Editor’s note: This is the sixth post in our theme for April 2025, The City Aquatic. For additional entries in the series, see here.

By Qingyun Lin

There is no spectacle in the world more wonderful to a stranger’s eyes than the river population of the Celestial Empire.[1]

—Osmond Tiffany (1823-1895)

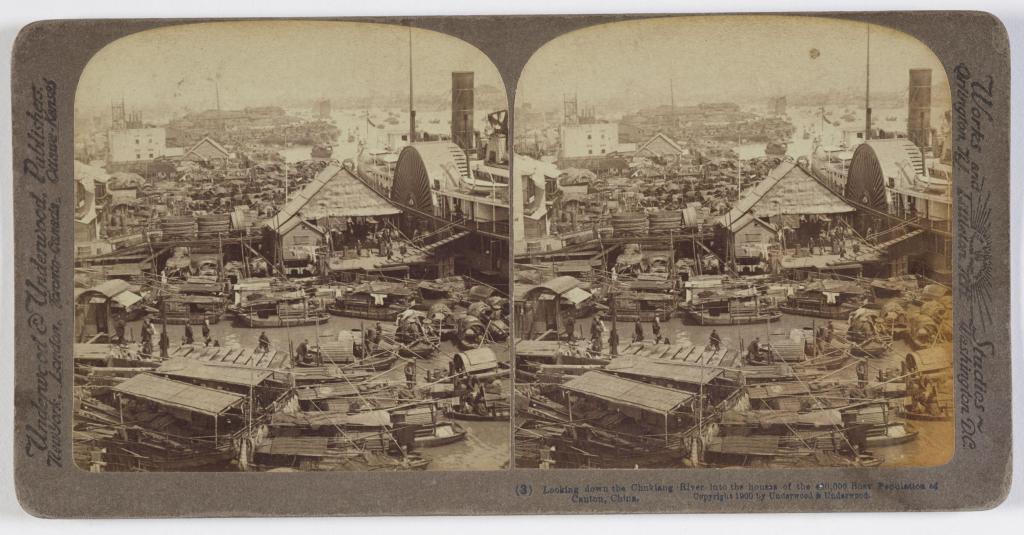

In May 1844, Osmond Tiffany—a young man from a prominent Baltimore merchant family—set sail for China aboard the barque Pioneer from the east coast of the United States. After a long voyage that took him around Cape Horn, through the Java Sea, and into the Lingding Sea—the shallow waters between Hong Kong and Macau—he finally arrived in Canton, his ultimate destination. Upon arrival, Tiffany was immediately struck by a spectacle unlike any he had encountered on his long journey—miles of boats densely covering the river in Canton, which he likened to “forty thousand wild swans closely packed together floating on some wide pond.”[2]

In the 19th century, the Canton River was a vibrant and bustling floating world of commerce and daily life with “incessant movement, the subdued noises, the life and gaiety of the river.”[3] Along the banks, large passenger boats frequently docked or set sail. Some of them were mandarin boats, lavishly decorated, with colorful flags bearing the names of their home districts and the titles of the officials on board. Gliding across the river were varnished canal and inland river boats, featuring tall masts on both sides of their midsections, used for hoisting large square sails. Near the shore, rows of ornately decorated flower boats lined up so closely that they formed what seemed like floating streets.[4] Even more striking, a vast array of small boats housed traders, craftsmen, carpenters, shoemakers, tailors, vendors, fortune-tellers, quack doctors, barbers, and even shampoo specialists—nine-tenths of these boats served as residences for entire families.[5]

Such floating populations—often labeled in 19th-century English-language travel accounts as “boat-people,” were typically portrayed as living a seemingly perpetual nature of life on water, before the term became more commonly associated with refugees fleeing Vietnam by boat and ship after the end of Vietnam War in 1975. In his travelogue, Tiffany estimated that Canton alone housed over forty thousand floating families,[6] remarking, “unlike almost all countries, where the population is confined for the most part to the shore…in China there are millions who, from the hour of birth to that of their death, have their only homes upon its waters.”[7]

