By David S. Rotenstein

“Decatur Day is part of history. It’s a part of Black history. It’s a part of the Black culture,” Chevelle Eberhart-Lee told me in a recent interview. “And if this day discontinues, it’s like erasing a part of history.” Eberhart-Lee’s family has been in Decatur for more than a century. Her great-grandparents founded one of the city’s oldest Black congregations, Lilly Hill Baptist Church. She knows her history and she knows Decatur.

We spoke by phone in August after she sent me an email that read, “I just wanted to let you know that the City is trying to get rid of Decatur Day. . .They are slowly erasing the history of City of Decatur especially that of the Black community.” Decatur Day is the one-day reunion held by current and former Decatur residents. Until 2023, it was held in a city park, McKoy Park. After I received Eberhart-Lee’s email, I reached out to other Decatur residents whom I have interviewed since 2011 for my research on gentrification and erasure in the city. The responses were consistent: “People in the neighborhood are saying the whites don’t want Blacks at the park.”

To understand the conflict playing out in 2023, it’s essential to understand Decatur’s history. Decatur is an inner-ring Atlanta suburb located about six miles east of the Georgia State Capitol. Founded in 1823, the city sits in Jim Crow’s broad shadow, almost literally: Stone Mountain is seven miles in the opposite direction from Atlanta. Anti-Black racism, antisemitism, and nearly a century of serial displacement are blemishes that no amount of municipal boosterism and public relations spin can erase. Though Decatur as a place inhospitable to Blacks, Jews, and Muslims is firmly entrenched in the historical record, the municipal policies and hostile actions by residents towards non-white, non-Christian residents and visitors have also made it a hotbed of conspiracy thinking.[1] This article unpacks some of the baggage surrounding the city’s decision to move Decatur Day in 2023.

A Crash Course in Suburban Serial Displacement

African Americans have been a part of Decatur since the city’s founding. After emancipation, Black residents began building a community that included churches, homes, and businesses. Like many Southern cities during and immediately after Reconstruction, Black residents shared blocks with white residents.[2] Between 1900 and 1910, census data and fire insurance maps show that Decatur’s Black population began concentrating in two spaces near the courthouse square. The largest became a congested ghetto teeming with single- and multifamily homes, several churches, and Black-owned businesses. The low-lying area adjacent to an unnamed creek became known as “The Bottom,” and the higher spaces were known as “Beacon Hill.”[3]

The concentration of Black residents into The Bottom and Beacon Hill corresponded with changes taking place in other cities, and it happened around the same time as the Atlanta pogrom of 1906, a three-day period of white-on-Black violence. Racist municipal policies, including a racial zoning law, and the South’s prevailing Jim Crow system created the ghetto that most people simply recall as the Beacon Community.

By the time that the US Congress passed the public housing law in 1937, Beacon was filled with small frame homes that lacked plumbing and other modern amenities. The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) described the space as the “Negro area in Decatur” in the area description for the Atlanta Security (redlining) map. Though the unnamed assessor described many favorable attributes, including its proximity to the city’s business district, schools, churches, and the Black “business center,” it got a hazardous (D) rating due to its racial composition and detrimental influences: “Less than 10% of streets paved. Difficulty of rental collections. Poor repair condition of properties.”[4] It was ripe for the city’s new public housing authority to label as blighted and to target as a slum in need of clearance.

In 1939 construction began on the Allen Wilson Terrace apartments (later known by Black Decaturites as the “OPs” or “old projects”), a segregated, all-Black, two-hundred-unit public housing complex. The new housing created additional class divisions in a space where segregation concentrated people with different economic, educational, and religious backgrounds into an involuntary community. The people living in the new apartments became the “haves,” and those remaining in the surrounding community became the “have nots.”

Between the end of World War II and 1960, the city put additional pressures on Beacon. It continued to neglect the neighborhood’s infrastructure, and the city constructed a municipal trash facility and incinerator near Beacon’s center, adjacent to Decatur’s only Black public school and park. In 1949 Congress passed a new Housing Act that paved the way for cities like Decatur to take large swaths of land through eminent domain and transfer it to private developers. Urban renewal destroyed many Black communities throughout North America; Decatur’s program was just another entry in a growing government table.

