The seventh entry in this year’s Graduate Student Blogging Contest is by Bridget Laramie Kelly, who won last year’s blogging contest. In this year’s entry, she writes about how a historic Black suburb was perceived by wealthier white residents as a “stumbling block” in the way of protecting and increasing property values. To see all entries from this year’s contest check out our round up here

I grew up in Kirkwood, Missouri, the first planned commuter suburb built west of the Mississippi River. Originally established as a railroad town west of St. Louis City, today the independent city possesses some of western St. Louis County’s most desirable real estate. My memories of Meacham Park, the Black neighborhood on Kirkwood’s edge, are just that: peripheral.

Locals remember this history as one of inevitable progress, logical development, and Christian charity: a wealthier, white neighborhood annexed a poorer, Black neighborhood and they became “one,” which then extended well-funded public works and services to the lower-income neighborhood. Not only is this account self-serving, but it is also incorrect.[1] Kirkwood and St. Louis County manufactured blight as a pretext for their long-established plans to capture Meacham Park and quite literally turn Black homes into HomeGoods. This is the story of two adjacent neighborhoods and their conflict over annexation, which at its very core is a conflict over belonging.

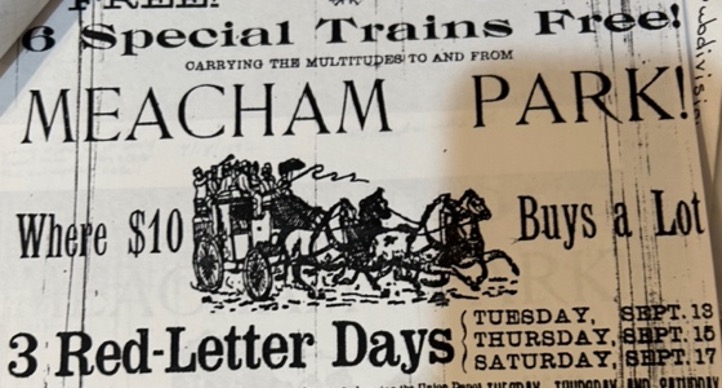

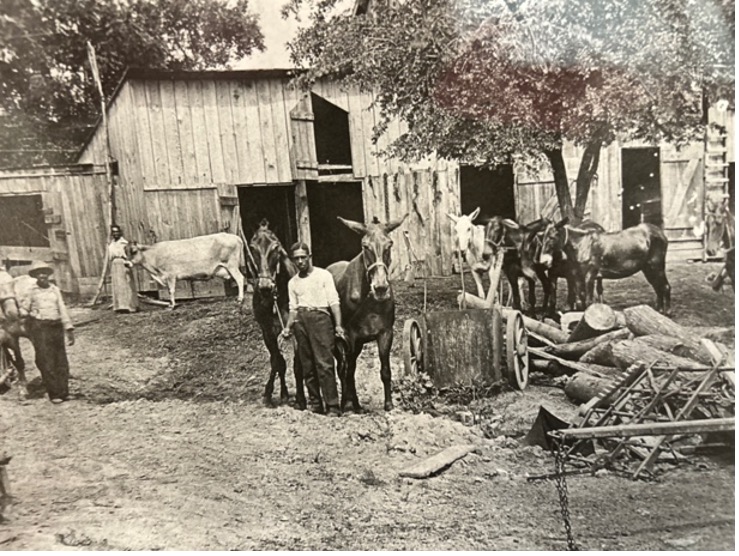

Founded in 1890, Meacham Park was one of the first suburban neighborhoods settled by Black Americans. Real estate developer Elzey Eugene Meacham sold ten-dollar parcels of undeveloped land, quickly transforming the Missouri marsh into an affordable, inner-ring Black suburb.[2]

While most Black migrants from the rural South relocated to industrial cities during the Great Migration, a significant number of migrants found and built community in suburban networks such as Meacham Park.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, the historic Black suburb represented the only area in St. Louis County where Black people could purchase homes and build businesses. Gertrude Johnson, lifelong resident of Meacham Park, described twentieth-century life in the neighborhood as “self-sufficient,” but the Great Depression hit isolated Black neighborhoods especially hard.[3] Yet incredibly, Bill’s Barber Shop, Moses’ Pool Hall, and other local, Black-owned businesses survived and remained neighborhood anchors.[4]

Meacham Park represented a place where Black Americans could establish businesses and build equity, but due to the nature of racial segregation and discrimination, municipal services in Meacham Park operated with far less funding, oversight, and predictability, compared to the wealthier, white neighborhood of Kirkwood. Meacham Park residents shared a border with Kirkwood but did not share access to its fully funded municipal services, and in 1966 five Black children tragically died in a house fire because their volunteer fire department’s engine failed to start.

