By Daniel Richter

Buenos Aires and Montevideo, the capitals of Argentina and Uruguay, are located approximately 120 miles away from each other across the Río de la Plata. Over the decade from 2003 to 2013, I traveled by boat between Argentina and Uruguay approximately 20 times while living in the two cities for an aggregate of six of those years. A fair number of these trips were primarily to renew 90-day tourist visas in Argentina, where I lived from 2003 to 2008. I was far from alone among the many Americans and other foreigners residing in Buenos Aires that would travel back and forth across the world’s so-called widest river. I had a Brazilian friend that would join me for the occasional overnight trip to Montevideo and to the closer Uruguayan port of Colonia del Sacramento for his own visa renewal reasons. I also made numerous trips to Uruguay for beach holidays in the months of December, January, and February.

Most memorably, I was once stranded on a ferry boat that failed to dock in Colonia del Sacramento due to a large thunderstorm. Our boat ran out of gas in the middle of the river, and we were towed back to the port of Buenos Aires by a tug boat. About 12 hours after leaving Buenos Aires on a planned boat trip to Colonia that would lead to a connecting bus to Montevideo and a weekend meetup with friends, I returned to Buenos Aires without having successfully stepped foot onto the sought-after Uruguayan soil.[1] The return of our stranded ferry was broadcast live on Argentine television news. My doorman in Buenos Aires told me the next day that he had seen me on television looking rather worn down by the odyssey at sea as I returned to the ferry terminal in Buenos Aires along with my fellow travelers to have our exit visa stamps cancelled.

Long before the early 2000s and my experiences with river crossings, Buenos Aires and Montevideo developed a long and shared history dating back to the late 16th century and the arrival of Spanish colonial rule in the region. During the early colonial era, Spanish settlers created a network of urban spaces in South America to administer colonial trade and settlements. Buenos Aires became the largest urban center. Across the river, Portuguese colonists founded Montevideo. By the early 18th century, Montevideo had become a Spanish colonial possession. Buenos Aires became a Spanish viceregal capital in 1776 with dominion over the whole of the Río de la Plata region. During the late 18th century, merchants in the two cities were key participants in the growth of Atlantic commerce. Buenos Aires and Montevideo both functioned as major centers for the transatlantic, trans-imperial, and regional slave trade, which expanded to the South Atlantic in the late 18th century.[2]

By the early 1800s, Montevideo’s citizens began to pursue their own political autonomy. When a Spanish colonial militia was needed to liberate Buenos Aires from a British invasion in 1806, they came from Montevideo. When Argentines and Uruguayans fought for independence from Spain during the 1810s, militia leaders in both cities forged alliances and lasting rivalries. Buenos Aires-based forces invaded Montevideo during the 1810s and then Uruguayans, led by national hero Jose Artigas, fought back to redefine the political alliances of the different regions of Argentina’s hinterland. From 1816 to 1825, Montevideo also fought for national independence against the occupation of Portuguese imperial forces from Brazil. Ultimately, Argentina won its decisive independence over a decade before Uruguay, but by the late 1820s, both Buenos Aires and Montevideo were the political centers of new nations in formation. Since then, connections between Buenos Aires and Montevideo have been shaped by ever-expanding commercial exchanges, but also by waves of migrations, political exile, boats and planes, tango and rock music, Carnival festivals, soccer rivalries, and familial ties.

In my book manuscript in progress, I examine the shared urban and cultural histories of Buenos Aires and Montevideo in the 20th century. My research focuses on the rise of Buenos Aires as a mass cultural capital in Latin America during the period from 1910 to 1960 and the under-explored role of cultural connections with Montevideo in shaping Buenos Aires’s emergence as a Broadway and Hollywood of Latin American mass culture. (I also have published an essay on the close ties between Uruguay’s small film industry and Argentina’s far more sizable cinematic industry from the early 20th century to the present).[3] My work builds on an interdisciplinary body of scholarship by Argentines, Uruguayans, Brazilians, Americans, Spaniards, and others who have paid attention to the varied aspects of connections between the two cities.[4] This essay is an exploration of the shared political histories of Buenos Aires and Montevideo that underpin my work and the second part is a brief introduction to the long history of cultural exchanges between the two cities. It is also an opportunity to argue that the long-standing connections between Buenos Aires and Montevideo as urban spaces for political exiles also speaks to the global historical importance of cities in shaping the transnational dynamics of oppositional political movements. As historian Michael Goebel has documented for Paris, an anti-imperial metropolis during the interwar period of the 20th century, it is crucial to understand how modern political movements have been shaped by the environs of interconnected cities.[5] In Buenos Aires and Montevideo, I would argue that the shared significance for urban history comes from how the two cities contributed to a shared intellectual world of universities, print culture, and the cultural effervescence of mass culture.

