Editor’s note: In anticipation of what we all believe will be a stellar UHA conference this October 9-12 in Los Angeles, we are featuring Los Angeles as our theme this month. This is our first piece, you can see others from this month as they are published as well as past pieces on the city here and check here for info on the conference including accommodations.

“Sunshine or noir?” as the late, great Mike Davis famously asked of Los Angeles. “Sunshine” serves as “the boosterish impulse to frame the city as a white Anglo-Saxon paradise, all palm trees and pristine coast and limitless potential for success, wealth, and glamor,” Jack Hamilton wrote, exploring this dynamic in a 2022 remembrance of Davis. “‘Noir’ is, effectively, the rejection and critique of this tendency; the artists and thinkers that Davis categorized as noirs believed that what is superficially promised by the sunshine proponents in fact is just a veneer over vicious exploitation, injustice, and inequality.” The dichotomy certainly captures some of the city’s essence–-a municipality bathed in light, but with a strong undercurrent of darkness.

To be fair, Davis’ Marxism, one might argue, leads him to dialectics such as the sunshine/noir juxtaposition that some even admiring critics find limiting. In a review of Jon Wiener and Mike Davis’ Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties, The Metropole recounted historian Eric Avila’s critique of Davis:

“There is a rigorous adherence to this binary: no in-betweenness, no ambivalence,” historian and Los Angeles writer Eric Avila noted in a 2010 essay. “Class war is not a means, but the means of understanding Los Angeles’ history.” Ethnic identity, race, geography, sexuality, gender, and numerous other factors “that mediate social relations are secondary iterations.” For Avila, Davis’s pessimism reigns too prominently: “Lesson: Hope is futile. Mike Davis’s Los Angeles devours our aspirations, consuming our collective dreams along with the desert land.”

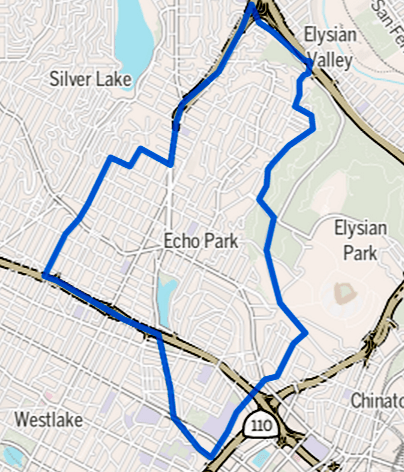

Criticism acknowledged, and the reductive nature of binaries noted, Davis’ “Sunshine or Noir?” still serves as a means for understanding this month’s L.A. theme. Within this framing, one might suggest the city’s Westside, most famously Hollywood and places like Beverly Hills and Santa Monica which are not actually in Los Angeles but often aggregated as such, operates as the sunshine, while its Eastside, neighborhoods like Silver Lake and Echo Park, form its noir.

In recent years, Silver Lake has gotten more than its share of shine. Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons published Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics and Lipstick Lesbians (2006) which highlighted its role in creating space for Los Angeles’s gay and lesbian communities. Daniel Hurewitz followed with Bohemian Los Angeles: The Making of Modern Politics(2008), a work that delves into Silver Lake’s role in the creation of the Mattachine Society and how it shaped the formation of identity politics.

In Bohemian Los Angeles, Silver Lake (known as Edendale during the 1930s) serves as the book’s key setting, a space where communists, artists, and homosexuals resided within each other’s orbits and reached a certain equilibrium of politics, sexuality, and sociability very much apart from the conservative currents of the city during that era. More recently, Under the Silver Lake (2018), a neo-noir starring Andrew Garfield as a pathetic nostalgia-addicted hipster trying to chase down a fever dream of a girlfriend furthered, somewhat controversially, its bohemian reputation for a new generation.

But what about Echo Park? You’ve undoubtedly seen its famous lake, Echo Park Lake, at some point in film–-it’s featured in Under the Silver Lake as well as Chinatown (1974)–but its history and culture have not drawn as much attention.

The lake, actually a reservoir named Reservoir #4, was part of a larger attempt to provide drinking water to the city’s eastside, but in actuality served as a means by which to spur real estate development. Purchasing land directly across from the reservoir, Thomas Kelley and five partners divided the purchase into lots and then placed them on the market for sale.[1]

Built by the Los Angeles Canal and Reservoir Company, the reservoir sat below the Arroyo de Reyes. The company “dug a long, serpentine canal between the Los Angeles River and the reservoir site, and then flooded the ravine with the diverted water. Once filled, the reservoir became the largest body of water within the Los Angeles city limits,” noted Nathan Masters in 2014.

The economic development, however, never came, in part because it turned out the reservoir was a flood hazard. In 1892, the company, in exchange for 33 acres elsewhere in the city, donated the reservoir to the city for development as a park. City park superintendent and landscape architect Joseph Henry Tomlinson named it Echo Park and went about transforming the reservoir into a proper public space, completing the lake in 1895. By the following year, the Los Angeles Times, a noted booster of the city, promised that the park would soon be “one of the most beautiful spots in Los Angeles.”

