This is the first post in our Metropolis of the Month for November 2023: Washington, DC, in the Twentieth Century.

“If any city in the United States has borne the burden of serving as a symbol of American aspirations and has simultaneously been the place. . .where the issues of civilization have been focused, it has been the nation’s capital,” wrote historian Howard Gillette Jr. in his 1995 work Between Justice and Beauty: Race, Planning, and the Failure of Urban Policy in Washington, DC.[1] The city exists as an extension of the nation, laboratory for urban policy, and in moments, the culmination of the nation’s hopes, dreams, and sometimes, disappointments.

One year earlier and nearly thirty years ago, journalists Harry Jaffe and Tom Sherwood published Dream City: Race, Power, and the Decline of Washington, DC, a skeptical appraisal of the city under Marion Barry. Early on in the book, the two journalists describe a 1964 voter registration drive appearance by famed Harlem congressional representative Adam Clayton Powell that serves as an example of this sort of skeptical lens. Powell often drew large crowds in New York and expected to do so at All Souls Church, a landmark institution in Washington. After pacing around in the church’s small study, Powell emerged to a small crowd and expressed his dismay. “I have never seen a city in the United States as apathetic as this one,” he lectured the audience. “This is our first chance to be political men and women. We are colonials here in this District. The District of Columbia is the Canal Zone of the United States.”[2] Both works reflect the kind of pessimism that afflicted the nation’s capital by 1995, though if Powell’s episode is indicative at all, possibly stretched back decades.

Gillette argued that despite outbursts of social justice reform such as Reconstruction, the New Deal, and the Great Society, the tension between ensuring justice for Washington’s residents and creating an aesthetically attractive metropolis resulted in policy that nearly always favored the latter. For example, as Reconstruction faded and Democrats reasserted their political power in the capital, “only the most naïve would have failed to recognize that the emphasis of Washington government had shifted from liberty to bricks and mortar.” And, as demonstrated with the end of Reconstruction, even “what one set of leaders achieved in the name of social justice was often undone by those who followed.”[3]

To be fair, by the mid-1990s skepticism about the capital’s state was warranted. Residents had witnessed a series of crises, “the relentless violence, the crumbling schools, the inept public services, the congressional take-over of the city government,” much of which “had generated a desperate desire for good governance,” observe Chris Myers Asch and Derek Musgrove in their 2017 history of DC, Chocolate City.[4] The decades following Gillette, Jaffe, and Sherwood’s work ushered in a very different city, one defined, at least up until recently, more by gentrification and demographic change than crime or public debt. Though the capital stands in much better stead financially in the twenty-first century when compared with 1995, new works have sought to explore more deeply the city’s influence on urban renewal, economic development, policing, and the carceral state with greater emphasis on how Black Washingtonians have fought for increased democracy through these avenues.

Though its unique form of governance had limited the number of histories written about the city, the past thirty years have seen a new focus on the capital not only due to its redevelopment over the same period, which regardless of governance mirrors that of other metropolises across the United States, but also because it often finds itself in the crosshairs of political discourse for serving as a site of or national intersection for debates regarding larger issues. “Washington, DC, a city that served as a bellwether for national policy and political shifts, also presaged local municipal policy and politics during the 1960s and 1970s,” argues historian Lauren Pearlman.[5]