Similarly, British writer Julia Cox (Mrs. John Henry Gray), who lived in Canton from 1878 to 1879, described how generations of boat people lived their entire life cycles on the water.[8] Decades later, in 1927, Robert F. Fitch (1873-1954), president of Hangchow Christian College, employed a similar language in National Geographic, portraying Guangzhou’s floating city as a place where people were “born and reared, marry, bring up families, and finally breathe their last, afloat.”[9]

These accounts seem to suggest a perpetual condition of life entirely severed from the land, yet this portrayal simplifies a far more complex reality. Rather, Canton’s floating world was never an isolated, self-contained “city within a city.” It was deeply intertwined with regional and global trade networks, continually shaped by shifting power dynamics. Its image and function evolved over time, molded by the forces of international commerce, nation-building efforts, and local economic transformations.

The City Afloat and the Thirteen Factories (1757-1842)

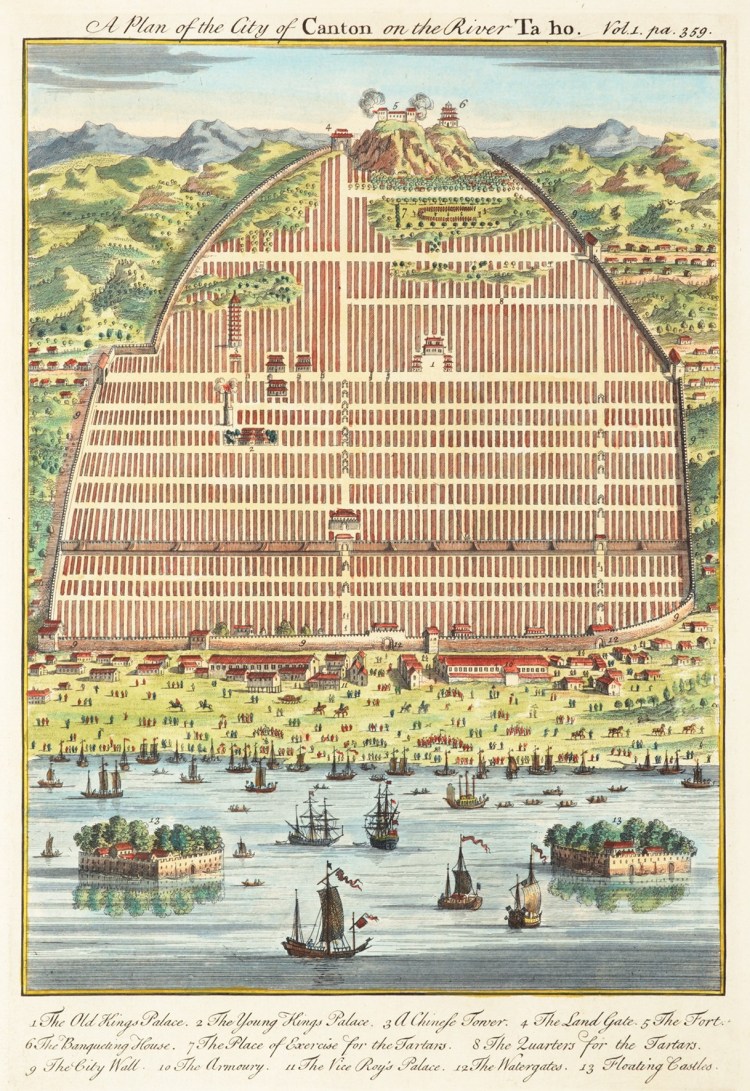

The entanglement between floating communities and the wider trade networks was especially visible during the Canton System era (1757–1842)—a time when the Qing Emperor Qianlong designated Canton (the historical romanized name of Guangzhou) as the only port officially open to foreign merchants from the sea.