Meacham Park’s experience demonstrates how suburbs have long been racially contested spaces. In a 1967 article titled, “A Shock for Suburbia,” the St. Louis Post-Dispatch identified the suburban problem in explicitly racial terms: “Upward mobility is not for nice people only…The gangsters and the hoodlums also joined the exodus to the suburbs.”[5] This St. Louis columnist defined the suburban dream as the right to exclude Black Americans; “blight” came to represent Black, and became the neoliberal tool for material dispossession. The Post-Dispatch continued building the case against Meacham Park’s “blight,” and in another article editorialized that the county council “has an opportunity to serve the wide community interest in eliminating pockets of blight” and described Meacham Park as a “special case,” one that warranted unprecedented local and federal investment due to the neighborhood’s proximity to an upper-middle-class, white suburb, unlike the more isolated Black neighborhoods in North County.

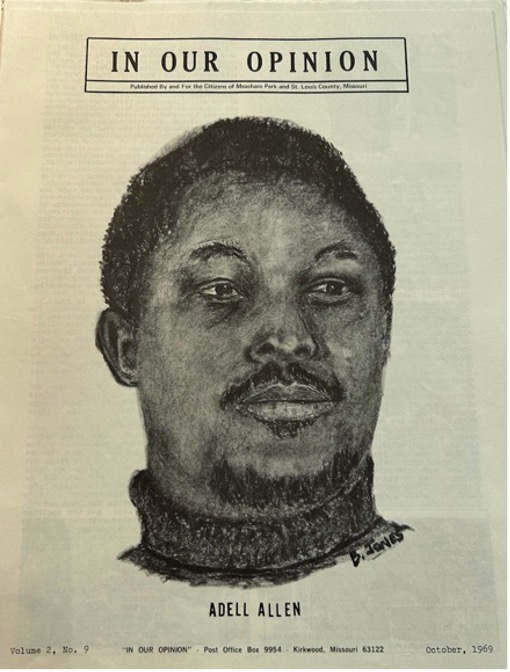

Meacham Park published a magazine called In Our Opinion, which featured local news and included stories and poems written by community members. The October 1969 issue featured Adell Allen, a Black engineer employed at McDonnell Aircraft Company (now Boeing). Allen moved to Meacham Park because Kirkwood and every other municipality in the county excluded Black people from the suburban real estate market. Allen channeled his frustration with the “Gateway to the West’s” racial geography into political activism, and in 1970 brought his concerns to the nation’s capital. Allen testified before the Civil Rights Commission: “You can tell you are in our area by the inadequate lighting…We have to have chain phone calls to get the things that already belong to us.”[6] Meacham Park residents fought hard for basic services that Kirkwood residents never had to imagine living without, such as sidewalks, fire protection, and a functional sewage system. Two years after Allen’s testimony, Commerce Bank and Kirkwood’s First Presbyterian Church established a Homeowners Assistance Plan designed for Meacham Park residents. Under this Anglo-Christian banking initiative, if Black homeowners met certain financial requirements, they could qualify for a sewer installation loan “at a very reasonable rate of interest.”[7]

St. Louis County Supervisor Lawrence K. Roos led the “anti-blight” campaign and targeted Meacham Park for the pilot program, promising that “suburban renewal would be urban renewal’s opposite.”[8] Roos wanted West County suburbs to believe that unless they acted soon, “the County would eventually go the way of the City of St. Louis.”[9] The St. Louis campaign against suburban “blight” was successful; in the early 1970s, eleven unincorporated suburbs received the diagnosis of “blight,” which loosened property laws and financing under eminent domain.

