Editor’s note: This month we are featuring work by historians that extend Beyond the Urban. This is our first post in the series.

by Vincent Femia

It is an unimaginatively standardized background, a sluggishness of speech and manners, a rigid ruling of the spirit by the desire to be respectable. It is contentment…the contentment of the quiet dead, who are scornful of the living for their restless walking. It is negation canonized as the one positive virtue. It is the prohibition of happiness. It is slavery self-sought and self-defended. It is dullness made God.

A savorless people, gulping tasteless food, and sitting afterward, coatless and thoughtless, in rocking-chairs prickly with inane decorations, listening to mechanical music, saying mechanical things about the excellence of Ford automobiles, and viewing themselves as the greatest race in the world.

Sinclair Lewis, Main Street.

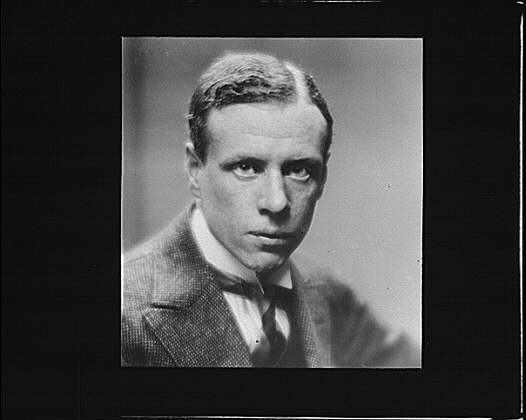

American novelist Sinclair Lewis famously despised small-town America. He grew up in Sauk Centre, Minnesota, a town of roughly 1,500 people in 1885, the year he was born. His father was a physician and a stern man who grew irritated with his son’s nomadic and eccentric life. His mother tragically passed away in 1891. At eleven, Lewis ran off, much like his characters, to become a drummer boy in the Spanish-American War. Unfortunately for Lewis, his drummer-boy dreams never came to fruition. The young man then went east, then west, and looked back only when he needed to conduct “research” on the American heartland. His field work led to Main Street (1920), which presented a troubling argument for many: the heart of America was actually its ugliest part.[1]

Before Main Street’s success, Lewis had published six other novels and many stories in magazines. He subsisted, but was only known to a few readers. Main Street changed all of that. By the time he wrote his first national bestseller, Lewis had studied at Yale, lived with writers at Carmel-by-the-Sea in California, worked as a janitor at Upton Sinclair’s Helicon Home Colony in Englewood, New Jersey, and mulled about Greenwich Village as a socialist who found Marx a bore. With his first wife, Grace Hegger, an editor at Vogue, and their son Wells, Lewis relocated to Washington, DC, which he found a pleasant compromise between the precarities of New York and the monotony of the suburbs. So much in science, politics, and even literature could be discovered in the nation’s capital, the city he would call home as he wrote Main Street, Babbitt (1922), Arrowsmith (1925), and Elmer Gantry (1927).

Main Street presented an idea Lewis had mulled over for years. In the summer of 1905, Lewis had jotted down in his journal the genesis of the “village virus”: “In company with Paul Hilsdale,—drank too much port wine. ‘The village virus’;—I shall have to write a book of how it getteth into the veins of good men & true. ‘God made the country & man made the town—but the devil made the village.’”[2] The “village virus” dulled the ambition of men and women and trapped them in the eddies of meaningless contentment. Figuratively, it neatly stitches together Lewis’s novels Main Street and Arrowsmith, the former about an audacious town booster and urban romantic, and the latter about an aspiring doctor and scientist eventually challenged with treating bubonic plague on a fictional Caribbean island.[3]

In their realism, Lewis’s novels intended not to escape American life, but face it head on. We witness, in satirical and vitriolic fashion, a man’s perception of the viruses eating away at early twentieth-century American culture. The critique is always juxtaposition. Lewis reveals what is spoiled and rotten through a yearning for an attractive alternative, glowing bright in the far-off horizon. As both an historian of science and urban historian, I became fascinated by Lewis and his novels. He is obsessed with looking forward, toward an unsettled modernity that will breathe life into the slow and provincial minds of his country men and women. In Main Street and Arrowsmith, those yearnings find expression in the town and city boosterism of Carol Kennicott and the scientific idealism of Martin Arrowsmith. Science and city intertwine as these characters restlessly move, constantly in search of pure forms of expression—science for science’s sake, or the self-actualization of immersion in the pulse and rhythm of the modern metropolis.

