Editor’s note: This is our final entry in The Metropole theme for November 2025, Metropolitan Consumption. To see additional posts on the theme from November, see here.

By Emi Higashiyama

Tokyo epitomizes hunger. A metropolis spanning 2,195 square kilometers and home to 14 million people, the city operates less like an organism and more like a machine–a systematic apparatus of consumption that ceaselessly devours resources and reinvents its landscape. Every square meter seems calibrated for maximum efficiency: commerce, entertainment, innovation, density. Yet at the heart of this metropolitan machine, occupying just 0.7 square kilometers (roughly 0.03% of Tokyo’s total area), stands something that appears antithetical to systematic consumption: a sacred forest where human intervention is largely forbidden.

The forest, however, was entirely manmade. The Japanese language description always refers to it as such with jinnkou (人工 , literally “man made”) because of the sheer coordinated effort of 110,000 volunteers planting 120,000 donated trees from across the Japanese empire between 1915 and 1920. Meiji Jingu, thus, represents the proud national sentiment of the most sophisticated illusion of untouched nature ever engineered. What appears as pristine wilderness is actually precision forestry–365 carefully selected species, arranged according to ecological calculations, designed to create a self-sustaining forest system over the course of a century. This contradiction extends beyond the sacred forest itself. Today, the outer complex (Jingu Gaien) faces fierce civic discord over redevelopment plans threatening the iconic Ginkgo Avenue, the “golden tunnel” that is the very symbol of Tokyo, connecting the present day to Japan’s history of modernization. As with many long-term urban planning projects, and the delicate balance between preservation and progress, Tokyo confronts an identity crisis that is fundamentally an iteration of the same tensions that marked Japan’s entrance into modernity.

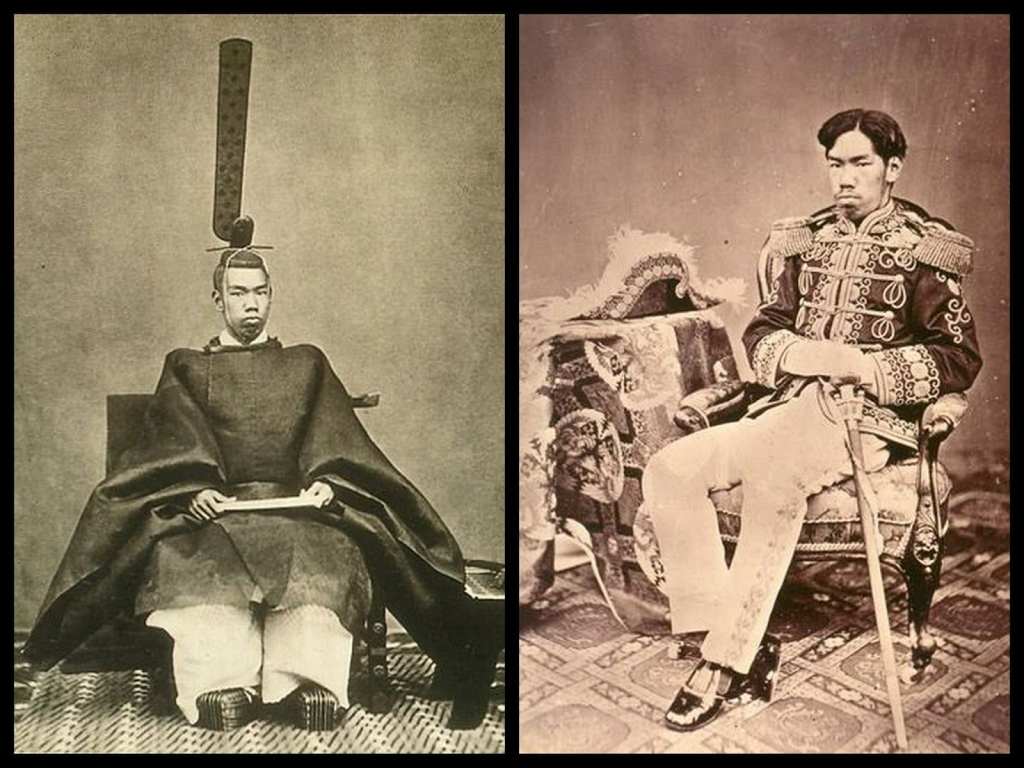

Emperor Meiji became Japan’s sovereign not through natural succession but through calculated revolution. When he ascended the throne in 1867 at age fifteen, he was less an autonomous ruler than a carefully positioned symbol deployed by nationalist forces seeking to dismantle the Tokugawa shogunate, the hereditary military government that had ruled Japan since 1603. The Nativist movement–samurai and court nobles whose philosophy can be summarized as sonnō jōi (尊王攘夷, “revere the emperor, expel the barbarians”)–sought to restore imperial authority and reject foreign influence; the end goal was to overthrow 250 years of military rule, but that would require an imperial figurehead untainted by shogunate corruption and weakness.