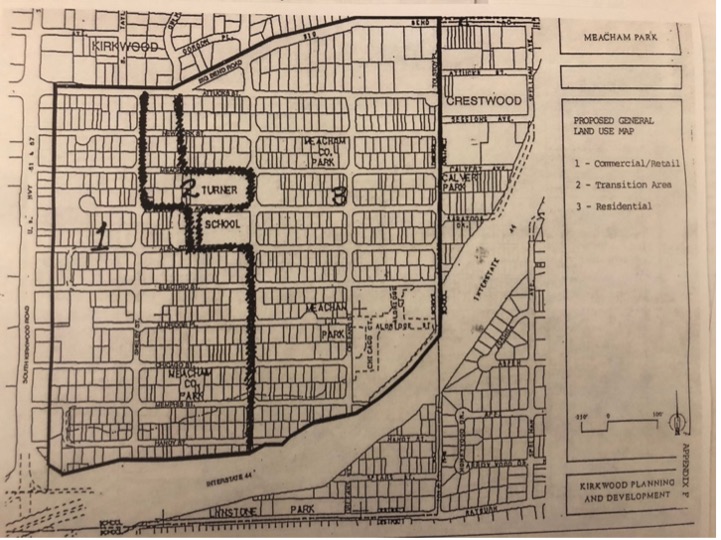

Disguised as racial integration into the fully funded subdivision of Kirkwood, the ordinance to annex Meacham Park into Kirkwood passed overwhelmingly in 1991. The promise that annexation would produce improved city services concealed the actual, but hidden, price tag for community membership, made conditional by the demolition of hundreds of Black businesses and homes.

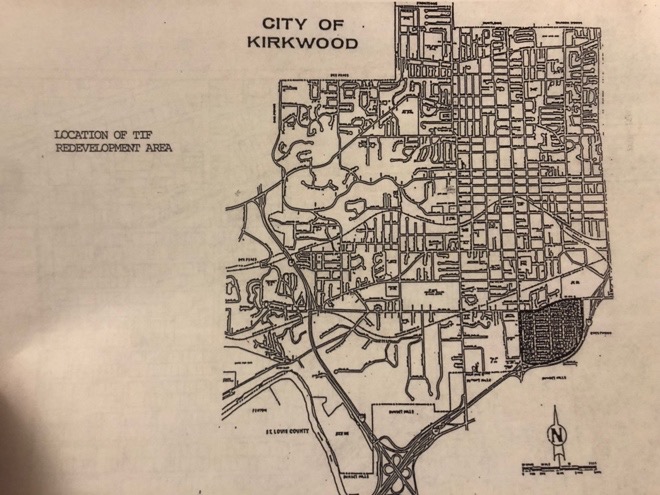

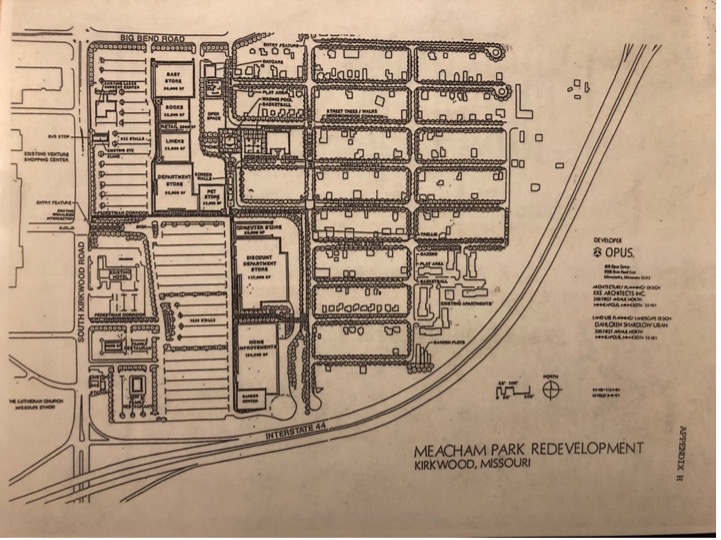

Just three years after annexation, Kirkwood City Council approved a redevelopment plan to build a large-scale shopping center called Kirkwood Commons. It was part of the Meacham Park Redevelopment Project approved on December 1, 1994, and fit into the national trend of neoliberal commercial development with public funds, since the project technically covered “blight.”[10]

Conditional financing is an important element to this story. Prior to annexation Meacham Park families had to meet demonstrable standards in order to qualify for a sewage installation loan, money they eventually had to pay back at high interest rates. Tax Increment Financing (TIF), on the other hand, allows a private developer to receive public money without the expectation of future reimbursement.[11] In this case, taxpayers paid DESCO seventeen million dollars to build Walmart, Target, and other big-box stores. The residents of Meacham Park had to meet specific financial requirements for a public good like sewage systems, whereas DESCO developers only had to declare “financial unfeasibility in the market” to secure millions in taxpayer funds for the private development of Kirkwood Commons.[12] The onslaught of TIF incentives in Missouri and elsewhere unleashed a devastating decline in public and predominantly Black spaces.