Unlike Qing China’s trade with neighboring states—such as Joseon Korea, Tokugawa Japan, the Russian Empire and Southeast Asian empires—which operated through overland routes, separate treaties, tributary systems, or extensive informal trade networks led by Chinese diasporas, Western maritime trade was concentrated in Guangzhou.

The selection of Guangzhou as the sole port was strategic. As a major port on the maritime Silk Road close to the maritime trade networks of Southeast Asia, Guangzhou was an important gateway for overseas commerce. At the same time, its role as an inland port situated at the junction where the Lingding Sea flows into the Canton River and the Chinese mainland also made it an ideal site where the Qing empire could exert greater oversight and control.[10]

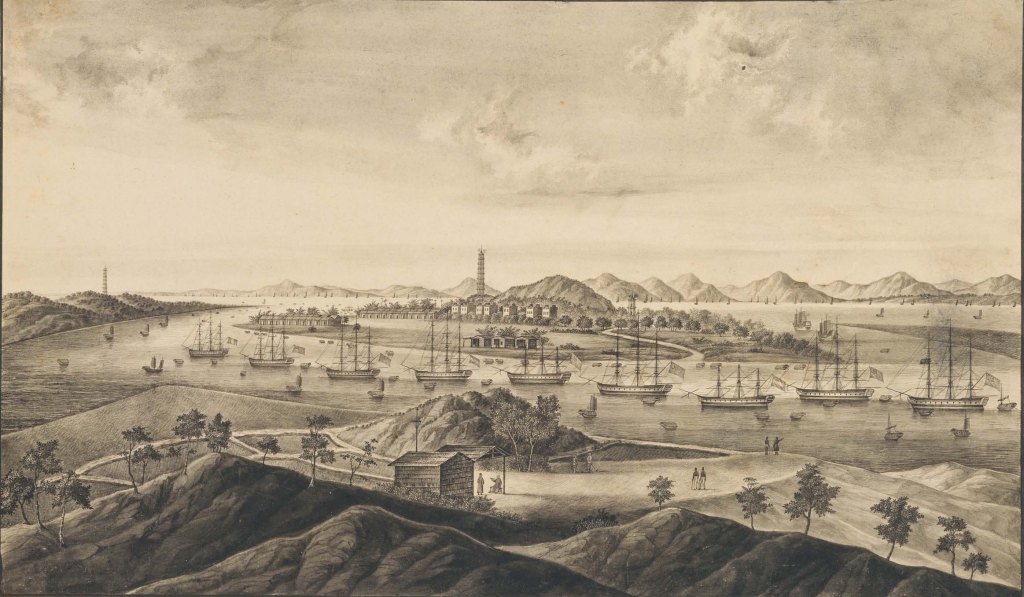

China had a set of rules to regulate foreign trade in Guangzhou. During this period, foreign merchants and officials were strictly forbidden from entering Guangzhou’s walled city. Instead, they were confined to a designated trading zone known as the Thirteen Factories, a narrow strip of land between the city walls and the Canton River, stretching about 800–1000 feet.[11] Western merchants resided in low and long buildings called “hongs (factories),” which functioned as warehouses, living quarters, and offices. Large Western merchant ships were prohibited from sailing directly to the inner river of Guangzhou before the 1840s, and instead had to anchor at Whampoa (Huangpu), a deep-water anchorage twelve miles west of the city. Most common sailors and even their captains remained aboard the ships in Whampoa for their entire stay, venturing to Guangzhou only occasionally.[12] In addition, the provision of everyday food, water, naval stores, labor, and logistics to the merchants, crews, and captains of every merchant ship and factory was handled through officially licensed compradors, a system allowing the Qing authorities to control and constrain their access to local resources.[13]

The normal running of the Canton System relied heavily on the floating city across Guangzhou and Whampoa. The compradors could almost get everything the factories and ships needed from the floating city, and many of them lived aboard small boats with their families as well.[14]

