This piece is an entry in our Eighth Annual Graduate Student Blogging Contest, “Connections.”

by Emi Higashiyama

Savannah, Georgia, may not be the most obvious place to look for a decades-long battle over city planning, but recent developments over the Civic Center proved to be a contest that revived old feuds and started new ones. Considered Georgia’s fifth-largest city, and certainly a historic one, its residents are connected to each other in complex ways—many are distant relatives, multigenerational family friends, parishioners of the same church, (former) colleagues or schoolmates, and friends sharing the same hobbies.

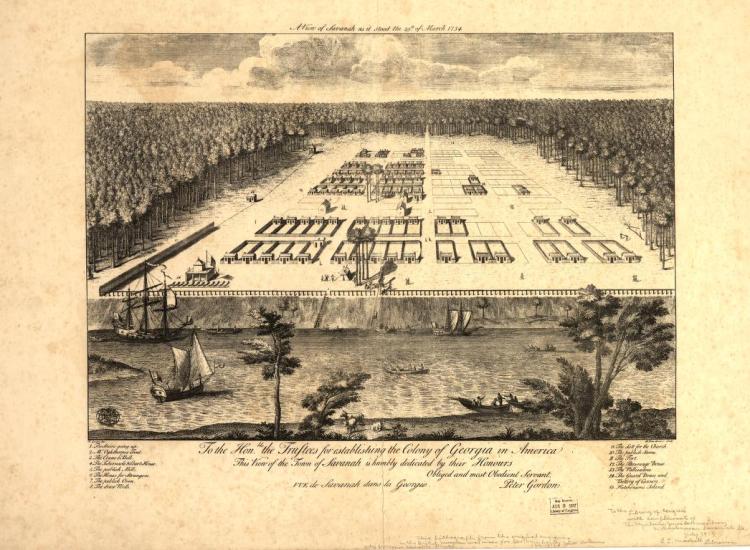

It should be no surprise, then, that when a huge topic like the Savannah Civic Center comes up, strong opinions will surface across many divided lines—and in a historic city dating back to 1733 (famous for its city plan that distinguished it from other colonial towns), there is a lot to talk about. That’s why the hottest debate (that acutely started some two decades ago)–“What do we do with the Civic Center?”–is arguably an issue that started almost three centuries ago.

When prison reformer James Oglethorpe departed his home shores in the 1730s to found Georgia and Savannah, his mission was nothing short of building an ideal society in the form of a new colony. Oglethorpe built the first four squares and surrounding neighborhoods of his planned city with the help of his friends: surveyor Noble Jones and architect William Bull. These men (whose legacies are immortalized in prominent street names) constructed an urban framework that equated architecture and community with safety and economic prosperity. The concept came to be known as the Oglethorpe Plan, its fixed grid pattern lauded as an extraordinary city planning design solution.

But as Savannah grew and its urban needs expanded, its elasticity mirrored that of the human brain rewiring itself. Although Oglethorpe’s original utopian plan was an agrarian society, Savannah’s urban development increasingly relied on its port city status for economic prosperity. Another major departure from the original social blueprint was that the original Georgia charter had four prohibitions: no Catholics, lawyers, liquor, or slaves—the allowance for slavery would eventually lead to Oglethorpe resigning as a Georgia trustee, and it was only a matter of time before the city plan itself would undergo significant changes. The direct physical connection to the past thinned with each passing decade; squares were broken up, paved over, disappeared and reappeared.[1] “What’s the big deal with preserving a square?” is a question that is often thrown around, particularly by long-time residents of the greater Savannah area who can name only a handful of the twenty-two surviving squares (and incorrectly, or misplacing them, at that).

