By Andrew Wiese

Editor’s note: In anticipation of the Society for American City and Regional Planning History’s (SACRPH) 2024 conference to be held in San Diego on the campus of the University of California San Diego, The Metropole’s theme for February is San Diego. This is the second of four entries for the month. For more information about SACRPH 2024, see here. For other entries in the series click here.

In October 2023, local media outlets flashed the news that San Diego, California, had been rated as the “greenest city in America,” based on two dozen criteria ranging from greenhouse gas emissions to open space and urban agriculture.[1]

The news may have come as a surprise to members of San Diego’s environmental community who had been battling for years to create a greener metropolis. These included community planners contending for bike lanes; climate campaigners suing the city’s Climate Action Plan; San Diego’s Coastkeeper organization filing dozens of clean water actions; and perhaps most importantly, the persistent effort of Barrio Logan residents to restrict noxious businesses in their neighborhood, which was entering its seventh decade.[2] The limits of San Diego’s progress as a green city were obvious to those who knew it best.

Nonetheless, California’s second-largest city revealed not just the limits but the possibilities of building a truly greener city: a sustainable, equitable, and “natureful” ecosystem for people and wildlife.[3]

In many ways, San Diego is a model of the complex, hybrid “urban nature” idealized in environmental literature, a kind of green city in waiting.[4] But to the extent that this potential was emergent, it was not by accident. San Diego’s green footsteps were the result of insistent grassroots environmental advocacy over decades.

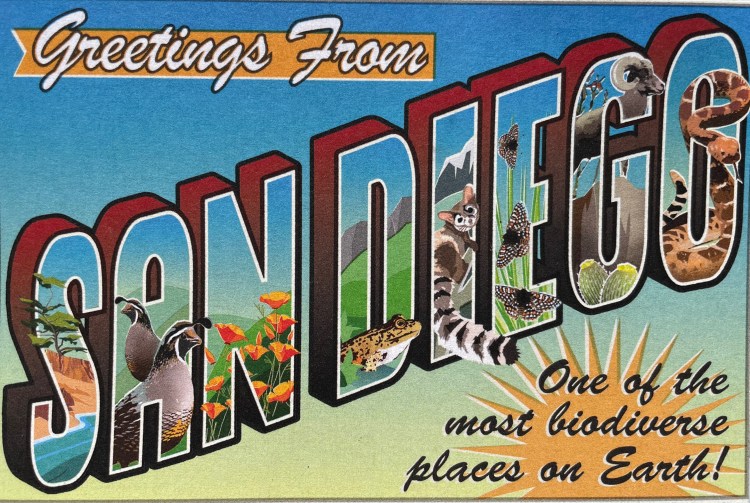

Contemporary San Diego is a diverse, sprawling, auto-dominant metropolis of 3.3 million. It shares a history of unequal development with other US cities, and these patterns are magnified by the legacies of Native displacement and militarization on the United States-Mexico border, which the city abuts. At the same time, San Diego was among the most biologically diverse metro areas on earth, and its rugged topography helped sustain “islands of nature in the middle of the city.”[5] Urban planners Kevin Lynch and Donald Appleyard concluded in their 1974 study “Temporary Paradise?” that San Diego’s landscape provided the template for a city uniquely integrated with nature.[6]

Indeed, the city became an incubator for green activism and a proving ground for environmental policy. This included vigorous movements for environmental justice, which shaped a new urban environmentalism infused with demands for biodiversity, climate resilience, cross-border justice, and equitable access to nature.

For urban historians, San Diego offers a map of modern environmental history and politics and the imprint of sustained and creative advocacy on a region.

Biodiversity Hotspot

The key context for this story was the city’s distinctive biophysical environment. The metropolis sprawls across a narrow coastal plain between the Pacific Ocean and the Laguna Mountains, which rise above 6,000 feet within 40 miles of the surf before plunging to sea level again in the Anza-Borrego Desert. Seen from space, the setting is clear. The metropolis huddles against the cold Pacific on a green ribbon of shore and chaparral, flanked by sun-baked desert that stretches for hundreds of miles.