The boy emperor was the perfect instrument: young enough to be shaped, prestigious enough to legitimate radical change, and connected to an unbroken imperial lineage going back centuries. What the revolutionary forces called “restoration” was actually systematic transformation – they weren’t returning the emperor to historical power but inventing an entirely new role for him as a central gear in a modernizing state machine. The irony would prove to be profound: Nativists who detested Western influence installed a teenager who would become the primary agent of Japan’s wholesale consumption of Western philosophy, technologies, and systems.

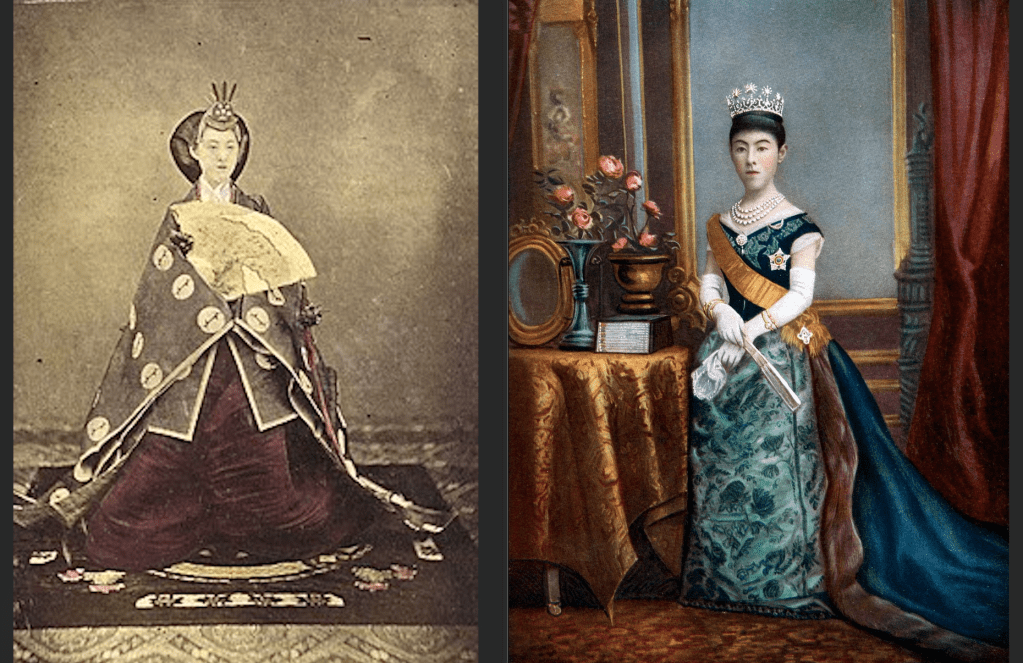

The emperor, arguably a puppet in the earliest years of his reign[1], had the perfect modernizing consort. Said to be a love match, rare for those times, the daughter of an aristocratic family had a strike against her: she was three years older than the emperor. In perhaps a sign of things to come, her official birth year was changed to shorten the age gap, and the ultimate power couple married when he was seventeen years old and she was nineteen (or twenty).

After their 1869 wedding, and throughout their marriage, Empress Shōken shattered centuries of imperial tradition with surgical precision. In a world where empresses generally remained secluded and invisible, she became the first to appear publicly alongside her husband. If that wasn’t modern enough, she also abandoned traditional court dress and wore Western gowns to attend state functions (for everyday fashions, she and her ladies-in-waiting wore Western dress because she said that was closer to what the ancient Japanese wore, whereas the more recent traditional kimono was deemed to be inconvenient for modern life). Her revolutionary acts extended beyond fashion: she championed women’s education, established the Japanese Red Cross, and personally promoted sericulture, the production of silk, as both economic policy and female empowerment.[2] In fact, she started a new tradition: one of the first public events of every new empress since is a televised feeding of silkworms at the Momijiyama Imperial Cocoonery (the silk is mainly reserved for restoring ancient textiles and creating new ceremonial paraphernalia or diplomatic gifts).