As clear products of their time, Lewis’s novels present themes that would be incredibly familiar to a historian of the early twentieth century—corporatization, technocratic control, the expansion of consumption, eugenics, nationalism during World War I, gender liberation, and more.[4] But how can these sources (Main Street and Arrowsmith, in particular)—read by millions of Americans in the early twentieth century—provide a glimpse into how science and city existed, together, as pillars of modern American thought? What can Lewis’s focus on the small town reveal about urban history? And did living and working in Washington, DC, matter for how he chose to write these stories?

One thing is clear. For Lewis’s characters, that shimmering horizon is both near and far. Indeed, it exists practically everywhere you look; the small town and the city cannot be separated. Lewis hated small town America not because it was so backward or antiquated, but because it was modern in the most mundane and grotesque ways possible. Main Streets were interchangeable parts, assembled on the factory lines of American consumer capitalism and filled with folks with hollowed out souls, happy to spend their evenings talking about cars, town gossip, and bastardized caricatures of far-off politics. The quaint world of the premodern town had “passed forty years ago.” Instead, “Carol’s small town thinks not in hoss-swapping but in cheap motor cars, telephones, ready-made clothes, silos, alfalfa, kodaks, phonographs, leather-upholstered Morris chairs, bridge-prizes, oil-stocks, motion-pictures, land-deals, unread sets of Mark Twain, and a chaste version of national politics.”[5] The edges had been sanded down by an abundance of things. The village virus traveled where it could along the vectors of capitalism, building Main Streets like company towns.

Lewis first came to Washington, DC, in 1910 to work as a kind of subeditor and clerk at the Volta Review, the journal connected to Alexander Graham Bell’s Volta Laboratory and Bureau for the Increase and Diffusion of Knowledge Relating to the Deaf. Lewis had earned his train ticket money from The Call of the Wild author Jack London. Still an unknown writer and recent Yale graduate, Lewis befriended London at the writer’s oasis of Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. London decided to purchase some of Lewis’s plot ideas.[6]

Main Street and Arrowsmith were still years off, but at the Volta Review, on a measly fifteen dollars a week, Lewis studied, when he could, the unpublished notes of Alexander Graham Bell’s flying experiments. He had come east, just as Carol and Martin would a decade later, and embraced a fascination with science and invention. After a sudden move to New York, Lewis spent weekends on Long Island socializing with aviation pioneers. His first published book, Hike and the Aeroplane (1914), used Alexander Graham Bell’s blueprint for a motorized tetrahedral kite as a model for the story’s aircraft.[7] While Lewis’s work became famous for its scathing critiques of small-town life, both Carol Kennicott and Martin Arrowsmith—just like Lewis—move through many parts of America, doing battle with the provincial curses of Gopher Prairie and the corporate consciousness of New York industry. Lewis lived a life on the move. He knew Sauk Center all too well, had lived as a Bohemian in Greenwich Village, and struggled to find meaning with his first wife, Gracie, in the suburb of Port Washington, New York. Lewis’s novels were unabashedly about his own life—Carol, in particular, is quite clearly both Gracie and Lewis mixed into one.

Main Street tells the story of an ambitious and hard-headed young woman named Carol Milford. Before her move to Gopher Prairie (a fictionalized Sauk Centre, Minnesota), Carol becomes interested in town and city planning in college, studies in Chicago at a library school, and works as a librarian in Saint Paul, Minnesota. She ends up marrying a doctor, Will Kennicott, and he convinces Carol to move to his home town of Gopher Prairie. There, Carol’s struggles begin as she encounters the village virus run amok. Her neighbors gaze at her with both intrigue and concern, that “sociological messiah come to save Gopher Prairie.”[8] Her frustrated feelings toward the town play out in her unsettled feelings toward her husband. At times, she is righteous and inspiring, and at others, naïve and dismissive. Carol and Will occasionally go to the city (such as Chicago or St. Paul) to enjoy its attractions as small-town urban tourists, but the two are split on the value the city has to offer.