Here, on this geographic knife’s edge, the interplay of shade, soil, slope, and coastal microclimates combined with a millennia of human choices to produce an unparalleled gathering of plants and animals. San Diego is “the most biologically rich county in the continental United States,” home to more bird species (over 520), more native plants (over 1,700), more endemics and more threatened or endangered species (over 200) than any US city.[7]

Equally important, wild, open spaces are woven throughout the metropolis, in a landscape of steep canyons and boulder-strewn hills interspersed with subdivisions. “Seen in an aerial photograph,” Cary Lowe and Eric Bowlby write, canyons “are everywhere in the city, incisions in the urban fabric created by rushing streams over centuries.”[8] San Diego is a place where owls hoot and bobcats prowl in the urban dusk, and endangered species lurk at the end of the block.

Environmental Innovator

This diverse terrain and the rich biodiversity that it supported made San Diego an innovative space for environmental ideas and action.

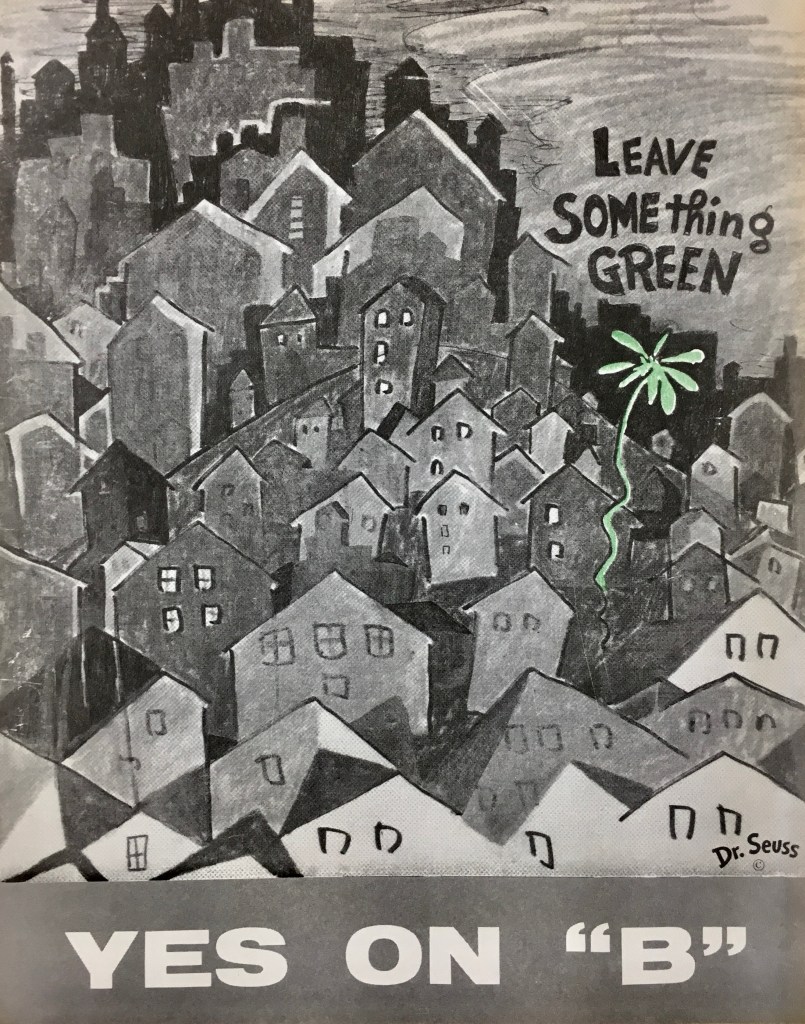

Contemporary environmental politics in San Diego emerged along two tracks in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In the booming North City, concerns over corporate-scale sprawl, endangered species, and the fiscal costs of growth coalesced in a right-leaning conservation movement fitted to the conservative city. Outdoor-oriented San Diegans elected a pro-environmental Republican, Pete Wilson, as mayor in 1971, and majorities supported creating a natural open space system, protecting California’s coastline, and managing growth to allow development but allocate costs away from local taxpayers.[9] San Diegans also contributed to California’s wider environmental upsurge, raising funds to save whales and redwoods as well as local canyons, demonstrating en mass on Earth Day, and establishing alternative institutions to support recycling, organic food, and native plants. Through the 1970s, San Diego became a leader in “growth management,” seeking a conservative path that would balance environmental protection and private profit, a local habit that environmentalists would challenge with mixed results in the decades to come.