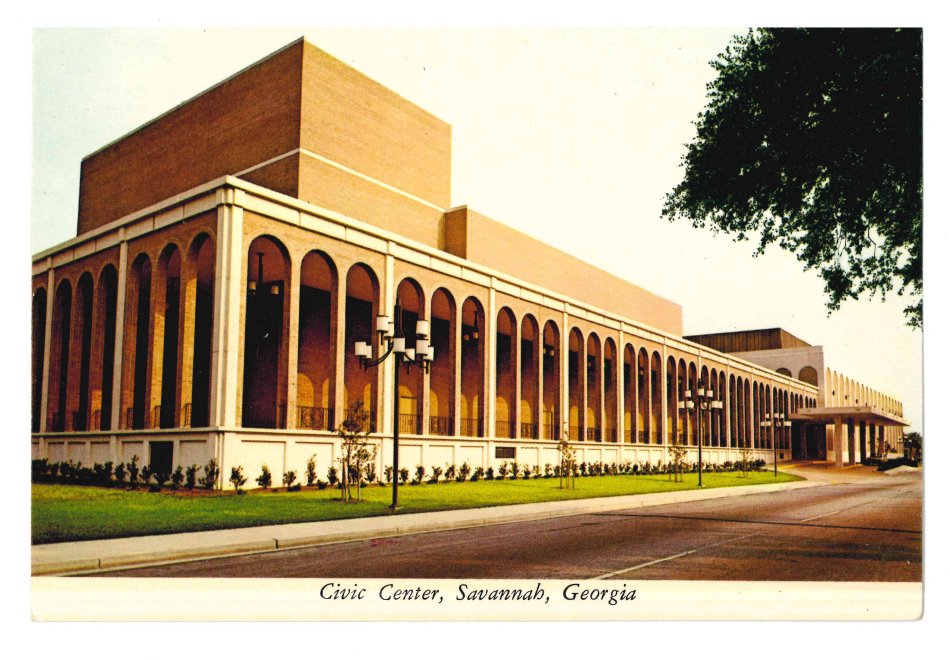

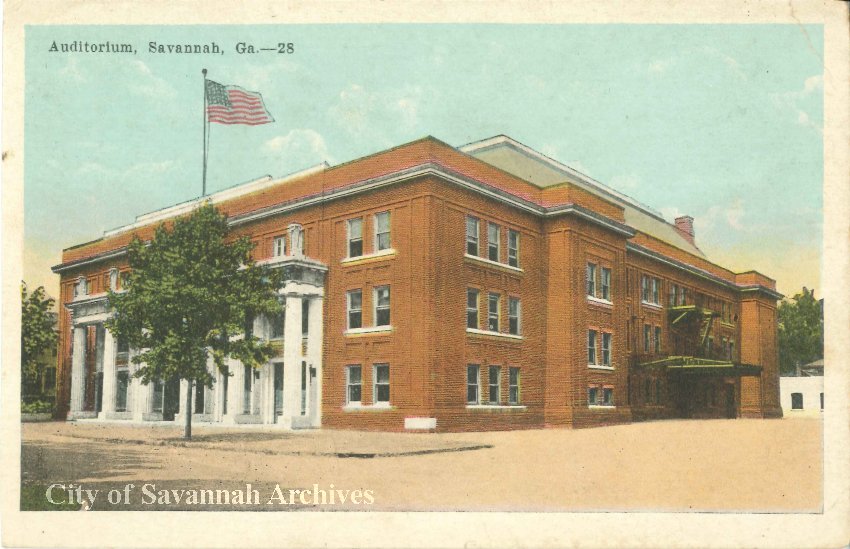

The square that is at the heart of this debate is Elbert Square, currently a mere strip of green along a wide road to the west of the Civic Center. Upon its opening in 1972, the Savannah Civic Center was meant to be an all-purpose venue where people could socially bond through concerts, sporting events, and conventions. Built on a seven-acre site where the Municipal Auditorium had previously stood, the new facility reflected the general style and goals of the 1960s: New Formalist architecture with wide, open spaces (some might say with little functional purpose) and enormous parking lots. The behemoth of a complex, smack dab in the middle of the western part of Savannah’s Historic District, was always intended as a functional memorial: named after two community giants (civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. and legendary composer/songwriter Johnny Mercer), the buildings were purpose-built to generate new community memories. Today, the site includes the 9,700-seat Martin Luther King Jr. Arena and a 2,500-seat Johnny Mercer Theatre, as well as ballrooms and multipurpose rooms for gathering. In its golden era, the Civic Center hosted musicians like Elton John, Bruce Springsteen, and Elvis Presley.