Political currents have repeatedly shaped Buenos Aires’s relationship with Montevideo (and vice versa) since the independence of both countries. In the 1830s to 1840s, Buenos Aires and Montevideo developed a new form of connection as Montevideo functioned as a primary site of political exile for opponents of the Argentine government led by Federalist caudillo Juan Manuel de Rosas. Political exile of prominent Argentines in Montevideo and Uruguayans in Buenos Aires is a pattern that has repeated itself again and again. During most of the period from 1829 to 1852, Juan Manuel de Rosas was the Governor of Buenos Aires Province (including the city) and his opponents were members of the Unitarian political party. The most famous Federalist slogan was the succinct “Death to Unitarians.” The Unitarian Juan Bautista Alberdi, Argentina’s most prominent constitutional thinker and arguably the country’s James Madison, was exiled in Montevideo in the 1830s and early 1840s. Alberdi and other intellectuals wrote for Montevideo publications such as El Iniciador and imagined a post-Rosas Argentina from Uruguay. Alberdi was joined in Montevideo by Florencio Varela, Esteban Escheverria, Hilario Ascasubi. As literary scholar William Acree has written, Ascasubi was the most potent pen in angering Rosas and his allies.[6] (Another prominent anti-Rosas intellectual and eventual Argentine president, Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, was exiled in Santiago del Chile, in large part because it was closer to his native San Juan in northwestern Argentina.)

In Montevideo during the 1840s, Alberdi fled during a siege of the city led by the forces of the Uruguayan general Manuel Oribe and backed by Rosas from Buenos Aires. In 1848, Varela was assassinated in Montevideo on orders from Oribe and Rosas, an act of political violence that would echo throughout the late 20th century with Argentines and Uruguayan civilians targeted while in exile from their respective homeland. After the fall of Juan Manuel de Rosas in 1852, Montevideo was not as synonymous with exile from Buenos Aires for the duration of the 19th century.

During the 20th century, the cities would continue to switch roles back and forth as sites of exile. The Uruguayan capital would become a privileged space of exile for a few anti-Peronist politicians during the first government of Juan Perón from 1945 to 1955. Argentine intellectuals would also seek employ at the Universidad de la República in Montevideo during this period, including the University of Buenos Aires professor and historian José Luis Romero.[7] In the 1960s, more Argentine intellectuals would go to Montevideo when the University of Buenos Aires’s administration was taken over by another in a long array of military governments. In the early 1970s, Uruguayan politicians, intellectuals, and leftist activists would flee to Buenos Aires after the Uruguayan military began to violently repress Uruguayans considered opponents of the new junta. In March 1976, Argentina suffered a violent military coup and the new regime murderously targeted both Argentine and Uruguayan political opponents in Buenos Aires. A number of prominent Uruguayan politicians had chosen exile in Buenos Aires since 1973. Among them were Zelmer Michelini and Héctor Gutierrez Ruiz. Michelini was a Uruguayan senator and political leader of the Frente Amplio political movements in Uruguay. In May 1976, Michelini and Gutierrez Ruiz were kidnapped and killed on the same day in Buenos Aires. The murders were the work of military officers involved in Operation Condor, the transnational network of political assassinations involving military and intelligence officers in Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Brazil.[8] Since the return of democracy, human rights organizations in both Buenos Aires and Montevideo have worked together in pursuit of justice and accountability for this period of state terrorism.

