Editor’s note: This is the fourth post for our November theme month, Metropolitan Consumption. You can see additional posts from the month here. See also David Bruno’s piece here from The Metropole’s 2024 Graduate Student Blogging Contest.

By David Bruno

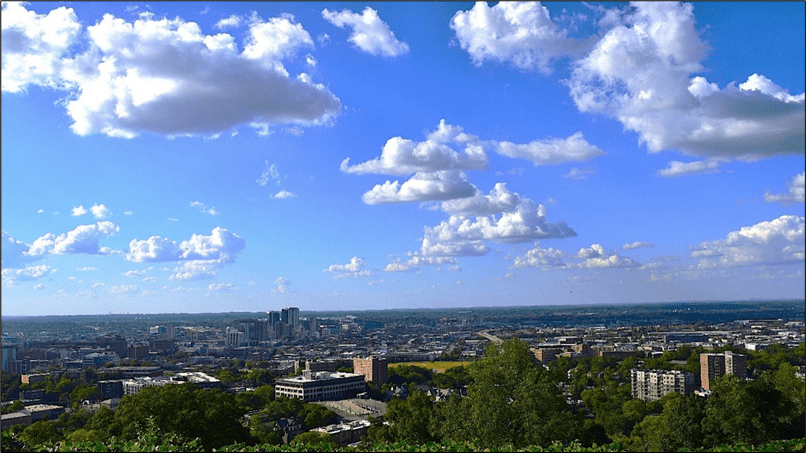

Rising from the ashes of the Antebellum South, Birmingham, Alabama, went from undeveloped land in 1871, to an industrial powerhouse that represented the best of the New South by the early twentieth century. The city reflected modernity, especially through its neoclassical skyscrapers and industrial economy. By 1971, the opposite was true; the city was mired in its Jim Crow past, and its industrial economy was quickly declining. Its racial issues and economic structure exemplified the past.

Characterized as “this magic little city” by one of its founders, Col. James R. Powell, Birmingham during its boom years adopted the moniker “The Magic City.”[1] It earned another nickname during the Civil Rights Movement. Violent white resistance including police brutality, frequent bombings, and the murder of four young girls in the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing popularized the name “Bombingham.” While the city is no longer “Bombingham,” it experienced a rapid decline post-1960s. Its fall was an inversion of its rise a hundred years prior. By the 1990s, Birmingham was defined by white resistance and economic desolation brought about by the collapse of the steel industry.[2] At the same time, cities across the country shifted their economic focus toward the rising service economy. Cities approached the service economy by selling an experience. For example, a typical downtown entertainment district includes restaurants, shops, and music venues that share a common goal of providing visitors with an enjoyable experience. Major job sectors in this area include retail, marketing, and hospitality. Across American cities during the late twentieth century, acquiring an intangible experience and urban identity became a popular form of consumption. This included southern cities.[3]

Nashville serves as one such example as it successfully revitalized its economy through the service sector. By aligning its image with its entertainment venues and areas, such as the Broadway Street corridor, Nashville rebranded as a destination city. Building on its history as the center of country music, Nashville successfully reoriented itself around heritage tourism and entertainment. With the addition of an NFL and NHL team, by the 2010s it had emerged as both a tourist destination and as a premium market for young professionals, families, and creative types to relocate. In contrast, Birmingham lacked a similar cultural tradition or entertainment attractions upon which to market itself. It needed to make up for this deficit, and after several major attempts, the city failed to achieve this. Its story highlights the challenges facing cities in the service economy, where a brand and tourist consumption is critical for success. The competition for tourism creates winners and losers, with average mid-sized cities such as Birmingham often on the losing end.

Emerging as first a savior, and later the man responsible for driving the city deeper into economic despair, was a charismatic politician with a penchant for sweets and cigarettes named Larry Langford. Langford rose to prominence in the 1990s as the most aggressive fighter of Birmingham’s urban crisis. He was a television reporter turned politician, becoming Fairfield’s first Black mayor in 1988 (Fairfield is a small city adjacent to Birmingham). At the turn of the century, Langford was elected as a member of the Jefferson County Commission, serving one term as president, then mayor of Birmingham from 2007-2009. During Langford’s time in public life, he proposed and attempted a bevy of projects that ranged from the practical to the preposterous. This article will focus on three of his most ambitious plans.

