By Ryan Reft

“The cost to the community of drug-related crime is staggering,” Chief Judge of the District of Columbia Court of General Sessions Harold H. Greene asserted to the United States Senate in June of 1970. Accepting more “conservative estimates,” Greene suggested that 10,000 addicts resided in the District of Columbia, spending “$40 to $50 a day on narcotics, and steal[ing] merchandise valued as much as $300 million per year.”[1] A 1978 report looking at four cities, including DC, suggested that in order to maintain their habit, the average heroin addict perpetrated 300 crimes annually.[2] Police Chief Jerry V. Wilson estimated that as much as 50 percent of the city’s crime was driven by heroin addiction.[3] While crime associated with heroin tended toward nonviolent infractions—larceny, burglary, robbery, and prostitution—rather than assault or homicide, Greene argued that these figures failed to capture the true human and societal cost, as residents feared for their public safety and the government’s ability to ensure it.[4]

As early as 1955, government reports indicated that DC’s emerging drug problem represented “a serious and tragic and expensive and ominous” development. However, within just over a decade, it exploded into a crisis. “Heroin began to devour the city’s poor [B]lack neighborhoods,” writes sociologist James Forman. By June 1969, nearly 50 percent of men newly incarcerated to the city’s jails had developed heroin addictions. In early 1970, the city estimated 5,000 addicts lived in DC; by the end of the same year, the number had grown to 18,000. In 1971 the city’s population included nearly fifteen times the number of addicts than in the entirety of England.[5]

Heroin use by both active-duty soldiers in Vietnam and returning veterans of the war further alarmed the administration, who saw the spread of addiction as an omen of larger disasters to come.[6] By 1970, Washington, DC’s struggle with heroin was a central talking point for local residents and even national figures, such as Nixon. Though the heroin outbreak had been largely limited to the Black community, it had already begun to spread into the white suburbs of Northern Virginia and Maryland. During the summer of 1971, senators from Virginia and Maryland acknowledged as much. “It is literally easier to find heroin or marihuana than to find a job, or almost anything else,” Senator Charles Mathias Jr. (D-Md.) noted in Senate hearings on the issue. “Drugs in the District has meant drugs in the suburbs.” Suburban affluence might have prevented the kind of outbreak of crime that devastated the city’s poorer Black communities, but heroin’s spread remained an issue. [7]