Environmental Justice

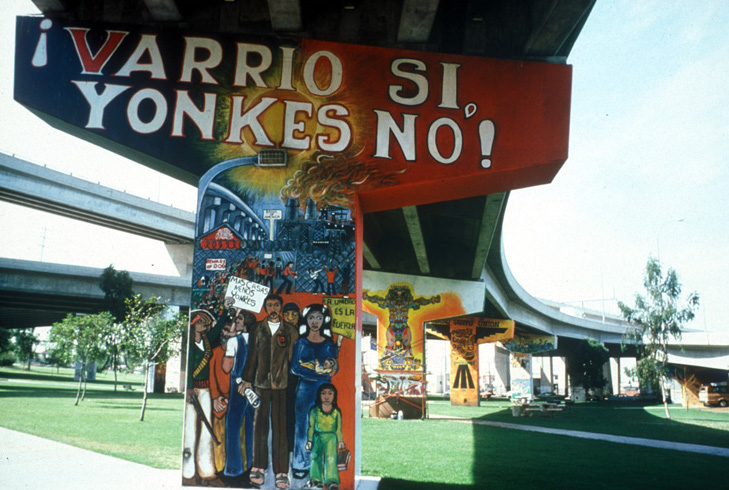

In the same moment, the unequal landscapes of Southeast San Diego sparked new movements for environmental equality. Historically, the region’s big money interests in maritime trade and national defense had sunk roots around San Diego Bay. Adjoining communities, such as Logan Heights, Barrio Logan, and National City, attracted growing communities of color, even as a divided housing market locked African American, Latino, and Asian American families out of other neighborhoods and redlining strangled investment. Local activists mobilized for jobs and housing in these neighborhoods in the 1960s. By the early 1970s, these politics took an increasingly environmental turn.

One emblematic protest erupted on Earth Day 1970, when Chicano activists seized land beneath the newly constructed Coronado Bay Bridge in Barrio Logan. Home movie footage shows residents with picks and shovels turning the land into a self-declared “Chicano Park.”[10] Artists famously appropriated the towering bridge supports, creating one of the largest collections of community murals in the world. Through the 1970s, the park evolved as a space for neighborhood celebrations and protest, including efforts to expand the park “All the Way to the Bay” and shut down polluting businesses. Several dozen junkyards—or “Yonkes”—that operated cheek by jowl with local homes were a point of particular contention.

These mobilizations set the stage for a coming environmental justice movement. In 1981, reports that waste haulers were dumping toxic chemicals in the barrio spurred the formation of a new group, the Environmental Health Coalition (EHC), which became one of the first and most influential environmental justice groups in California.[11] For cofounder Diane Takvorian, a social worker who had recently established the “Coalition against Cancer,” reports of toxic dumping sparked an insight that Robert Bullard would later conceptualize as “environmental racism.” “It occurred to me,” Takvorian said, “that people were essentially being discriminated against with the use of these hazardous materials.”[12]

EHC grew rapidly in the 1980s. The group was among the founders of the statewide Toxics Coordinating Project. Its fearless advocacy for “Healthy Communities,” toxic disclosure laws, and a “Clean Bay,” put it at odds with some of the city’s most powerful players—the Navy, Port District, and bayfront employers.[13] EHC documented local health disparities and “chemical hotspots,” shining a light on environmental injustice that contrasted with the booster image of “America’s Finest City.” These efforts led the group to develop a more holistic sense of the “environment” than conservation-oriented environmental groups, a vision that included the urban landscapes where people lived, worked, and played.

Early on, EHC recognized the need to “empower impacted communities to ‘speak for themselves.’”[14] In the 1990s, EHC broke ground in transnational organizing, working with members of Tijuana’s Colonia Chilpanchingo to sanction US polluters that sought to evade US environmental law in Mexico. It helped negotiate a landmark binational clean up agreement in 2004.[15] Since the 1990s, EHC has graduated more than 2,000 residents of San Diego frontline communities through its SALTA (Salud Ambiental Lideres Tomando Accion) leadership training program, building an infrastructure for environmental justice that would shape San Diego in the years to come.

Conserving Urban Biodiversity

Even as activism swirled around San Diego’s human environments in the 1980s and 1990s, the region’s diverse ecology attracted scientists and biodiversity activists who pushed the boundaries of environmental science, policy, and planning.