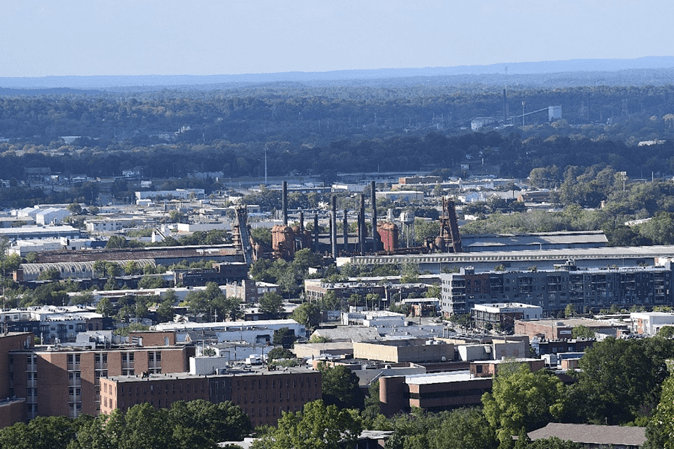

Even as mayor of Fairfield, Langford became the savior of Birmingham. During the 1970s and 1980s, US Steel, a major employer in Birmingham, downsized, imparting economic devastation and contributing to political dysfunction. Langford crafted a plan to build a regional theme park in the Birmingham metro area called VisionLand. Arguably the most successful of his bold plans, Langford defied the odds when he opened the park in the summer of 1998.

VisionLand was originally conceived as part of a broader entertainment area that included an aquarium, hotels, restaurants, and an outlet mall. Langford wanted to “make Alabama a complete destination point.”[4] Self-determination was at the heart of the project; it was an opportunity for Fairfield to do something for itself. Langford did not want to attract an established company to build the park and operate it; he wanted it publicly owned—an aspect of this was his desire to control the project. Langford clapped back at those questioning his refusal to lure a theme park company through tax incentives and public funding saying, “If they’re so in love with us then why do we have to pay them to come here?”[5] He wanted Fairfield residents to control their own destiny. Langford said that VisionLand “should diversify us to a point to where a downturn in the economy will not put us in position where we have to suffer again what we went through in the 60s and 70s.”[6] Langford also wanted an entertainment space for his constituents. He said that the idea came to him after realizing that anytime his family wanted to do something fun, they had to leave the state. He complained, “The only reason to visit Alabama is if one of your relatives died.”[7]

The park was a joint venture between eleven municipalities across Jefferson County and west Alabama, including Birmingham. Langford was a master salesman, convincing the partnering municipalities that the project would bring them an influx of wealth. He argued that “VisionLand is going to bring much needed jobs to the area.”[8] With joblessness and poverty rates skyrocketing, the ambitious plan was more than appealing. The group formed the West Jefferson Amusement and Public Park Authority and purchased 300 acres of land in Bessemer—one of the eleven cities. Langford was placed as chairman of the board. Ultimately, his domination of the project influenced its downfall.

VisionLand was distinctly Langford’s. He expressed an almost evangelical zeal suggesting the park was ordained by God and that he feared not giving God enough credit for it. He had the word “God” engraved in brick throughout the park—despite this fact, it was nominally a secular park. Further reflecting Langford’s piety, the park’s name derived from Proverbs 29:18, “Where there is no vision, the people perish.”[9] Reporters mocked the name for sounding more like an optometrist practice than a theme park.[10]

A key ambition of Langford’s was to change the image of the Birmingham metro area. He believed that “Our racist past continues to threaten our future.”[11] Langford hoped that VisionLand could alter perceptions and even improve race relations.[12] In this context, Langford and the city imagined it as a symbol of racial unity and what can be achieved when whites and Blacks work together. Langford championed the park’s integrated staff to the press and said that he wanted visitors to notice the staff. He also highlighted depictions of racial unity by having them sculpted into a brick wall behind a carousel and stressed that he wanted visitors to see the wall.

VisionLand’s opening day in 1998 marked the zenith of Langford’s career; the park’s establishment and opening made Langford a rising star. He brought a theme park to a desolate part of Alabama when the idea was universally considered impractical.[13] Langford was talked about as a gubernatorial candidate and he even boasted that he might run for president in the future.[14] VisionLand, however, quickly went south.

The confused nature of the park was a factor in its downfall. It was both a water park and an amusement park, with ticket prices being the same for both sections. The entrance, called “Main Street,” was designed to mimic a small town on the Fourth of July, with souvenir shops and restaurants lining the street. The water park section was named “Steel City Waterpark.” Its industrial-themed slides and tubes were designed to pay homage to the area’s industrial heritage. This section of the park included a tube slide named “The Mine Shaft,” and a souvenir store named “Iron ore Treasures.” The theme park section was less focused on industrial motifs. It was comprised of standard rides such as a rollercoaster. Contributing to the park’s disjointed identity, it opened Dino Domain after its first year. The attraction was comprised of 36 life-sized dinosaurs, a large portion of which were animated, in a wooded area. Dino Domain costs $2.5 million. It closed after a year because it failed to attract enough visitors, leading to major financial difficulties for VisionLand.