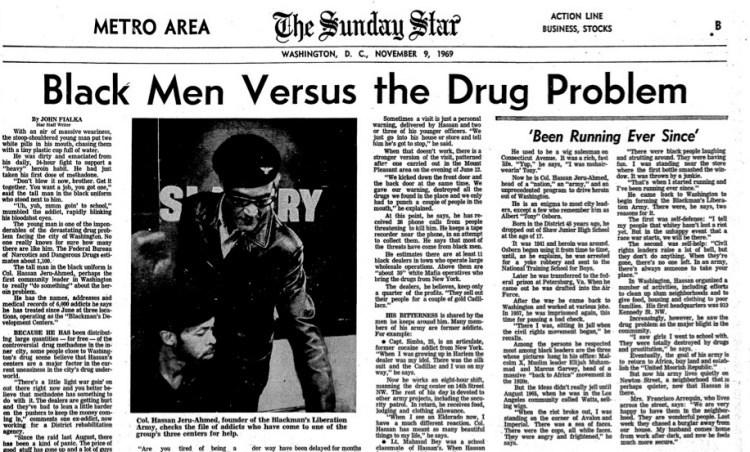

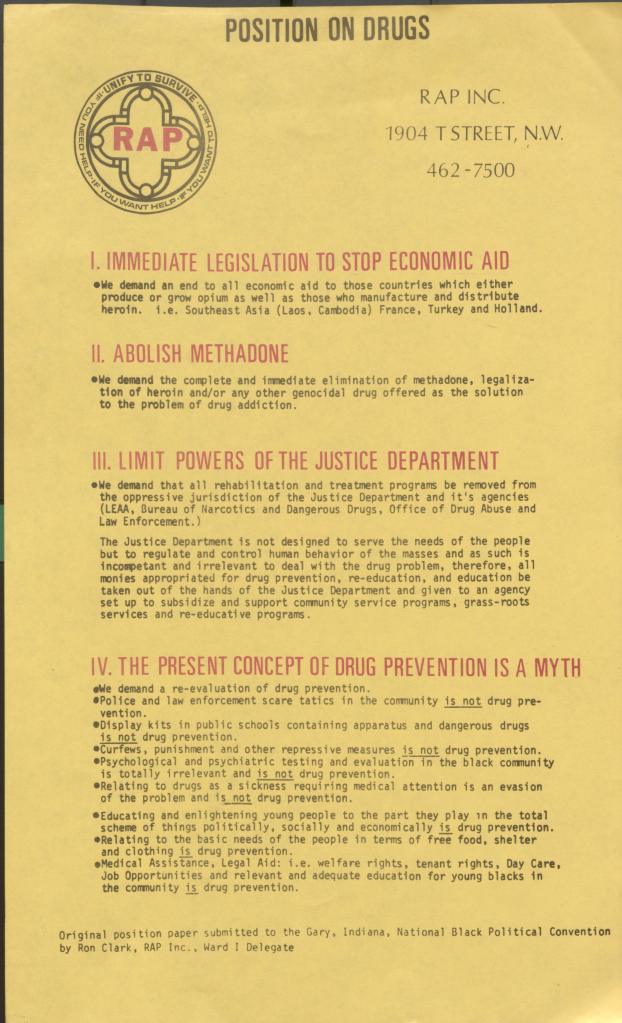

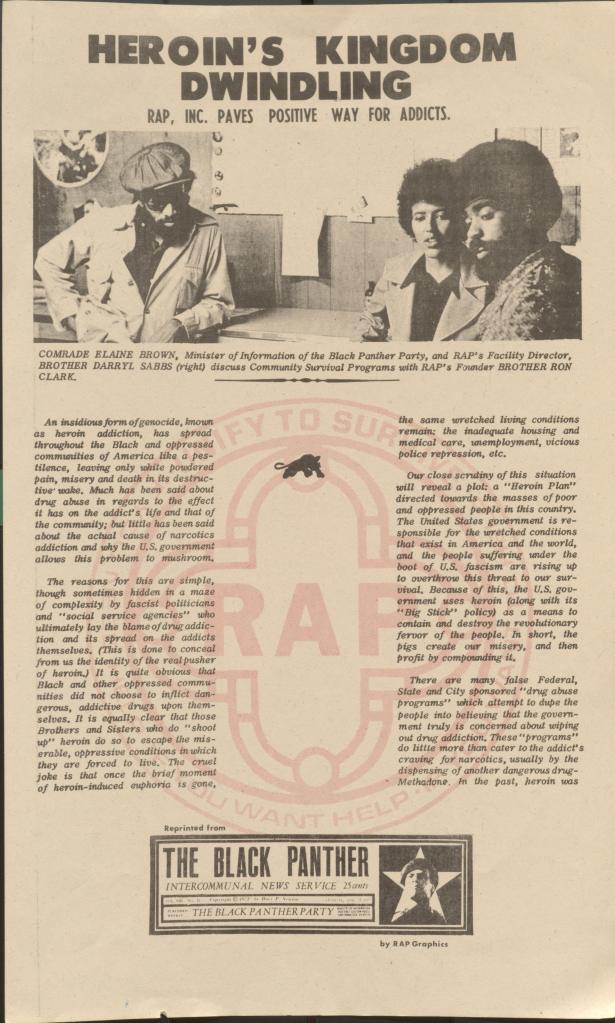

Heroin’s grasp on urban America, and especially the nation’s capital, throttled the nation. For years, the situation festered before emerging as an epidemic in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The federal government’s reaction proved slow, and in the District of Columbia, well before the national government addressed the growing problem, Black Washingtonians attempted to resolve, or at least mitigate, heroin’s destructive spread. The Black community responded to the epidemic in several ways. For example, RAP Inc., located in the city, had created a therapeutic community based on drug abstinence in 1970, and the Nation of Islam, having an established presence at Lorton Penitentiary in Virginia, worked with inmates to promote Islam while using religion to help addicts end their drug use.[8] However, Colonel Hassan Jeru-Ahmed and his Blackman’s Liberation Volunteer Army and the Blackman’s Developmental Center (BDC) emerged as both one of the earliest and most prominent actors, collaborating with federal and local officials to address heroin addiction for the city’s Black community and, eventually, its suburban white counterparts.

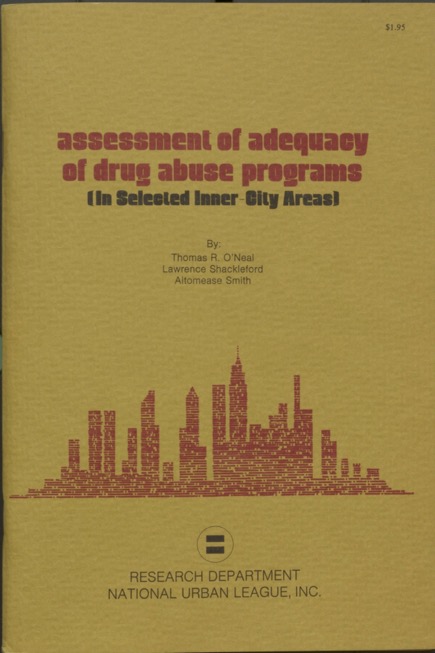

Equally important, the BDC was one of vanishingly few drug addiction treatment centers for inner city residents in the nation. Despite a 200 percent increase in the number of treatment programs since 1968-69, a National Urban League report on drug addiction programs found that nearly half the cities in its twenty-city study lacked even one drug treatment program for inner city residents. Moreover, the same number of cities lacked drug education and prevention programs altogether.[9]

The Federal Response

Richard Nixon had always hoped to use Washington, DC, as a laboratory for his policies. On the campaign trail, he lamented the city’s struggles with crime and freely deployed law-and-order rhetoric.[10] During his first year in office, he reorganized the city’s courts, appointed new judges, and expanded the police force. In the late 1960s, the city still lacked the power to govern itself; the federal government controlled most aspects of DC’s political life. Not until 1973, with the passage of the Home Rule Act, did residents begin to gain some control over their political fates, though even then it was severely restrained.