The park and its lake served as its first neighborhood anchor. Later Aimee Semple founded her Angelus Temple, arguably the nation’s first megachurch, in Echo Park, drawing international attention. The addition of the city’s electric railway in the early 20th century further contributed to the community’s development and did so into the late 1940s, when highways replaced the once vital transit system.

University of Southern California professor Natalia Molina and her mother, Maria, grew up in Echo Park, the latter working often at her mother’s restaurant, the Nayarit. When Molina’s grandmother immigrated to the United States in 1922, Natalia Barraza aka Doña Natalia settled in Los Angeles. Echo Park around that time had garnered a reputation as being “diverse and progressive,” writes Molina.[2]

During the 1920s, the neighborhood had blossomed into a “downtown suburb” where creatives lived: architects, printmakers, artists, and Hollywood studio executives, among others. In the 1930s and 1940s, it earned a reputation for vibrant leftism. Numerous HUAC-blacklisted writers called it home, as did a chapter of the Civil Rights Congress, which held strong communist affiliations. Union activists and organizers also claimed the community.

The neighborhood’s political and social orientation enabled personal and cultural bonds that could transcend race and sexuality, as both Silver Lake and Echo Park have long been LGBTQ-friendly. These cultural and personal bonds provided immigrants and others with some level of actual social mobility.

Molina’s 2022 book, A Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a Community, explores the Nayarit’s place in the community and how it encapsulated and amplified “the values of mutuality, public sociability, and collectivity” in Echo Park. The Nayarit, which opened on Sunset Boulevard in 1951, serves as a window into Echo Park’s mid-20th century culture and its unique and underrepresented place in the city’s galaxy of neighborhoods.

Echo Park’s lack of planned development might be why it never adopted any strict racial housing segregation. No historical record exists explaining why this occurred but as Molina points out “as a rule…aggressive policing of the color line did not take place in Echo Park.” One sees this beyond housing in its local institutions. The Nayarit, as will be discussed, welcomed all and though Angelus Temple congregations tended to be mostly white, it included small numbers of African Americans and ethnic Mexicans, thereby providing “community in a world that pushed them to the margins,” observes Molina.[3]

Doña Natalia opened the original Nayarit near Boyle Heights, where it operated for several years before opening what would become its institutional location in Echo Park. When she settled there in the early 1950s, nearly 80 percent of the community was white, but mostly immigrants from Southeastern and Eastern Europe, the not quite white “white ethnics” of the early 20th century. Latinx residents, mostly of Mexican ancestry, were another 16 percent. Like many other communities, Echo Park did not escape white flight. Driven largely by federal housing policies established during the 1930s, notably the HOLC and FHA’s redlining, and furthered by private lending practices, Echo Park’s diversity was ultimately penalized. By 1970, Latinx residents made up 52 percent of the community and though still diverse, it became less so. Finally, a small Asian population resided in the southwest portion of the neighborhood. Due to its aggregation of Filipinos, it was referred to as Little Manila. In 2002, it was officially designated as Historic Filipinotown.[4]

“Echo Park was an incubator that fostered relational notions of race,” in which different racial and class groups made connections that helped them “better understand the logic that underpins the forms of inclusion and possession they face,” notes Molina. The Nayarit existed as a public expression of this reality. “The placemaking that went on at the Nayarit, was both convivial and political,” writes Molina. If Mexican workers spent their days trying to minimize their visibility, they could unwind at the restaurant: “customers could become visible, speak out, and claim space; they could unfold their true dimensions. They could belong.” Spanish rang out in the Nayarit, an empowering aspect of the restaurant’s culture that enabled for what Theresa Gay Johnson calls “spatial entitlement.”[5]

Clientele, though frequently Latin American, was hardly uniform. The restaurant “welcomed everyone from the neighborhood residents and white leftists to downtown white-collar employees on a lunch break and hungry people across the city.”[6] Famous actors, athletes, and musicians, Latin American and American alike, also frequented its tables; Marlon Brando, Rita Moreno, and Juan Marichal serve as just a few examples. The Los Angeles Police Department often stopped in for food, usually comped by Doña Natalia who recognized that their presence offered a level of security. She also understood the need to reach out to “cultural brokers” beyond her usual orbit.[7]

This benefitted patrons and staff alike. Much of the Nayarit’s employees hailed from Latin American countries. They were often in their 20s and 30s, had recently immigrated, and spoke Spanish. However, the scene at the restaurant encompassed what historian Anthony Macías calls Los Angeles’s mid-20th century “multicultural urban civilization.” “While on the job, the waiters, waitresses, and hostesses at the Nayarit came in contact with customers from all walks of life, ordinary people and the rich and famous,” observes Molina. The restaurant’s cosmopolitanism enabled the Nayarit’s employees to “feel more a sense of comfort in and ownership of Los Angeles.”[8]

Many former Nayarit employees went on to found other restaurants and establishments. With them they carried and spread the values of the Nayarit. “Doña Natalia had encouraged her family, friends, and employees to venture out across Los Angeles and claim the city as their own.”[9] Places like The Conquistador, Barragan’s, and La Villa Taxco serve as just three examples, each fostering connections, business, personal, and political, that otherwise would not have been possible, which in itself encapsulates the thrust of Echo Park’s history from the 1920s into the 1970s.