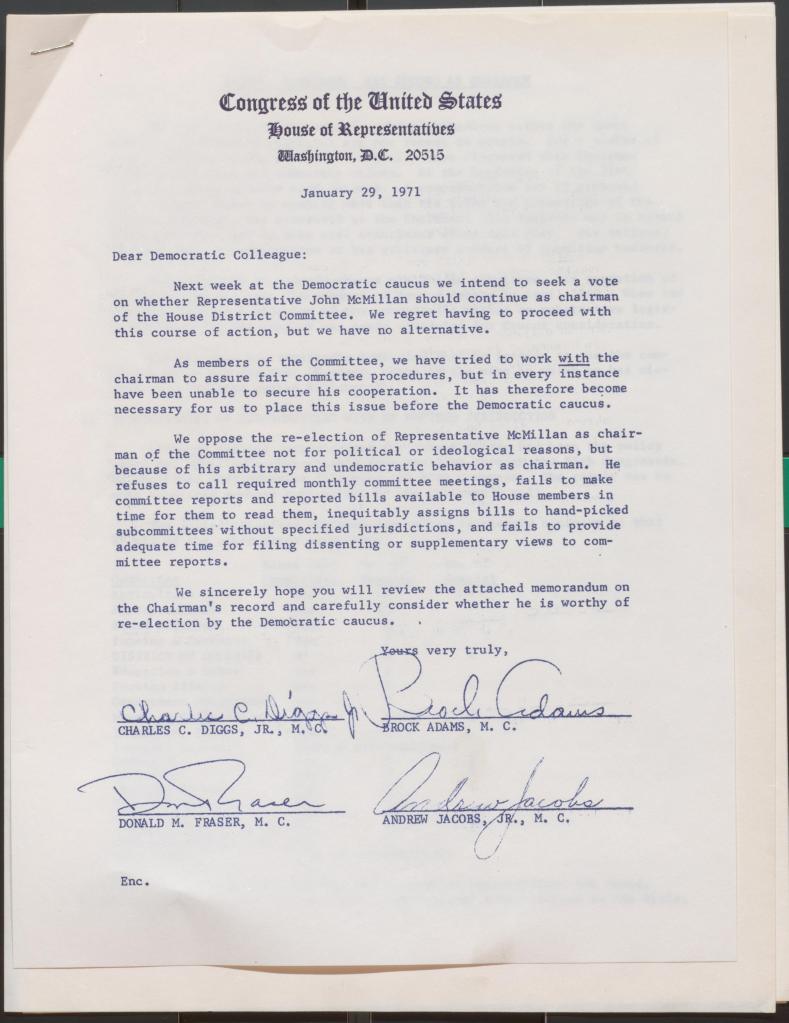

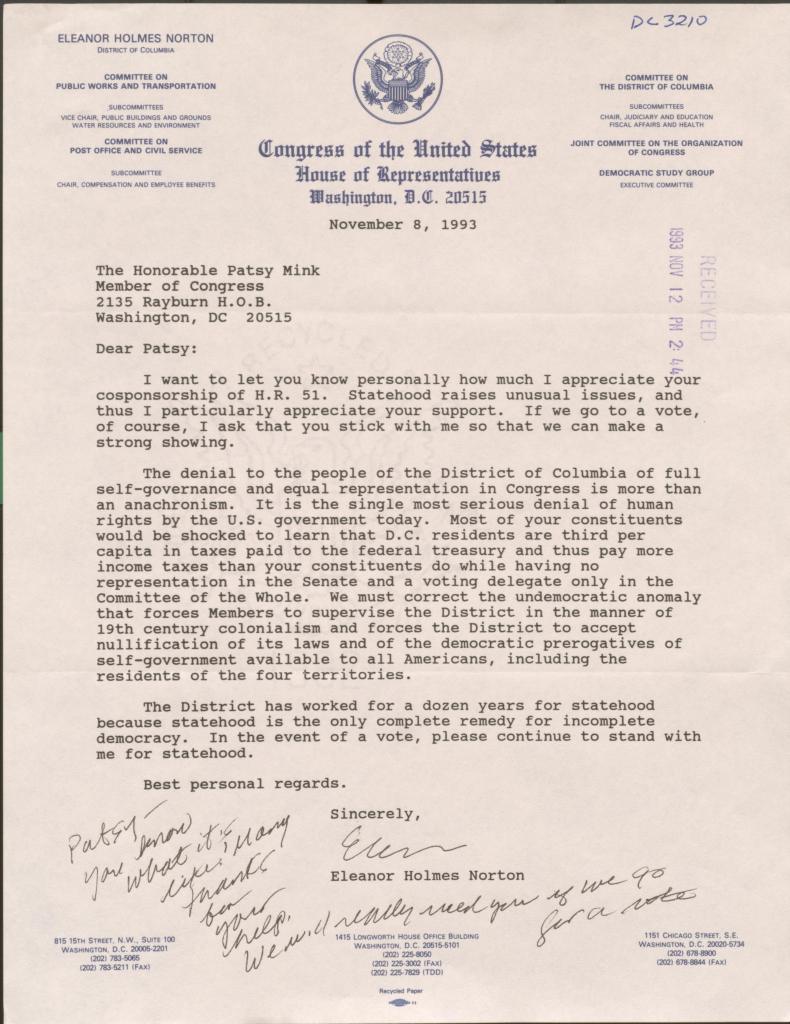

Many of the new works about DC, such as those by Musgrove and Asch, Pearlman, James Forman Jr., and Kyla Sommers, explore the city’s history as it relates to democratic movements within the nation’s capital to achieve equal rights, reform the carceral state, and the experiences of and responses to the 1968 uprising (and its parallels to the Back Lives Matter protests of 2022). While, admittedly, DC’s governance remains sui generis (Home Rule passed in 1973 and was enacted a year later, yet Congress still exerts control over city legislation) it’s also been used as a laboratory for various political experiments, particularly in regard to policing.

The DC Crime Bills of the late 1960s and early 1970s established “reforms” that were replicated widely across the United States. The District of Columbia Reorganization Act of 1970, often referred to as the DC Crime Bill of 1970, “pioneered” policing practices such as preventative detention, increased powers of surveillance, legalization of no-knock warrants, and mandatory minimums. Local DC civil rights activist, religious leader, and the District’s first congressional delegate to Congress Walter Fauntroy described the bill at the time as “the cutting edge of fascism and oppression in the United States.”