Unlike arranged imperial marriages designed solely for dynastic continuity (as it were, Shōken was infertile and would adopt the emperor’s son by a concubine, the future Emperor Taisho), the Meiji-Shōken partnership functioned as political theater. This deliberate demonstration of Japan’s modernization extended into the most sacred imperial institution. They presented themselves as the prime example of a modern couple: complementary, publicly affectionate, jointly committed to national transformation. When both died within two years of each other (the emperor in 1912, the empress in 1914), the nation was confronted with a unique commemorative challenge. This wasn’t simply a matter of memorializing a ruler; this was about honoring a partnership that had embodied Japan’s systematic transformation from isolated feudal state to industrial empire. The solution would require something equally unprecedented: a living memorial as carefully contrived as the modernization they had orchestrated.

The question of how to memorialize Emperor Meiji sparked immediate debate after his death. Traditional options–stone monuments, mausoleums, individual shrine buildings–seemed inadequate for a ruler who had presided over Japan’s comprehensive transformation. Some factions advocated for grand architectural statements befitting an imperial legacy; others pushed for facilities serving public welfare or education. The controversy intensified when Empress Shōken died, creating the need to honor both figures simultaneously, and in a way that would match what they had done: revolutionize tradition itself.

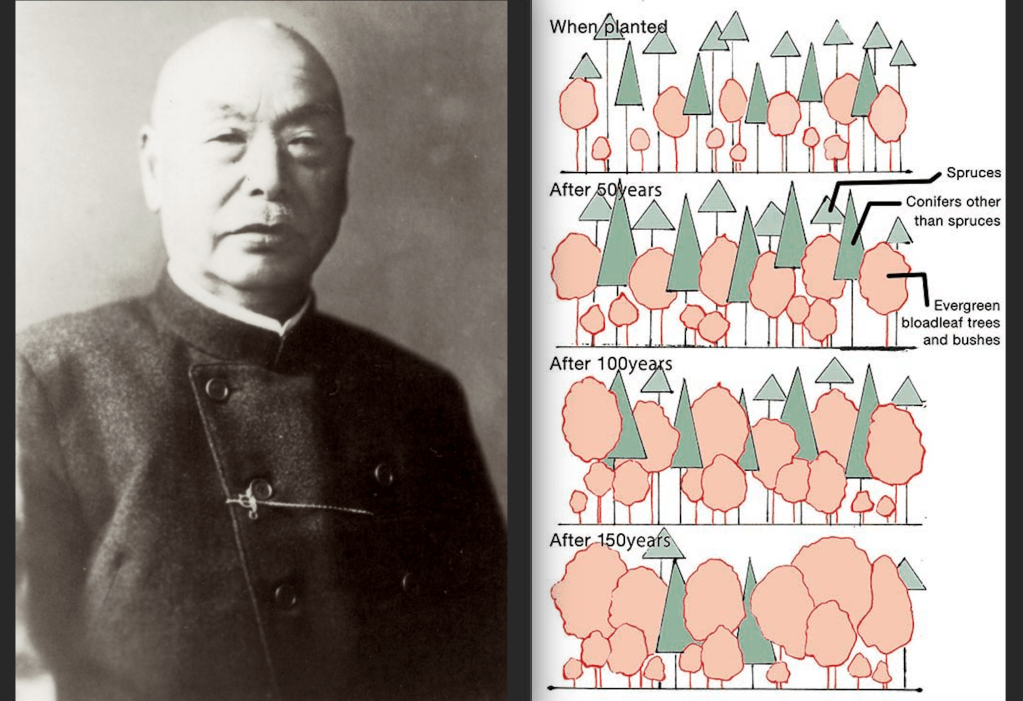

Enter Seiroku Honda (1866-1952), Chief of the Imperial Household’s Bureau of Forestry, whose proposal seemed almost radical: instead of building a monument, why not grow one? Honda had studied forestry in Germany and understood that Japan’s rapid industrialization was consuming its natural landscapes at alarming rates. His vision was audacious, to the point of being unrealistic–creating an entirely artificial forest in the heart of Tokyo that would scientifically be utterly natural within a century. This wasn’t mere gardening or landscaping, it was ecological engineering on an imperial scale. Honda had worked out that 365 carefully selected tree species from across the Japanese empire, planted according to systematic succession principles, would create a self-sustaining forest ecosystem. The plan appealed to multiple constituencies: it honored the emperor’s divine connection to nature through Shinto beliefs, demonstrated Japan’s mastery of Western scientific forestry, and required the kind of national mobilization that would transform mourning into productive imperial service. In 1915, Honda’s living memorial was approved, setting in motion the most sophisticated construction of “natural” space the nation had ever attempted.

