Editor’s note: In anticipation of the Society for American City and Regional Planning History’s (SACRPH) 2024 conference to be held in San Diego on the campus of the University of California San Diego, The Metropole’s theme for February is San Diego. This is the first of four entries for the month. For more information about SACRPH 2024, see here. For additional entries in the series click here.

In 1867, Alonzo Erastus Horton attended a lecture on the promise of West Coast urbanization near his then home in upstate New York. One of the cities discussed, San Diego, came to Horton in his sleep, when he dreamt of “founding a great” metropolis. He rose from bed in the middle of the night, pulled out a map, and poured over the port of San Diego. When his wife awoke the next morning, he told her he was going to sell his goods and “build a city.”[1]

Though he never constructed the city of his dreams, Horton did help set into motion the Southern California metropolis’s stealth ascent into urbanity. He did so through his own physical additions to the city’s landscape, such as the Horton House, a nineteenth-century, hundred-room hotel meant to “bespoke the future of San Diego as a commercial center and tourist resort,” but Horton also contributed to the city’s theoretical existence. He, along with deputy county surveyor L. L. Locking, produced the Horton Locking Map in the late 1860s, a plan for San Diego that enabled residents and others to internalize “an urban identity.”[2]

City planner and landscape architect John Nolen built on this foundation when he moved to the city in 1908. The Chamber of Commerce, the city’s most powerful political organization, and its Civic Improvement Committee wanted a comprehensive plan for San Diego’s future development, and Nolen obliged. He felt the city had failed to capitalize on its strengths—its consistent weather, mix of coastal and desert landscapes, and its port—thereby remaining just “another shabby provincial town.” Emphasizing its Mediterranean climate and landscape, Nolen drew upon examples such as Naples for the development of its waterfront, Nice regarding its public gardens, Rio de Janeiro in terms of its harbor, and Buenos Aires for harmonizing its “boulevards and open spaces.” Nolen widened the city streets, situated plazas, squares, and open spaces across town, and ultimately established a plan that highlighted San Diego’s “seaside celebration of sun and sky, an urban arena for the Mediterranean encounter of line, color, warmth and spaciousness.”[3]

Nolen’s contributions to San Diego’s built environment did not translate into a cohesive plan of social and economic development. The reality is that for much of its late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century existence, the city’s history amounted to stories of “millionaires frustrated in their attempt to create a great metropolis,” notes Anthony Corso. “For many decades, San Diego was a nice place to visit, but certainly not a place to work unless one was willing to pick oranges.”[4]

To Corso’s point, prior to the Navy’s embrace of San Diego, and vice versa, San Diego seemed to be searching for an identity. As a result, many histories of the city rightly focus on its partnership with the Navy, a relationship that stretches back to the early twentieth century, when the “Great White Fleet” sailed into port with Teddy Roosevelt at the helm in 1908 during its fourteen-month “world tour.” Thousands of residents greeted the president and the US Navy. “Small boats of all descriptions surrounded the warships, and Sailors were pelted with blossoms by ‘Flower Committees’ and filled to capacity with free lemonade by ‘Fruit Committees.’” Sailors enjoyed four days of “the royal treatment” before departing for Los Angeles.[5]

However, despite its undeniable growing presence, for roughly the first two decades of the century, the Navy did not define the city’s identity. The city’s sunny disposition (the sun shines nearly three fourths of the year), its Mediterranean climate, and its proximity to the ocean and mountains made it a destination for tourists, mystics, and wellness advocates.

Writers, artists, and spiritualists gravitated to San Diego in small but significant numbers. Point Loma’s Raja Yoga School and Theosophical community, notably the latter’s “eerily beautiful buildings, its nature-based mysticism, its ambitious program in the arts, its sense of the Other side shimmering on the horizon of the Pacific—spoke to the collective San Diego identity in a way that leavened an otherwise ordinary American city with the mystical and the aesthetic.”[6] La Jolla occupied a similar, if more glamorous space, less spiritual more noir, in the post-World War II era. As one historian described it, “a combination of Carmel and a New England township. . .artsy and bohemian. . .the Hamptons of San Diego.”[7]

San Diego’s formal marriage to the Navy solidified in the 1920s, when it became the “Gibraltar of the Pacific.” Facilitated by metropolitan business leaders and the efforts of Congressman William Kettner, an aggressive lobbyist for military investment in the city, San Diego emerged as critical node in the nation’s barely nascent military industrial complex, which expanded exponentially following World War II.

