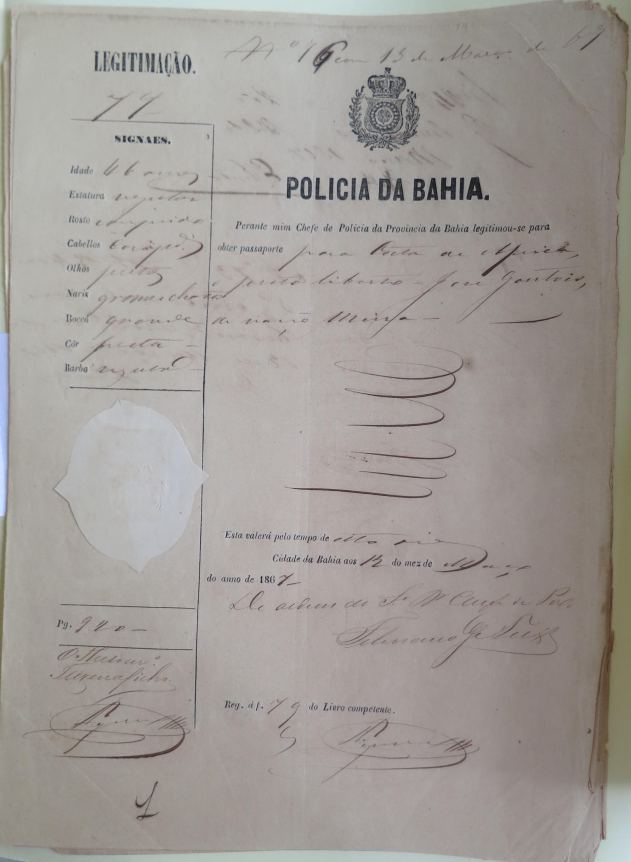

In addition to being a city comprised of complex relational networks, Lagos also served as a node of Atlantic engagement that facilitated the free movement of formerly enslaved returnees between West Africa and Brazil. While these emigrants often rekindled their Yoruba social and commercial relationships in the region, the Amaros maintained the networks that they had forged across the Atlantic, as well. Passport registers from the port of Salvador show that many emigrants made multiple trips to Bahia after repatriating to Lagos, in order to visit family or to participate in trans-Atlantic trade. The colonial policy of issuing British passports to Brazilian returnees—despite the fact that they were not considered British citizens—allowed these Amaros to travel without the risk of re-enslavement. Lisa Earl Castillo’s work on mapping the nineteenth-century Brazilian returnee movement provides insight into the origins of this practice, which Consul Campbell implemented in 1858. Castillo explains, “He [Campbell] initially envisioned this as a way of assisting those who wished to resettle in homelands in the interior rather than remain in Lagos.”[9] Campbell extended this practice to those returnees who wished to travel back and forth between Lagos and Brazil or Cuba. As Castillo notes, soon these Brazilian emigrants used their British passports “not only for international voyages but also for domestic travel within Brazil, much to the local authorities’ displeasure.”[10] Such was the case for José Godinho Bastos, a liberated African who left for Lagos in April 1876. In November of the same year, Bastos returned to Salvador on a ship that embarked from the colony; he arrived in Brazil with a British passport. In March 1877, he again set sail for Lagos; police records from Bahia note that he was still in possession of his British documents.[11] Another liberated African, Augusto João Barcellos, traveled from Rio Grande do Sul to Salvador, where he obtained a passport to sail to Lagos in 1868. He settled in the colony, where he became a farmer and a merchant. However, his trans-Atlantic business dealings brought him back to Salvador by 1889, at which point he had a British passport. He again sailed for his home in Lagos in March of that year, and the Brazilian police recorded his status as a British subject.[12]

Using their British passports, these Afro-Brazilian emigrants exercised their freedom by expanding their mobility. The colonial policies, the changing dynamics, and the diverse population of Lagos allowed these returnees to maintain and create new trans-Atlantic connections, while simultaneously rekindling the social, ethnic and commercial ties they had lost when they were sold into slavery. In this way, the city of Lagos became an important freedom hub for Africans and their descendants throughout the Atlantic during the second half of the nineteenth century. While the early-twentieth century brought additional changes and increasingly restrictive colonial policies toward Africans, the Afro-Brazilian emigrants who settled in the city during the decades before used this urban space to contest the legacies of slavery and to reimagine themselves as free members of both their local community in Lagos and their commercial and social networks that spanned the Atlantic.