The park’s first year was a modest success, but subsequent attendance did not meet expectations. After four years of operation, VisionLand was unable to pay its creditors and bondholders. In 2002 the park declared bankruptcy. As part of the bankruptcy agreement, Langford stepped down as chairman and the park was sold for $5.2 million, after the eleven municipalities had invested more than $100 million into VisionLand.[15] VisionLand was renamed and still exists today as Alabama Adventure and Splash Adventure.

Prior to stepping down as chairman, Langford worked extensively towards making the aquarium a reality. Named VisionQuest, the concept was modeled after the Tennessee Aquarium in downtown Chattanooga, Tennessee. Langford wanted dolphins, whales, and an arena that could seat 1,000 people for shows. The plan stalled due to VisionLand’s financial difficulties and when Langford discovered that ocean wildlife was not cheap. The price of two dolphins was $750,000 and the best price he could find for a whale was $2.4 million. “At that price they better be able to operate a computer and drive a car,” Langford remarked incredulously. While VisionQuest never materialized, Langford continued advocating for an aquarium during the remainder of his political career. As mayor of Birmingham, he made another push. He was convinced that a downtown aquarium would revitalize Birmingham. During a radio interview Langford uttered his most famous line, “If Atlanta can have beluga whale, we can have one too.”[16] The aquarium was never built.

Despite VisionLand dimming his political star, Langford continued to propose innovative ways to turn Birmingham into a destination city. His most bombastic plan dwarfed VisionLand in boldness. Adopting elements of a plan conceived by another mayor, James Van Hoose, in the late 1890s, Langford proposed to connect Birmingham to the Black Warrior River through a series of reservoirs, linking the city to the Gulf of Mexico.[17] “Only 20 miles are separating us from the rest of the world,” Langford said. The proposal called for a 4.5 square-mile reservoir and harbor located near the former US Steel Ensley site. Langford saw infinite potential in the plan. He envisioned the reservoirs as sites for recreational boating and riverwalks based on San Antonio’s.[18] At minimum the plan would cost a billion dollars. The reception for the canal was mixed. Some found it amusing, while others championed Langford for his creative vision. The fact that Langford’s political career improved after the proposal is indicative of the admiration that the city had for him as an out-of-the-box thinker who was doing more than anyone else to improve the city. Some observers even said that Birmingham needed more Langfords.[19] The canal was arguably Langford’s most notorious proposal; long-time residents still talk about the plan, joking at its absurdity while fondly remembering the surreal leadership of Larry Langford.

Waterparks, aquariums, and canals aside, Langford’s time as mayor of Birmingham was dominated by his unrelenting quest to build a domed stadium. A stadium for sporting events and concerts is imperative for any budding-destination city. Birmingham’s urban crisis was exacerbated by the loss of the University of Alabama’s football games. Despite the university being forty minutes away in Tuscaloosa, for decades Alabama played its home games at Birmingham’s Legion Field. Additionally, until the early 1990s, the annual rivalry game between Alabama and Auburn—the Iron Bowl—was also played at Legion Field. Arguing that it was not a neutral site, Auburn moved its Iron Bowl home games to its campus. A few years later, Alabama made a deal with Tuscaloosa, Tuscaloosa County, and Druid City for $4.5 million to expand its campus stadium in return for no longer playing games at Legion Field.[20] As a consequence, Birmingham lost another economic mainstay, deepening its downward trajectory.

Birmingham was also rapidly losing events such as college basketball games and conventions. A determining factor was the city’s convention center that desperately needed renovations. Commenting on the issue, a domed stadium supporter said that Birmingham was in competition with Montgomery, Mobile, Huntsville, and Chattanooga for convention business. They added that “A few years ago, we wouldn’t have considered them our competition. We used to compete with Nashville and Charlotte.”[21] The dome was the catchall solution to these problems—it simultaneously offered a sporting venue and convention center. Langford firmly believed that “if he builds it, they will come.”[22] This included an NFL team, concerts, and shows. In Langford’s mind, Birmingham just needed one major attraction to turn the city around.

Like VisionQuest and the canal, the dome was never built. Langford failed to generate enough popular sentiment and financial backing. Funding such a large project would have been difficult for the city, and after the 2008 financial crash, it was impossible.