Large trading vessels consumed enormous quantities of provisions daily, and the floating communities filled this need by supplying fresh fish, duck eggs, and other aquatic products directly sourced from the river. They also transported and supplied beef, mutton, vegetables, fruits, and essential ship materials such as wood, rope, and fuel—all critical for the maintenance and operation of the merchant fleets. When necessary, the floating city offered lodging for locally hired laborers who had nowhere to sleep on merchant ships.[15] Besides, the transportation of cargos from factories to Western merchant ships anchored at Whampoa also relied on chop boats, typically operated by entire families—parents, children, and sometimes grandparents.[16]Beyond the comprador system, boat people also provided daily laundry services for merchant ships.[17] Whampoa’s floating brothels also catered to the entertainment and recreational needs of the foreign trading community.[18]

As historian Paul A. Van Dyke has argued, both the informal supplies of commodities and the provision of recreation and companionship in the floating brothels helped mitigate discontent among foreign merchants. These services reduced tensions between foreign merchants and the monopolistic Qing trading system, informally ensured the continuity of shaky trading system.[19]

Shifting Gazes on the Floating City and the Changing Representations (1842-1949)

The Canton system ended after China’s defeat in the First Opium War (1839-1842), a conflict primarily between the British Empire and the Qing Empire. The war concluded with the Treaty of Nanjing, which forced the Qing government to cede Hong Kong Island, lower tariffs, legalize opium trade, and open additional treaty ports for foreign merchants. With the rise of new treaty ports such as Shanghai, Xiamen, and Fuzhou, Guangzhou’s economic dominance began to decline.

With the changing balance of power between China and the West, the relationship between Westerners and the city afloat also evolved. After the 1840s, Western vessels no longer required specialized river pilots to navigate from Macau to Whampoa; instead, they could sail directly to the new port at Shameen (Shamian), a concession built in 1856 to replace the Thirteen Factories after the latter was completely destroyed by fire. Foreign merchants were no longer confined to the riverfront enclave; they could now enter the walled city, develop river excursions as a regular part of life in the factories, [20] and lodge in floating hotels.[21]

As foreigners ventured deeper into Guangzhou, they developed personal and emotional bonds with the floating population.[22] A surgeon accompanying the French mission (1844-1846), Melchior Honoré Yvan, described this densely populated “floating-town” of 320,000 residents as “a microcosm” of the great population centers.[23] He drew a comparison between the floating quarters and major Western metropolises such as London and Paris,[24] and portrayed the boat communities on the Canton River as the “gentlest and most obliging” Chinese.[25]

This positive depiction, however, gradually faded in later travel accounts, giving way to a mixture of pity and disdain.[26] The construction of Shameen, the English-French concession, isolated Westerners in a carefully curated colonial enclave from the rest of Guangzhou. Missionary John Macgowan (1835-1922) complained about the congestion of small boats in the narrow creek between Shamian and the city, lamenting the noise and “offensive odours which seem to form part of Chinese national life.” He described the boat people as “turbulent mobs” and “people who have never yet learned the first lesson in regard to sanitary laws.”[27] In one early 20th century newspaper, A.E. Johnson bluntly referred to the floating city as a “slum,” claiming that the misery of its inhabitants was “even more appalling than slums in the U.K.”—“picturesque” but “pestilent.”[28] Travel writer Martha Noyes Williams also noted that those unfamiliar with the East might perceive boat populations as “half-civilized.”[29]

Scholars in English Language and Literature, Tingcong Lin and Ping Su, argue that these shifting descriptions were not merely incidental. As foreign access to mainland Guangzhou increased, direct interactions with the floating population diminished, and Western narratives increasingly cast these floating communities as disorderly, unsanitary, and primitive. This rhetorical shift was a reflection of changing sociospatial relations between Westerners and Chinese. For Westerners, it was a way to define themselves—one that reinforced Western claims to cultural superiority by portraying the spaces they had more control as more civilized. [30] Such narratives served to legitimize and naturalize the growing Western presence in China, positioning foreign-controlled enclaves as beacons of modernity in contrast to the supposed disorder of local spaces.