Kettner established the foundation for the city’s position in this future matrix during the 1910s and 1920s. Elected in 1912, Kettner, the former director of the San Diego Chamber of Commerce, immediately paid dividends by obtaining a $249,000 appropriation to pay for the dredging of San Diego harbor soon after taking office. When the Navy decided to split its fleet in 1919, placing a significant part at a West coast location, Kettner utilized his connections to San Diego’s business community and those he had established in Washington to deliver the Naval Training Station, the Naval Hospital, a Naval Repair Base, and a fleet landing to the city.[8]

Well before the centralizing expansion of the city during World War II, the Navy’s grip on the local economy was evident. In 1927 the Army and Navy spent $18,000,000 annually and counted $40 billion in holdings in San Diego.[9] By the early 1930s, nearly one third of the San Diego workforce was “one way or another on the Navy payroll,” observes Starr.[10] This development persisted over the course of the century. By the late 1980s, over 21 percent of the gross regional product of San Diego County was derived from defense spending, which was further supplemented by the expenditures of retired military personnel living in the area.[11] The “quintessential martial metropolis,” historian Roger Lotchin argues, San Diego “civilianized war” using “military resources to make itself into a great urban center.”[12]

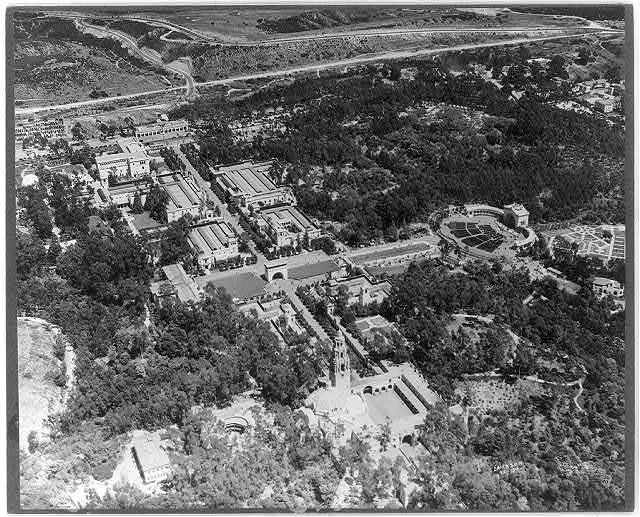

Kettner’s election and his subsequent lobbying served as manifestation of the city’s political leadership, a conservative, business-oriented oligarchy with Progressive Era, City Beautiful leanings. Balboa Park, set aside in 1868 to be preserved as parkland, embodied the City Beautiful aesthetic with the contributions of Kate Sessions, the first woman on the Pacific Coast to study agriculture, at the University of California Berkley. Sessions oversaw the planting of much of the flora found in the park today—over 20,000 plants, by some estimates. The park hosted both the 1915 Panama–California Exposition and the California–Pacific International Exposition of 1935, both of which celebrated the city as “the capital, the crossroads city, of Mexico, the Spanish Southwest, and the Pacific Basin.” Andrew Wiese, writing for Mapping Inequality, agreed but noted the celebration’s ideological construction marked “San Diego as a white city with a history rooted in Spanish and American conquest of the West.[13]

Though hardly a straight line, the City Beautiful influences, one might argue, persisted, emerging again in the late twentieth century in the region’s approach to development known as Growth Control, in which the city enacted environmental impact procedures city-wide to conserve local wildlife and flora, but to also slow development. By the end of the 1970s, attention shifted to “crime control” and in the Reaganite 1980s some residents pushed back on the environmental reforms. However, at the same time, grassroots environmental groups emerged such that by October 2023 the city earned the designation of Greenest City in America.[14]

In general, however, for much of the twentieth century, the city’s political leadership drew from the arrival of folks like Horton and William Ellsworth Smythe, both men early civic and economic leaders of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Horton and Smythe were followed by Hawaiian sugar magnate John Spreckels, Ulysses Simpson Grant Jr. (son of President Ulysses S. Grant), and Edward W. and Ellen Browning Scripps, who were then followed by Roger Revelle and C. Amholt Smith, among others.