From the 1970s until the early 2000s like many L.A. neighborhoods, parts of the community struggled with poverty and crime. Allison Anders’s 1993 film, Mi Vida Loca, a coming-of-age story focusing on a group of cholas navigating various aspects of their lives, became a sort of shorthand for describing the community. Whether it depicted all of Echo Park fairly remains a debatable point, but the film remained a point of reference for decades. When discussing the neighborhood’s gentrification in 2013, writer Colin Marshall remarked sardonically, “Maybe Anders shot scenes of Mousie and Sad Girl ordering craft beer and kale salads and left them on the cutting room floor, but I doubt it.”

Molina, attending the University of California Los Angeles around the same time as Mi Vida Loca’s release, remembered her classmates “dismissing my neighborhood as a ‘bad part of town.’” They lacked Molina notes, any sense of the community’s history. [10]

Gentrification in the early 2000s followed. “Hipsters have replaced home-boys, high-end coffee shops have pushed out mercaditos – and some of the pioneering new businesses have now been priced out themselves.” Once seen as a neighborhood in decline because of its diversity, that same trait now marks it for urban renewal; diversity as “authenticity.” Beyond its deleterious impact on long term residents and businesses, Molina objects to gentrification’s general tendency to treat communities like Echo Park as if they had no history, “as though nothing much happened before the arrival of wealthier newcomers.”[11]

The Nayarit obviously disputes such historical notions; Echo Park very much has a history before gentrification, one shaped by folks like Molina’s grandmother. Doña Natalia died in 1969. Molina’s mother sold the restaurant to Cuban entrepreneurs in the 1970s, who maintained the name until being bought out in 2001. The new owners transformed the space into a music venue, but its legacy, through its contributions to Echo Park directly and Los Angeles more broadly, continue to resonate and demonstrate that in the sprawling Los Angeles metropolis, countless stories and histories intersect on a daily basis.

As for the Echo Park Lake? The urban anchor that in some ways led to the Nayarit by providing a planet around which development could orbit underwent renovation during the 2010s. “The once muddy, sludgy water that filled the man-made lake is now sparkling and clear, the lily pads are bright green, the new playground sleek and safe,” Hadley Meares noted in a 2013 piece. “The park’s rebirth is one of L.A.’s great public works success stories of the new century.” According to Meares, despite the area’s gentrification, the park’s users remained diverse. “Latino children play on the playground while teenagers in all black huddle together under the trees. Twenty-somethings with beards and tattoos picnic on the lawn, and older couples stroll along the lake’s perimeter.” Even amidst economic change, the Nayarit’s ethos are echoed by the lake that helped create the community.

As we launch our theme month on Los Angeles, our contributors discuss various aspects of Los Angeles’ dichotomous history of sunshine and noir. Aaron Stagoff-Belfort traces the legacy of Darryl Gates and the LAPD, Emi Higashiyama explores Japantown’s survival and adaptation in the face of urban renewal, Ryan Reft discusses the archive of journalist, photographer, editor, professor, and activist Raul Ruiz and its connection to the Chicano movement of the 1970s, Charlotte Lieb delves into how Los Angeles’ famed highways contributed to its recent wildfire struggles, and Kimberly Soriano engages the history of MacArthur Park, its current uses, and its promise as a means to support harm reduction for the city’s unhoused.

Featured image (at top): Echo Park Lake with lotus flowers, palm trees, and the Los Angeles skyline in the background, Alaiben, photographer, July 12, 2019, courtesy of Wikipedia.

[1] Natalia Molina, A Place at the Nayarit: How a Mexican Restaurant Nourished a Community. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2022: 47.

[2] Molina, A Place at the Nayarit, 26-28.

[3] Molina, A Place at the Nayarit, 48.

[4] Molina, A Place at the Nayarit, 44-45.

[5] Molina, A Place at the Nayarit, 67.

[6] Molina, A Place at the Nayarit, 153.

[7] Molina, A Place at the Nayarit, 89-91.

[8] Molina, A Place at the Nayarit, 134.

[9] Molina, A Place at the Nayarit, 160.

[10] Molina, A Place at the Nayarit, 6-7.

[11] Molina, A Place at the Nayarit, 6-7.