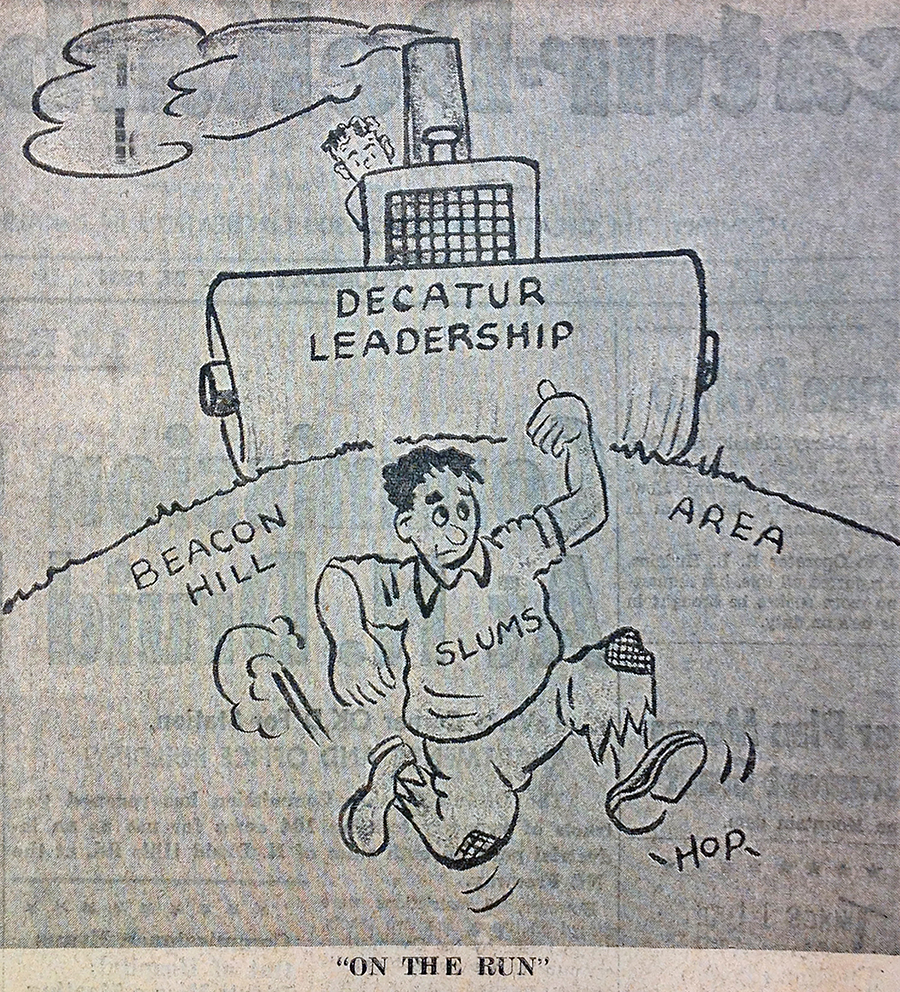

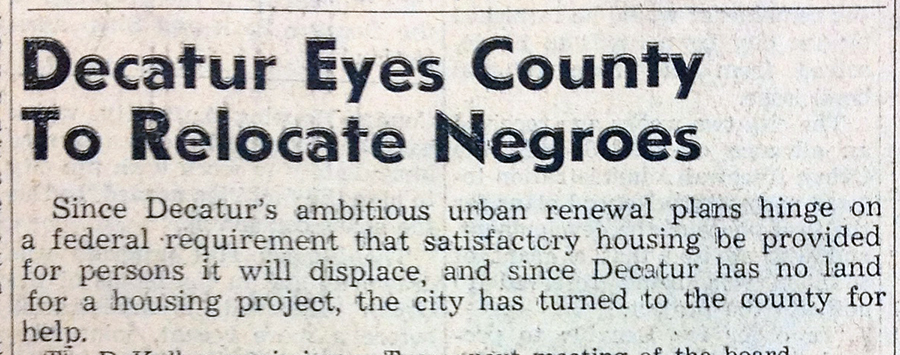

Flush with federal cash and a legal justification to seize property, Decatur embarked on several urban renewal phases during the 1960s. It transformed the remainder of the Beacon Community into county offices, a new high school, and commercial spaces. New public housing, all Black, joined the Allen Wilson Terrace apartments. Gateway was one of the new public housing complexes. It ended up being built after city leaders aborted a plan to relocate all the remaining Black households (not living in Allen Wilson Terrace) to unincorporated DeKalb County. One headline at the time read, “Decatur Eyes County to Relocate Negroes.”[5] Decatur completed three urban renewal projects in the Beacon Community between 1960 and the early 1970s. Beacon Hill Projects 1 and 2 cleared most of the area, displacing 231 Black families and 11 white families.[6]

City leaders received vigorous pushback from Black pastors and from federal officials. Despite earlier claims that no local land could be found to house the displaced people, city officials subsequently were able to build the Gateway apartments for displaced Black Decaturites.

Displacement continued in Decatur through the remainder of the twentieth century and intensified in the early aughts, as gentrification converted small homes into McMansions and Black spaces into white ones. According to US Census data, Decatur lost more than half of its Black population between 1980 and 2014. In the city’s once predominantly Black Oakhurst neighborhood, small builders flipping properties demolished more than 120 homes. Some offered buyers the opportunity to purchase “historically inspired” homes that were more than twice the size of the existing homes and in excess of double to triple the purchase price prior to demolition.[7] Marginalization and alienation, coupled with skyrocketing property taxes, were the main displacement drivers.[8]