[6] Judging from the nation’s prison system and policing practices, Fauntroy was not too far off, a point to return to in a moment.

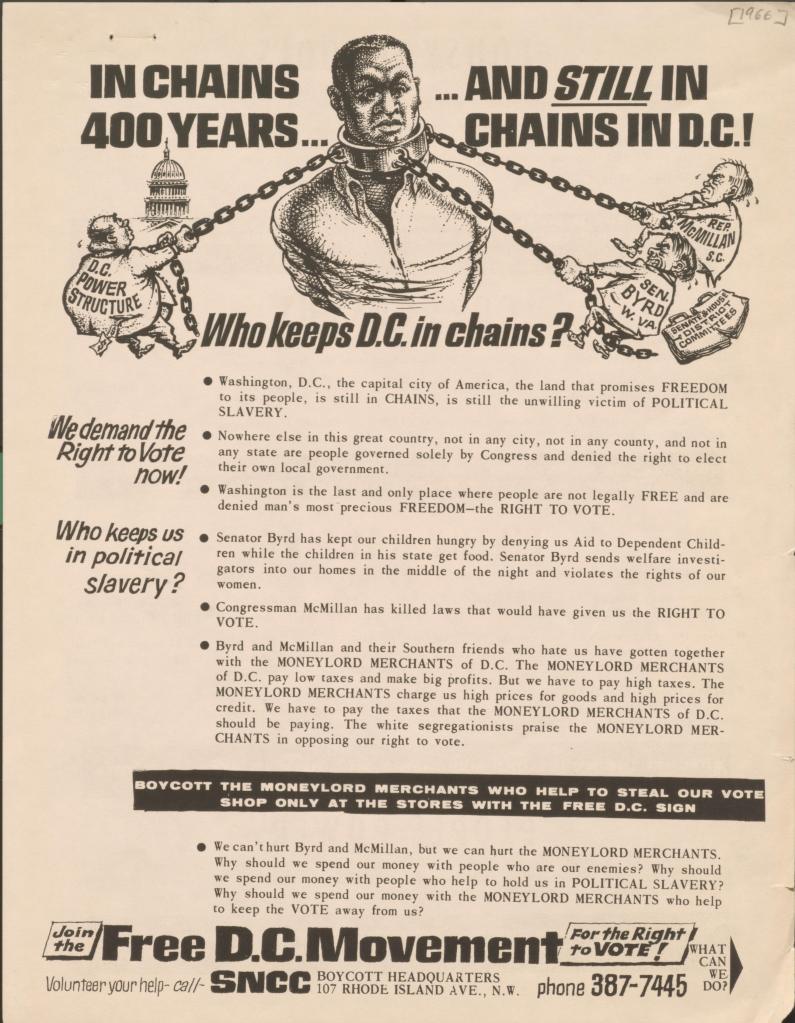

If any event raised national concern regarding the capital, the 1968 uprisings might be the dominant example, particulalry seen from the viewpoint of white and, to a lesser extent, Black elites. In her 2023 book When the Smoke Cleared, historian Kyla Sommers explores the 1968 unrest from the vantage point of Black Washingtonians, harnessing a vast archive of oral histories that trace their experiences from the uprising to the aftermath, thereby highlighting the “political aspects of the disturbances and connect[ing] these events to the demands of prior activism” and shifting the framing of 1968 as less about death and destruction and more about Black DC targeting “manifestations of the ‘power structure’ as they demanded freedom, economic opportunities, good education, accountable policing, voting rights and political power for over a century.”[7]