While Nixon reorganized the city’s jurisprudence and law enforcement, Senator Joseph Tydings held congressional hearings on the issue of drug abuse, and by February 1970, the government had established the Narcotic Treatment Administration (NTA) under the direction of Dr. Robert DuPont. Within only a few months of its establishment, the NTA was treating 1,500 patients, most receiving methadone or detox as outpatients. Two years later, the NTA operated thirteen outpatient and three inpatient facilities.[11]

Under the NTA, any adult who had been addicted to heroin for two years was eligible to receive “daily stabilization” methadone treatment from appropriate medical personnel. Due to the prevalence of criminality among addicts, one quarter of NTA participants found their way into the program through the courts.[12] NTA struggled to meet demand, as the number of addicts often overwhelmed its resources.[13] According to DuPont and Mark Greene, despite its struggles with overcrowding, the NTA had managed to treat two thirds of the city’s 18,000 addicts; 71 percent participated in “drug free or methadone detoxification programs aimed at abstinence within six months.” Local interdiction efforts by the city police, costing approximately seventeen million over three years, helped to decrease the supply of heroin, but also required three million annually, much of which went to its hundred-person narcotics team.[14]

The NTA was only one step. Alarmed by the prevalence of heroin use in Vietnam and in the hope of securing more votes for his 1972 reelection campaign, Nixon issued an executive order in June of 1971 creating the Special Action Office for Drug Abuse Prevention (SAODAP) as the treatment arm of his two-pronged drug abuse approach and appointed Dr. Jerome Jaffe to lead it. Jaffe was an influential leader in addiction therapy who had established a successful multimodal treatment center in Illinois, the Illinois Drug Abuse Program (IDAP). Multimodal approaches usually combined three aspects of treatment: methadone maintenance, therapeutic counseling, and detox.[15] Methadone proved the most controversial aspect of the treatment, since it did not solve an individual’s addiction but instead swapped a dependence on methadone for addiction to heroin. Still, maintenance curbed addiction and enabled addicts to return to a semblance of a normal life, find and keep a job, and thereby diminish crime.

At the time, however, proponents of therapeutic communities that embraced abstinence and utilized a combination of the “confessional approach of Alcohol Anonymous with the confrontational practices of encounter groups” and advocates for methadone maintenance viewed each other as apostates. The former saw methadone as a highly addictive “crutch,” while the latter saw therapeutic communities as “little more than penal colonies in which addicts were treated like ex-cons.”[16] Despite these conflicts, DuPont and Jaffe embraced the multimodal approach that incorporated both, in order to meet the needs of a heterogenous patient cohort.[17]

SAODAP was given authority to redistribute funding for agencies charged with demand reduction programs as well as free reign to rebuff the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), which also dealt with drug addiction, but the agency, critics argued, focused too little on drug addiction, notably among the working class and poor, and focused too much on middle-class, white neurotics.[18] From the outset, the Nixon administration set SAODAP’s parameters: “The goal. . .is not necessarily to make a man drug-free but to make him a job holding, law abiding, tax paying citizen.” SAODAP was always pitched as an emergency measure and, as such, was given a three-year lifespan.[19]

Black Nationalism, Law and Order, and Heroin

As innovative as the federal response was—one historian describes the 1970s as “the golden age” for federal drug treatment efforts—local actors preceded them and combined Black nationalism, law and order rhetoric, and addiction treatment.

The most prominent of these efforts was Blackman’s Community Development Center, an arm of Colonel Hassan Jeru-Ahmed’s Blackman’s Volunteer Liberation Army (BVLA). Hassan, born in 1925 in Washington, DC, and originally named Albert “Tony” Osborn, had dropped out of Shaw Junior High School at age seventeen. He developed his own addiction to heroin as a youth. Dabbling in property crimes landed Hassan at the National Training School for Boys before he was transferred to a federal penitentiary in Petersburg, Virginia. Eventually, he made his way into the Air Force during World War II. After returning to DC following the war, he was arrested in 1957 for passing bad checks. He again ended up in jail, where, according to Hassan, he delved into the work of Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X, and Elijah Muhammad, though none of their teaching gelled until the Watts Riot.[20]

