The Metropole Bookshelf is an opportunity for authors of forthcoming or recently published books to let the UHA community know about their new work in the field.

By Gordon Mantler

In the winter of 1983, civil rights veteran and activist Al Raby wrote “The Meaning of Harold Washington’s Campaign,” an essay in which he attempted to capture the historical and political significance of Harold Washington’s candidacy for mayor of Chicago. Having been recently tapped as Washington’s campaign manager, Raby framed the campaign as a continuation and culmination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s coalition building during the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign, fifteen years earlier. Dr. King “believed in and gave his life so that poor Blacks, Latinos, and Whites could share the American dream,” wrote Raby, who had helped recruit King to Chicago in 1965. “Congressman Harold Washington comes out of that movement for human rights and, with our help, he can use the office of Mayor to achieve its goals…Today, here in Chicago, Harold Washington is continuing that civil rights movement.”

Indeed, Washington became the city’s first Black mayor on the strength of that multiracial urban coalition, winning three quarters of Latinos, 12 percent of whites, and an astounding 99 percent of Black Chicagoans who cast ballots. Nascent efforts at such coalition building in the 1960s had seemingly culminated in a dynamic electoral coalition in Chicago—not to mention Boston, Denver, San Antonio, and other multiracial cities—a short generation later.

Of course, it was more complicated than the linear trajectory Raby suggested. But, as I wrapped up my own research for my first book on the Poor People’s Campaign and its legacies, this document in the Harold Washington Library Center’s archive captured my imagination. And, roughly ten years later, that seed resulted in The Multiracial Promise, a new examination of the Harold Washington movement and moment, and the national implications his electoral victory and administration had for not just urban politics, but also national politics, from Jesse Jackson’s rainbow campaigns in 1984 and 1988 to the rise of so-called “third-way” politicians like Richard M. Daley and Bill Clinton. This Chicago story is, in fact, the era’s national story.

Much has been written about Washington, mostly by journalists who covered Chicago politics at the time or by an array of administration insiders. These accounts, understandably so, focus on Washington’s charisma and political skills, the historic political mobilization of the city’s African Americans, and the decline of the legendary Democratic machine after longtime Mayor Richard J. Daley’s death in 1976. But these accounts, while valid in many ways, too often understate the importance of all members of Washington’s coalition, the fragility of that coalition before the mayor’s untimely death in 1987, and the obvious limits to electoral politics alone. Thousands of activists across the city, of all races, classes, and genders, from Lu Palmer, Rudy Lozano, and Helen Shiller to Marion Stamps, Slim Coleman, and Linda Coronado, laid the foundation for Washington’s narrow victory. Without this activism, including years of issue-based organizing in their neighborhoods and massive voter registration efforts, Washington would likely be known as a respected congressman from the South Side but not necessarily the historic figure he became.

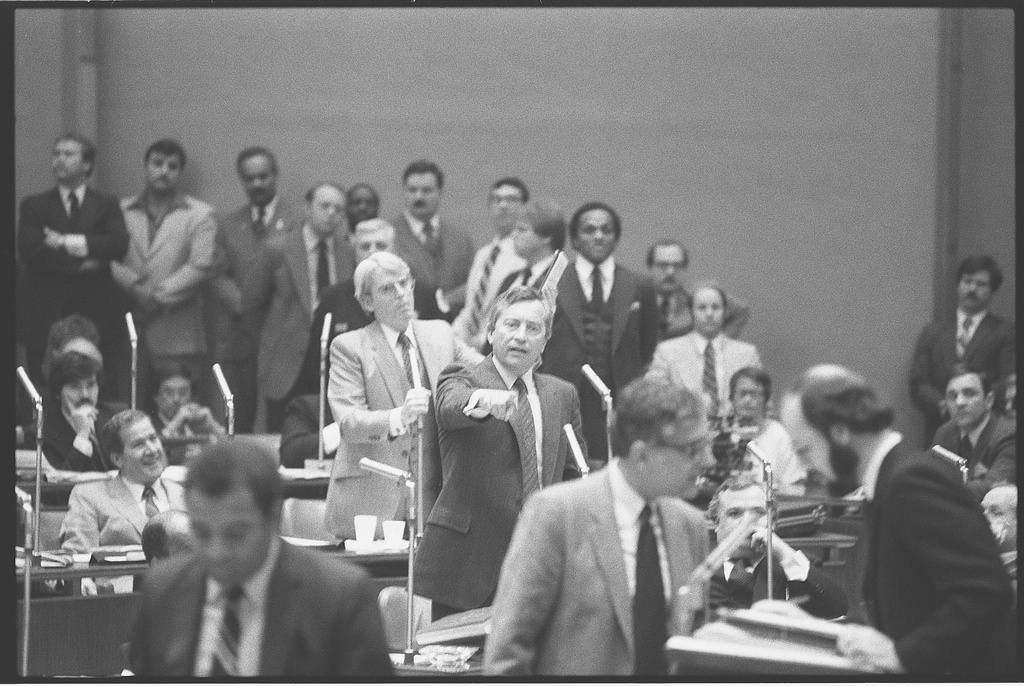

Past treatments of the Washington era also emphasize the campaign more than anything else. But despite the campaign’s striking social movement organizing and fervor, the administration that followed struggled to combat a range of structural obstacles. White supremacy, mass incarceration, deindustrialization, federal disinvestment in cities, dysfunctional institutions, and the Washington coalition’s own internal contradictions watered down if not outright blocked many of the administration’s promised reforms. Only when grassroots organizing by neighborhood-based activist networks across the city were able to sustain political pressure on the administration did genuine reform take hold—and usually only tentatively.