Eduardo Galeano, the Uruguayan writer and committed leftist, wrote in the heartrending “Chronicle of the City of Buenos Aires” in his The Book of Embraces about his experience of returning to Buenos Aires in 1984 after fleeing Montevideo in 1973 and then having to escape in 1976 from Buenos Aires to Spain.[9]

In the middle of 1984, I traveled to the River Plate. It was eleven years since I’d seen Montevideo; eight years since I’d seen Buenos Aires. I had walked out of Montevideo because I don’t like being a prisoner, and out of Buenos Aires because I don’t like being dead. By 1984, the Argentine military dictatorship had gone, leaving behind it an indelible trace of blood and filth, and the Uruguayan military dictatorship was on its way out.

The exile of Uruguayan writer Mario Benedetti coincided with Galeano’s in Buenos Aires before he too departed for another exile in Lima, Peru. Benedetti’s short story “La vecina orilla” (in translation with the title of “The Other Side”) is an evocative tale of the exile of a young Uruguayan political activist in Buenos Aires.[10] The two stories shared the experiences of both writers and the conditions of double exile that shaped the lives of many Montevideo natives who felt almost at home in Buenos Aires during a dark chapter of Latin American history.

While political exiles colored the relationship between residents of Buenos Aires and Montevideo at decisive moments in the 19th and 20th centuries, decidedly more cultural exchanges proliferated during the same period and were not shaped by formal politics. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Podesta family popularized the Creole circus in cities including Buenos Aires and Montevideo and numerous towns throughout Argentina and Uruguay. In the early 20th century, playwrights and performers from both cities increasingly traveled back and forth between Buenos Aires and Montevideo to forge a shared world of popular culture. The two cities also functioned as incubators for the world’s greatest tango singers, musicians, and composers during the 1910s and 1920s.[11] For Uruguayan dramatists like Angel Curotto, Buenos Aires’s Avenida Corrientes was the South American equivalent of Broadway and increasingly offered what Montevideo could not. However, with the rise of Peronism in Argentina during the 1940s, numerous leading Argentine performers pursued theatrical opportunities in Montevideo where there was less political tension and censorship. Curotto became a major figure in attracting Argentine directors and performers to Montevideo’s Teatro Solis in the late 1940s and early 1950s.[12] With the rise of film culture in the 1930s and 1940s, Buenos Aires simultaneously attracted more and more performers from Montevideo and Santiago del Chile to pursue their dreams on screen while working for Argentine film studios. At the same time, mass audiences filled Buenos Aires’s dozens of movie theaters, thereby popularizing Argentine films. In addition, Buenos Aires developed as urban metropolis for various exiles; many of these figures contributed to the city’s mass cultural marketplace in different forms of intellectual production. In the late 1940s, the African-American writer Richard Wright opted to film an adaptation of his novel Native Son in Buenos Aires while collaborating with the émigré French director Pierre Chenal.[13]

During the 20th century, Buenos Aires and Montevideo continued to influence each other’s imaginations. The Hotel de los Pocitos, located on the Río de la Plata beachfront in Montevideo, was a prominent vacation destination for middle and upper-class Argentineans in the early 1900s before being destroyed by a hurricane in 1923. Montevideo’s “salubrious climate” attracted international visitors and helped to transform it into a summer resort for Uruguayans, Argentines, and Brazilians during the early decades of the 20th century.[14] By the 1950s, Argentines began to vacation en masse in Uruguay’s ocean town of Punta del Este, which had more coastline than the Argentine capital and was largely on the Atlantic Ocean. In different moments, residents of Buenos Aires imagined Montevideo as a city of anti-Peronism, frequent business trips, extramarital affairs, and offshore accounts. Buenos Aires occupied the urban imagination of montevideanos as South America’s modern metropolis, and in the 1960s and 1970s as a city of revolutionary and then violently repressive politics. These urban imaginaries ebbed and flowed to shape generations of porteños and montevideanos. In the framework of transnational urban history, my work grapples with the appropriate comparisons to explore the relationship between the two capital cities. Many comparisons come to mind, but the cities lack the clear political schisms of Havana and Miami, are not equally global and political metropolises like London and Paris (and do not differ in languages), and unlike New York and Toronto the cities exist in closer proximity and function as national capitals. My framing of the comparative and transnational histories of Buenos Aires and Montevideo seeks to trace the connections between the cities as contributing to Buenos Aires’s place as a capital of Latin American mass culture and builds on the longer histories of political and cultural connections between Argentina and Uruguay.