Political debates regarding the city’s future often hinged on the idea of “Smokestacks v. Geraniums.” Should San Diego remain a resort/artist community akin to Santa Barbara, or should it embrace metropolitan reality and look to industrialize? From the 1917 mayoral race forward, this dynamic undergirded most discussions regarding the municipality’s trajectory.

Even after the Navy’s ascendence, in the late twentieth century debates about the city’s economic future still foundered on this argument. In 1995 the San Diego Association of Government’s (SANDAG’s) chief economist suggested that the city and county attempt to draw more manufacturing to the region. Tourism failed to produce entry level positions as lucrative as those offered by manufacturing argued SANDAG economist Marney Cox, who was roundly denounced for his comments.[15] While the city’s oligarchic leadership remained dedicated to making San Diego a global city, they did not agree on which path to follow.

The original decision to court the armed forces grew from dismay over perceived radicalism, though one should refrain from assuming it was strictly an elite-driven decision. “San Diegans as a whole understood quite clearly the close connection between the city and the sword,” argues Lotchin. “They were not manipulated by some greedy elites, but rather were quite willing participants in the creation of the fortress city.” The 1912 Free Speech battles between the Industrial Workers of the World and the city descended into rancor, loud demonstrations, and occasional violence, unsettling elites and rank-and-file San Diegans, alike. Emma Goldman’s manager, Dr. Ben Reitman, was abducted, beaten, branded, and tarred by the city Vigilance Committee.[16] The city’s police chief denounced the IWW and rode around town “with a rifle and a beltful of cartridges. . .a precaution he said he never had taken before,” reported the San Francisco Chronicle in May of 1912.[17] The general chaos and disturbance brought by the conflict convinced the city’s political leadership and residents that industrialization brought radicalism, hence the increased push for naval investment. The Navy’s exclusion of African Americans was largely viewed by elites and the public as a benefit, since the city was over 90 percent white in 1930 and generally embraced segregation and racial discrimination in its own customs and policies, such as redlining.

“Boston of the Pacific”

World War II reshaped the city as it boomed in population, going from 203,000 in 1940, to 390,000 during the war, and finally settling in at 334,387 by mid-century . The build-up of military and aviation industries reshaped not only the city’s built environment, but also its human demographics.

Though nearly all of the city’s oligarchs tended to a business-oriented conservatism, Edward W. and Ellen Browning Scripps did not. Having earned their money from overseeing a journalism empire, the brother and sister team leaned to the left and funded intellectual pursuits in the region, such as their 1912 establishment of the San Diego Marine Biological Institute, later affiliated with University of California San Diego and renamed the Scripps Institute of Oceanography.

Roger Revelle, a world-renowned scientist and eventual director of the Scripps Institute, served as one of the city’s mid-century leaders. He espoused his own beliefs about San Diego’s future, putting forth San Diego as the “Boston of the Pacific,” a reference to the East Coast city’s history of education and its concentration of universities. Revelle envisioned the potential for the agglomeration of science and technology research and application. The military, the aviation industry, and local political leaders agreed: San Diego needed a version of Pasadena’s Cal Tech. In response, the city donated roughly eight hundred acres to the creation of the University of California San Diego.[18] The trend continued when in 1960 the city donated twenty-seven acres to the creation of the Salk Institute, which opened its doors on the UCSD campus in 1963.