San Diego’s unique landscape supported foundational research in the field of conservation biology through the work of San Diegan Michael Soulé and colleagues. Biodiversity activists, too, used San Diego’s rich natural resources to test the limits of the Endangered Species Act. Planners and politicians responded with a new metropolitan template for habitat protection through Habitat Conservation Planning.

Exploring the region’s canyons and tidepools as a young person, biologist Michael Soulé participated in the city’s sprawl wars in the 1970s.[16] During the 1980s and 1990s, he and coauthors applied insights from island biogeography to the city’s urban canyonlands. In a landmark study, they found that species diversity was greatest in canyons where natural connections to other habitat enabled animals to range and repopulate. Their work illustrated that biodiversity depended not just on habitat size but on connection between habitats and on species relationships within them.

In the context of environmental policy at the time, these insights supported an important shift in emphasis from species to habitats. They also demonstrated the significance of urban nature as critical wildlife habitat and the potential for science-based conservation to manage it.

Soulé’s San Diego work represented a test case for the new field of conservation biology‚a marriage of science and advocacy—which he helped to establish and which impacted conservation efforts worldwide.[17]

Biodiversity Activism.

In the 1990s, local biodiversity activists prodded environmental policy in the same direction. Building on scientific research, advocates influenced by Earth First! activist Jasper Carlton began flooding federal wildlife agencies with Endangered Species Act (ESA) petitions to protect previously little-known species.[18] In San Diego, twenty-year-old David Hogan was inspired by the work of San Diego State University biologist Ellen Bauder, a specialist on ephemeral wetlands known as vernal pools that were home to some of the region’s rarest species. In the early 1990s, Hogan petitioned for Endangered Species Act protection for more than two dozen rare plants and animals.[19] The addition of one, a little gray bird known as the Coastal California Gnatcatcher (Polioptila californica), to the Federal Endangered Species list in 1992 sparked an earthquake in environmental planning.

Habitat Conservation Planning

As it happened, the Gnatcatcher’s native habitat—an aromatic ensemble known as Coastal Sage Scrub—coincided with the region’s most valuable real estate. The bird’s listing as a threatened species under the ESA set the stage for a development shutdown in coastal southern California. In response, big developers, public officials, scientists, and a handful of environmental groups worked out a novel compromise: an endangered species preserve sufficient to prevent the extinction of the Gnatcatcher and eighty-five associated species, but which also allowed for the bulldozing of habitat outside the preserve to continue. In 1997 San Diego’s Multiple Species Conservation Program (MSCP) became the first metropolitan-scale Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) approved under the Endangered Species Act and a template for dozens of metropolitan HCP’s to follow.[20]

The MSCP identified a future preserve of 52,000 acres of “biologically viable habitat lands” in the city of San Diego, plus an additional 120,000 acres in adjoining jurisdictions. The MSCP sought to “strike a critical balance between development and the protection of valuable habitat.” Significantly, the MSCP applied the insights of Soulé and his colleagues, prioritizing an “interconnected, contiguous preserve” of “habitat cores” and “wildlife corridors” to connect them.[21] The final preserve included many of the canyons that Soulé’s team had studied in the 1980s.

The result was a National Park-scale habitat preserve in the midst of the metropolis, a place with greater biodiversity than the Everglades and more visitors than Yosemite.[22] Although many environmentalists initially opposed the plan, calling it a program of “habitat triage,” the preserved lands in the MSCP became ever more precious as sprawl eroded the region’s rural fringe, and activists rallied around what was left.[23] In the years that followed, the MSCP anchored not only native biodiversity but the city’s open space system, including recreational opportunities and access to nature for communities across the city.