Indeed, the focus on grassroots Black activism, from moderates to radicals, has been a subject excavated by Sommers, Lauren Pearlman, Asch and Musgrove, and Gillette, though in comparison Gillette spends less time on the late twentieth century than his four counterparts. Additionally, Asch and Musgrove expand their book to encompass the city’s entire history rather than just the second half of the twentieth century, though its focus is on the effort of Black Washington to gain greater political rights in the city.

Sommers, Asch, Musgrove and Pearlman offer what some might suggest are correctives to the Jaffe-Sherwood history, which functions in large part as a biography of the city’s most powerful politician, Marion Barry, and arguably underplays the grassroots democratic movements wherein Barry sometimes played a role. For example, Sommers delves into the Black United Front (BUF), a coalition of moderates like Fauntroy and militant Black DC leaders, such as Stokely Carmichael, pushing for community action reforms and development in the aftermath of the 1968 unrest.

Sommers builds on Gillette’s work in this regard. Gillette also explored the efforts of the BUF, though his focus was more directly on Fauntroy’s Model Inner City Community Development Organization (MICCO), a coalition of 150 community organizations, churches, and civic groups looking to rebuild the historically Black Shaw neighborhood through local actors and leaders rather than white corporate developers.[8] Fauntroy and others hoped to avoid the calamity that was the Southwest Urban Renewal project of the mid-1950s, which ultimately caused widespread displacement for Black families. Fauntroy even refused to use the term urban renewal, lamenting that the Southwest project failed to provide new housing for those displaced in the new development or help with relocation. The bitterness of the project remained “etched in the memory of many residents in the area.”[9]

For a period, MICCO and other local organizations “encouraged Washingtonians to claim their share of public resources,” observe Asch and Musgrove. However, by the late 1960s and early 1970s, despite some successes, white business leaders clawed back their power and influence.[10] “The era when neighborhood-based Black organizations could direct and not just influence the reconstruction of their own communities had clearly passed,” wrote Gillette.[11] As Sommers points out, this shift failed to result in quicker results, but when the real estate boom and neoliberalism delivered greater economic prosperity in the late 1990s and 2000s, the media portrayed it as the work of private industry and developers, ignoring the contributions of civic actors like the BUF and others.[12]

Black activism serves as the focus of Pearlman’s 2019 work, Democracy’s Capital: Black Political Power in Washington, DC, 1960s-1970s. While Fauntroy is one of the critical figures in Pearlman’s work, she expands her focus to more militant actors, such as irrepressible Julius Hobson, the BUF, and Douglas Moore. Pearlman digs into the tension between LBJ’s Great Society federal programs, meant to alleviate poverty and address racial inequality, and greater democratic rights pressed for by the city’s predominantly Black residents. A conflict that she argues fractured “Black Washington and because white stakeholders and Black leaders vied for power in the absence of elected representation, urban renewal, much like anticrime measures, remained a contentious issue in the public sphere.”[13]

Returning to the issue of the city’s carceral state, Pearlman explores the run-up to the passage of Home Rule in 1973 and the ways in which the discourse about crime, and law and order rhetoric from LBJ through Nixon, undermined the policies meant to address such issues.[14] In a callback to Gillette’s focus on urban renewal, Pearlman delves into the Pennsylvania Avenue Redevelopment project led by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a process that, much like what occurred in Shaw, ultimately sidelined local government and municipal officials. “Everyone knew the plans were intended to enhance a short but symbolically charged, parade route—not to make a symbolic tie between diverse parts of the city by fixing up the whole avenue,” observed one local architect at the time.[15] Building on Gillette’s work, Sommers and Pearlman agree that too many scholars have ignored the impact of Black Power politics beyond crime and drug policies.