Then living in Los Angeles, Hassan recounted his moment of inspiration to Evening Star journalist John Fialka. “I was standing near the store where the first bottle smashed the window. It was thrown by a junkie. . .That’s when I started running and I’ve been running ever since.” He again returned to Washington, DC, and organized the BLVA, staffed largely by ex-addicts like Hassan and with its first headquarters at 910 Kennedy Street, NW. In its initial years, the BVLA worked on a variety of projects such as “slum neighborhood” cleaning, improving housing, and food and clothing drives for poor families, but by 1968 Hassan had added informal, unarmed street patrols of the Mount Pleasant community, which the BLVA leader characterized as “a high crime neighborhood,” notably due to the spread of heroin use.[21] Local residents responded positively to the BVLA’s efforts. “We are very happy to have them in the neighborhood,” said Francisco Arrequin, who lived across the street from BLVA headquarters. “They are wonderful people. Last week they chased a burglar away from our house. My husband comes home from work after dark and now he feels much more secure.”[22] At its height, the BLVA counted 700 members.[23]

In conjunction with the BLVA, Hassan established a self-help community center known as Blackmans Development Center (BDC), where volunteers learned vocational and construction skills, working around the city for pay and reinvesting the profits in food and housing for participants and members of the BVLA.[24] However, the proliferation of addiction and his patrol’s increased encounters with addicts led Hassan to open a treatment center that utilized methadone in May of 1969.[25]

The BDC quickly took off, and through it Hassan melded law and order rhetoric, a rabid anti-drug message and Black nationalism that utilized equal parts back-to-Africa rhetoric and accusations of what would be called systematic racism today. BDC literature asserted that the government had allowed drug traffic to flow through Black communities; only with heroin, LSD and other drugs reaching white suburbanites had the government begun take an interest.[26]

Hassan also castigated Black drug dealers and the “white men” who brought the drugs from New York. The BVLA slapped “Stop Illegal Drug Trafficking” stickers across the city on lampposts, utility poles, and police and fire department boxes to such an extent authorities threatened them with legal action.[27]

The BLVA and Hassan went beyond verbal and symbolic critiques. In regard to local drug merchants, Hassan told reporters he and members of the BVLA first warned dealers to stop selling, and if they failed to abide by the request, the BLVA raided the premises. “We kicked down the front door and the back door at the same time. We gave our warning, destroyed all the drugs we found in the place, and we only had to punch a few people in the mouth.”[28] Such efforts carried costs, Hassan alleged he received over two dozen death threats, one of the BDC’s buildings was nearly destroyed by arson, and several members were shot—one left with a permanent disability while at least two others were killed. “There’s a little light war goin’ on out there right now, and you better believe that methadone has something to do with it,” one former addict confided to reporters. When arrested in 1973 for carrying a firearm in violation of city laws, Hassan told the court that due to his role in combating the local drug trade, a jail sentence meant he would “die in prison.”[29]

Though Hassan acknowledged systematic racism, he did not often criticize the police and actually collaborated with them. “The world doesn’t know all the specific cases on which [Hassan] has helped,” United States Attorney Harold J. Sullivan said in a court deposition crediting Hassan with the imprisonment of at least one prominent local drug dealer. According to Sullivan, Hassan volunteered himself to federal authorities after discovering the local dealer was targeting police and consented to wearing a wire. Sullivan described Hassan as “gutsy.”[30] During Hassan’s violation of the city’s gun laws in 1973, Hassan’s lawyer called on a plainclothes informant from the DC police force’s intelligence unit who had infiltrated the BDC in order to testify on Hassan’s behalf.[31] If local activists such as Douglas Moore and others wanted to increase the number of Black men and women on the police force, Hassan believed the police could not handle the challenge and conducted his own patrols with the BVLA.[32]

Black nationalism served as another feature of the BLVA. Hassan frequently spoke about his desire to return Africa. “The only relief for American Black Men is to earn with their minds, bodies, and blood, a land in Africa that can truly be called a nation,” he told the Philadelphia Tribune in 1967.[33] Later he established the United Moorish Republic, though over time the idea appeared more conceptual than real. Hassan described it as a “rallying cry for black philosophical unity [rather] than a concrete political entity.”[34] BLVA leaders reiterated this point to the media. “We’re involved in a revolution but it’s an intelligent revolution. It’s not a subversion to overthrow the government, but one to help black people become first class citizens in America,” said Captain Danyil Bey.[35]

In regard to decriminalization of drugs, like other Black leaders in the city at the time, Hassan believed the embedded racism of America meant that Black Washingtonians could not afford to use drugs or support legalization efforts, a view that many religious leaders and some council members, such as Douglas Moore, advocated at the time.[36] For example, Hassan opposed the legalization or decriminalization of marijuana in the capitol when it was proposed at the city council level in 1975.