The atomic age and Cold War demanded a large, technologically savvy military force. The same was true of Convair and other aviation companies that settled in San Diego. The addition of UCSD and its focus on science and technology furthered such developments. As historian Roger Lotchin notes, UCSD was never meant to serve the masses, but rather, as the city’s newspapers put it, it was to serve as “an atomic age graduate school,” “ultrasonic, intercontinental, fissionable, fussionable.”[19] Residents no longer consisted predominantly of midwestern transplants and retirees; this concentration of such a highly educated and professionalized work force, evident as early as 1944, “helped [to] establish a distinctive urban culture that would eventually tender San Diego highly receptive to science and technology at its most innovative.”[20]

Mid-Century Urban Redevelopment

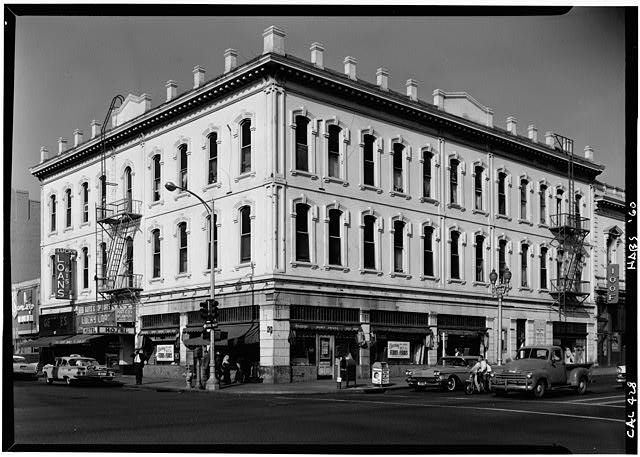

During the early twentieth century, San Diego never endured the kind of urban pressures that afflicted many Midwestern and East Coast cities at that time; the city had neither an influx of immigrants from Europe or Asia, nor did it absorb large numbers of the rural poor. At mid century there was no declining downtown core, at least not on the level of its counterparts to the East, to demolish.[23] During the 1930s and 1940s, the city had developed an “unsavory Prohibition era reputation as a ‘wide open town.’” The Navy’s presence and the city’s proximity to Mexico meant that while beaches, the zoo and Balboa Park drew tourists, gambling and prostitution did also. In order to address this issue, the city, using federal and state funding, embarked on a thirty-year downtown redevelopment plan which eliminated the old red light and hotel district and included a convention center and visitor’s concourse.

The idea was to shift “commercial life to the northern suburbs,” notes historian Susan Davis.[24] Mission Valley, north of downtown, emerged as a location for a constellation of resort hotels, shopping malls, and a sports stadium by the mid-1960s. New freeways and an interchange connected it to the city’s older beach communities. Sea World opened in 1964 and acted as commercial anchor and economic stimulus.[25] This dual development strategy paid dividends for Mission Valley but undermined efforts to revitalize downtown. Such a program was hardly unique to San Diego; Los Angeles had embraced a similar development strategy in the 1950s with very similar results: growing regional shopping centers juxtaposed with a declining downtown.

While the city did not develop or utilize urban renewal in all the same ways as its Midwestern and Eastern counterparts, housing segregation was just as ensconced. Freeway construction and housing policy hemmed in the city’s two largest minority communities. Black San Diegans lived in Southeast San Diego, while the city’s Chicano community populated Logan Heights, Golden Hill, and City Heights. I took time for the city’s Latino community to assert its power as a political force; perhaps the best illustration of its organization is Chicano Park, a space in Barrio Logan created in protest during the 1970s over the city’s attempt to turn the site into a police station. It is now home to world-class murals and a site of solidarity for San Diego’s Latino community.

Caveats in 21st-Century San Diego

As Mike Davis and others have noted, the military is not monolithic, particularly after 1945. During the Cold War, the United States maintained a large standing military with a notable emphasis on naval power, which was increasingly dependent on career noncommissioned officers (NCOs) and enlisted personnel, both of which often had families. Moreover, the armed forces, after 1948, integrated faster than the larger society, meaning each decade the military and its enlistees grew in their diversity.