In a metropolis known as Chocolate City and with this increased focus on the agency of Black Washingtonians, in his Pulitzer Prize–winning Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America (2016) James Forman Jr. privileges local activism, but includes the agency of the city’s more conservative Black leaders, or at least conservative in terms of responses to crime. According to Forman, the crises of the 1970s, notably the heroin epidemic that plagued DC from the mid-1960s into the early portion of the following decade, led many leaders to disavow marijuana legalization efforts and advocate for more “tough on crime” solutions generally, thereby choosing more punitive solutions. Even Fauntroy pushed for mandatory minimums for those found selling firearms illegally in DC.

Douglas Moore provides a useful example. A city council member and a member of the BUF, Moore wore dashikis and black leather coats, hardly the sartorial choices of conservatives, yet he rejected marijuana legalization, arguing that Black men and women, due in large part to systematic racism, could not afford to abuse drugs. “In his eyes, marijuana use was both a symptom of racial oppression—blacks who used the drug were ‘suffering from the stresses of white racism’—and, just as important, a cause. Drug users, Moore believed, were in no position to undertake the work of rebuilding their individual lives, let along that of collectively mobilizing against racism,” writes Forman.[16] Moreover, as Forman demonstrates, many Black leaders advocated for more African American police as a solution to the long-simmering issue of police brutality.[17] These leaders also made sure that Black victims of crime were heard. After all, for all the talk of law and order by white politicians like Richard Nixon, Black residents were most subject to crime. In 1975, 85 percent of those killed by guns were Black.[18]

Though driven by race-conscious grassroots political activism, the reforms they adopted (or in the case of legalization rejected) helped to construct the carceral state that has imprisoned so many Black Americans. The introduction of crack into the urban scene during the 1980s served as a vicious accelerant regarding these issues. DC’s first Black United States Attorney and future Obama attorney general Eric Holder openly instituted pretext traffic stops, which gave the police more authority to conduct searchers but also violated the civil liberties of residents, especially Black Washingtonians, a fact Holder openly acknowledged when he told one predominantly Black audience, “I’m not going to be naïve about it. . .The people who will be stopped will be young black males, overwhelmingly.”[19]

From the late 1990s to today, Washingtonians witnessed an economic boom that reshaped the city, beneficial to some, less so to others. The historically Black U Street corridor was transformed, but not for everyone. “Cultural landscapes are always changing and so it is, too, with U Street,” reflected journalist Natalie Hopkinson in 2012. “By 2005, the view of Fourteenth and U Streets depended on how long you had been looking at it.”[20]

Black homeownership rates in the city fell as white ones rose; gentrification forced many Black renters to leave as white ones replaced them. The title of Hopkinson’s book, Go-Go Live: The Musical Life and Death of a Chocolate City, conveys her general opinion that whatever DC is today, it’s not what it was. During the new century, mayors adopted a technocratic approach that drew on academia, think tanks, and non-profit organizations and Congress for appointments; a professional universe “whiter than a Sarah Palin rally” that made its way into city government. Working-class Blacks also felt the squeeze from a growing Latino population.

To be fair, whatever its faults, the city’s finances and politics stand in better shape now than in 1995, when a financial control board assumed control of the city, more or less ending Home Rule for a period. Home Rule returned with the ascension of Anthony Williams Jr. as mayor in 1999. His business-friendly policies were viewed by Congress as reason enough to return most of DC’s self-governance and coincided with, and perhaps helped to facilitate, the real estate boom of the early aughts that wiped away the city’s debt and reshaped it into a gleaming neoliberal citadel.

If Washington became Chocolate City in 1957, it became what one Washington Post writer labeled Latte City in 2015, as Black residents left the city and white ones replaced them. Hopkinson ties this demographic change in the capital to a central irony—it stemmed from what many would call positive developments regarding race. “Now, the Chocolate City is dying. That it gave way to Mr. Obama’s Washington is no coincidence; it’s poetic justice,” she argues. The white children of those that had fled a generation earlier had released “their fears” of the metropolis and this same conviction enabled them “in the quiet sanctity of the voting booth, to vote for a [B]lack man.”[21]