Further polarizing his already storied legacy, in 2009 Langford was found guilty of accepting bribes for influence regarding sewer bonds and sentenced to fifteen years in federal prison. His corrupt dealings created $3.5 billion in sewer debt, causing the largest municipal bankruptcy in world history at the time. Jefferson County citizens are still paying for it. While in prison, Langford fell critically ill and was given a compassionate release. For the last time, he returned home to the Magic City where he passed away in 2019. An undoubtedly enigmatic figure, Langford’s efforts reveal the struggle that some cities faced when trying to reorganize their economy after industrial decline. His impractical yet impassioned ideas were reflective of the impossible situation many communities were put in when deindustrialization began. His story also highlights trends of transforming downtown areas into entertainment districts aimed at attracting tourists and suburbanites. In a sense, his plans provide insight into the trend of cities catering towards outsiders, courting their consumption by transforming urban landscapes into entertainment playgrounds. Birmingham’s struggle to become a destination city is symbolic of a larger struggle that mid-sized cities in the United States continued to experience with the effects of deindustrialization, globalization, and inter-city competition.

David Bruno was born and raised in Birmingham. Larry Langford’s plans are a good microcosm for his experience living here—a cycle of hope that the city will live up to its Magic City moniker, followed by disappointment. However, the city has made a lot of small changes since the 1990s and is a much better place. But as Langford said, it is still haunted by its past. Like many long-term residents, Bruno has mixed emotions about Birmingham. Bruno is a PhD student at the University of Mississippi (Ole Miss). His work concentrates on urban revitalization and the urban crisis, with a special focus on neoliberalism, labor, and the carceral state. His dissertation is tentatively titled: The Safest Shopping in the World: Revitalizing South LA through High-Security Malls. Interested readers can see a post from the 2024 Graduate Student Blog Contest that speaks to this research here. Feel free to contact him at dpbruno25@gmail.com.

Featured image (at top): Mayor Larry Langford, May 12, 2005, photo by Bhamadvisor2, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

[1] Tabitha Slawson, “How did City get its Magic,” Birmingham Post-Herald, October 8, 1987.

[2] By the 1980s, Birmingham was a majority Black city with a Black mayor; white migration to the suburbs created a distinct dividing line between the Black city and the white suburbs.

[3] Hal K. Rothman, Devil’s Bargains: Tourism in the Twentieth-Century American West (Lawrence: University of Kansas, 1998) 368.

[4] Linda Long, “Developer has Vision for State Aquarium,” The Huntsville Times, May 9, 1999.

[5] Nick Patterson, “VisionLand will be Reality,” Birmingham Post-Herald, August 31, 1995.

[6] Veto Roley, “Fulfilling a Vision,” The Selma Times-Journal, February 27, 1998; In From Steel to Slots: Casino Capitalism in the Postindustrial City Chloe E. Taft discusses a similar case in which the formerly industrial city of Bethlehem, PA transition to a service-oriented economy through turning a former factory into an industrial themed casino. Bethlehem experienced more success than Birmingham.

[7] Nick Patterson, “VisionLand will be Reality,” Birmingham Post-Herald, August 31, 1995.

[8] Veto Roley, “Fulfilling a Vision,” The Selma Times-Journal, February 27, 1998

[9] Phil Pierce, “Larry Langford’s Promised Land Reflects his Values,” Birmingham News, May 21, 1998.

[10] John Archabald (long-time Birmingham area journalist) in discussion with the author, September 2025; Phil Pierce, “Larry Langford’s Promised Land Reflects his Values,” Birmingham News, May 21, 1998.

[11] Handwritten note by Larry Langford, Miscellaneous Langford Records, Birmingham Public Library Special Collections.

[12] Dave Casey, “VisionLand attracts Private Investment,” Mobile Register, December 7, 1997.

[13] Bob Johnson, “Fairfield Mayor Did Lots More Than Talk,” Birmingham Post-Herald, May 21, 1998.

[14] Michael Sznajderman, “Langford Says He Will Run for Statewide Office in 2002,” Birmingham News, August 18, 1998.

[15] Associated Press, “VisionLand is Bankrupt,” Daily Sentinel, June 6, 2002.

[16] Recorded audio from WJOX 94.5 FM, “Funny Montage of Wacky Larry Langford sayings…,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lb4YMSWqwO8.

[17] “Going North: While There Ex-Mayor Van Hoose will Look after the Canal,” Birmingham News, January 11, 1897.

[18] Paul Foreman, “Birmingham-to-Gulf Link Pushed,” Birmingham News, March 10, 2000.

[19] Tom Scarritt, “It’s too Easy to Scoff at Big Dreams,” Birmingham News, March 19, 2000.

[20] Richard Powell, “Stadium Deal Gets Approval,” Tuscaloosa News, September 15, 1995.

[21] Kim Chandler and Stan Diel, “Langford’s Dome Plan Takes Form,” Birmingham News, November 25, 2007.

[22] John Archabald (long-time Birmingham area journalist) in discussion with the author, September 2025.