By Matthew J. Guariglia

During the nineteenth century, until the passage of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, it is estimated that Chinese immigrants made their way to the United States by the hundreds of thousands. In 1900, 18 years after the massive restrictions led to a major decline of the U.S. Chinese population, there were around 7,000 Chinese or Chinese-descended residents of Manhattan’s Chinatown. In San Francisco’s Chinatown, which had a population of as high as 25,000 in 1890, the 1900 population now teetered at around 14,000. The decline of Chinese population, however, did not reflect in mounting municipal concerns over the threat of crime and contagion that Chinatowns posed to the sprawling cities around them. During the turn of the century, community desires to curb crime and retain the protections of the police was often complicated by the frequent brutality inflicted by police. Despite the fact that becoming more legible to the state often means becoming more susceptible to coercive mechanisms of power, collaboration between “native” police and majority-white police departments may have seemed to some upwardly and racially-mobile immigrants like an efficient way to provide police protection to a neighborhood without as much overt physical violence, though archives accessible now are filled with evidence to the contrary.

Other scholars, particularly Nayan Shah, have done excellent work in demonstrating the coercive over-policing done by health inspectors in San Francisco’s Chinatown, but much less has been written on the ways in which municipal police departments struggled to exert control over the language and cultural barriers that seemingly shrouded Chinatown. For both San Francisco and New York City’s police departments, the confusion of white officers policing Chinese populations are well documented in police memoirs and newspaper accounts of the era. Full of vicious stereotypes and unchecked sensationalism, many in police walked Chinatown with little or no desire to understand their surroundings. “There is probably no American who does not regard the Chinese as beings dissimilar to and dissonant with himself; as a caste shut out by its fantastic personality from his sympathies and associations,” wrote former NYPD chief George Walling in 1887, before referring to the language, writing, and religion in the neighborhood as “fantastic and bewildering.”

One attempt at extending state control into Chinese neighborhoods came under the 1896 headline “A Queer System of Espionage in the Oriental Quarter of San Francisco.” Organized by the Merchant’s Law and Order League, six companies of Chinese police were organized who, once a week, reported directly to the China’s consul-general in San Francisco. Whenever they deemed that a Chinese San Franciscan had committed a crime severe enough, the Chinese police were dispatched to summon a member of the San Francisco police, and the offender was arrested. “When they first became active agents in the Chinese quarter,” read the San Francisco Examiner, “Chief of Police Crowley was informed of their object and told of the advantages that would accrue to the department through their services. They were consequently provided with a sort of card identification or credentials.” Although it’s unclear how long this arrangement, made between the Chinese community, the Chinese consul-general, and the SFPD, lasted, the police department did not swear in a full officer of Chinese or Chinese-descent until Herbert Lee took the oath in 1957.

While more and more scholarship is being produced that reveals the intellectual and physical labor behind U.S. state building and the increase of that state’s capability to exert power during the Progressive era, there is still much work that is yet to be done about how communities, like the residents of New York and San Francisco’s Chinatowns, chose to resist or embrace the privileges and injustices that came along with an increased ability to police the neighborhood.

Matthew Guariglia is the editor of The Metropole’s Disciplining the City series and a PhD Candidate in the Department of History at the University of Connecticut. His most recent work on the dangers of overzealous government surveillance appeared in the Washington Post for its “Made by History” series earlier this summer.

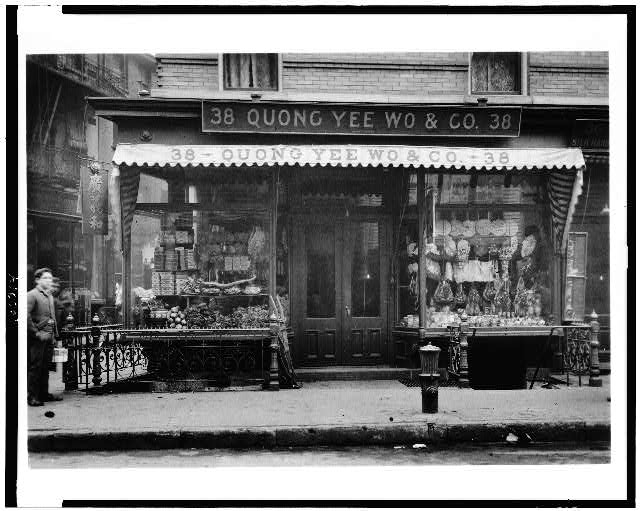

The Photograph at the top of the page, ” [San Francisco Chinatown, 1895-1900(?): busy scene on commercial street]” can be found in the Prints and Photographs Division at the Library of Congress.