Lewis wrote that the small town suppressed the spirits of women and young men. In the city, be it Minneapolis, New York, or Washington, DC, Carol Kennicott longed for a gender liberation that came with both professional opportunity and “cheap amusements.”[9] “It’s one of our favorite American myths that broad plains necessarily make broad minds,” she proclaims, “and high mountains make high purpose.”[10] Pushed to her limits, Carol finds she needs to shed Gopher Prairie, at least for a while, so she moves to Washington, DC, to work in the Bureau of War Risk Insurance during World War I. She imagined the capital city would be safer than New York for her young son (Gracie and Lewis chose to move to Washington in 1919 for this very same reason). The Lewis family lived at 1814 16th Street NW until June 1920, when Lewis moved into the Cosmos Club and Gracie left with their son for some time away from the city.[11] Much of the feminist rhetoric in Lewis’s novels was lost on critics, including Lewis’s ardent supporter H. L. Mencken. Carol was both enlightened and flawed, and interpretations of her traveled in both directions.[12] In Washington, Carol finally felt that she was no longer “one-half of a marriage but the whole of a human being.”[13]

Arrowsmith tells a somewhat similar story (maybe in reverse), following a young man through his professional training as a scientist and doctor as he makes his way from a small Midwestern town to a research institute in New York City. Martin is a flawed character, much more so than Carol. He consistently has affairs, gets into spats, and makes questionable choices based upon what he believes to be the values of science. Like Carol, who thought that “scientists ought to rule the world,” Martin imagined a future Department of Health where the best physicians could be made “autocratic officials.”[14] The University of Winnemac, where Martin Arrowsmith attended college, appeared much like the Main Street of Gopher Prairie, an engine of middle-class drudgery: “It is not the snobbish rich-man’s college, devoted to leisurely nonsense. It is the property of the people of the state, and what they want—or what they are told they want—is a mill to turn out men and women who will lead moral lives, play bridge, drive good cars, be enterprising in business, and occasionally mention books, though they are not expected to have time to read them. It is a Ford Motor Factory, and if its products rattle a little, they are beautifully standardized, with perfectly interchangeable parts.”[15]

In his own life, Lewis maintained science to be the real and most effective form of knowing the nature of reality. Science had an art, like poetry, Lewis portrayed in his novels, but its utility and noble realism would help put the United States on par with Europe, eroding the quackery of religious fundamentalism and other spiritual practices in America. In 1919 Lewis wrote a long piece in The Washington Post on “spiritualist vaudeville.” Like a good social scientist, Lewis spent considerable time at the Lily Dale Spiritualist Assembly in New York State “investigating seances, slate writing, spirit messages, and similar phenomena.” “Trickery, not truth, prevails at Lily Dale.”[16] At the height of the Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925, Lewis publicly ridiculed William Jennings Bryan for allowing nations to “roar with laughter” at his defense of antievolution beliefs. A year later, he continued the fight locally, attacking Maj. Gen. Amos O. Fries for seeking to fire Henry Flury from Eastern High School in Washington, DC, for teaching “modern” biology.[17]

Lewis, who was older than most of his Lost Generation comrades, including fellow Minnesotan F. Scott Fitzgerald, exudes a politics often more in line with the Progressive Era ideals he was born into.[18] His admiration of the lectures of Emma Goldman in the Village, novels of Theodore Dreiser, and the politics of Eugene Debs—a familiar American Moderns story—paired with a less proletariat vision of technocratic control and planning that would ostensibly uncurl the greedy grip of corporate capitalists.[19] Michael Augspurger has argued that Lewis’s novels of the 1920s “worried about the corrupting influence of a corporate society on the ‘pioneer’ ideals of the professional managerial class.”[20] The technocrats could easily slip into the capitalist current. For Martin Arrowsmith, this fear expressed itself in the anti-capitalist “scientific attitude,” a pursuit of truth free from industrial control.[21] Max Gottlieb, Martin’s scientific mentor, was that high priest of science, refusing to give his unfinished scientific knowledge over to the Pittsburgh company he worked for.[22]

Yet the scientific attitude was itself corrupting. Martin discovers a phage that can be used to treat a bubonic plague pandemic on a fictional Caribbean island. Despite the mounting death toll, Martin refuses to distribute the phage, as he had yet to run proper trials. A brief conversation in Main Street foreshadows Lewis’s characterization of the young scientist: “These crack specialists, the young scientific fellows, they’re so cocksure and so wrapped up in their laboratories that they miss the human element.”[23] Only after his wife Leora dies from plague does Martin have a change of heart. The world still celebrates Martin for his work, and he is even offered the directorship of the McGurk Institute in New York. But he goes off to Vermont to join Terry Wickett, a fellow chemist at the Institute, and dedicate his soul to the pursuit of science.