While Hopkinson explores DC in regard to its intersection with the history of GoGo, a musical genre unique to Black Washington, which developed alongside Home Rule, she describes how even if the capital’s newer white residents bring with them more enlightened views about race, their affluence causes gentrification, and for many local residents their behavior is exclusionary. Dorothy Brazil, a longtime DC resident who oversaw the government watchdog organization DCWatch for decades, confided to Hopkinson her frustrations with white newcomers to her Columbia Heights neighborhood in 2010: “They don’t speak. And if you’ve been here for more than ten years, then you are part of the problem.” The rhetoric of crime outlined by Sommers, Pearlman, and Forman from the late 1960s and 1970s pushed forward into the twenty-first century. Hopkinson argues the notion of “black on black crime” had been “used as a weapon to encourage public policies that treat Black people as blights on the new urban aesthetic.”[22]

“In DC gentrification often feels like the front line of a war zone,” writes Carolyn Gallaher. “The war is fought with words, but it is no less intense.” Words and occasionally, as Gallaher explores, legislation. The passage of the Tenant Opportunity to Purchase Act (TOPA) in 1980 by the city council, for example, sought to protect the city’s affordable housing stock. It also aimed to reduce displacement by enabling tenants’ associations to purchase a property and then allow tenants to buy their existing units. This serves as one example of how the city’s leaders tried to address the impact of gentrification.

Unfortunately, as Gallaher notes in her 2016 book focusing on TOPA and condo conversions in the city, TOPA has helped some folks buy their residences, but it has not been able to reduce gentrification around their homes. Moreover, according to Gallagher, TOPA actually facilitated exclusionary displacement through some of its practices, such as the use of voluntary agreements and buyouts. Nor did TOPA appear to be the kind of law that would “serve as springboard for [a] future more durable resistance,” yet at the same time, Gallaher acknowledges that while not radical itself, it inspires moments that feel radical and pregnant with possibility, which serves as a starting point, at least, “for wider political empowerment and not just individual tenants but collectives of them.”[23] Gallaher is among a cadre of urbanists, including Derek Hyra, Sabiyha Prince, Gabriella Gahlia Modan, and Brett Williams, who have devoted great attention to this issue in recent years.

For the twentieth anniversary of Dream City, Jaffe and Sherwood added an afterword covering the ensuing two decades since publication: “Race, Money, Corruption, and the Revival of Washington, DC.” The title reflected equal parts pessimism and hope, yet the two journalists acknowledged that by 2010 revival along Fourteenth Street was evident, but it had not lifted all boats. The transformation of the Central Union Mission proved emblematic of the city’s twenty-first century growth. A shelter for the homeless for decades, the mission had been converted into new housing largely for the “young, white, and wealthy.” White newcomers and others brought new affluence and energy to the city, but for its poorer residents, “unemployment, poor health, and violent crime” continued to plague their communities, especially in areas east of the Anacostia River.[24]

DC might be the superstar city several panelists at the 2019 Society for American Regional and Planning History (SACRPH) conference described it as, but that star’s shine fails to reach everyone. Perhaps in the coming decades, DC will become more like the ideal upon which it was constructed, rather than the pessimistic reality it seems unable to escape.

For this month’s bibliography we focused on works exploring the city’s twentieth-century history. As always, the bibliography is just a starting point; we encourage others to place additional titles in the comments below.

Bibliography

Asch, Chris Myers and George Derek Musgrove. Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Austin, Paula. Coming of Age in Jim Crow D.C. Navigating the Politics of Everyday Life. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

Cervini, Eric. The Deviant’s War: The Homosexual vs. The United States of America. New York: Farrar, Strausss, and Giroux, 2020.

Forman, James, Jr. Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2017.

Gallaher, Carolyn. The Politics of Staying Put: Condo Conversion and Tenant Right-to-Buy in Washington, DC. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2016.

Gillette, Howard, Jr. Between Justice and Beauty: Race, Planning, and the Failure of Urban Policy in Washington, DC. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994.

Hopkinson, Natalie. Go-Go Live: The Musical Life and Death of Chocolate City. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012.

Hyra, Derek. Race, Class, and Politics in Cappuccino City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Hyra, Derek, and Sabiyha Prince, eds. Capital Dilemma: Growth and Inequality in Washington, DC. New York: Rutledge, 2016.

Jaffe, Harry, and Tom Sherwood. Dream City: Race, Power, and the Decline of Washington, DC. Washington, DC: Argo Navis Author Services, 2014.

Johnson, David K. The Lavendar Scare: The Cold War Persecution of Gays and Lesbians by the Federal Government. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Kirchick, James. Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington. New York: Holt Paperbacks, 2023.