Between 1915 and 1920, Honda orchestrated what can only be described as industrial-scale spiritual engineering. A major part of the Meiji restoration was the elevation of the Shinto philosophy into a full-on national religion. This State Shinto policy was, for example, why similar manmade Shinto forests were being constructed in Taiwan, the model colony for the Japanese empire. Official numbers state 110,000 volunteers were coordinated across the Japanese empire, with citizens from every prefecture personally transporting soil and seedlings to Tokyo. Some 120,000 trees (representing 365 species selected for their ecological relationships and symbolic significance) were planted according to precise calculations of projected growth, therefore designed to mimic natural succession patterns.[3] The volunteers didn’t simply dig holes; they were components in a systematic operation that required modern logistics, railway coordination, and bureaucratic organization to create the illusion of untouched wilderness. The forest, once planted, was to have zero human intervention. No pruning, no replanting, no clearing – everyone was supposed to leave it alone for a century, and everyone did. The irony being: a “modern” operation that could only have been possible because the people involved operated from a pre-modern imperial consciousness. Although Japan had become a constitutional monarchy with the Meiji constitution of 1889, the nation continued to behave as if it was under imperial rule. In other words, while democratic in name, the Japanese national character meant that individuals would readily mobilize around the same collective submission to authority that had defined its past. This unity of purpose was less the product of modern democracy than of an inherited, hierarchical will to act as one body in the service of the state. The end result? By 1920, the sacred forest was established, but Honda’s vision extended far beyond spiritual contemplation.

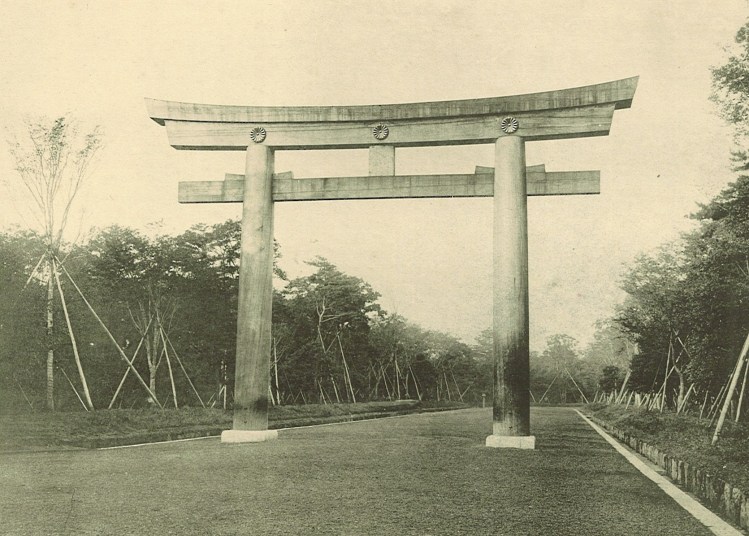

The complex that emerged had an integrated dual system: the Jingu Naien (Inner Gardens) and Jingu Gaien (Outer Gardens). The Naien housed the shrine buildings surrounded by Honda’s engineered forest–a space designated for spiritual worship, ritual, and communion with the deified imperial couple (after death, their spirits would ascend to be on the same level as kami, or the spirits of the natural world that defined the Shinto belief system). The Gaien, completed in 1926, served an entirely different function: physical culture, athletics, and secular commemoration. Here stood the Meiji Memorial Picture Gallery, a series of artwork documenting the emperor’s life, along with baseball stadiums, tennis courts, swimming pools, and most importantly, the ceremonial Ginkgo Avenue that connects the secular and sacred realms. This wasn’t so much contradiction as it was systematic design: the complex served every dimension of modern urban life while maintaining unified imperial purpose (and historiography). The sacred forest, despite its “untouched” appearance, was merely the spiritual component of a comprehensive consumption machine designed to process citizens through carefully calibrated experiences of devotion, recreation, and national identity.