Lewis immersed himself in Washington’s intellectual world after his return to the city in 1919. His return also reignited his relationship with his old boss, Gilbert Grosvenor, editor of National Geographic and the Volta Review, and son-in-law of Alexander Graham Bell. In 1920, Lewis joined the Cosmos Club and found himself loitering about the clubhouse, talking to whomever was there, be it a lawyer, writer, scientist, or his old boss. Presenting Lewis to the Committee on Admissions at the Cosmos Club, Grosvenor claimed his former employee displayed “the realistic powers of Balzac, but all his writing is clean, and he has the cleverest and most facile knack of depicting persons we meet in everyday American life of any present-day writer with whom I am acquainted.”[24] Dean Acheson became a close friend and read early drafts of Main Street. Gracie and Lewis audited classes at Howard University and became fascinated with race in America, especially after the riots that erupted in American cities during the red summer of 1919.[25] Many years later, Lewis wrote Kingsblood Royal (1942), a novel about a white, middle-class man who discovers his Black ancestry and is forced to deal with the growing racism he faces from his community as the news of his ancestry spreads.

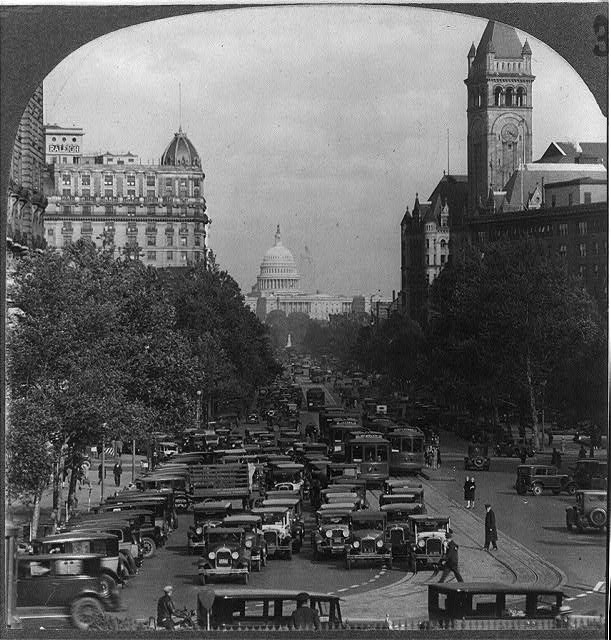

For Lewis, Washington really was that “city of conversation” Henry James had described years ago. The city hosted “people, scores of them, sitting about the flat, talking, talking, talking, not always wisely but always excitedly.”[26] Washington made sense for Lewis. Since the 1870s, scores of Midwesterners had transplanted to the capital for new postbellum opportunities. A new moneyed class from Chicago, Cincinnati, and other burgeoning Midwestern cities sought inroads in a powerful city with a relatively ill-defined class structure.[27] Young scientists from the Midwestern states (usually self-trained) also traveled to Washington for positions in the growing scientific state, not so unlike Lewis’s dreamy pursuit of artistic meaning in the streets of Greenwich Village.[28] Many of the Midwestern scientists who arrived in Washington in 1870s and 1880s remembered a “simple” life of meager government salaries, cheap food and housing, and the excitement of participating in government scientific work day in and day out.[29] But in Washington, Lewis (and Carol) found a chemical solution of both metropolis and Main Street. Carol discovered that the “office is as full of cliques and scandals as a Gopher Prairie.”[30] “Carol recognized in Washington as she had in California a transplanted and guarded Main Street.”[31]

The village virus was not geographically bound. It moved like what it was: a pathogen. Those who had ventured to the heart of the city could find, one day, the village virus welling up in them once again. Lewis located the disease of complacency in a virus, studying it under a microscope. For Carol, time and again, “she was snatched back from a dream of far countries, and found herself on Main Street.”[32] Washington was a city of government, not industry, almost pastoral compared to New York.