Daniel Richter is a Lecturer in the Department of History at the University of Maryland. He received his doctorate from Maryland in Latin American history in 2016. His research focuses on the urban and cultural history of 20th century Latin America, transnational urban history, and global histories of mass culture and commodities.

Daniel Richter is a Lecturer in the Department of History at the University of Maryland. He received his doctorate from Maryland in Latin American history in 2016. His research focuses on the urban and cultural history of 20th century Latin America, transnational urban history, and global histories of mass culture and commodities.

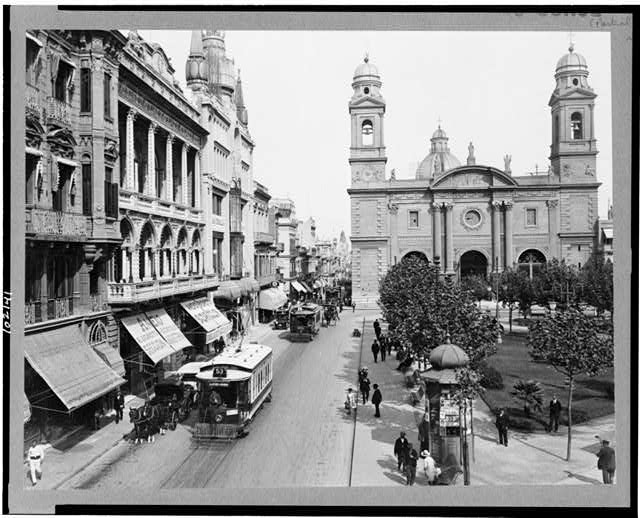

Featured image (at top): The Atheneum, Montevideo, Uruguay, between 1908 and 1919, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

[1] “Pánico y quejas en Buquebus,” La Nación, February 24, 2006, https://www.lanacion.com.ar/783606-panico-y-quejas-en-buquebus

[2] Alex Borucki, “The Slave Trade to the Río de la Plata, 1777–1812: Trans-Imperial Networks and Atlantic Warfare,” Colonial Latin American Review, Vol. 20, No. 1 (2011): 81-107.

[3] Daniel Richter, “Big Screens for a Small Industry: A History of Twentieth-Century Uruguayan Cinema,” Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. Available online: http://latinamericanhistory.oxfordre.com/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.001.0001/acrefore-9780199366439-e-341?rskey=fXixMP&result=6

[4] Roger Mirza, Teatro rioplatense: cuerpo, palabra, imagen: la escena contemporánea, una reflexión impostergable. Montevideo: Unión Latina, 2007.

[5] Michael Goebel, Anti-Imperial Metropolis: Interwar Paris and the Seeds of Third World Nationalism. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

[6] William G. Acree, Jr., Everyday Reading: Print Culture and Collective Identity in the Río de la Plata, 1780-1910. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2011, 72-74.

[7] Juan Carlos del Bello, Osvaldo Barsky, Graciela Giménez, La universidad privada argentina. Buenos Aires: Libros del Zorzal, 2007, 69.

[8] John Dinges, The Condor Years: How Pinochet And His Allies Brought Terrorism To Three Continents. New York: The New Press, 2012, 145-147.

[9] Eduardo Galeano, The Book of Embraces. Translated by Cedric Belfrage with Mark Schafer. New York: W.W. Norton, 1992, 188-189.

[10] Mario Benedetti, “The Other Side,” in Blood pact and other stories, edited by Claribel Alegría and Darwin Flakoll. Translated by Daniel Balderston. Willimantic, Connecticut: Curbstone Press, 1997.

[11] Juan Carlos Legido, La orilla oriental del tango. Historia del Tango Uruguayo. Montevideo: Ediciones de la Plaza, 1994.

[12] Daniela Bouret and Gonzalo Vicci, “Relaciones creativas y conflictivas entre el teatro y la política. La institucionalidad de las artes escénicas en Uruguay en la Comisión de Teatros Municipales,” Telondefondo. Revista de Teoría y Crítica Teatral Publicación semestral (December 2011), 123-143.

[13] Edgardo Krebs, Sangre negra: breve historia de una película perdida. Mar del Plata: Festival Internacional de Cine de Mar del Plata, 2015.

[14] Edward Albes, Montevideo, The City of Roses. Washington, DC: Organization of American States, 1922.