The people moving out were mostly Black, and new residents were almost all white. People displaced in this phase were children in the late 1930s when the Bottom was razed and adults when urban renewal destroyed the rest of Beacon. Some had been displaced by urban renewal in neighboring Atlanta, and they found their suburban dream homes in the South Decatur neighborhood that became Oakhurst. Around the turn of the twenty-first century, predatory real estate speculators repeatedly pursuing them to buy their homes, coupled with municipal policies that encouraged teardowns and racial hostility, created an environment for conspiracy thinking. Black Decaturites began speculating and talking about official plans to turn the city white by expelling all the African American residents. A contemporary legend, “The Plan,” took root there as it did in Washington, DC, and other North American cities.

“The Plan,” which posits a white conspiracy to displace and eradicate Black people, is a narrative that derives from more than a century of lived experiences among people of African descent experiencing displacement. What matters with regard to “The Plan” isn’t whether there really is a cabal of conspiring whites; what matters is the belief held by so many people and how that belief informs their behavior.[9]

Mitigating Root Shock

“Root Shock is the traumatic stress reaction to the destruction of all or part of one’s emotional ecosystem,” wrote psychiatrist and urban scholar Mindy Thompson Fullilove.[10] It appears in communities experiencing displacement, and its symptoms include psychological trauma, financial loss, and instability.[11] Decatur Day is one of several initiatives that current and former Black residents of the city use to reclaim their community and their histories. It is Black Decatur’s balm for healing root shock. Erased from municipal histories and commemorative landscapes, Black Decaturites rely on informal and formal gatherings to sustain bonds bent and broken by displacement. They are quotidian, like weekly church gatherings. And they are the irregular events where people come together to mark life passages and holidays. These include the annual Thanksgiving Day football games in Ebster Park and Decatur Day.

“It’s how we reconnect. It’s how we reconnect as African Americans in Decatur, because for so long in the city of Decatur, we were not welcome in Decatur, you know,” explained resident Veronica Edwards. “It was just a gathering and reuniting for the African Americans.” McKoy Park is a city park in Oakhurst. It was where the event happened every year, except for the two years the event didn’t happen because of COVID.