Nature for All

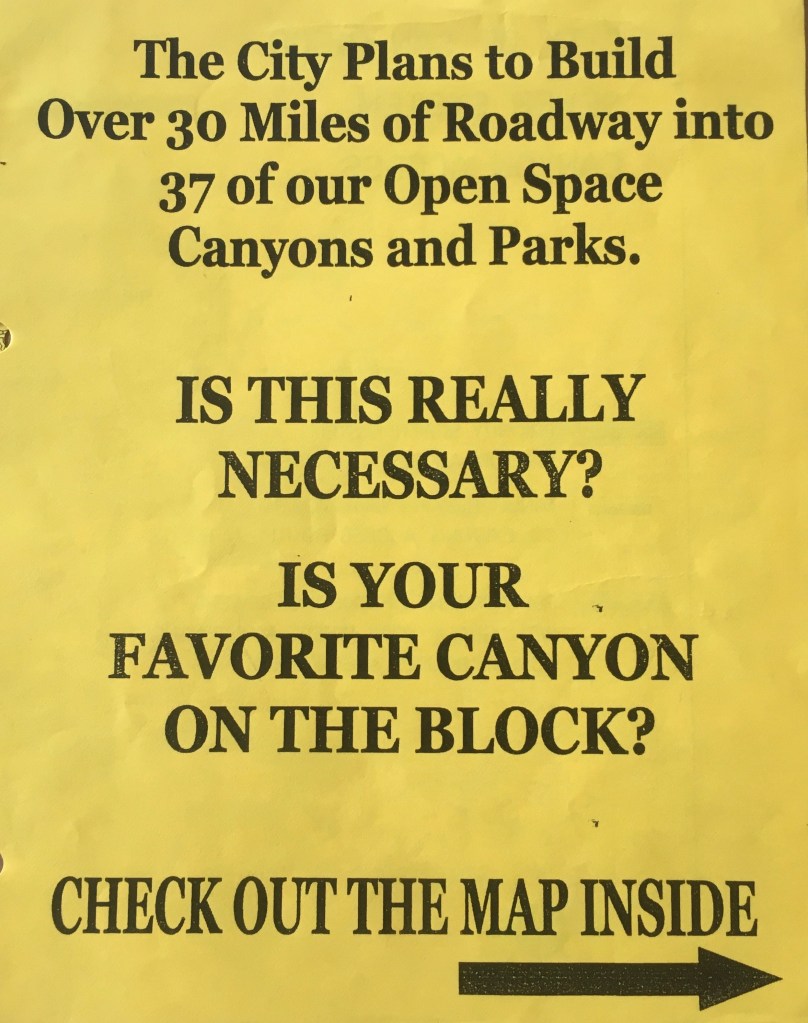

At the turn of the millennium, new movements for urban nature blossomed around the United States, bringing together the separate tracks of twentieth-century environmentalism—focused around conservation and justice—more fully than before.[24] San Diego continued to play an influential role. In the early 2000s, a grassroots campaign for nearby nature surged through the city, mobilizing around urban places as important human and ecological spaces. Ignited by municipal plans to pave sewer access roads through three dozen neighborhood canyons and bolstered by passage of the MSCP, the movement united community and environmental activists across the city’s canyon topography.

By 2005 the movement included more than thirty local “Friends of Canyons” groups, which mobilized to protect and restore local green spaces. Groups hosted events to “get people into the canyon”: star parties, bird box building, acorn gathering, trash clean ups, trail rehab, school nature walks, community art, and habitat restoration.[26] These activities enhanced local connections to nature even as the wider effort connected communities across the city’s social divides. Activists in San Diego’s more diverse communities pushed conservation-minded leaders from mostly-white neighborhood groups to address access and equity head on. The movement’s umbrella organization, San Diego Canyonlands, took on this challenge, emerging as an important bridge between conservation and social justice impulses in the local environmental movement.

A critical voice in this conversation was writer and San Diego Union columnist Richard Louv. Louv had profiled the efforts of activists, scientists, and teachers “who believe, against the odds, that cities can grow without turning everything in their path into asphalt or drive-through espresso bars.”[27] Louv’s breakout book, Last Child in the Woods (2005), grew from these engagements. In it, he argued that children were becoming disconnected from nature, with deleterious impacts on their physical and mental health. He named the condition “nature deficit disorder.” [28] Louv called for immediate action to get children—and people of all ages—outdoors, and his work helped to catalyze an international movement for children in nature. In 2012 the International Union for the Conservation of Nature cited Louv’s work in its declaration that children have a human right to access nature.[29]

At home in San Diego, Louv’s work elevated the campaign for nearby nature. Carrie Schneider, the founder of Friends of Switzer Canyon, reflected that the book gave canyon activists “a framework to say why this was important, why urban parks mattered in the midst of everything else happening in the world.”[30] Louv’s work also reinforced the significance of an urban environmentalism committed to both conservation and environmental justice. Among its achievements, the canyon movement led the city to give permanent protection to more than 12,000 acres of city-owned canyonlands for people and wildlife.

