[Editor’s note: To see our other selections for Best of 2025, see here]

How many times have you bought a book at a conference or at a bookstore, with the full intention of reading it posthaste, only to stumble upon it again twelve months later when you finely dig in? Unlike an album or a film, it takes more than two hours to read and fully absorb a book. All this is to say our Best Books of 2025 may really the best books we read in 2025 that were published in the last three months or three years, but that is an awkward heading. Anyway, here are the new(ish) books our senior editors read in 2025 (and other books that might relate to the newer ones in our rotation; we’re historians, what can you do?).

Ryan Reft

I’ve never been a big fan of biographies, but my job demands I read them fairly regularly, and occasionally I stumble upon one that really delivers. One of my main work responsibilities is covering 20th and 21st century domestic politics and policy, so the rise of the New Right figures prominently, and arguably no one symbolizes that shift more than Ronald Reagan. However one feels about the Reagan presidency, historians and biographers have long attempted, largely unsuccessfully, to capture his character and policy in one work.

For my money, Joan Didion saw his personage with the most clarity, “as a mystical supernatural figure, akin to Peter Seller’s Chance from Being There.” But one can only depend on her insights so much, since she hated the Reagans. She once described Nancy Reagan as a woman who “collected slights” taking “refuge in a kind of piss-elegance, a fanciness … in using words like ‘inappropriate.’”

Outside of Didion, Edmond Morris’s 1999 work Dutch (1999) might be the best book depicting Reagan as a person but it’s also a bizarre work in which Morris creates a fictional narrator who functions as a window into the president’s soul from Dixon, IL, to Washington D.C.. It’s like reading literary fiction and it definitely works on one level, but as a history it’s not the most reliable work. Enter Max Boot’s Reagan: His Life and Legend. More than any of the several biographies dedicated to the president, Boot highlights the strengths and weaknesses of the man and his movement. Boot, who many observers would argue, comes from the (now defunct?) neoconservative wing of the conservative movement, leans into aspects of Reagan’s presidency, but also offers numerous critiques and rejoinders regarding it and the New Right that rose up around him. It’s the most balanced account of the presidency and for those arguing that the current moment can be traced back to more ostensibly benign leadership decades earlier, it certainly provides a roadmap.

With the 250th anniversary of American nearly upon us, there are sure to be a slew of new works on the Declaration of Independence, the Revolution, and so forth. One of the best to come out recently is Michael Hattem’s The Memory of ’76, which walks us through how Americans have remembered the Revolution and the Declaration of Independence over their entire 250 year history. The Revolution, and especially the Declaration, was not always front of mind for Americans. During the nation’s first few decades, it was an elite-driven history focused on Washington, Jefferson, Madison and so on, but following the War of 1812, attention shifted to the Continental Army and the role of more common folks in events. Hence, historical context played a key role in the depiction of the Revolution and the Declaration. For example, the nineteenth century anti-slavery and women’s suffrage movements deployed the Declaration’s guarantee of equality and the Revolution’s support of such themes in their own fight to end slavery and ensure women’s right to vote, while the southern confederacy eschewed the Declaration, holding up the Constitution as the true arbiter of Americanness. “The Revolution became an emblem of a long-standing heritage that people could relate to, but it was also devoid of any ideological meaning,” writes Hattem. “Such a void enabled individuals to define the meaning of various revolutionary symbols for themselves in whatever ways were most convenient and useful.”

If you do pick up The Memory of ’76, consider checking out earlier books on the topic: Our Declaration: A Reading of the Declaration of Independence by Danielle Allen, and Pauline Meyer’s American Scripture: Making the Declaration of Independence. Taken together, the three provide a clear sense of the Declaration’s role in our history at the time of revolution and in the decades and centuries that followed. I’d also throw in M.J. Rymsza-Pawloska’s History Comes Alive: Public History and Popular Culture During the 1970s, which explores the bicentennial celebration in 1976, which is a useful juxtaposition to next year’s approaching semiquincentennial.

I reviewed Margot Canaday’s Queer Career: Sexuality and Work in Modern America, for the The Metropole in 2023 and recently returned to it for a research project I am working on which reminded me of how good it is and how much Canaday has reshaped the field with Queer Career and her earlier book, Straight State. Though Queer Career is technically not an “urban history,” it inarguably functions as one and with legal rights under threat, seems more important than ever.

For the same project, I also delved into new works on Silicon Valley, namely Malcom Harris’s very ambitious Palo Alto: A History of Capitalism, California, and the World and Margaret O’Mara’s The Code: Silicon Valley and the Remaking of America. While Harris covers a lot of ground, his book can also lack coherence, particularly as he attempts to weave pop culture, Marxist economic theory, and global history into a narrative about Silicon Valley. O’Mara’s The Code, however, delivers a thorough but also tailored encapsulation of the region’s post-World War II history. While it lacks the polemic force of Harris, for those that desire such, it does not lack for critique or observation. O’Mara wrote about the book for The Metropole in 2020, which you can read here.