Decatur residents and people in the Decatur diaspora planned for months each year to converge on McKoy Park, where they’d enjoy grilled food, music, and lots of fellowship. It was a super-reunion of sorts. Within the larger event, classes of Decatur High School graduates held their reunions. Decatur Day is Black Decatur’s biggest social event. Attendees have deep attachments to the event and the space. It’s part of a larger Black tradition of reunions held on an annual cycle in communities where natural and cultural disasters have disrupted lives.[12]

Displacing Decatur Day

As was true within the Beacon area during the twentieth century, Black Decaturites—city residents and those living in the diaspora—have many communities. There is no monolithic “Black community.” There are the anchor residents: homeowners living there since the 1960s and their children. There are the public housing residents. And there are the middle-class Black newcomers. Each has different values and attachments to the city and its spaces. Decatur Day’s participants tend to be part of the city’s old guard, folks whose families trace their stories to the OPs and to Oakhurst. They comprise the event’s stakeholder inner circle.

That inner circle began hearing whispers of possible changes to Decatur Day during the 2022 gathering. The rumors swirled among events that had taken place in the years before COVID disrupted Decatur Day. These included an increased police presence and more adversarial interactions with the white residents living near the park.

Despite municipal public relations campaigns to burnish the city’s image as a liberal and progressive city, Decatur remains a place where Black residents and visitors are subjected to daily overt and covert acts of anti-Black racism. Whether it’s police racial profiling or daily encounters on city sidewalks, Decatur remains a racially hostile city.

Reporting by news organizations on Decatur’s racism forced the city to confront its hemorrhaging Black population and the loss of affordable housing. Yet Decatur remains a news desert, a place devoid of dedicated and informed press coverage of the Black communities there.

Press releases and social contacts with a handful of Black residents at city-sponsored festivals aren’t effective pathways to understanding displacement and racism in Decatur. A local blog that began publishing in 2013 is a tool easily manipulated by city leaders and the real estate interests driving displacement and gentrification.[13] It fails to provide essential coverage of racism and gentrification at a critical juncture in the city’s history. It also lacks access to the whispers and voices with deep community knowledge about Decatur Day as well as the real and perceived threats to the annual event. With no one in the media talking about racism and with no journalists accessing the city’s hidden transcripts, the news about changes to Decatur Day was limited to Facebook timelines, email chains, and frantic telephone calls among stakeholders.

In my 2019 Journal of American Folklore article on gentrification in Decatur, I quoted a Decatur native who recounted his experiences with racism in the neighborhood dog park:

Barnes was a regular visitor to Oakhurst’s dog park. “I know that the people there, you have very few people that warm up to a Black guy and his dog,” he explained. “And everybody else knows each others’ names and your dog’s name. You know my dog gets more respect in the city than I do.” He stopped going to the dog park after new white residents mobilized to prevent a developer from buying the park and building new homes. In 2015 I asked him about the dog park and he said, “If they won’t stand up for the Black folks, I’m not going to stand up for their ‘fucking dog park.’”[14]

Tony Stevenson grew up in Decatur and now lives in Atlanta. His family was among the first wave of Black homebuyers to move into Oakhurst in the 1960s. He’s been going to Decatur Day for about fifteen years. The sixty-eight-year-old has seen firsthand how racism in Decatur has morphed from Jim Crow into something different, something worse.

“I came up during the civil rights movement,” he told me in an interview this summer. “I was a little boy, but I remember all of that. I remember the time when we couldn’t ride on the front of the bus. We had to get in the back of the bus. I remember all of that.”

And now?

“It’s not no different. It’s a little different, but they just flipped the script,” he says. “So racism is here, it’s worse.” Worse because it’s easier to hide.

He gave me several examples, but one really resonated because of what I had written in the Journal of American Folklore. Stevenson hasn’t had great experiences with Decatur’s white residents in the twenty-first century:

You know, you walk by them and speak and say “hey” or “how are you doing,” and they’ll look at you like, and don’t speak, and keep walking.

They walk their dogs on the sidewalk and then you’ve got to get off the sidewalk to let them and their dog by. Really? And they look at you like you don’t belong on the sidewalk.

In Decatur, Black people are expected to cede space to whites, whether it’s housing or a public sidewalk or a city park.