Hassan’s establishment of a heroin treatment center at the BDC in May of 1969 preceded the creation of the NTA by nearly a full year. Hassan worked with Dr. Claude Walker, a graduate of Howard University medical school, who had begun writing methadone prescriptions for heroin addicts in 1967. “I knew I was outside the law, but where were they going to do? There was no local drug treatment program,” Walker told reporters. “I was doing it because heroin was crime related and there was no adequate program in the District to help these unfortunate people who want to help themselves.”[37]

Within its first six months, the BDC, operating four clinics across the city, registered six thousand people between the ages of eighteen and sixty-eight.[38] By August 1970, in addition to four clinics, BDC operated 121 halfway houses and had treated more then fifteen thousand addicts since its opening.[39] The BDC performed so well that federal and municipal peers utilized Hassan as an unofficial advisor to the Nixon administration’s efforts.

Federal Collaboration

A 1969 report by the Washington, DC, Department of Corrections documented the prevalence of heroin addiction among inmates by February of that year. Lamenting the spread of addiction, the report’s authors advocated for increased attention to the city’s “drug subculture and to build on these insights some strategies for dealing with the problem at its source—to devise, in other words, an effective strategy for prevention.”[40]

From the outset, Robert DuPont heeded such advice, understanding that in order to gain a grasp of the the city’s heroin epidemic, the NTA would need to find local collaborators. “I’ll work with church groups—anyone—who wants a piece of the action,” he told the Evening Star. Within a month of the NTA’s first clinic opening, DuPont met with Hassan, pointing out that the BLVA leader had established “the largest game in town. . .”[41]

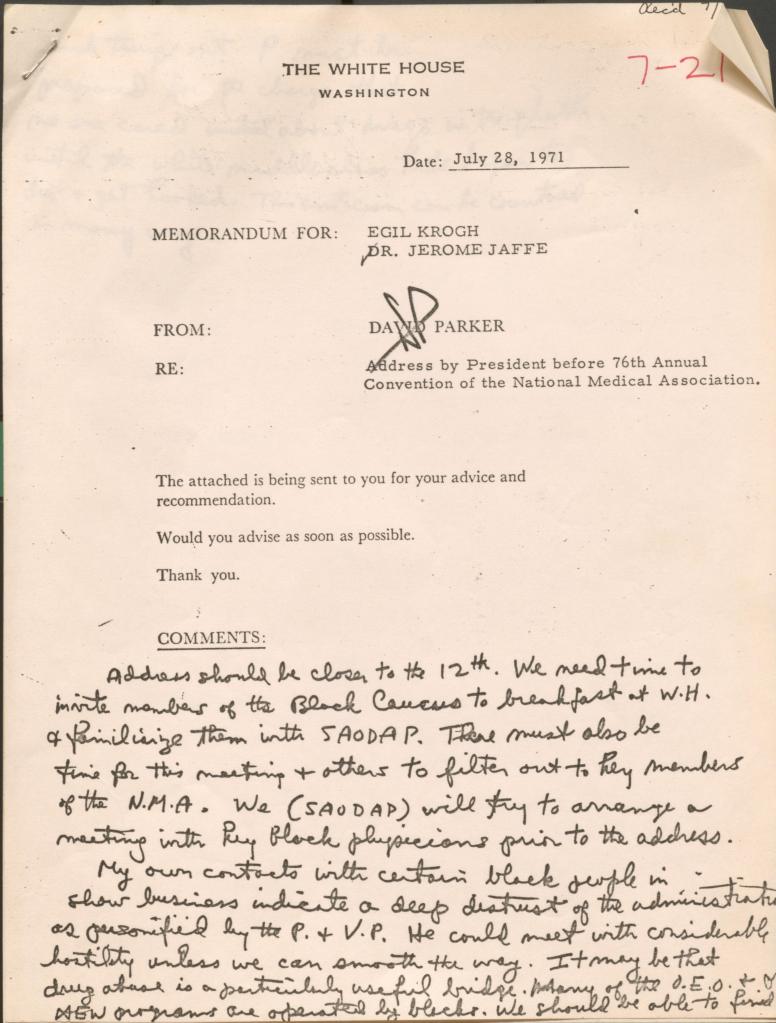

SAODAP leadership demonstrated a similar awareness. In a memo from Nixon official David Parker regarding the president’s upcoming speech to the National Medical Association, an organization consisting of Black medical personnel, Jaffe wrote at the bottom: “We need time to write members of the Black Caucus to breakfast at W.H. + familiarize them into SAODAP. There must also be time for this meeting + others to filter out to key members of the N.M.A.” Jaffe added that based on his contacts “with certain Black people in show business,” both the president and vice president Spiro Agnew generated a level of distrust in the Black community. The president “must be prepared for the charge that no one cared about drugs in the ghetto until the white middle class began to die + get hooked.”[42]

Jaffe’s observation was not necessarily new, as one Black woman told The Evening Star over a year earlier: “We didn’t see you here until the congressmen’s daughters and sons came home high, and they were found to be on horse. But you bet that they became interested in methadone after that. When horse spread to whites in the suburbs, then you and the government became interested.”[43]