This transformation in the image of the floating population was not confined to Western accounts. In Chinese intellectual and political circles, the late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a similar redefinition of the boat people’s identity. As Western colonial incursions intensified, Chinese political leaders and scholars sought to reconstruct national identity in the context of modern nation-state formation.[31]

Historically, the people living afloat on Canton River were derogatorily referred to as Dan, Dan-jia, or Dan-min in Mandarin or as Tanka in Cantonese, in Chinese imperial texts. The term Dan first appeared in Chinese texts in the fourth century, originally referring to a group of non-Han people (those positioned outside the dominant Han ethno-cultural identity of Chinese) living on land in the middle reaches of the Yangtze River. Over time, this label expanded to encompass a wide range of groups that Han literati perceived as uncivilized tribes in central China. It was by the 10th century that the name Dan started to be specifically applied to boat-dwelling communities in southern coastal areas.[32]

In late imperial literati writings (particularly during the Ming and Qing dynasties, 1368-1911 CE), the origins of the Dan were mythologized, linking them to marine creatures such as fish, dragons, otters, clams, and shrimps.[33] Their physical traits were also animalized, accompanied by stigmatizations that described them as unintelligent, immoral, violent, and even, inherently predisposed to killing. For instance, in Guangdong Tongzhi (The Chronicles of Guangdong Province) written by the Ming official Guo Fei (1529–1605), Dan were described as having six toes on each foot, wearing no shoes, and lacking etiquette, literacy, or even awareness of their own age.[34]

The late imperial literati’s pejorative concepts of Dan, later combined with the introduction of racial theories and social Darwinian evolutionary ideas from the West and Japan, informed late 19th and early 20th century intellectual works that studied Dan as a minority nationality. [35]

Starting in the 1920s, a group of Chinese historians, sociologists, linguists and anthropologists, such as Lo Hsiang-lin (1906-1978), Chen Xujing (1903-1967),[36] Wu Ruilin(1904-1971),[37] and Ho Ke-en,[38] began shifting the traditional focus of historiography from political elites to the lives of lower-class and marginalized communities. They conducted in-depth surveys, ethnographies and anthropometric studies on the boat people across the waterways of South Coastal China. These efforts offered an unprecedented wealth of information on the origin, demographics, occupations, customs, religious beliefs, and language of boat people.

Paradoxically, as historian Gary Chi-hung Luk observes, even though scholars acknowledged that boat people had been largely assimilated into Han—the identity with which these intellectuals themselves aligned—they were still understood as distinct ethnic group. This concept of a permanent non-Han ethnicity reflects a convergence of evolving trends in Chinese ethnohistory and anthropology with rising nationalist and patriotic believes. In the face of foreign imperialist threats from the end of the 20th century through the 1940s, Han intellectuals advocated for the transformation of China into a modern nation-state and the formation of a new national identity. In this context, the mobilization of non-Han groups in defense of the nation became ideologically and politically significant.[39]

The transformation of Western and Chinese perceptions of the boat-people between 1842 and 1949 was deeply intertwined with shifting geopolitical power relations and evolving notions of modernity, race, and national identity. These changing representations reveal less about the boat-people themselves than about the anxieties and aspirations of those who wrote about them—whether Western observers reinforcing colonial hierarchies or Chinese intellectuals reshaping national identity in an era of imperialist encroachment.

Mobility and Fluid Identity

The understanding that Dan people were, at least historically, an ethnic minority became a central premise in many mid-20th-century anthropological and sociological studies, and continues to inform public discourse and policy today. However, in recent years, scholars have increasingly challenged this racial narrative, giving the fact that, Dan people’s identities and livelihoods have never been rigidly fixed.