Tensions between the more working-class enlisted members and NCOs and the officer class that dominated San Diego board rooms and its civic culture sometimes surfaced. Housing serves as a window into this conflict.

In order to address one of the primary issues facing the growing number of military families, housing, the Navy attempted to build homes for enlisted personnel and their loved ones. These efforts provoked opposition from the real estate industry in the 1950s and 60s and later from homeowners during the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. Middle-class homeowners spoke about military housing in similar terms to those opposing public housing.[26] Opposition to military housing often failed to thwart efforts, and due to the military’s increased diversity, several of San Diego’s more integrated neighborhoods—Linda Vista, Tierrasanta, and Paradise Hills—contain or were spawned by military housing.[27]

However, this opposition to military housing, though a result of several convergent factors beyond the scope of this overview, underscores San Diego’s ideological paradox: California’s second largest city never really saw itself as a sprawling metropolis.

Historian Anthony Corso labeled it the “anti-city.” “The majority of citizens maintained a posture of rejecting outsiders—be they new businesses or tourists,” he wrote in 1983.[28] Kevin Starr concurred: “San Diego had always been a city that sustained within itself an anti-urban impulse, a city that wanted to be urban and suburban—pastoral at one and the same moment.”[29]

Such metropolitan attitudes shaped the city’s economy, pushing industrialization to the Mexico-US border during the 1960s. However, when business leaders sought greater economic integration with its sister city in Mexico, Tijuana, in the decades that followed, homeowners viewed the “forces of modern globalization as potential threats to middle-class quality of life,” notes historian Daniel Elkin. “San Diego’s long-incubated civic culture, centered as it was on aversion to threats to homeowner quality of life, proved a consistent obstacle, and one that forced the city’s Chamber of Commerce to constantly adapt.”[30]

Twenty-first-century San Diego, for its calm exterior, is a city of extreme juxtapositions: surf haven, military outpost, biotech center, and a “high traffic site of smuggling contraband.” “It’s not just a military town; it’s the most military. It’s meth problem isn’t just bad; it’s the worst,” notes writer Jordan Kisner. Yet, much of it remains tucked away amid the region’s Mediterranean landscape and highways. The military’s undeniable presence remains surprisingly inconspicuous. “Everyone knows there’s a naval base on Coronado. . .but you don’t see it. Instead, you see the Victorian Spires of Hotel Del, where Marilyn Monroe shot Some Like It Hot.”[31]

Looking back over its twentieth-century history, San Diego’s current three-legged economy, based on tourism, biotech, and the military, in many ways seems an echo of its emergence nearly a century ago. The strength of its grassroots environmental movement and Green City bonafides is arguably an extension of its early City Beautiful leanings and general interest in conservation. The establishment of what became the Scripps Institute encouraged pursuit of other science and technology ventures that resulted first in the creation of UCSD and later in the development of a thriving biotech industry. Throughout, anti-urban biases, held by residents and leadership alike, created tension within a growing metropolis that did not see itself in those terms, yet the city grew. It might not have turned out to be the dream that Horton envisioned in 1867, but it’s a living reality that includes over 3.3 million souls within its metropolitan reach.

As usual, our list below is simply a starting point and not meant to be comprehensive. We welcome suggestions in the comments.

Bibliography

Davis, Mike, Kelly Mayhew, and Jim Miller, Under the Perfect Sun: The San Diego Tourists Never See (New York: The New Press, 2005).

Camarillo, Albert. Chicanos in a Changing Society: From Mexican Pueblos to American Barrios in Santa Barbara and Southern California, 1848-1930 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1979).

Corso, Anthony W. “San Diego: The Anti-City,” in Sunbelt Cities: Politics and Growth since World War II, eds. Richard M. Barnard and Bradley R. Rice (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983).

Delgado, Kevin. “A Turning Point: The Conceptualization and Realization of Chicano Park.” Journal of San Diego History (Winter 1998), https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1998/january/chicano-3/ .