Hassan, like DuPont and many BLVA members, questioned the efficacy of a singular focus on methadone treatment. The BDC model purposely sought to ween patients off heroin and methadone quickly, diminishing dosage more rapidly than other methadone maintenance programs. Hassan’s assistant, Capt. Danyil Bey, who himself had kicked a heroin habit just eight months earlier, critiqued the approach, calling the treatment a “crutch,” but admitted that most folks who came to the BDC dealt with methadone at some point.[44] DuPont agreed, noting that no silver bullet existed to solve the problem and that methadone represented just one of several options.[45]

Knowing this, the BDC used methadone in conjunction with a “comprehensive educational, vocational and social rehabilitation program oriented toward family structure,” warning that “Methadone Maintenance, callously operated to end crime by creating dependence upon methadone without regard for the drug dependent’s chance to rid himself fully from drugs, will fail in even the first objective.”[46]

According to BDC literature, new patients came to the organization through public school teachers and principals, St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, and even average patrol police who brought in or referred young patients. BVLA members attended court, where they interviewed prisoners and advocated for the courts to led the BDC assume responsibility for defendants. The courts, Judge Greene and others, often obliged, sending addicts to the BDC, sometimes instead of to the NTA or the city’s clinics, a point Greene noted in his remarks to Congress in 1970.[47]

Despite the Black nationalist rhetoric, Hassan saw the heroin crisis as a chance to mend racial fences. In late 1969, he urged the city to adopt his plan for economic revitalization job training in the city’s lower-income Black communities and advocated for including whites—“it’s the only realistic way of doing it,” he argued.[48] Roughly nine months later, Hassan spoke at a conference held in DAR Constitutional Hall. The event drew 750 attendees, including white suburbanites and inner-city Black residents, men and women, young and old. Hassan called for unity “between the races in combating illegal narcotics traffic.” DC Juvenile Court Judge Oliver Ketcham concurred; “’the Blackman’s Development Centers need and deserve the full support of the entire community,” he told the audience.[49]

Perhaps more telling, the BDC had begun to draw significant numbers of white drug addicts, with Hassan estimating that by January 1971 nearly 20 percent of their patients hailed from suburban Maryland and Virginia.[50] The BDC received contributions from musician Steven Stills and even collaborated with the Girl Scouts to combat drug abuse.[51] The National Urban League praised its efforts.

Though the BDC encountered critics in the local government and had their operations briefly suspended by city, ultimately Mayor Washington approved $144,000 in funds, much of which came from the Department of Justice’s Law Enforcement Assistance Administrative Act (LEAA), awarded to the BDC by the NTA in September of 1970. Soon after, the BDC received another $22,987 from Model Cities funding for “an intensified drug abuse preventive education program.”[52] In addition, a joint program between the US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) and the Department of Labor had awarded the BDC a one-year grant amounting to over $520,000 for vocational training, part of which was aimed toward former drug addicts.[53]

The BDC’s funding from the NTA benefitted from loose oversight. DuPont admitted that he had arbitrarily divided up LEAA funding between five community-based organizations in the city. Internally, DuPont recognized that the BDC was a high-risk proposition, constantly on the edge of insolvency, but that it was worth funding. Even after a government report noted that the BDC was performing well under its targeted goal, treating fifty-eight patients rather than the three hundred promised, DuPont sought to renegotiate the agreement, not to reduce funding but to reduce the number of patients, only to have Hassan refuse. Moreover, DuPont had been made aware of the BDC’s failure to implement adequate accounting measures, yet he still argued that the organization did treat some addicts and served as a useful source of information for the NTA. [54]

Congressional concerns regarding past antisemitic comments by Hassan triggered the audit, but NTA and SAODAP officials were undaunted by the poor accounting, possible mismanagement of funds, or the past antisemitism.[55] SAODAP and NTA had known by June 1971 about the BDC’s difficulties,and by that time the charges of antisemitism were in the open, yet in late September of 1971 DuPont encouraged the BDC to reapply for funding.[56] In the end, the BDC’s funding was pulled, and Hassan stepped down from his leadership position and, unsuccessfully, campaigned for the GOP nomination for the DC delegate to Congress.[57]

A few possibilities explain why DuPont would continue to recommend the BDC pursue funding. Even in its apparent diminished capacity, the BDC did still treat the city’s population addicted to drugs. It provided the administration with an example of direct aid to a Black-run facility. At that time, Hassan was among the city’s more notable charismatic leaders, appearing frequently on local television and radio. The NTA’s association with the BDC carried positive connotations for many residents. Additionally, knowing Hassan’s penchant for information gathering through the BVLA, the BDC might really have been a useful source of information regarding the city’s drug subculture, the same subculture about which the 1969 report on the city’s jails acknowledged local policy makers knew too little about.

In the end, interdiction internationally and locally, the establishment of the NTA and SAODAP, and the efforts of local actors like Hassan reduced heroin addiction across the city and contributed to a sharp drop in crime, though DuPont and others were careful to note crime rates stemmed from a complicated set of factors. Ultimately, DuPont and Greene concluded, “it is imperative that both treatment and law enforcement efforts be” deployed to reduce heroin addiction and, by extension, crime.[58] Yet it took the efforts of early actors like Hassan to address the needs of the very community being ravaged by addiction, particularly as evidence suggests that the federal government only became interested in heroin addiction when it began to seep into the suburbs and impact crime rates. The mix of Black nationalism, law and order rhetoric, and the multimodal approach by the BDC delivered treatment to a population desperately in need of it and managed to align with the Nixon administration’s politics.