Even then, there were detractors. For some, it’s the look of the building—long-time residents see it as a blight to the architectural fabric. For others, it’s the traffic obstruction—it’s a colossus dividing the western part of downtown, disconnecting residents and businesses. It was simply par for the course in the 1970s, amidst Savannah’s urban renewal era and before the Historic District Ordinance was established as a guidepost for regulating the appearance of new development. In retrospect, the Civic Center’s most egregious flaw was in compounding the sins of the past—the destruction of both Elbert Square (and two others for US Highway 17) and the Bulloch-Habersham House, a celebrated historic mansion whose removal for the 1916 Municipal Auditorium was characterized by respected local historian John D. Duncan as “one of the worst cases of metropolitan malfeasance to be documented in an era when the preservation movement was just beginning to gain attention.”[2]

Starting in the 1990s, the topic of the Civic Center drew increased scrutiny for various nuanced reasons. Perhaps it was delayed remorse at ruining the Oglethorpe Plan—the city’s celebrated urban plan—or accumulated dissatisfaction over traffic congestion and insufficient parking, as well as the dwindling recognition of black Savannah’s economic fulcrum (the neighborhoods just west of the Civic Center). In reality, any perceived offense could have been the final straw.

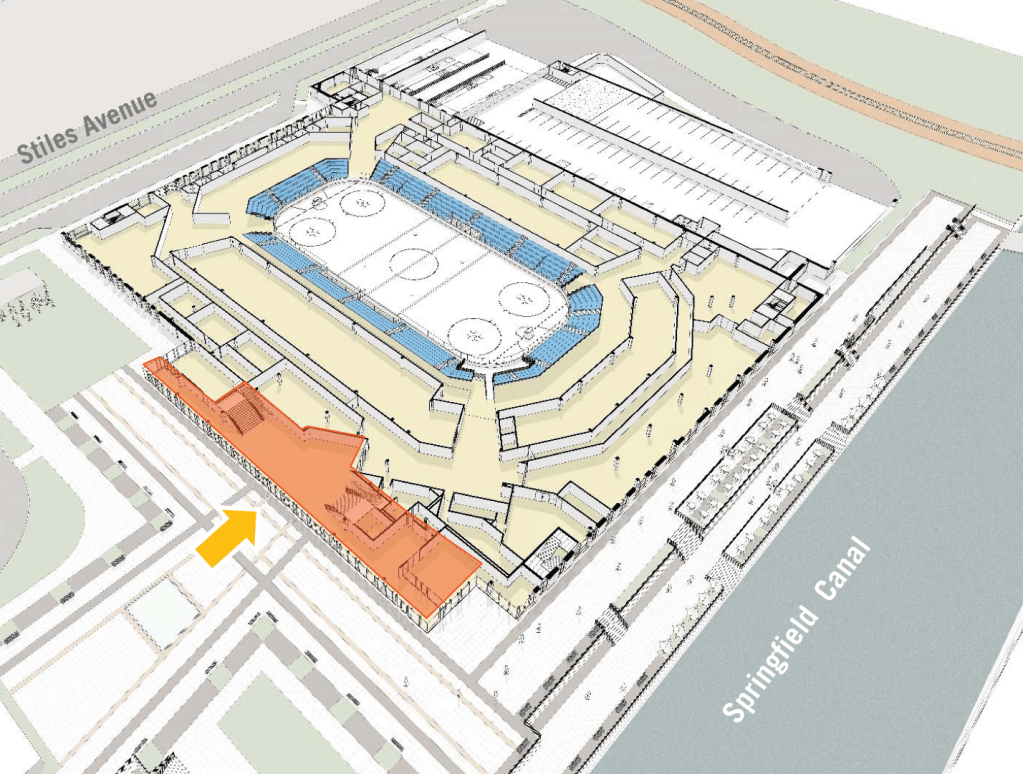

And so, in 2013, the city council designated the Canal District as the site for a new arena—and the Civic Center became the proverbial can kicked down the road. This further aggravated the long-suffering advocates in the Black community (and its members on the city council, including the city’s first Black mayor, Floyd Adams) who had lobbied for an arena to be in the predominantly Black West Savannah area.