Conclusion

San Diegans continued to advocate for a greener city in the 2010s and ’20s. New initiatives ranged from urban forestry and green infrastructure to climate action, park equity, food justice, citizen science, ocean education, and rewilding. The city achieved important milestones: in 2015 groups pushed it to adopt a landmark Climate Action Plan, committing to significant GhG reductions (at least on paper), and in 2014 the city approved plans for recycling a third of its water. These efforts share a focus on a more sustainable, equitable city that was a part of nature. They sought greater quality and durability for human environments even as they acknowledged that San Diego was vital to the ecology of the region. Critically, they approached social justice as essential to environmental health of all. As was true in the past, all were the fruit of persistent environmental advocacy—much of it at the grassroots.

Andrew Wiese is a scholar, teacher and activist whose work focuses on urban and environmental history. He is the author of Places of Their Own: African American Suburbanization in the 20th Century (2004) and co-editor, with Becky Nicolaides, of The Suburb Reader (2006 and 2016). His current research project is a history of environmental politics and policy in San Diego, California. Wiese serves on the board of his local community planning group and is active with several environmental groups. He is a Professor of History at San Diego State University.

Featured image (at top): Sometimes a postcard speaks a thousand words. “Greetings from San Diego: One of the Most Biodiverse Places on Earth,” postcard, 2023, San Diego Natural History Museum.

[1] Adam McCann, “Greenest Cities in America,” Wallethub, Oct. 4, 2023, https://wallethub.com/edu/most-least-green-cities/16246.

[2] E.g., Climate Action Campaign v. City of San Diego, Cal. Sup. Ct., Sept. 9, 2022, https://climatecasechart.com/case/climate-action-campaign-v-city-of-san-diego/; San Diego Coastkeeper, “Big News on the Tijuana River Sewage Crisis,” Dec. 23, 2023, https://mailchi.mp/sdcoastkeeper/give-4-clean-water-in-13905569?e=354b68915b.

[3] E.g., The Nature Conservancy, Envisioning a Great Green City: Our Vision for a Sustainable Urban Century, June 14, 2018; Susan M Wachter and Eugenie Ladner Birch, Growing Greener Cities: Urban Sustainability in the Twenty-first Century. (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008). Julian Agyeman, Introducing Just Sustainabilities: Policy, Planning and Practice. (Zed Books, 2013); Timothy Beatley, “Planning for Biophilic Cities: From Theory to Practice,” Planning Theory and Practice 17, no. 2 (2016): 295-300.

[4] The Nature Conservancy, Nature in the Urban Century, Nov. 2018, https://www.nature.org/en-us/what-we-do/our-insights/perspectives/nature-in-the-urban-century/.

[5] Priscilla Lister, “North Park’s Switzer Canyon Inspired Conservation Movement,” Uptown News, Aug. 26, 2009.

[6] Kevin Lynch and Donald Appleyard, Temporary Paradise? A Look at the Special Landscape of the San Diego Region, Alegria, Lewis, and Peralta eds., (San Diego/Tijuana: 2017), 3-12.

[7] San Diego grew upon the unceded territory of the Kumeyaay people, who shaped and managed its environment as a homeland for more than 5,000 years. The Nature Conservancy, “San Diego, California,” https://www.nature.org/en-us/get-involved/how-to-help/places-we-protect/san-diego-county/; “San Diego: Endangered Biodiversity Hotspot,” Saving Species, vol 1, 2018, San Diego Zoological Society, https://science.sandiegozoo.org/sites/default/files/Saving%20Species%202018%20Vol%201.pdf; San Diego Audubon, https://www.sandiegoaudubon.org/birding/local-birding-resources.html.

[8] Cary Lowe and Eric Bowlby, “A Treasured Gift from City Hall,” San Diego Union Tribune, Dec. 23, 2012.

[9] Andrew Wiese, “’The Giddy Rise of the Environmentalists’: Corporate Real Estate Development and Environmental Politics in San Diego, California, 1968-1973,” Environmental History 19 (Jan. 2014): 28-54.

[10] Sonia Lopez, “Chicano Park Takeover,” San Diego State University Special Collections, https://youtu.be/PmaEiRoQz2U?si=6-cgwdtdDAcZZmY8.