Ryan Reft, PhD, is senior coeditor of The Metropole and editor of and contributor to Justice and the Interstates: The Racist Truth about Urban Highways (Island Press, 2023). He was also coeditor and contributor to East of East: The Making of Greater El Monte (Rutgers Press, 2020). His work has appeared in the Journal of Urban History, Southern California Quarterly, Boom California, and California History, as well as popular outlets such as the Washington Post, Zocalo Public Square, and KCET (Los Angeles).

Featured image: Col. Hassan Jeru-Ahmed pictured in an article for the Washington Evening Star, November 9, 1969.

[1] Harold H. Greene, Statement of Chief Judge Harold H. Greene District of Columbia Court of General Sessions Before the Senate committee on the District of Columbia, June 11, 1970, Box 62, Harold H. Greene Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[2] James Forman, Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America (New York: Fararr, Strauss, and Girousx, 2017), 26.

[3] John Fialka, “Black Men Versus the Drug Problem,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), November 9, 1969.

[4] Harold H. Greene, Statement of Chief Judge Harold H. Greene District of Columbia Court of General Sessions Before the Senate committee on the District of Columbia, June 11, 1970, Box 62, Harold H. Greene Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[5] Forman, Locking Up Our Own, 25.

[6] Grischa Metlay, “Federalizing Medical Campaigns Against Alcoholism and Drug Abuse,” The Milbank Quarterly 91, no. 1 (March 2013): 145.

[7] Drug Addiction and Treatment in the District of Columbia. Hearing before the Subcommittee on Public Health, Education, Welfare, and Safety of the Committee on the District of Columbia, United States Senate, 92nd Congress, First Session on The Problem of Drug Addiction and Treatment by District of Columbia Facilities, June 23, 1971, U.S. Govt. Printing Office Washington: 1972, 11-12, 8.

[8] Michael Anders, “Lorton Muslims Hold Bazaar,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), June 22, 1970; Thomas R. O’Neal, Lawrence Shackleford, and Altomease Smith, “Assessment of Adequacy of Drug Abuse Programs: In Selected Inner City Areas,” National Urban League Inc., 1973, 31, Box III:222, National Urban League Records, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[9] O’Neal, Shackleford, and Smith, “Assessment of Adequacy of Drug Abuse Programs”

[10] Kyla Sommers, When the Smoke Cleared: The 1968 Rebellion and the Unfinished Battle for Civil Rights in the Nation’s Capital (New York: The New Press, 2023), xii.

[11] Metlay, “Federalizing Medical Campaigns Against Alcoholism and Drug Abuse,” 142-144.

[12] Forman, Locking Up Our Own, 26; Robert L. DuPont and Mark H. Greene, “The Dynamics of Heroin Addiction,” Science 181, August 24, 1972: 716-722. “Robert L. Dupont and Mark H. Greene, “Heroin Addiction Epidemic,” November 22, 1972, 3, Jerome Jaffe Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[13] DuPont and Greene, 5.

[14] DuPont and Greene, 15, 17; interdiction abroad in Turkey and elsewhere also contributed to the decline of heroin use, but that is beyond the scope of this essay.

[15] Metlay, “Federalizing Medical Campaigns Against Alcoholism and Drug Abuse,” 142-144.

[16] Michael Massing, The Fix (Berkely, CA: University of California Press, 2000), 89,

[17] Forman, Locking Up Our Own, 26; Massing 89-92.

[18] Massing, The Fix, 104, 118.

[19] Metlay, “Federalizing Medical Campaigns Against Alcoholism and Drug Abuse,” 143-145.

[20] John Fialka, “Black Men Versus the Drug Problem,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), November 9, 1969.

[21] Fialka, “Black Men Versus the Drug Problem”; Claudia Levy Washington, “Black Unit Patrols Mt. Pleasant Area” Washington Post, May 31, 1969; Joe Mack Jr., “Trio Fights Dope Use in D.C.,” Chicago Daily Defender, January 16, 1971.

[22] Fialka, “Black Men Versus the Drug Problem.”

[23] Forman, Locking Up Our Own, 27

[24] Mack, “Trio Fights Dope Use in D.C.”

[25] Forman, Locking Up Our Own, 27.

[26] Blackman’s Development Center, “Drug Cure: The Humane Alternative to Blanket Methadone Maintenance,” Box 81, James Forman Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[27] “Hassan is Ordered to Remove Stickers,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), March 2, 1970.

[28] Fialka, “Black Men Versus the Drug Problem.”

[29] Fialka, “Black Men Versus the Drug Problem”; Earl Byrd, “Hassan: ‘If I go to Prison. . .I Die’” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), December 21, 1973.