Works of early Chinese sociologists, such as Wu Ruiling, although holding a persistent view of boat people as a distinct ethnic group, demonstrate that some boat people had moved ashore spontaneously.[40] Social anthropologist Barbara E. Ward and historian Hiroaki Kani, in their studies of Hong Kong boat communities in the 1950s-60s, also demonstrate that boat people were not a fixed social group but a fluid population that maintained tight bonds in economy, technology, religious belief, administration, lineage, or property ownership with land people, and migrated between land and water.[41]

Over the centuries, many boat people transitioned to farming, and many farmers took to life on the water. As anthropologist Eugene Newton Anderson argues, the floating community can be understood as a dynamic entity formed by continuous departures and arrivals of people, whose water-bound life stem from their adaptations to all kinds of resources in this region.[42]

Historical records as well as anthropological studies confirm this mobility as persistent throughout history. As early as 1561, Records of Guangdong Province noted that some Dan had begun learning to read, participated in imperial examinations, and registered as commoners as land people.[43] Anthropologists Helen F. Siu and Liu Zhiwei’s research also shows that the large-scale reclamation of river marshes in the Pearl River Delta during the Ming and Qing dynasties allowed many former boat people to accumulate wealth through commercial ventures and move ashore.

At the same time, for those on the economic and social margins, extreme poverty in Qing and Ming dynasties’ highly stratified economy often pushed them toward activities that operated outside state control, including piracy—an alternative livelihood that could be interwoven with fishing. As historian Robert J. Antony argues in Pirates of the South China Coast, the late 18th and early 19th centuries saw an explosion of pirate activity in the South China Sea, with many coming from the floating population. These boat people, already skilled in navigating the treacherous waters and evading imperial oversight, were well-positioned to participate in piracy, which often provided more economic stability than legal maritime trades.[44]

Furthermore, the Dan label, as a stigmatized identity, may be deliberately discarded or strategically adopted to reinforce existing spatial orders. As Emperor Yongzheng’s 1729 edict granting land rights to the Dan population was rarely enforced locally, Dan continued to face entrenched discrimination. To secure legitimate residency on the land, they compiled genealogies and built ancestral halls to obscure their origins as Dan.[45] The locally powerful that controlled vast areas of land, in contrast, often excluded latecomers and disenfranchised competitors by reinforcing their elite status through rituals, ancestral worship, and employment of the stigmatizing discourses to differentiate themselves from others. [46]

The complexity of the label “Dan” has undermined attempts to study the Dan as a fixed ethnic group, since people who had moved ashore may still be derogatorily called Dan while land people may also seek living on water. The way boat people perceived themselves often differed significantly from how outsiders categorized them.[47] The study of Dan as a specific group of people cannot recall a distinct “remnant” of a historical Dan population, as historical anthropologists He Xi and David Faure warn, but rather reflects “the living tradition of the application of a derogatory term onto a selection of people.”[48]

Ultimately, the label Dan emerged and persisted from a complex historical process shaped by local and regional struggles over resources and power. Also, the story of Canton (Guangzhou)’s floating city is not one of isolation, but of constant adaptation and negotiation. The evolving representations of both Dan and the floating city were deeply intertwined with the rise and decline of the regional and global trade, the shifting geopolitical power relations and evolving notions of modernity, race, and national identity. They were not the other side of Guangzhou, but integral part of it, as historian Ye Xian’en notes:

…there was no sharp divide between living on land and living on water; there was, rather, a continuum…[49]

Qingyun Lin is a PhD candidate in Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the Daniels Faculty. Her research explores littoral urbanization and its entanglements with both formal state planning and architectural design, and informal spatial practices in post-1950s China. Focusing on fishers and seafaring communities—a historically marginalized and mobile population in South China and Hong Kong—she studies how they negotiated with, or sustained themselves at the margins of intensified territorial governance and the commodification of littoral space. Through oral histories, archival research, and counter-mapping, she traces how these communities adapted to degraded ecologies and shifting spatial orders by drawing on local knowledge, improvisational strategies, and more-than-human collaborations.

Featured image (at top): A Plan of the City of Canton on the River Ta Ho. (Emanuel Bowen, 1744, Wikimedia Commons

[1] Tiffany, The Canton Chinese, 22.