In 2018, after the Enmarket Arena plan was unveiled for the Canal District, Marcel Williams, who grew up in Savannah and had earned his master’s degree in city planning from MIT (and whose father started the architectural history program at Savannah College of Art and Design and still runs it today), wrote a five-part series of articles questioning the transportation, financial, and environmental impacts of the project. His articles criticized the feasibility of the proposal, citing success predictors compared to the downtown arena as well as topographical challenges that were not sufficiently addressed. Those articles logged record readership in the newspaper Connect Savannah, demonstrating how one resident’s voice echoes and amplifies the sentiments of the public writ large. A few months later, Connect Savannah’s editor highlighted a call to action in the form and criticism of a city government survey that expressed a “too little, too late” sentiment when it came to involving public opinion on such important city planning projects.[3]

Fast forward to late March 2024, when the executive director of the Savannah Philharmonic emailed constituents with a video-recorded call to action to sign a petition: save the Johnny Mercer Theatre at the Civic Center. Though once a premier performance space, renovations to the lighting system ruined the acoustical integrity and made the space unusable and undesirable for music performances. This initiative was in part caused by the Philharmonic’s years-long problem of not having a suitable venue for concerts. This dearth was acutely felt for its early March choral concert, originally planned to take place at the Fine Arts Auditorium of Georgia Southern’s Armstrong Campus, which had moved to its present location nine miles south of its former 1960s site in downtown Savannah. During the first rehearsal at the performance venue, problems with HVAC and a wasp infestation caused enough of a disruption that the venue had to be changed at the last minute to the downtown Cathedral Basilica of St. John the Baptist.

It turned out to be a silver lining, because ticket sales for the Armstrong venue were dismally low—the perception most audience members had that it was “too far” meant that once the venue was changed to the Cathedral (and publicized through the Cathedral’s own concert series program), ticket sales dramatically increased and the concert was saved in more ways than one. Nonetheless, both the Armstrong and Cathedral locations were far from ideal, because stage capacity issues required all sorts of creative (and painful) logistical problem-solving.