[30] Eugene L. Meyer, “Hassan Praised as Drug Informer,” Washington Post, December 20, 1973.

[31] Eugene L. Meyer, “Judge Interfered in D.C. Gun Case,” Washington Post, August 11, 1973.

[32] “Hassan is Ordered to Remove Stickers,” The Evening Star.

[33] “Blackman’s Army Vows Racial War,” Philadelphia Tribune, January 14, 1967.

[34] Paul W. Valentin, “Hassan Turns Drug Program into Black Empire,” Washington Post, April 14, 1971.

[35] William Taaffe, “Black Army Seeks to Clasp Addict’s Hand,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), September 6, 1969

[36] Forman, 35.

[37] John Fialka, “One Doctor Against Heroin and Apathy,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), February 9, 1970.

[38] Timothy Hutchens, “Volunteer Program On Heroin Is Hailed,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), October 22, 1969; William Taaffe “Black Army Seeks to Clasp Addict’s Hand”; Mack, “Trio Fights Dope Use in D.C.”; “Anti-dope Leader Blames Fire on Arson,” Afro-American November, 29, 1969. The four clinics were located at 1403 H Street, NE, 6406 Georgia Avenue, NW (HQ), 14th and V Street, and 14th Street, NW.

[39] Lance Gay, “Aides in Prince Georges Back Black Drug Clinic,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 28, 1970.

[40] Stuart Adams, Dewey F. Meadows, and Charles W. Reynolds, Department of Corrections: Research Report No. 12, February 1969, BoxI:269, Daniel P. Moynihan Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[41] Timothy Hutchens, “Agency on Drug Addition Faces Big Job,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), March 2, 1970.

[42] Jerome Jaffe annotations, David Parker, Memorandum for Egil Krogh and Dr. Jerome Jaffe, from David Parker Re: Address by President before 76 annual Convention of the National Medical Association, July 28, 1971, Box 26, Jerome Jaffe Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[43] Lance Gay, “Young White Addicts Turn to Ghetto for Aid,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), March 16, 1970.

[44] Fialka, “Black Men Versus the Drug Problem.”

[45] Hutchens, “Agency on Drug Addition Faces Big Job.”

[46] Blackman’s Development Center, “Drug Cure: The Humane Alternative to Blanket Methadone Maintenance,” Box 81, James Forman Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[47] Blackman’s Development Center, “Drug Cure: The Humane Alternative to Blanket Methadone Maintenance”; Joe Mack Jr. “Trio Fights Dope Use in D.C.”

[48] Paul Delany, “Militant Urges Ghetto Plan to Include Whites,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), December 21, 1969.

[49] “Anti-Drug Traffic Will Be Presented,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), August 7, 1970; Martin Well, “Unity is Urged at Rally in War Against Narcotics: A Youth’s Message,” Washington Post, August 7, 1970; Kenneth Walker, “Judge Lauds Efforts of Drug Center,” Washington Post, August 10, 1970.

[50] Mack, “Trio Fights Dope Use in D.C.”; Gay, “Young White Addicts Turn to Ghetto for Aid.”

[51] Joan Hanauer, “Girl Scouts Join in War on Drug Abuse,” Baltimore Afro-American, May 13, 1971; “Still Donation to Drug Fight,” Washington Post, August 18, 1971.

[52] Timothy Hutchens, “City Opens Anti-Drug Push,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), September 2, 1970; “Activities of Blackman’s Development Center,” Department of Health Education and Welfare, Department of Labor, and District of Columbia Government, Comptroller General of the United States, April 28, 1972, United States General Accounting Office, 7-8.

[53] “Activities of Blackman’s Development Center” report, Office of the Comptroller, 7, 19-20.

[54] “Activities of Blackman’s Development Center” report, Office of the Comptroller, 7, 20, 12-13.

[55] “Colonel Hassan and Anti-Semitism,” Washington Post, August 8, 1971; Robert N. Giaimo (D-Connecticut) to Elmer B. Staats (Comptroller General U.S.), letter, June 17, 1971; Duncan Spencer, “Hassan Accused of Anti-Semitism, Fund Cutoff Asked,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), April 21, 1971; “Hassan Sues Rep. Giaimo Claims Libel,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), June 22, 1971.

[56] Jeff Donfeld, memorandum for Bud Krogh, Re: Blackman’s Development Center, October 16, 1971, 1-3, Box 26, Jerome Jaffe Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress; “Activities of Blackman’s Development Center” report, Office of the Comptroller, 17.

[57] “Hassan Fund Bid Rejected by HEW,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), July 1, 1971 ; Alma Robinson, “Hassan Quits Center,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), October 8, 1971; “Hassan Seeks Delegate Seat as Republican,” The Evening Star (Washington, DC), January 20, 1972.

[58] Robert L. DuPont and Mark H. Greene, “The Dynamics of a Heroin Addiction Epidemic,” Science 181, August 24, 1973, 721-722.