Today, the Naien operates as a space of carefully choreographed spiritual experience. Visitors approach through towering torii gates, stroll beneath the forest canopy Honda engineered, and arrive at the shrine buildings where they can participate in traditional worship–entirely free of charge. Yet the spiritual experience seamlessly transitions into commercial transaction: amulets and talismans bearing promises of luck, protection, and prosperity–all available for purchase at the shrine office. Wedding ceremonies, processed through modern reservation systems, generate substantial revenue while maintaining traditional aesthetics. Restaurants and event spaces operate within the sacred precinct, creating what might be called “sanctified commerce”–commercial activity that derives value precisely from its proximity to the sacred.

The amulets sold in the Naien today represent a curious historical reversal. In the early Meiji period, it was illegal to sell photographs of the emperor because he was considered a divine being and therefore his image was also sacred. However, the government soon began mandating jingū taima–Shinto amulets bearing the emperor’s seal–to be placed in every household as part of constructing State Shinto. Before the Meiji restoration, Shinto was not a codified, doctrinal religion; it was a philosophical world view woven into daily life that involved a set of practices, rituals, and taboos centered around honoring nature and ancestors. At the time of Meiji’s ascension to the throne, the Nativists who masterminded the Restoration had two problems: the anonymity of the emperor (who traditionally lived in seclusion and had no public life) and the zealous efforts to make Shinto a centralized and institutionalized national religion (as opposed to the Buddhism that had already converted most Japanese households). The compulsory distribution of the jingū taima ultimately failed, though the spiritual devotion (in one form or another) managed to survive.[4] Today, those same amulets (or variations of the theme) are sold voluntarily as consumer goods, their purchase motivated not by state coercion but by individual desire for spiritual connection (or simply as souvenirs). What the imperial state couldn’t mandate through systematic control, the modern shrine complex achieves through market forces: the consumption of spiritual objects becomes an act of choice, making the commercial sacred rather than the sacred compulsory. It didn’t hurt that State Shinto, by Honda’s project, had become popular through various grassroots offshoots and that with passing time, became a mix of the people’s tradition, ritual, and spirituality rather than solely imperial ideology.[5]

The Gaien, by contrast, functions as overtly secular infrastructure. The baseball stadium hosts professional games, the tennis courts serve national tournaments, and the Picture Gallery operates as a museum (the creation of which was as involved as the sacred forest). The celebrated Ginkgo Avenue–originally designed as ceremonial passage linking sacred and secular–now serves as backdrop for fashion photography and seasonal tourism in addition to major holiday processions. Modern fitness facilities and sports complexes have been added over decades, each expansion justified as serving contemporary public needs while honoring the Meiji legacy.

The Meiji Memorial Picture Gallery, completed in 1936 as the centerpiece of the Gaien, represented an extraordinary attempt to create public history through visual narrative. The gallery’s eighty paintings depict Emperor Meiji’s life, but really, it’s the story of dueling historiographies. For about two decades, two competing entities, the Ministry of Education and the Imperial Household Agency, were compiling separate biographical works documenting the emperor’s life and his place in Japanese history. The gallery committee chairman, Kaneko Kentaro, presided over topic selection that shifted from imperial biography to comprehensive national history, which then translated into artwork that involved historical investigations over “real” history and “realistic” painting. The result was the first form of officially sanctioned national historiography available to the public–years before written chronicles were published.[6]

The evolution in how imperial images circulated reveals a striking transformation in the relationship between emperor and subjects. In 1875, a photographer and his client were arrested for secretly trafficking copies of Emperor Meiji’s portrait. The government was terrified that uncontrolled circulation would damage the carefully constructed imperial mystique. An opinion piece in an opposition newspaper at the time accused the government of “robbing the wishes of good citizens to know the appearance of their sovereign.”4 Today, the royal family appears routinely on calendars, newspapers, and social media feeds, their images consumed as freely as any celebrity’s. It’s as if the population has inverted the power dynamic entirely with its consumptive power: where once the emperor owned his image absolutely, now the people treat the royal family as public property to be photographed, discussed, and commodified at will.