Finally, we conducted a Q&A with Marc Dunkelman regarding his new book, Why Nothing Works: Who Killed Progress – And How to Bring It Back, in November. I normally don’t like big idea books that try to solve complex problems with simple explanations, but Dunkelman really wrestles with the Progressive Era of the 20th century, tracing its influence to today and exploring the contradictions within it that have arguably contributed to our current state of affairs. One can disagree with his conclusions and still draw value from the debates documented in the book. To his credit, he addresses the historiography as well, something books like these often ignore.

Katie Uva

I read a lot of terrific books this year–fiction and non-fiction. Some of my favorites were:

Born in Flames: The Business of Arson and the Remaking of the American City by Bench Ansfield. This meticulous analysis of insurance redlining provides a key lens into the arson crisis that ravaged New York in the 1970s. It also does a great job balancing the more technical, insurance and policy side of the story with the genuine human impact – how people did and didn’t understand what was happening, what it felt like to live through this unfolding catastrophe, and how it has shaped public perception of the Bronx ever since. A great companion to Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor’s Race for Profit and Kim Phillips-Fein’s Fear City.

King of the North: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Life of Struggle Outside the South by Jeanne Theoharis. An important historiographical intervention that reasserts King as militant, radical, and consistently engaged in civil rights battles in northern cities throughout his life. Jeanne Theoharis convincingly argues for the importance of northern struggles in King’s work, has thoughtful analyses of why these parts of his life are typically deemphasized, and has provided an insightful and digestible work that would be good for anyone to read but was particularly helpful to me this year as I reworked classes on New York City History and on America in the 1960s.

Awake in the Floating City by Susanna Kwan. A dystopian novel set in San Francisco in the not-so-distant future (not a genre I usually go for), I was really gripped by this story. An artist who has recently lost her mother to floodwaters is living an unmoored life in increasingly uninhabitable San Francisco–rain is unceasing, much of the population has fled, and the remaining people are living in highrises and travelling across rooftops. I was impressed at the many levels on which the book operated – a meditation on art and inspiration; a story of intergenerational relationships; an incidentally urbanist novel about gradual depopulation and climate change. It was thought-provoking and moving.

Marsha: The Joy and Defiance of Marsha P. Johnson by Tourmaline. Marsha P. Johnson, along with Sylvia Rivera, have been increasingly held up in recent years as the forgotten figures and undeservedly sidelined heroes of the gay liberation movement. This book, the culmination of years of dedicated research, celebrates the life and labors of Marsha P. Johnson and tells us much more about her life beyond the familiar snippets. While her presence at and centrality to the Stonewall Riots is questionable (and Tourmaline is thoughtful about laying out the possibilities), she went on to create S.T.A.R. (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) with Sylvia Rivera, had a sporadic theatrical career in the downtown scene, and was an active organizer and caretaker during the height of the AIDS crisis, even while suffering her own health problems. It’s a powerful, propulsive book and is a great model for a biography that is scrupulously researched, transparently speculative, and firmly rooted in love.

A Gorgeous Excitement by Cynthia Weiner. This novel is set on the Upper East Side in the 1980s, during the Preppy Murders. I thought this was an expert weaving together of that historical event with a well-drawn personal story, of a young woman who is getting ready to go to college and navigating a mix of boredom, restlessness, and anxiety. She spends her time doing cocaine with a new friend, trying to hold her mother’s precarious mental health together, navigating the casual antisemitism of her peers, and trying to catch the eye of gorgeous, aloof Gardner, a fictionalized version of Robert Chambers, the real Preppy Murderer. This is a story that could easily have veered into the shallow or sensational; it’s all the more impressive that it turns out to be a poignant coming of age story and sharp evocation of 1980s New York.

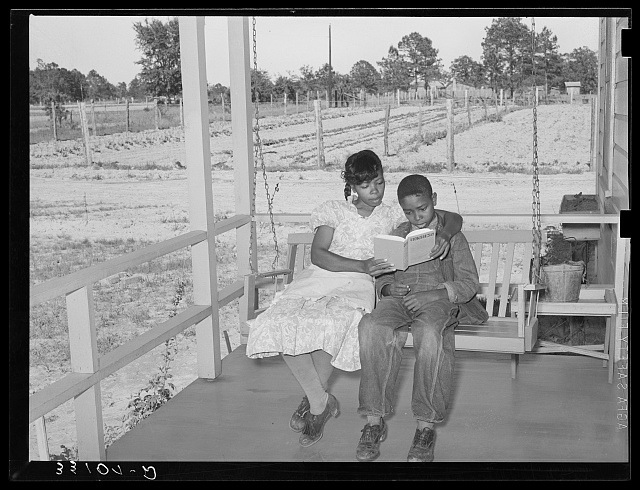

Featured image (at top): Wife of FSA (Farm Security Administration) client reading book to her son on swing on her front porch. Notice garden in background and title of book. Sabine Farms, Marshall, Texas, April 1939, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.