Renee (a pseudonym) has been attending Decatur Day for nearly thirty years.[15] She grew up in the Beacon Community. “My parents lived on Atlanta Avenue, and they pushed us out of our home and pushed us into the projects. We lived in this project called Gateway,” she told me.

Several episodes involving adversarial encounters with white residents living next to McKoy Park raised alarm bells in Renee’s mind. One in particular stands out. It happened one or two years before COVID. She described how Decatur Day veterans know to come early and stake out a spot before all the good, shady spaces are taken. She then said,

So this Black guy had his spot, and he had his stuff on it. This white guy came up and he was going to have his little girl, I guess, a birthday party and pushed his stuff to the side.

And the guy said, “No, no, no, this is my spot. This is my spot.” He had a cloth on the table and everything. He had his stuff on there. And I said to myself, we’re about to have some problems.

Renee and others learned in late July that Decatur Day would not be held in McKoy Park this year. Decatur Parks and Recreation Department Director Gregory White unilaterally decided to move the event to a green space in the former Beacon Community. Until 2014 it had been a block where several of the original Allen Wilson Terrace buildings were located. Like public housing complexes throughout North America, it was redeveloped. The green space has remained vacant since.

White disagreed that complaints by white McKoy Park neighbors played any role in the decision. He rebuffed comments made by all the Black residents I interviewed, who assert that the white neighbors don’t want the large number of Black people in the park. “That’s not true,” White told me in a telephone conversation. “Some people are making up some narratives.”

Requests for interviews with Decatur City Manager Andrea Arnold and staff in the public information office went unanswered.

Yet among the people I spoke with after receiving the first email about Decatur Day, all but White firmly believe that anti-Black racism in the gentrified Oakhurst community is the reason for the relocation. And they believe that the move is a first step towards ending Decatur Day altogether. Framed in context with other beliefs and stories told about life in Decatur, the Decatur Day move was just another part of “The Plan.”

History and Public Policy

Decatur goes to great lengths to protect its image, its brand, as a liberal and progressive city. In addition to a robust municipal public relations team, the city also published a nineteen-page “Brand Use and Style Guide.” Erasure and silencing are key devices in the city’s toolkit to keep residents, journalists, and others on brand. Erasing and whitewashing history is simpler than confronting it. Historian Elizabeth Belanger characterized the racism I have documented in my work as “state-sponsored erasure.”[16]

A different approach to public policy, that wasn’t informed by structural racism, might have yielded different results with the Decatur Day relocation and other episodes in recent history. A better understanding of root shock and the frames that people use to understand daily life might have helped city officials struggling with ways to balance complaints about Decatur Day and stakeholders’ beliefs. If Decatur has found a cure for its racism in such things as its dubious Better Together program, then city officials, residents, and the press don’t need to look to history for guideposts in making public policy decisions. Or do they?

Several of the people I interviewed for this article once lived in the Gateway apartments, the same complex developed in the 1960s after Decatur leaders were forced to abandon their plans to displace Blacks living outside the existing public housing. Fast forward half a century to 2014, when the City of Decatur was planning to demolish the Gateway apartments. Decatur city officials contemplated relocating families outside the city limits during the twenty-first-century redevelopment. That plan would have required children living in the apartments to enroll in non-City of Decatur schools. Public outcries against disrupting the students’ education resulted in the city abandoning the temporary schooling proposal.

Would a better understanding of Gateway’s history have resulted in a different process for the twety-first-century redevelopment? Would it have avoided inflicting additional emotional trauma on people living with the baggage of nearly a century of serial displacement? Perhaps. The same is true of what happened with Decatur Day in 2023. A better understanding of history certainly couldn’t hurt. Better communication with stakeholders, informed by history and racial realities, not branding, boosterism, and alienation, would also be beneficial in circumstances like these. History shouldn’t be an elective when it comes to public policy making in spaces defined by serial displacement, racism, and erasure.

David Rotenstein is a public historian and folklorist living in Pittsburgh. He frequently writes on historic preservation and gentrification and is working on a social history of numbers gambling in Pittsburgh.

Featured image at top: Decatur Day. Undated photo courtesy of a Decatur resident who requested anonymity.