In 2022, the announcement of a massive redevelopment project for Jingu Gaien ignited fierce public opposition that revealed how profoundly contemporary Japanese citizens have internalized a sense of ownership over what was once imperial space. The development plan–a collaboration between Mitsui Fudōsan, Meiji Jingu, and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government–proposed demolishing the aging National Stadium facilities and constructing new high-rise buildings, luxury hotels, and commercial complexes. Most controversially, the project threatened to fell dozens of trees along Ginkgo Avenue, the ceremonial pathway that Honda Seiroku had designed to funnel people from the secular Gaien into the sacred Naien. Public outcry was immediate and passionate. Preservationists launched petition campaigns that collected hundreds of thousands of signatures. Protesters held demonstrations insisting that the Gaien belonged not to the developers or even to Meiji Jingu as an organization, but to the citizens of Tokyo (or, to the nation as a whole). The trees, they argued, were not mere landscaping but living monuments, part of the century-old ecological system that Honda had engineered to mature over generations. Environmental groups calculated that the development would destroy approximately 3000 trees across the complex, fundamentally altering the character of what many considered public heritage space.

The intensity of the opposition reflects a curious historical reversal: the outer precinct that Honda and the Meiji Shrine Support Committee built through public donations and volunteer labor (thanks to imperial governance and culture) has become, in the modern public imagination, a genuinely public space, despite its private ownership by Meiji Jingu as a religious corporation. What began as systematic imperial commemoration has transformed into democratic commons. Citizens now claim the right to determine the Gaien’s future precisely because they no longer view it as belonging to any sovereign authority but to themselves as collective inheritors of a shared national legacy.6

The Gaien redevelopment reveals how thoroughly Japan’s top-down city planning system–established since the Meiji period as a national project to build Tokyo into a capital befitting a modern country–continues to operate through deregulation that favors large-scale private development. The Olympics have repeatedly served as a catalyst for this consumptive nation-building. The 1964 Summer Olympics, the first held in Asia, symbolized Japan’s return to the international stage following its loss of dignity after World War II and being forced to endure American occupation afterward. Massive infrastructure projects like the Shinkansen bullet train and Metropolitan Expressway were rapidly constructed at the cost of heavy environmental and labor burdens, but the dramatic transformations were worth the price tag. The 2020 Summer Olympics (postponed for a year due to COVID-19) provided similar justification for large-scale redevelopment – affirmation that Japan was indeed a significant player on the global stage.[7]

But as is often the case with outward-facing policies, the inner workings of the policy development have been mired in conflict. Reports surfaced that Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG) had been orchestrating the Gaien redevelopment plan as early as August 2011, holding behind-the-scenes meetings with former Prime Minister Yoshiro Mori and various politicians before any public announcement. Leaked TMG documents revealed that regulations had been manipulated to relax height restrictions and adjust zoning ordinances so that public park land could be yielded to private developments and facilitate tree removal. When confronted about various inconsistent statements over the years, TMG officials downplayed the significance of the content and oversimplified the situation as “lacking politeness” (Japanese social code that covers a multitude of sins), all while insisting their lobbying was fully legal and legitimate.

The official project website presents a buoyant narrative, emphasizing that the redevelopment will “carry on the legacy and wishes of our predecessors” with the end result of world-class sports facilities and revamped landscape. It promises to enhance disaster (namely, earthquake damage) prevention, improve accessibility, and “sustainable urban development” with more green space. There is little or no mention of the hundreds of elderly households facing eviction (in some cases, for the second time), the elimination of baseball fields and tennis courts used by ordinary citizens, or the fact that the “green space” consists of luxury hotel rooftop plantings replacing grand old trees at street level. Public outcry, augmented by famous culturists like novelist Murakami Haruki and composer Sakamoto Ryuichi, had gained momentum to the point where the Tokyo governor was nicknamed the “Empress of Tree-Cutting”–but the unpopular redevelopment plan is full steam ahead. Construction began in October 2024, with adjustments to the tree count (by the end of the project, the total number will be even more than what it was pre-redevelopment), a new baseball stadium built farther away from Ginkgo Avenue, new skyscrapers that house commercial and residential activities, as well as renovations to various sports facilities.

Meiji Jingu embodies the central paradox of Japan’s modernization–a sacred forest built by an imperial machine to commemorate the very emperor who transformed Japan into that machine. In a city built for consumption, the Meiji Jingu complex reveals how even anti-consumption becomes systematically consumptive. The current redevelopment controversy isn’t a departure from the forest’s original purpose but rather its inevitable fulfillment: what was created to serve the imperial state must continue serving the modern state’s evolving needs, even when preservation itself becomes the new form of systematic control.