As she flitted up Sixteenth Street after a Kreisler recital, given late in the afternoon for the government clerks, as the lamps kindled in spheres of soft fire, as the breeze flowed into the street, fresh as prairie winds and kindlier, as she glanced up the elm alley of Massachusetts Avenue, as she was rested by the integrity of the Sottish Rite Temple, she loved the city as she loved no one save Hugh [her son]. She encountered Negro shanties turned into studios, with orange curtains and pots of mignonette; marble houses on New Hampshire Avenue, with butlers and limousines; and men who looked like fictional explorers and aviators.[33]

Sinclair Lewis, Main Street.

Washington was full of “experts from bureaus,” many of whom Lewis would meet at the Cosmos Club. A city of conversation, yes, but also a city of numbers. Instead of the artist’s salon Carol imagined, most “thought more in card-catalogues and statistics than in mass and color.”[34] Washington deflated the bloated importance of Gopher Prairie, but “always she was to perceive in Washington (as doubtless she would have perceived in New York or London) a thick streak of Main Street.”[35]

Decades of scholarship in urban history have taught us that the city is never an environment in isolation. William Cronon’s influential work on Chicago and its hinterlands is perhaps our most influential reminder.[36] In the history of science, what science is, how it is practiced, and how it is influenced has grown expansive to the point where many historians have started questioning the utility of “science” in the label “history of science” to signify what we as historians of science really do. Similarly, what the “urban” is has obvious answers, but is riddled with gray area in need of exploration.

Lewis’s novels invite us to expand that geography, but also place it under a microscope. The small town and the city are both products of circulation—goods, capital, people—that often overlap in more ways than immediately detected. I am reminded of the corporate Main Streets sprouting up in today’s DC, my home town, in the gentrifying neighborhoods of the city. The blocks of WeWorks, fast casual chains, banks, and Planet Fitnesses are the interchangeable parts, less something distinctly urban than a corporate kaleidoscope. Lewis’s novels show a wrestling with a culture and politics of transition, from a Progressive Era idealism to a more modernist disillusionment. City and science are presented as both ideal and corrupted forms—honest ways to know and live, yet rarely as honest as you would like them to be. Lewis gives his readers a picture of ostensibly separated worlds (the small town and the city, the laboratory and the field) united by the encroachment of capitalist modernity.

Maybe the connection between science and city, for Lewis, was more about escape than reality. The realism of his novels is instead an exploration of the antirealist aspirations of the author himself, and many more of his era who grappled with accelerating dynamics of change. “Always, in America, there remains from pioneer days a cheerful pariahdom of shabby young men who prowl causelessly from state to state, from gang to gang, in the power of the Wanderlust. They wear black sateen shirts, and carry bundles. They are not permanently tramps. They have home towns to which they return, to work quietly in the factory or the section-gang for a year—for a week—and as quietly to disappear again. They crowd the smoking cars at night; they sit silent on benches in filthy stations; they know all the land yet of it they know nothing, because in a hundred cities they see only the employment agencies, the all-night lunches, the blind-pigs, the scabrous lodging-houses.”[37] For Carol and Martin, success was something hard to pin down, the goal always a blur behind a nervous restlessness. For Lewis, the answer came as no answer at all. But simply writing it down was the first step.

Vincent L. Femia is a PhD candidate in the history of science at Princeton University. His work focuses on histories of science and the American city at the turn of the twentieth century. Before beginning his PhD at Princeton, Vincent completed an MPhil in the history and philosophy of science at the University of Cambridge.

Featured image (at top): “Sinclair Lewis” (1914), Arnold Genthe, photographer, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

[1] Most of the details of Sinclair Lewis’s life in this essay come from Mark Schorer, Sinclair Lewis: An American Life (New York: McGraw Hill, 1961) and Richard Lingeman, Sinclair Lewis: Rebel from Main Street (New York: Random House, 2002).

[2] As quoted in Lingeman, Sinclair Lewis, 24.