[1] David S. Rotenstein, “The Decatur Plan: Folklore, Historic Preservation, and the Black Experience in Gentrifying Spaces,” The Journal of American Folklore 132, no. 526 (2019): 431–51.

[2] Thomas W. Hanchett, Sorting out the New South City: Race, Class, and Urban Development in Charlotte, 1875-1975 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998).

[3] David S. Rotenstein, “Decatur’s African American Historic Landscape,” Reflections (Ga. State Historic Preservation Office) 10, no. 3 (May 2012): 5–7.

[4] “Area Description-Security Map of Atlanta, Georgia,” (Area D7). Robert K. Nelson, LaDale Winling, Richard Marciano, Nathan Connolly, et al., “Mapping Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, accessed August 31, 2023, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=15/33.767/-84.32&city=atlanta-ga&area=D7&adimage=2/40/-152.799.

[5] DeKalb New Era, July 27, 1961.

[6] Urban Renewal Project Characteristics, June 30, 1962 (Washington, DC: Urban Renewal Administration); Digital Scholarship Lab, “Renewing Inequality,” American Panorama, ed. Robert K. Nelson and Edward L. Ayers, accessed September 1, 2023, https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/renewal/#view=0/0/1&viz=cartogram&city=decaturGA&loc=16/33.7740/-84.3000.

[7] I documented the teardowns between 2011 and 2014 in this photoblog, https://gentrifiedsuburb.wordpress.com/. The “historically inspired” description comes from marketing copy published in ads and on construction signs by one company that was active there, Thrive Homes.

[8] ‘Tearing Down Oakhurst: An Oral History of Gentrifcation,” documentary derived from interviews done between 2011 and 2014, https://youtu.be/aKNlz71yqjI.

[9] David S. Rotenstein, “The Plan: An African American Belief Narrative,” Journal of Folklore Research, in press; Patricia A. Turner, I Heard It through the Grapevine: Rumor in African-American Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993); Gary Alan Fine and Patricia A. Turner, Whispers on the Color Line: Rumor and Race in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

[10] Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Root Shock: How Tearing up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do about It, 1st ed (New York: One World/Ballantine Books, 2004), 11.

[11] Mindy Thompson Fullilove, “Root Shock: The Consequences of African American Dispossession,” Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 78, no. 1 (March 2001): 78, https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/78.1.72.

[12] Francis Edward Abernethy, ed., Juneteenth Texas: Essays in African-American Folklore, 1st ed, Publications of the Texas Folklore Society 54 (Denton: University of North Texas Press, 1996); Gerald L. Davis, “‘Will the Circle Be Unbroken?’: African American Community Celebrations and the Reification of Cultural Structures,” in Jubilation! African American Celebrations in the Southeast, ed. William H. Wiggins and Douglas DeNatale (Columbia: McKissick Museum, University of South Carolina, 1993), 51–59; Gerald D. Jaynes, ed., “Encyclopedia of African American Society” (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2005), 312; Julie E. Miller-Cribbs, “African American Family Reunions: Directions for Future Research and Practice,” Perspectives 10, no. 1 (2004): 160–73; Nate Schweber, “Reunion for a Vanished Neighborhood,” New York Times, October 9, 2011, sec. N.Y. / Region, https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/10/nyregion/reunion-for-a-vanished-neighborhood.html

[13] Tilman Schwarze, “Discursive Practices of Territorial Stigmatization: How Newspapers Frame Violence and Crime in a Chicago Community,” Urban Geography 43, no. 9 (October 2022): 1415–36; Tilman Schwarze and David Wilson, “Silencing, Urban Growth Machines, and the Obama Presidential Center on Chicago’s South Side,” Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 4 (2022), https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/frsc.2022.835674.

[14] Rotenstein, “The Decatur Plan,” 441.

[15] People interviewed for this article were asked if they wanted to be identified by their names or by pseudonyms to protect them from retaliation.

[16] Elizabeth Belanger, “Race, History, and the Politics of the Local,” The Public Historian 45, no. 2 (May 1, 2023): 46.