Logan, Cameron. Histroric Capital: Preservation, Race, and Real Estate in Washington, DC. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Lornell, Kip and Charles C. Stephenson Jr. The Beat: Go-Go Music from Washington, DC. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009.

Lloyd, James M. “Fighting Redlining and Gentrification in Washington, DC: The Adams Morgan Organization and Tenant Right to Purchase,” Journal of Urban History 42, no. 6: 1091-1109, https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144214566975.

Modan, Gabriella Gahlia. Turf Wars: Discourse, Diversity, and the Politics of Place. New York: Wiley-Blackwell, 2007.

Murphy, Mary-Elizabeth. Jim Crow Capital: Women and the Black Freedom Struggle in Washington, DC, 1925-1945. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

Musgrove, G. Derek. “’Statehood is Far More Difficult’: The Struggle for D.C. Self-Determination, 1980-2017,” Washington History 29, no. 2 (Fall 2017): 3-17.

Pearlman, Lauren. Democracy’s Capital: Black Power in Washington, DC, 1960s-1970s. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Prince, Sabihya. African Americans and Gentrification in Washington, DC: Race, Class, and Social Justice in the Nation’s Capital. New York: Rutledge, 2014.

Ruble, Blair A. Washington’s U Street: A Biography. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 2012.

Schrag, Zachary M. The Great Society Subway: A History of the Washington Metro. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 2014.

Sommers, Kyla. When the Smoke Cleared: The 1968 Rebellions and the Unfinished Battle for Civil Rights in the Nation’s Capital. New York: The New Press, 2023.

Thomas, Briana A. Black Broadway in Washington, DC. Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2021.

Summers, Brandi Thompson. Black in Place: The Spatial Aesthetics of Race in a Post-Chocolate City. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Williams, Brett. Upscaling Downtown: Stalled Gentrification in Washington, DC. New York: Cornell University Press, 1988.

Featured image (at top): Aerial view of the Lincoln Memorial looking towards the Washington Monument, (March 29, 1958). Thomas J. O’Halloran, photographer, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

[1] Howard Gillette Jr., Between Justice and Beauty: Race, Planning, and the Failure of Urban Policy in Washington, DC (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1994), 208.

[2] Harry Jaffe and Tom Sherwood, Dream City: Race, Power, and the Decline of Washington, DC (Washington, DC: Argo Navis Author Services, 2014), 14-15.

[3] Gillette, Between Justice and Beauty, 61, x.

[4] Chris Myers Asch and George Derek Musgrove, Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 435.

[5] Lauren Pearlman, Democracy’s Capital: Black Power in Washington, DC, 1960s-1970s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019), 6-7.

[6] Kyla Sommers, When the Smoke Cleared: The 1968 Rebellions and the Unfinished Battle for Civil Rights in the Nation’s Capital (New York: The New Press, 2023), 186-187.

[7] Sommers, When the Smoke Cleared, 195.

[8] Gillette, Between Justice and Beauty, 174.

[9] Gillette, Between Justice and Beauty, 174-175.

[10] Asch and Musgrove, Chocolate City, 350.

[11] Gillette, Between Justice and Beauty, 188.

[12] Sommers, When the Smoke Cleared, 192.

[13] Pearlman, Democracy’s Capital, 200.

[14] Pearlman, Democracy’s Capital, 4-5

[15] Pearlman, Democracy’s Capital, 207.

[16] James Forman Jr., Locking Up Our Own: Crime and Punishment in Black America (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2017), 34-37.

[17] Forman, Locking Up Our Own, 82-84.

[18] Forman, Locking Up Our Own, 56-57.

[19] Forman, Locking Up Our Own, 197-200, 203

[20] Natalie Hopkinson, Go-Go Live: The Musical Life and Death of Chocolate City (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012), 25.

[21] Hopkinson, Go-Go Live, 7, 148.

[22] Hopkinson, Go-Go Live, 156-157.

[23] Carolyn Gallaher, The Politics of Staying Put: Condo Conversion and Tenant Right-to-Buy in Washington, DC (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2016) 67, 120-157, 218, 229.

[24] Jaffe and Sherwood, Dream City, 434.

Readers of this essay may find of use the chapter on Washington in my 2022 book, The Paradox of Urban Revitalization, “In Chocolate City, A Fight to Hold On.”

LikeLike