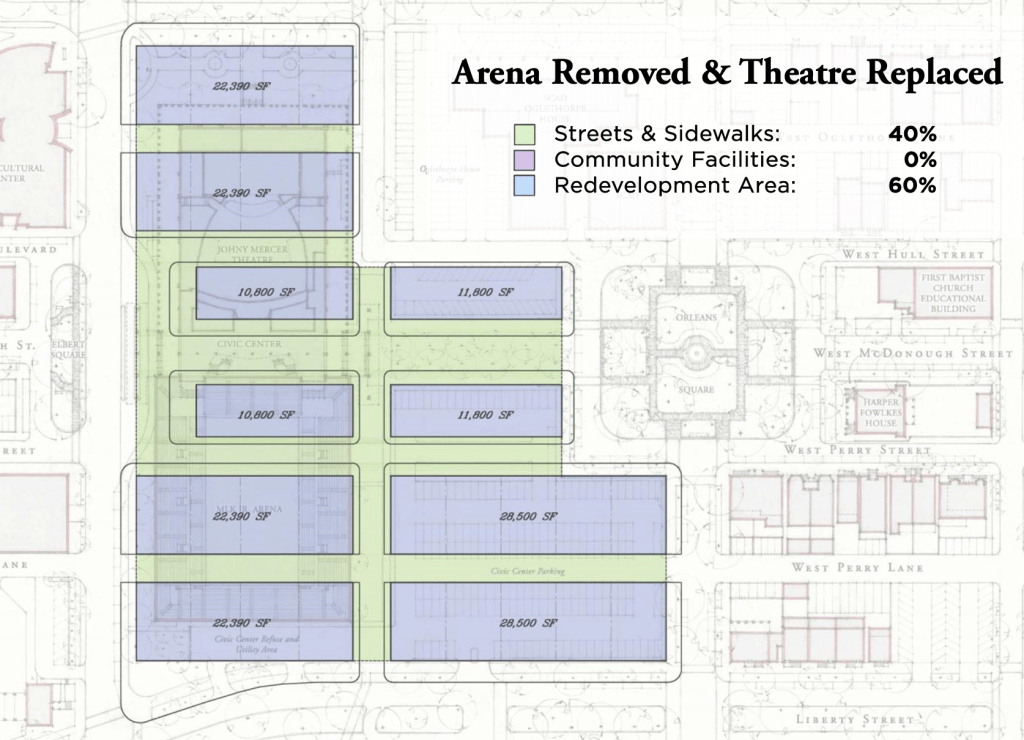

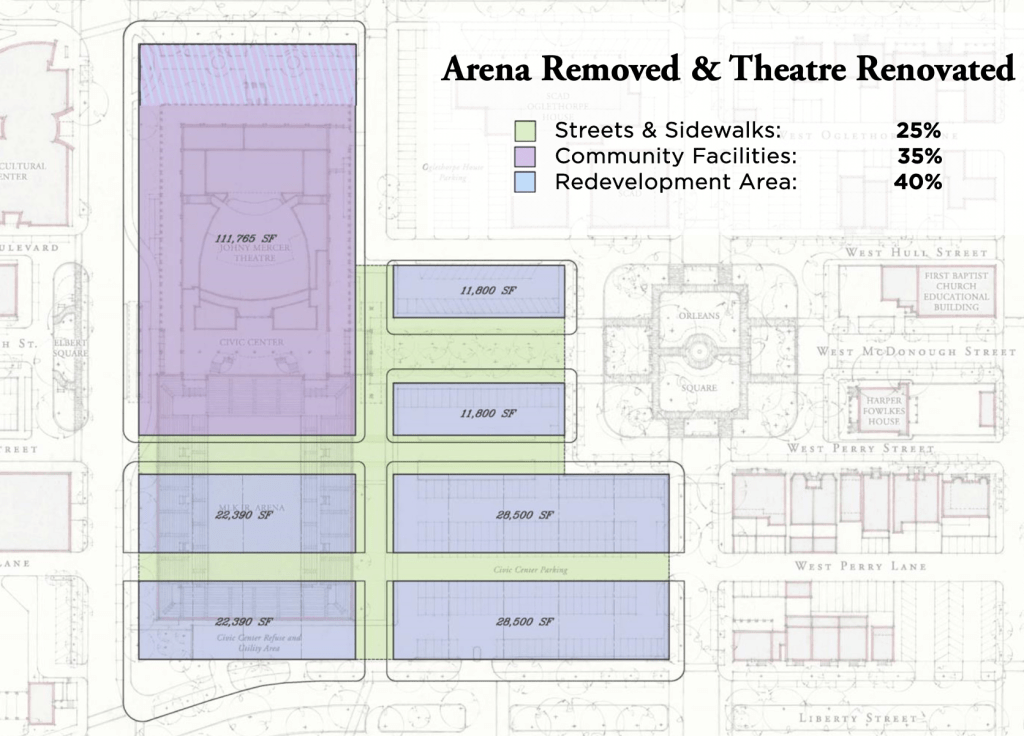

Courtesy of the City of Savannah.

For the Philharmonic’s ambitious programming in upcoming seasons, the Johnny Mercer Theatre is the likely panacea, as the city’s only truly public theater space. The city’s three other theaters are privately run, and though the Enmarket Arena has proven to be a successful large-scale event space, it was never meant to be a performing arts space with acoustical magnificence.