Developers promised that Meacham Park would experience a “transformation” with a full range of public amenities while “still preserving the social fabric of the neighborhood,” but that was not the case.[13] Mayor Herb Jones admitted the footprint of the commercial development doubled its original limits, although he rationalized miscalculations were to be expected in large-scale development.[14] In 1997 DESCO developers revoked the mutually agreed upon Shelby boundary, which would have preserved a majority of Black homes and businesses, which Harriet Patton, president of the Meacham Park Post Annexation Association, had warned would happen.[15] As a result, bulldozers demolished over one third of Meacham Park’s original 135 acres.

All but one of the original homes in the historic, predominantly Black community are gone; so are churches and Bill’s Barbershop.[16] Nearly 80 percent of the two hundred people who lived in the western part of Meacham Park have left the neighborhood. Kirkwood officials defended this form of annihilation, because in their view, they had to destroy part of Meacham Park to save the rest. They even referred to the displacement process as “radical surgery,” whereas many Meacham Park residents referred to the move as a “double-cross,” that in Meacham Park resident Pat Martin’s view paid “homage to the almighty dollar.”[17] Eugene Jones, pastor of the Douglas Memorial Church warned, “history will be lost,” as he looked upon the “dust rising from the construction site” that once was home to some of America’s earliest Black suburban pioneers.[18] “They’re making our neighborhood a ghost town,” said Patton in the winter of 1997.[19]

The history between Meacham Park and Kirkwood represents a broader pattern in American suburban development that advances capital gains through the erosion of democratic space and displacement of Black Americans. Kirkwood applauds themselves for passing the annexation measure; current mayor Timothy Griffin often characterizes this history in generous terms and refers to annexation as the natural next step following school integration.[20] This remembrance downplays the very deliberate assessment of the real estate value Meacham Park possessed, which now generates millions of dollars in sales tax revenue to the City of Kirkwood.

The painful reality remains that Kirkwood officials and residents required Meacham Park to relinquish their community’s core, their “social fabric,” to the benefit of Kirkwood’s tax base.[21] Civic goodwill was insufficient in 1966 when five Black children died in a house fire while Kirkwood’s trucks remained idle in their firehouse.[22] Why didn’t incorporation happen then and without the demolition of hundreds of homes?

Mayor Griffin tells a sweet story about school integration and their shared identity as Kirkwood High School Pioneers but obscures the full story. Kirkwood imagined Meacham Park as a “stumbling block,” which, in their view, obstructed their development plans and jeopardized property values. Kirkwood residents believed they could overcome these perceived threats through annexation, redevelopment, and ultimately the razing of a Black neighborhood.

Bridget Laramie Kelly is a fourth-year PhD candidate in International Urban History. Her dissertation, “The Harlem Uprising of 1943: Anti-Colonial Violence & the Formation of Probationary Citizenship,” develops a new framework for understanding the Harlem “riot,” paying special attention to the centrality of women as actors and their central role in the violence. At the same time, it foregrounds the governmental reaction to the uprising and the creation of a new juridical and political category of degraded sub-citizenship, which she calls “probationary citizenship,” based on a pre-trial probationary status for arrested “rioters” who, under the guise of “leniency” and after extensive investigation of their intimate and psychological lives, were “offered” and “accepted” conscription into US military service. The innovation of her project is to analyze these mutually constitutive dynamics together and in relation: the anti-colonial politics of violent popular rebellion and the experimental creation of a new kind of US warfare state based on the Black worker soldier. Before accepting a graduate position as a Chancellor’s Fellow at Washington University-St. Louis, Bridget taught social studies for seven years. Bridget’s broader intellectual interests include urbanization, American Indian studies, and race and gender in the city.

Featured image (at top): Map from “Meacham Park Redevelopment, City of Kirkwood, Missouri, Development Proposal” sent from William J. Baker, Director of National Retail Development at Opus Group of Companies, to Ms. Rosalind Williams with the City of Kirkwood, March 7, 1994. Initially, Opus won the bid to redevelop Meacham Park, but dropped out due to “racial concerns,” and then the local development company, DESCO, took over the project.