Bridges, Amy. Morning Glories: Reform in the Southwest (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999).

Davis, Susan G. “Landscapes of Imagination: Tourism in Southern California,” Pacific Historical Review 68, no. 2 (May 1999): 173-191.

Elkin, Daniel. “Backlash on the Border: Conservatism and the Rise of the New Economy on the San Diego-Tijuana Corridor,” Journal of Urban History, vol 46, no. 3 (2020): 561-578.

Fusch, Richard and Larry R. Ford. “Architecture and the Geography of the American City.” Geographical Review 73, no. 3 (July 1983): 324-340.

Griswold del Castillo, Richard. “The San Ysidro Massacre: A Community Response to Tragedy.” Journal of Borderlands Studies. III:2 (Fall 1988): 65-80.

Guevarra, Rudy P. “’Skid Row’: Filipinos, Race, and the Social Construction of Space in San Diego.” Journal of San Diego History 54, no. 1 (Winter 2008): 1-15, https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/v54-1/pdf/OnLineJournal54_1.pdf.

Hasegawa, Susan. “Americanism and Citizenship: Japanese American Youth Culture of the 1930s.” Journal of San Diego History 54, no. 1 (Winter 2008): 1-15, https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/v54-1/pdf/OnLineJournal54_1.pdf.

Jenson, Joan M. “The Politics and History of William Kettner,” Journal of San Diego History 11, no. 3 (June, 1965), https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1965/june/kettner-2/.

Kisner, Jordan. “Welcome to San Diego,” in City by City: Dispatches from the American Metropolis (New York: N+1, 2015).

Lotchin, Roger. Fortress California, 1910-1961: From Warfare to Welfare (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002).

MacPhail, Elizabeth C. Kate Sessions: Pioneer Horticulturist (San Diego: San Diego Historical Society, 1976).

Madyun, Gail and Larry Malone. “Black Pioneers in San Diego, 1880-1920. The Journal of San Diego History 27, no. 2 (Spring 1981), https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1981/april/blacks/.

Mallios, Seth. “Scientific Excavations at Palomar Mountain’s Nate Harrison Site: The Historical Archaeology of a Legendary African-American Pioneer.” Journal of San Diego History 55, no. 3: 141-160. https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/v55-3/pdf/v55-3mallios.pdf.

Morgan, Ruth. “The Allure of Climate and Water Independence: Desalination Projects in Perth and San Diego,” Journal of Urban History 46, no. 1: 113-128.

Reft, Ryan. “The Metropolitan Military: Homeownership Resistance to Military Family Housing in San Diego, 1979-1990,” Journal of Urban History 3, no. 5 (2017): 767-794.

Reft, Ryan. “The Privatization of Military Family Housing in Linda Vista, 1944-1956,” California History 92, no. 1 (May 2015): 53-72.

Rosales, Francisco. Chicano! The History of Mexican American Civil Rights Movement. (Houston: Arte Publico Press, 1997).

Saito, Leland T. “African Americans and Historic Preservation in San Diego: The Douglas and the Clermont/Coast Hotels.” Journal of San Diego History 54, no. 1 (Winter 2008): 1-15, https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/v54-1/pdf/OnLineJournal54_1.pdf.

Starr, Kevin. Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973).

Starr, Kevin. Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990-2003 (New York: Vintage Books, 2004),

Starr, Kevin. The Dream Endures: California Enters the 40s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

Starr, Kevin. Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance, 1950-1963 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

“Community Planning, Citizen Action, and Sustainability in a Southern California Edge City: San Diego’s University Community, 2000-2018,” Planning Perspectives 36, 2021, Issue 3, 495-513, Aug 2020

“Friends of Rose Canyon: The Politics of Place and the Environment in Twenty-First Century San Diego,” California History, 95, no. 3, (Fall, 2018), 2-20.