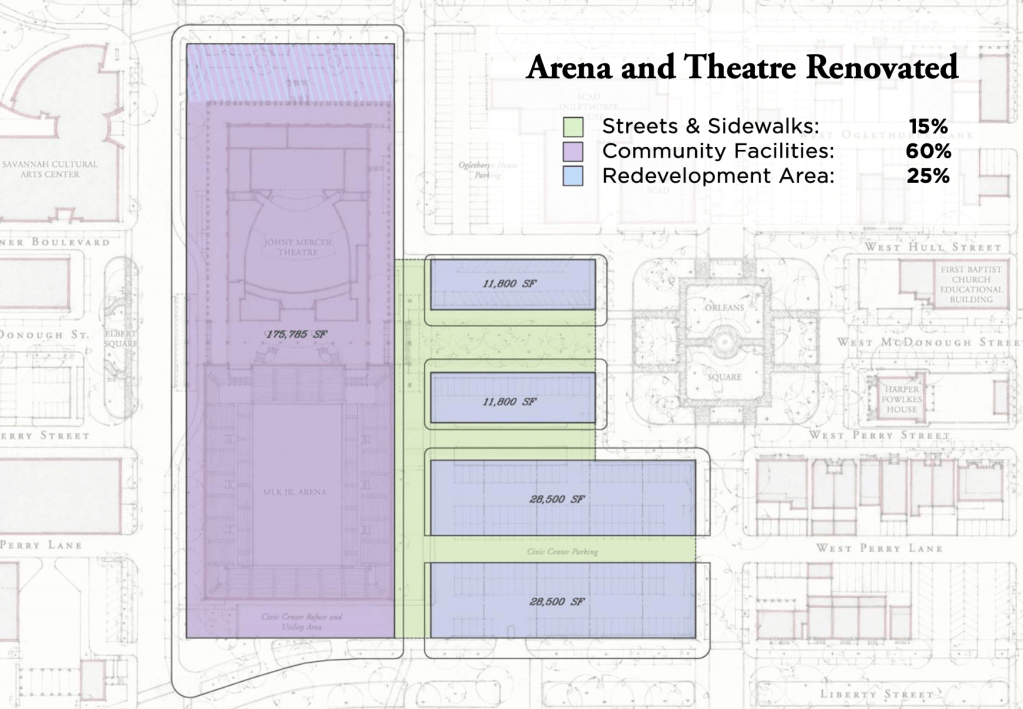

While the Philharmonic’s clarion call is solely focused on restoring the theater, there is a larger issue regarding the entirety of the Civic Center and how any reconfiguration would have lasting—perhaps dire—consequences from a once-in-a-century city planning decision. With the arena portion of the Civic Center mostly redundant, thanks to the Enmarket Arena, the city government turned to a well-known local consultant to devise a way to save the Johnny Mercer Theatre and restore some of the city’s original block plan. Christian Sottile—principal of the urban design firm Sottile & Sottile, whose personal Savannah history includes earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees from SCAD, having served as professor and dean of the School of Building Arts, as well as having his name associated with high-profile projects throughout the city—prepared three options:

Saving any part of the Civic Center (the underlying premise of the Sottile proposal), rubs the Oglethorpe Plan Coalition the wrong way. Led by Andrew Berrien Jones, pedigreed descendent of two notable old Savannah families, the coalition’s stance has always been to maintain an uninterrupted connection with the past and keep the original “Oglethorpe Plan” intact. They advocate for the complete removal of the Civic Center so that the ten-block neighborhood (several street sections and Elbert Square) can be restored in its entirety. In detailed documents found on the coalition’s website, they propose theaters be built elsewhere downtown. Their message never falters: restoration of the Oglethorpe Plan across the entire Civic Center site.