[1] For the best scholarship on Meacham Park and Kirkwood see: Colin Gordon, Citizen Brown: Race, Democracy, and Inequality in the St. Louis Suburbs (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017); For historiography on Black suburbs see: Andrew Wiese, Places of Their Own: African American Suburbanization in the Twentieth Century (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005); Mary Pattillo, Black Picket Fences: Privileges & Peril among the Black Middle Class (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1999, 2013); Todd M. Michney, Surrogate Suburbs: Black Upward Mobility and Neighborhood Change in Cleveland, 1900-1980 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

[2] A number of lots were also sold to white people, but by the turn of the century, the subdivision comprised a predominantly Black neighborhood. Mr. Meacham developed a total of seven subdivisions near St. Louis (Meacham Park, West End Park, Elmwood, West Tower Grove, North Cabanne, Malcolm Terrance, Hillsdale). The other six subdivisions represented the typical suburban pattern in its white demographic.

[3] Lonnie R. Speer, “Meacham Park: A History 1892-1989,” (1998), http://www.meachamparknia.org/uploads/2/2/7/9/22798842/mp-history.pdf. Lonnie R. Speer, in collaboration with Meacham Park icons Bill Jones and Garnet Thies, produced a comprehensive overview of Meacham Park. Other historically Black urban neighborhoods in St. Louis City, such as Mill Creek Valley, Carr Square, and the Ville, had no such luck as postwar interstate highway projects evicted residents through eminent domain.

[4] Lonnie R. Speer, “Meacham Park.”

[5] “A Shock for Suburbia,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 1967.

[6] Adell Allen, U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Hearings Held in St. Louis, 304-5.

[7] Lonnie R. Speer, “Meacham Park.”

[8] Full quote: “Unlike projects such as Pruitt-Igoe we didn’t come in in a patronizing way and build a structure that was not suited to the tastes of the people in the community.” Eric L. Zoeckler, “County Campaign on Blight,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 27, 1973.

[9] Eric L. Zoeckler, “County Campaign on Blight”; “Transforming Meacham Park,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 22, 1967.

[10] Craig L. Johnson and Kenneth A. Kriz, Tax Increment Financing and Economic Development: Uses, Structures, and Impact (Albany: SUNY Press, 2019), 126. Full quote: “It is taking money away from important public purposes—such as education and parks—and giving it to private property owners and real estate developers.”

[11] Ferguson was the first Missouri municipality to use Tax Increment Financing (TIF) in connection to redevelopment projects. In Opus’s proposal, the company compared Ferguson’s East Woodstock TIF to the Meacham Park project “in that commercial development generated the funds for needed neighborhood improvements.” In a section titled, “TIF Experience” the Opus team wrote, “The East Woodstock area faced the same challenges arising from distressed housing stock and disinvestment.”

[12] “3-Year Plan to Shed Meacham Park Blight,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 4, 1972.

[ 13] “Meacham Park Redevelopment, City of Kirkwood, Missouri, Development Proposal,” sent from William J. Baker, Director of National Retail Development at Opus Group of Companies, to Ms. Rosalind Williams with the City of Kirkwood, March 7, 1994. Initially, Opus won the bid to redevelop Meacham Park, but dropped out due to “racial concerns,” and then the local development company, DESCO took over the project.

[14] Regina DeLuca, “Commercial to Take More Than Expected,” Kirkwood Historical Society.

[15] Association members opposed redevelopment especially after the violation of the stated boundary, and instead of a shopping center, they wanted “more affordable housing, more small businesses, and more senior citizen housing.” Harriet Patton stated, “We want to see Kirkwood and Meacham Park working together…we ask that Kirkwood go back to the table and start looking seriously to keeping its promise.” DeLuca, “Commercial to Take More Than Expected.”

[16] Under the redevelopment zoning laws, the land occupied by Bill’s Barbershop was rezoned for residential use. “Judge Reverses Ruling Demolishing Barber Shop,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch. March 6, 1998.

[17] 3-Year Plan to Shed Meacham Park Blight,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 4, 1972; DeLuca, “Commercial to Take More Than Expected.”

[18] Lorraine Kee, “Commercial Development Swallows up a Kirkwood Neighborhood.” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 7, 1999.

[19] D.J. Wilson, “Meacham Park Blues,” The Riverfront Times, February 11-17, 1997.

[20] Ethan Peters, “Sectored Off: Meacham Park,” The Kirkwood Call, June 9, 2020.

[21] “Meacham Park Redevelopment, City of Kirkwood, Missouri, Development Proposal.”

[22] Jaclyn Brenning, “Kirkwood’s Journey: Separating Myths and Realities about Meacham Park, Thornton, Part 2,” STL Public Radio, February 7, 2010, https://news.stlpublicradio.org/government-politics-issues/2010-02-07/kirkwoods-journey-separating-myths-and-realities-about-meacham-park-thornton-part-2.