Tokyo epitomizes consumption in its most sophisticated form: a metropolitan machine that processes 14 million residents through systems of efficiency that enable unparalleled prosperity, innovation, and convenience. Its citizens benefit enormously from this apparatus that seamlessly combines reliable infrastructure, abundant commerce, and cultural dynamism–the very mechanisms that make urban life functional. Yet the machine’s success generates its own contradiction. As Tokyo consumes every available square meter for optimization, its population develops a corresponding hunger for what the system eliminates: untouched nature, inefficient green space, and trees that serve no obvious utilitarian purpose. As a sacred forest and therefore protected from human interference, Meiji Shrine forest has inadvertently become a sanctuary for flora and fauna. In a 2011 survey to prepare for the artificial forest’s 100th anniversary, some rare (and endangered) species were discovered to be flourishing within the sacred precinct–an unintended ecological triumph that Honda’s systematic planning could not have predicted. Yet these trees serve no purpose beyond existing. They produce no lumber for construction, generate no measurable economic value, address none of the climate imperatives that dominate contemporary environmental discourse. Honda could not have anticipated carbon sequestration, urban heat island effects, or air quality indices; these concepts didn’t exist when he calculated his forest’s succession patterns in 1915. The trees simply exist, protected by their sacred designation, valuable precisely because they remain unconsumed. Herein lies the forest’s most profound lesson: that a century-old machine designed to commemorate imperial power has generated something that the machine never intended: a space where nature operates outside systematic purpose, where inefficiency itself becomes the highest form of value in a city that cannot stop consuming.

Honda’s century-old vision continues to inspire. The Ōtemachi Forest, completed in 2012 in Tokyo’s financial district, deliberately mimics Meiji Jingu’s ecological engineering: transplanting mature trees to create instant “natural” woodland nestled among skyscrapers, designed to mature over another century into self-sustaining ecosystem. It represents the same systematic approach of nature as carefully managed component of a machine, or wilderness as urban amenity; depending on how one looks at it, a real fake forest (or a fake real forest). While it’s possible to inject pockets of manufactured nature into cities, it remains impossible to introduce urban life into genuine wilderness without obliterating what makes it wild. As Tokyo satiates one hunger through relentless consumption, it paradoxically generates hunger for its opposite, proving that even the most efficient machine cannot eliminate the human need for what lies beyond systematic control. The forest Honda built continues teaching this urban lesson: that what we hunger for most is precisely what our hunger destroys.

Emi Higashiyama is a freelance writer who writes about architectural history. Higashiyama contributed to The Metropole’s recent theme months, The City Aquatic and Los Angeles, and was a participant in the 2024 Graduate Student Blogging Contest.

Featured image (at top): The unmistakable entrance to every Shinto shrine, a torii (literally “bird house”). The Grand Torii of Meiji Jingu – standing 12 meters tall and built out of 1500-year-old Taiwanese cypress– kills two birds with one stone: being the tallest torii in Japan and built with timber from its most successful colony. 1920 photo courtesy of Meiji Jingu; undated 2020s photo at the conclusion of the essay directly above is courtesy of Rakuten Travel

[1] Donald Keene, Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002).

[2] Mamiko C. Suzuki, Gendered Power: Educated Women of the Meiji Empress’ Court, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2019).

[3] Yoshiko Imaizumi, Sacred Space in the Modern City: The Fractured Pasts of Meiji Shrine, 1912-1958, (Leiden: Brill, 2013).

[4] Maki Fukuoka, “Handle with Care: Shaping the Official Image of the Emperor in Early Meiji Japan,” Ars Orientalis 43 (2013): 108-124.

[5] Shimazono Susumu and Regan E. Murphy, “State Shinto in the Lives of the People: The Establishment of Emperor Worship, Modern Nationalism, and Shrine Shinto in Late Meiji,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36 (2009): 93-124.

[6] Yoshiko Imaizumi, “The Making of a Mnemonic Space: Meiji Shrine Memorial Art Gallery 1912-1936,” Japan Review 23 (2011): 143-176.

[7] Junichi Hasegawa, “Redeveloping Tokyo’s Meiji Jingu Gaien Area: The Metropolitan Government’s City Planning Runs Amok,” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 23 (2025): 1-14.

Thanks for calling attention to Seiroku Honda, the glories of the gingko and the struggle to save a man-made urban forest. Shall we call Honda the ” Olmsted of Japan?” One wonders how the forest survived the war. The lindens of Berlin did not do well.

LikeLike