A few examples reflected this reality. While Latinos were essential to Washington’s urban coalition, key campaign promises to these partners went unaddressed six months into the administration, especially after Washington aide and confidant Rudy Lozano was killed. Frustrated with the administration’s lack of attention to their issues, a group of Latino allies to the administration threatened to hold a press conference announcing the formation of a Latino commission that would grade the administration on a range of issues, such as hiring, education, and health care. In response, the mayor formally announced the Mayor’s Advisory Commission on Latino Affairs and staffed it with thoughtful, independent activists from the community. Over the next several years, Washington proved an essential ally to Latinos, from declaring Chicago a sanctuary city for Central American refugees fleeing violence to establishing the city council’s first four Latino-majority districts and advocating for a Latino-majority congressional district. But these clear achievements only happened after Washington’s activist allies placed sufficient pressure on the administration to act.

In contrast, the tapping of historic figures such as Fred Rice and Renault Robinson as the first African American heads of the Chicago Police Department and the Chicago Housing Authority, respectively, were significant symbolic moments in the city’s history that led to very little change. Neither effectively challenged the dysfunction of their agencies, which continued to mistreat Black and Latino Chicagoans disproportionately—in part because genuine reform took more time and resources than the mayor could spare, especially amid white opposition. Moreover, activists who may have otherwise held Washington’s administration accountable too often gave him the benefit of the doubt because they were reluctant to provide ammunition to his white political opponents—even if their critiques were justified. Thus, the police and housing regimes under Washington continued to dehumanize already marginalized Chicagoans.

When Harold Washington died suddenly from a massive heart attack in 1987, the fragility of his coalition was laid bare. After all, coalitions, especially electoral ones, are inherently fleeting. That December, this reality allowed white veterans of the Daley machine to reassert themselves during the chaos after Washington’s sudden death. A Black caretaker mayor took over, only to be defeated fourteen months later by the boss’s son, Richard M. Daley, a quintessential neoliberal Democrat who ruled the city for twenty-two years and ushered in the yawning inequality that marks not just contemporary Chicago but most other major American cities in the twenty-first century.

In Chicago today, another progressive Black politician is mayor. Brandon Johnson, a former middle school teacher, labor union activist, and county commissioner, won a narrow victory against the city’s conservative former Chicago Public Schools CEO in a race that held some similarities to Washington’s forty years ago. White racial entreaties by Johnson’s opponent, Paul Vallas, were more coded than those in 1983, barely. But threats that a Johnson victory would send the city into convulsions of mayhem—that the police would quit en masse, for instance—simply did not happen. Just like such threats didn’t happen in 1983.

But Johnson faces many of the same challenges as Washington did, often grown worse since the 1980s due to neglect. If anything, along many measures Chicago is more segregated and more unequal in the twenty-first century. And the city has, arguably, even fewer resources to combat problems in education, mental health, housing affordability, migration, public safety, and climate change than it did forty years ago. The new mayor does have the most diverse and progressive city council in Chicago’s history—a group that could prove to be a reliable partner in navigating the city’s challenges, and certainly more reliable than Harold Washington’s council.

But as it was in 1983, those activists and voters who put Johnson into the mayor’s seat must stay engaged. That might be a tall order since voter turnout this past spring was roughly half that from 1983. The risk of political disengagement is high, and yet only continued pressure on the new administration will be how substantive urban reform can become more than just rhetoric.

Dr. Gordon Mantler is Executive Director of the University Writing Program and Associate Professor of Writing and of History at the George Washington University. He specializes in the history and rhetoric of twentieth-century US social justice movements, multiracial coalitions, public history, memorialization, and film, and writing pedagogy in history classes. His first book, Power to the Poor: Black-Brown Coalition and the Fight for Economic Justice, 1960-1974, was the inaugural volume in the Justice, Power, and Politics series at the University of North Carolina Press in 2013. His most recent book, The Multiracial Promise: Harold Washington’s Chicago and the Democratic Struggle in Reagan’s America, was published in March 2023 with UNC Press and focuses on multiracial electoral politics and community organizing in Chicago in the 1970s and 1980s. He has received numerous awards, including the first annual Ronald T. and Gayla D. Farrar Media and Civil Rights History Award for the best article on the subject.