Buried in the June 2024 Civic Legacy Public Engagement Summary, Robin B. Williams (chair of the architectural history department at SCAD and the father of Marcel Williams) proposed restoring the square and retaining the theater, an option not included in the Sottile plan.[4] This uncharted option could also include restoring a street, thus strengthening the tethers of the original-and-frayed Oglethorpe Plan. This option (though perhaps a small gesture) could be seen as an active step in reversing one portion of what many have come to see as a slew of urban renewal mistakes, thus healing some social wounds and public regret. Williams, along with his colleague David Gobel, have been co-authoring a book since the early 2000s on the Savannah Plan—the names are used interchangeably, but technically a conflation best separated by historical context and architectural theory. In other words, whereas the Oglethorpe Plan may be a fixed historical artifact, the Savannah Plan is a living testament to urban elasticity and the city as an evolving organism. While a full return to the original squares-and-ward concept may be admirable, Savannah itself is no longer an agrarian society and has long abandoned the original Georgia charter by which James Oglethorpe envisioned his corner of the new world.

In late Spring 2024, town hall meetings and community workshops led up to the city council vote that would decide the fate of the Civic Center. The discussion was subject to intense racial debates that so often define civic projects. Although Savannah’s racial make-up is majority African-American, the disparity in racial equity continues to be a holdover from redlining practices of the 1930s. Perception of the favored proposal—save the theater, demolish the arena—has been described as all the focus going to the building named after Johnny Mercer, the famed son of Savannah (known for the lyrics to songs such as “Moon River,” “Blues in the Night,” and “Autumn Leaves”), while treating the Martin Luther King Jr. Arena as expendable. Parallels were being drawn that while the theater is perceived as “white space” and thus worthy of restoration, the “Black space” of the arena is an easy choice for demolition. If nothing else, then, at least the name should be preserved and honored, somehow.

On June 27, 2024, Savannah city council made its stance official: tear down the arena, renovate the theater. While many are elated at the decision, some fume with disappointment and others remain unmoored with varying degrees of ambivalence. The path to the future has been set, but the bridge is yet to be constructed. Whatever happens next, it is unavoidable that theoretical city planning will be tested with emotions and dissent. Savannah, when it comes to the Civic Center, is a Venn diagram of opposing-yet-overlapping factions that all want “what’s best” for the city. Therein, perhaps, lies the irony of the quagmire: that perhaps in all the disagreements, what’s revealed are the city’s bonds—with the past, the future, and most importantly, citizens with each other.

Emi Higashiyama is an MFA student in architectural history at the Savannah College of Art and Design. She specializes in opera houses as cultural beacons; her current research is on nineteenth-century American small town opera houses. Her other interests include music history, medieval manuscripts, and the classical/transformation eras of the Ottoman Empire.

Featured image (at top): “A view of Savannah as it stood the 29th of March 1734″ (ca. 1876), Peter Gordon, Library of Congress Geography and Map Division.

[1] Nathaniel Robert Walker, “Savannah’s Lost Squares,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 70, no. 4 (2011): 512-531.

[2] Bill Dawers, “New Book on Architect William Jay Has Contemporary Relevance,” Savannah (GA) Morning News, April 7, 2019, https://www.savannahnow.com/story/business/columns/2019/04/06/bill-dawers-new-book-on-architect-william-jay-has-contemporary-relevance/5515462007/.

[3] “Editor’s Note: What’s Important to You?” Connect Savannah, October 3, 2018, https://www.connectsavannah.com/community/editors-note-whats-important-to-you-10267262.

[4] Savannah City Government, Civic Legacy Project: Public Engagement Summary, June 2024, https://www.savannahga.gov/DocumentCenter/View/30663/.

Conflict of Interest disclosure: Emi Higashiyama is a volunteer member of the Philharmonic Orchestra Chorus and did not sign the petition to restore the Johnny Mercer Theatre. She is also a graduate student at the Savannah College of Art and Design in the architectural history department, of which professors include Robin B. Williams and David Gobel.

I’m adding this to my zotero!

LikeLike

I’ve lived in Savannah all these decades and didn’t know about most of this! Goodness, you wrote this well.

LikeLike