[2] Tiffany, 25.

[3] Hunter, The “Fan Kwae” at Canton before Treaty Days, 1825-1844, 13.

[4] Hunter, Bits of Old China, 17–19.

[5] Hunter, 18.

[6] Tiffany, The Canton Chinese, 25.

[7] Tiffany, 41.

[8] Gray, Fourteen Months in Canton, 247.

[9] Fitch, “Life Afloat in China: Tens of Thousands of Chinese in Congested Ports Spend Their Entire Existence on Boats,” 665.

[10] Van Dyke, “Forging the Canton System,” 9.

[11] Farris, Enclave to Urbanity: Canton, Foreigners, and Architecture from the Late Eighteenth to the Early Twentieth Centuries, 21.

[12] Farris, 65.

[13] Van Dyke, “Compradors and the Provisions Trade,” 51–76.

[14] Van Dyke, 56.

[15] Van Dyke, 56–62.

[16] Tiffany, The Canton Chinese, 123.

[17] Van Dyke and Mok, Images of the Canton Factories, 1760–1822: Reading History in Art, xvi.

[18] Van Dyke, “Floating Brothels and the Canton Flower Boats 1750–1930.”

[19] Van Dyke, The Canton Trade: Life and Enterprise on the China Coast, 1700-1845; Van Dyke.

[20] Farris, Enclave to Urbanity: Canton, Foreigners, and Architecture from the Late Eighteenth to the Early Twentieth Centuries, 69.

[21] Johnson, “The Floating Slums of China”; Gray, Fourteen Months in Canton, 154.

[22] Lin and Su, “The Myth of the Others.”

[23] Yvan, Inside Canton, 156.

[24] Yvan, 131.

[25] Yvan, 150.

[26] Lin and Su, “The Myth of the Others,” 5.

[27] Macgowan, Pictures of Southern China, 296.

[28] Johnson, “The Floating Slums of China,” 30.

[29] Williams, A Year in China, 157.

[30] Lin and Su, “The Myth of the Others,” 15.

[31] Luk, “The Making of a Littoral Minzu,” 6.

[32] Ho, “A Study of the Boat People.”

[33] Luk, “The Making of a Littoral Minzu,” 4.

[34] Siu and Zhiwei, “Lineage, Market, Pirate, and Dan: Ethnicity in the Pearl River Delta of South China,” 287.

[35] Luk, “The Making of a Littoral Minzu,” 2.

[36] Chen, Danmin De Yanjiu [A study on the boat people].

[37] Wu, Sanshui Danmin Diaocha [Investigation on Danshui Dan People]; Lingnan Shehui Yanjiusuo, Shanan Danmin Diaocha [A study on the dan people in Shanan].

[38] Ho, “A Study of the Boat People.”

[39] Luk, “The Making of a Littoral Minzu,” 12–14.

[40] Wu, Sanshui Danmin Diaocha [Investigation on Danshui Dan People]; Lingnan Shehui Yanjiusuo, Shanan Danmin Diaocha [A study on the dan people in Shanan].

[41] Ward, A Hong Kong Fishing Village; Kani, A General Survey of the Boat People in Hong Kong; Kani, “The Boat People in Shatin, New Territories, Hong Kong-The Settlement Patterns in 1967 and 1968.”

[42] Anderson, “The Boat People of South China.”

[43] Ye, “Notes on the Territorial Connections of the Dan,” 83.

[45] Siu and Zhiwei, “Lineage, Market, Pirate, and Dan: Ethnicity in the Pearl River Delta of South China,” 290.

[46] Siu and Zhiwei, 292.

[47] Ward, “Chinese Fishermen: Studies among the Boat-People of Hong Kong,” 3.

[48] He and Faure, The Fisher Folk of Late Imperial and Modern China: An Historical Anthropology of Boat-and-Shed Living, 3.

[49] Ye, “Notes on the Territorial Connections of the Dan,” 88.