[3] For Arrowsmith, Lewis worked closely with American microbiologist and science writer Paul de Kruif. Arrowsmith became the first major American novel with a research science as its main protagonist. For Arrowsmith placed within a history of science and social history context and the importance of de Kruif in constructing the novel, see “Martin Arrowsmith: The Scientist as Hero,” in Charles E. Rosenberg, No Other Gods: On Science and American Social Thought (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976, 1997), 123-131.

[4] A list of works covering such themes would fill a book, but several works useful in situating Lewis’s novels include Nick Salvatore, Eugene V. Debs: Citizen and Socialist (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1982); John Bodnar, The Transplanted: A History of Immigrants in Urban America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985); Daniel Kevles, In the Name of Eugenics: Genetics and the Uses of Human Heredity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985); William Leach, Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of New American Culture (New York: Vintage Books, 1993); George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940 (New York: Basic Books, 1994); Jackson Lears, Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America (New York: Basic Books, 1994); Theodore M. Porter, Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1995); Daniel Rodgers, Atlantic Crossings: Social Politics in a Progressive Age (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998); Christine Stansell, American Moderns: Bohemian New York and the Creation of a New Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000); Charles Postel, The Populist Vision (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); Christopher Capozolla, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

[5] Sinclair Lewis, Main Street (New York: Signet Classics, 2008), 284.

[6] Lingeman, Sinclair Lewis, 37.

[7] Lingeman, Sinclair Lewis, 48; Schorer, Sinclair Lewis, 170; Franklin Walker, “Jack London’s Use of Sinclair Lewis Plots, Together with a Printing of Three of the Plots,” Huntington Library Quarterly 17 (1953): 59-74.

[8] Lewis, Main Street, 273.

[9] Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements: Working Women and Leisure in Turn-of-the-Century New York (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986). Peiss’s argument that “women’s embrace of style, fashion, romance, and mixed-sex fun could be a source of autonomy and pleasure as well as a cause of their continuing oppression” aligns with Lewis’s portrayal of science and city: modern liberatory forces that have tendencies of oppression given their ties to consumption and capitalist production.

[10] Lewis, Main Street, 363.

[11] The Cosmos Club was founded in 1878 to provide a more exclusive social space for scientists in the city. The club had a dual function. It acted as a social club, hosting parties and other social events, and it served as the venue for the meetings of many of the specialist scientific societies in the city. These specialist societies would also invite guest lecturers to appear at the Cosmos Club. By 1920 the Cosmos Club, still the center of scientific socialization in the city, was a mix of scientists, lawyers, politicians, writers, artists, and other intellectuals. See Wilcomb E. Washburn, The Cosmos Club of Washington: A Centennial History, 1878-1978 (Washington, DC: The Cosmos Club of Washington, 1978).

[12] Lingeman, Sinclair Lewis, 153.

[13] Lewis, Main Street, 446.

[14] Lewis, Main Street, 416 and Sinclair Lewis, Arrowsmith (New York: Signet Classics, 2008), 170.

[15] Lewis, Arrowsmith, 6-7.

[16] Sinclair Lewis, “Sinclair Lewis Strongly Assails the Spiritualists,” The Washington Post, October 12, 1919.

[17] “Evolution Case Stirs World Laughter: Sinclair Lewis, Back From Europe, Declares Bryan Has Made U.S. a Joke,” The Washington Times, June 3, 1925, and “Sinclair Lewis Flays Fries Attack on Flury,” The Washington Times, November 19, 1926. For the story of the Scopes trial, see Edward J. Larson, Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America’s Continuing Debate over Science and Religion (New York: Basic Books, 1997). Major General Amos A. Fries became heavily involved in chemical testing and warfare during World War I, heading the Chemical Warfare Service, Overseas Division. Lewis’s pacifism also likely played into his critique of Fries: “When did this man, trained in the manufacture of poison gas, become the judge of what we should teach in our public schools?”

[18] Main Street quickly became Fitzgerald’s favorite American novel after its publication in 1920. Born in 1896, Fitzgerald was a child and teenager during the height of progressivism. Born eleven years earlier, Lewis lived his young professional life through the heart of the Progressive Era, which, depending upon who you ask, ended roughly with World War I. Lingeman, Sinclair Lewis, 151.