Susan A.C. Rosenfeld (@sarosenfeld) is a Ph.D. Candidate in African History at the University of California, Los Angeles. Based on multi-sited research, her dissertation—“Apparitions of the Atlantic: Afro-Brazilian Freedom, Mobility, and Self-Identification in Lagos and the Atlantic World, 1851–1900,” focuses on non-elite, formerly enslaved Africans and their descendants who emigrated from Brazil to Lagos during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Susan A.C. Rosenfeld (@sarosenfeld) is a Ph.D. Candidate in African History at the University of California, Los Angeles. Based on multi-sited research, her dissertation—“Apparitions of the Atlantic: Afro-Brazilian Freedom, Mobility, and Self-Identification in Lagos and the Atlantic World, 1851–1900,” focuses on non-elite, formerly enslaved Africans and their descendants who emigrated from Brazil to Lagos during the second half of the nineteenth century.

Featured image (at top): The Bamgboshe Martins House, home of a Candomblé Egúngún from Brazil, photograph by Aderemi Adegbite courtesy of Orishaimage.com.

[1] Robin Law, ed., From Slave Trade to ‘Legitimate’ Commerce: The commercial transition in nineteenth-century West Africa (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

[2] There is an ongoing scholarly debate over the number of nineteenth-century repatriates. See Pierre Verger, Flux et reflux de la traite des nègres entre le Golfe de Bénin et Bahia de Todos os Santos du XVIIe au XIXe siècle (Paris: Mouton, 1968), 633; Jerry M. Turner, Les Brésiliens: The Impact of Former Slaves upon Dahomey (Ph.D. dissertation, Boston University, 1975), 78; Manuela Carneiro da Cunha, Negros, estrangeiros: os escravos libertos e sua volta à África (São Paulo: Editora Brasiliense, 1978), 210–16; Clément da Cruz, “Les Apports culturels des Noirs de la Diaspora à l’Afrique” (Contonou: UNESCO, 1983), 5.

[3] Carneiro da Cunha, Negros, estrangeiros, 137.

[4] Lisa A. Lindsay, “‘To Return to the Bosom of Their Fatherland’: Brazilian Immigrants in Nineteenth-Century Lagos,” Slavery & Abolition 15, no. 1 (1994): 26–27.

[5] Lisa Earl Castillo, “Mapping the Nineteenth-Century Brazilian Returnee Movement: Demographics, Life Stories, and the Question of Slavery,” Atlantic Studies 13, no. 1 (2016): 35.

[6] Kristin Mann, “Finding Slave Voices in British Colonial High Court Records: Lagos, 1879,” Conference on “Finding the African Voice: Narratives of Slavery and Enslavement,” Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Study and Conference Center, Bellagio, Italy, 24–28 September, 2007. Mann also discusses this dynamic in her book, Slavery and the Birth of an African City: Lagos, 1760–1900 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2007).

[7] This phrase is adapted to the Afro-Brazilian context from Leslie Eckel’s work on nineteenth-century writers in the United States; see Atlantic Citizens: Nineteenth-Century American Writers at Work in the World (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013).

[8] Lagos State High Court (hereafter LSHC), Judge’s Notebook, Civil Cases, 386–88, Maria Mariquinha v. David Williams, 9 February 1892.

[9] Castillo, “Mapping the Nineteenth-Century Brazilian Returnee Movement,” 36.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Arquivo Público do Estado da Bahia (hereafter APEB), Lista de Entrada e Saída de Passageiros (1876), maço 5953; APEB, Saídas dos Passageiros, Republicano No. 52; APEB, Registros de passaportes (1875–77), maço 5905.

[12] APEB, Registros de passaportes (1864–68), maço 5901; APEB, Registro de passaportes (1885–89), maço 5910; LSHC, Judge’s Notebook, Civil Cases, 48–53, Augusto João Barcellos v. Roqui João Gonsalo, 14 April 1891.

One thought on “Reimagining Slavery and Freedom: Afro-Brazilians in Lagos during the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century”