“‘The Giddy Rise of the Environmentalists:’ Corporate Real Estate Development and Environmental Politics in San Diego, California, 1968-1973,” Environmental History, 19 (Jan., 2014), 28-54

Wilson, Charla. “Why the Y? The Origin of San Diego’s YWCA’s Clay Avenue Branch for African Americans.” The Journal of San Diego History, 62, no. 3 & 4 (Summer/Fall 2016), https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/2016/july/why-the-y-origin-of-sd-ywca-clay-avenue-branch-for-african-americans/.

Featured image (at top): Cityscape San Diego, California, Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, (ca. 1980-2006), Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

[1] Kevin Starr, The Dream Endures: California Enters the 40s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 94.

[2] Starr, The Dream Endures, 95-96.

[3] Kevin Starr, Americans and the California Dream, 1850-1915 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1973), 401-403.

[4] Anthony W. Corso, “San Diego: The Anti-City,” in Sunbelt Cities: Politics and Growth since World War II, eds. Richard M. Barnard and Bradley R. Rice (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1983), 329.

[5] Mike McKinley, “Narrative” in The World Cruise of the Great White Fleet: Honoring 100 Years of Global Partnership and Security, ed. Michael Crawford, (Washington DC: The Naval Historical Center), 44-45; https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/research/publications/Publication-PDF/GreatWhiteFleet.pdf

[6] Starr, The Dream Endures, 101.

[7] Kevin Starr, Golden Dreams: California in an Age of Abundance, 1950-1963 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 68.

[8] Joan M. Jenson, “The Politics and History of William Kettner,” Journal of San Diego History 11, no. 3 (June, 1965), https://sandiegohistory.org/journal/1965/june/kettner-2/.

[9] Jenson, “The Politics and History of William Kettner.”

[10] Kevin Starr, Golden Dreams, 58-59

[11] Kevin Starr, Coast of Dreams: California on the Edge, 1990-2003, (New York: Vintage Books, 2004), 372.

[12] Roger Lotchin, Fortress California, 1910-1961: From Warfare to Welfare, (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002), 297.

[13] Starr, Golden Dreams, 57; Starr, The Dream Endures, 91-92.

[14] Corso, “San Diego: The Anti-City,” 338.

[15] Susan G. Davis, “Landscapes of Imagination: Tourism in Southern California,” Pacific Historical Review 68, no. 2 (May 1999), 190.

[16] “Vigilantes Plan to Work Boldly by Daylight,” San Francisco Chronicle, May 21, 1912.

[17] “Tar for Dr. Reitman, Emma Goldman Fled,” New York Times, May 16, 1912.

[18] Lotchin, Fortress California, 214-215.

[19] Lotchin, Fortress California, 214-215.

[20] Starr, The Dream Endures, 113.

[21] Starr, Coast of Dreams, 373, 377

[22] Jordan Kisner, “Welcome to San Diego,” in City by City: Dispatches from the American Metropolis (New York: N+1, 2015).

[23] Corso, “San Diego: The Anti-City,” 330, 333

[24] Davis, “Landscapes of Imagination,” 175-176.

[25] Davis, “Landscapes of Imagination,” 176-177.

[26] Ryan Reft, “The Metropolitan Military: Homeownership Resistance to Military Family Housing in San Diego, 1979-1990, Journal of Urban History 3, no. 5 (2017): 767-794; Ryan Reft, “The Privatization of Military Family Housing in Linda Vista, 1944-1956, California History 92, no. 1 (May 2015): 53-72.

[27] Reft, “The Metropolitan Military,” 780.

[28] Corso, “San Diego: The Anti-City,” 332.

[29] Starr, The Dream Endures, 113.

[30] Daniel Elkin, “Backlash on the Border: Conservatism and the Rise of the New Economy on the San Diego-Tijuana Corridor,” Journal of Urban History, 46, no. 3 (2020): 562.

[31] Kisner, “Welcome to San Diego.”

Just wondering who the author is of this article? Did I miss it listed somewhere?

LikeLike

We don’t usually list the author for our overviews, we consider it a sort of editorial voice, but usually the overviews are written by the blog’s senior co-editor Ryan Reft (me). When others write them we list the author.

LikeLike