[19] Daniel Rodgers has argued that what made Progressive social thought distinct was the presence of the languages of antimonopolism, social cohesion, and social efficiency. Moreover, he has argued that the central issue facing American society during the Progressive Era was the extent to which public goods ought to be delivered through the marketplace. Daniel T. Rodgers, “In Search of Progressivism,” Reviews in American History 10, no. 4 (1982): 113-132 and Daniel T. Rodgers, “Capitalism and Politics in the Progressive Era and in Ours,” The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 13, no. 3 (2014): 379-386. See also Michael McGerr, A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003) and Stansell, American Moderns.

[20] Michael Augsberger, “Sinclair Lewis’ Primers for the Professional Managerial Class: ‘Babbit,’ ‘Arrowsmith,’ and ‘Dodsworth’,” The Journal of the Midwest Modern Language Association 34 (2001): 75.

[21] Lewis, Arrowsmith, 427.

[22] Lewis based Max Gottlieb on German-born American biologist Jacques Loeb. Loeb became an early champion of Ernest Everett Just, biologist and professor at Howard University, and one of the first Black men to receive a doctorate in the sciences. Loeb, however, eventually turned on Just in the 1920s after Just began criticizing his work on artificial parthenogenesis. Loeb worked to deny Just an important fellowship and a possible position at the Rockefeller Institute in New York (what Lewis’s McGurk Institute was based upon). Given his interest in science, race in America, and Loeb (in particular), Lewis perhaps could have met Just in the halls of Howard University while he was auditing. See Kenneth R. Manning, Black Apollo of Science: The Life of Ernest Everett Just (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983).

[23] Lewis, Main Street, 302-303.

[24] “Facile,” in this sentence, means effortless, rather than superficial. Gilbert Grosvenor to the Committee on Admissions of the Cosmos Club, December 24, 1920, Box I: 117, Grosvenor Family Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

[25] Lingeman, Sinclair Lewis, 136-142.

[26] Lewis, Main Street, 448.

[27] Kathryn Allamong Jacob, Capital Elites: High Society in Washington, D.C., after the Civil War (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995), 140-167.

[28] W J McGee, John Wesley Powell, Lester Frank Ward, Harvey Washington Wiley, William Temple Hornaday, William Henry Holmes, and George Brown Goode were among the many new Midwestern faces in postbellum federal science, most of whom were naturalists.

[29] Entomologist Leland O. Howard reflected on this “simple” life in his 1933 autobiography. He lived in a room with his friend MacBorden for ten dollars a month and was able to eat fine meals at nearby restaurants, such as the Holy Tree Inn on 9th Street just below F, for twenty-five cents. See Leland O. Howard, Fighting the Insects: The Story of an Entomologist, Telling of the Life and Experiences of the Writer (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1933). Many of these young scientists shared rooms in what was then pejoratively referred to as the Hell’s Bottom neighborhood, north of today’s Logan Circle. Howard moved to that area in the 1880s. W J McGee, Charles Valentine Riley, and Otis T. Mason were among the others in the neighborhood.

[30] Lewis, Main Street, 445.

[31] Lewis, Main Street, 447.

[32] Lewis, Main Street, 220-221.

[33] Lewis, Main Street, 446-447.

[34] Lewis, Main Street, 448.

[35] Lewis, Main Street, 447.

[36] William Cronon, Nature’s Metropolis: Chicago and the Great West (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991).

[37] Lewis, Arrowsmith, 96.

Hmm, a history publication that scrubs dates off of their articles? Hard to take seriously.

LikeLike

Hello Simone, the dates are not scrubbed but rather can be seen when viewing the article before you click on it. For example, see here: https://themetropole.blog/category/beyond-the-urban/. April 3, 2024 for this one. Take care.

LikeLike

Thank you for your reply to my comment regarding the dates not appearing on your articles. I understand that they only disappear after one has begun reading the piece. This still seems a bit dubious. What reasoning is there for it? Removal of empowering data has been rampant across many platforms and it bodes ill, in my opinion. Thanks again.

LikeLike

We have no control over it, it’s got to do with the template selected for the blog. But you did make an incorrect assertion. Nothing has been scrubbed as illustrated.

LikeLike