[11] Cliff Smith, “Toxic Wastes Dumped Here, Guard Posted,” San Diego Union, Sept. 20, 1981; “Anti Toxin ‘Voice’ Has Grown Loud,” San Diego Union, Aug. 25, 1991.

[12] Diane Takvorian, interview with Andrew Wiese, July 1, 2020; Robert Bullard, Confronting Environmental Racism: Voices from the Grassroots (South End Press, 1993).

[13] Environmental Health Coalition, “Our Story,” https://www.environmentalhealth.org/about/our-story/; Steve LaRue, “Chemical Hot Spots Threaten S.D. Bay,” San Diego Union, Jan. 18, 1987; Michael Richmond, “Campaign Starts to Clear Bay of Contamination,” San Diego Union-Tribune, July 6, 1987; “Future Projects Build Upon Past Successes” Toxinformer, Jan/Feb 1988. Sierra Club Papers, SDSU Special Collections.

[14] Diane Takvorian, quoted in “A Supportive Presence,” San Diego Union-Tribune, July 2, 2017.

[15] Diane Lindquist, “Toxic Legacy—Polluter Leaves Faint Tracks,” San Diego Union-Tribune, Apr. 6, 1993.

[16] David Inouye and Paul Ehrlich, “Michael Soulé (1936–2020): Founder of Conservation Biology,” Science 369 no. 6505 (Aug. 14, 2020): 777; San Diego Natural History Museum, “Excerpts from a Conversation with Michael Soulé,” Feb. 16, 2018, https://youtu.be/gLrUmVJlipM?si=uUhN8lnVj6GMMpIm.

[17] Jennifer McNulty, “Michael Soulé, Father of Conservation Biology, Dies at 84,” University of California-Santa Cruz, Newscenter, June 23, 2020.

[18] Douglas Bevington, The Rebirth of Environmentalism: Grassroots Activism from the Spotted Owl to the Polar Bear, (Island Press, 2009), 161-85.

[19] David Hogan, interview with Andrew Wiese, May 20, 2020; Audrey Meyer, Bird versus Bulldozer: A Quarter-Century Conservation Battle in a Biodiversity Hotspot (Yale University Press, 2021).

[20] The first regional Habitat Conservation Plan under California’s Natural Communities Conservation Planning Act, 1991, was signed in Orange County in 1996. It covered 37,000 acres. Marc Ebbin, “Is the Southern California Approach to Conservation Succeeding?” Ecology Law Quarterly 24 no. 4 (1997), 695-706.

[21] City of San Diego, Multiple Species Conservation Program, Final MSCP Plan, Aug. 1998, 3-1, https://www.sandiegocounty.gov/content/dam/sdc/pds/mscp/docs/SCMSCP/FinalMSCPProgramPlan.pdf; Jerre Stallcup, “Roar of the Gnatcatcher,” Conservation Biology Institute Blog, May 22, 2013; https://consbio.org/newsroom/blog/from-the-trenches-conservation-planning

[22] Sara Allen, “Managing Pressures on Urban Open Space Preserves,” State of Biodiversity Symposium, San Diego Natural History Museum, Feb. 2020.

[23] Tony Davis, “San Diego’s Habitat Triage,” High Country News, Nov. 10, 2003, https://www.hcn.org/issues/262/14355

[24] On the history of these separate environmentalisms, see Robert Gottlieb, Forcing the Spring: The Transformation of the American Environmental Movement (Island Press, 1993).

[25] Eric Bowlby, interview with Andrew Wiese, Apr. 14-15, 2020.

[26] Deborah Knight, interview with Andrew Wiese, 2018.

[27] Louv, “Quality of Life is in Eye of Beholder,” Union-Tribune, Aug. 19, 2001; Louv, “Taking Green Urbanism to the Prairie,” Union Tribute, June 20, 2004.

[28] Richard Louv, The Last Child in the Woods: Saving Our Children from Nature Deficit Disorder, (Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books, 2005).

[29] International Union for the Conservation of Nature, “Child’s Right to Connect with Nature and to a Healthy Environment,” WCC-2012-Res-101-EN, 2012.

[30] Carrie Schneider, interview with Andrew Wiese, Apr. 27, 2020.