Editor’s note: This post part of our theme for March 2023, Science City, an exploration of the ways cities and science have interacted over time and around the world.

By Nuala Caomhánach

The concerned look on their faces was enough to make me turn around and go home. Standing at the doorway of my shared office at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), my colleague hesitated, “Emmm, I am not sure you want to come in and see this?” What could be so bad that my colleagues barricaded the door like a crime scene. “What’s wrong?” I asked as I maneuvered around this human barricade. “A mouse pooped on your desk.” A mouse, I thought, oh okay.

Common house mice really earned their moniker at the museum. At night, as you wander off to an exit, you see from the corner of your eye the reflective floors bobbing—small brown mice scuttling off on their nocturnal business. When I looked at my desk, it was clear my colleagues did not know mice at all. This was not one mouse, unless it had some serious gastrointestinal issues. My desk was popcorned—the books, the chair, the mug—everywhere was covered in tiny, rice-sized brown droppings. As I started to shuffle the pellets into a pile with my bare hands, my colleagues looked on, aghast; one commented, “You can tell you are a scientist; that doesn’t bother you in the slightest.” And there, the innate tension of the human-animal interaction in urban spaces was laid bare.

Being a scientist was not a guarantee that unpalatable aspects of the natural world would not lead to disgust, but for my city-loving colleagues, the worry that the intrusion of “nature” was only one desk away was horrifying. That the scientist’s desk was solely targeted seemed to make logical sense for these science administrators. On some level I felt like the mice were making a statement—what exactly?

The scattered poop all over my desk reminds us of the lack of control we have over the dynamism and unpredictability of nature. If rodents and humans, as mammals, are doing mammalian things within the spaces of production and waste that are cities, how do we begin to understand the long-term impact to urban living? Examining the ways we order, reorder, and unorder urban nature offers a lens to understand how rodents, as cohabitants, are coevolving with us. Their evolutionary trajectory is also ours.

Our desire to separate care and control of the natural world in a dynamic ecological system is impacting us on a molecular level. The name rodent was coined by the English writer Thomas Edward Bowdich in 1830 from the Latin word “to gnaw”. [1] Gnawing is an apt verb to describe our desire to keep rodents hidden from our everyday lives as they nibble at the edges of our anxieties and stresses of city living.

On that same day in late September 2015, a video began circulating on social media platforms under the hashtag #pizzarat. Within weeks, it had garnered more than seven million views on YouTube—sufficient evidence that this mammalian experience of life in a big city resonated with the nation’s imagination. Pop culture sites such as BuzzFeed took note, but soon mainstream media like NPR and the New York Times captured the rodent’s story.[2] Unlike my desk mice who had merely left fecal traces of their presence, this fourteen-second video, shot by the comedian Matt Little, was a rat captured in real life. The rat in question wrestles with a slice of New York-style pizza, dragging it down the steps of a Manhattan subway station. Responses to the video varied from disgust to celebration.[3] Some interpreted it as evidence of poor sanitation, while others cast the rodent’s perseverance and sass as modeling true New Yorker behavior.

These polarized opinions, like so many unappetizing experiences in cities, reflect the discomforting impact of watching urban living—the voyeurism, the horror, the joy, and the fascination. For writer Joseph Mitchell rodents are “almost as fecund as germs.”[4] As a public health service doctor remarked to Mitchell, the “untrained observer…invariably spreads his hands wide apart when reporting the size of a rat he has seen, indicating that it was somewhat smaller than a stud horse but a whole lot bigger than a bulldog. They are big enough…without exaggerating.”[5] This pithy remark is also applicable to city sprawl, fecund in process and fecund in effect, but our arms are not quite wide enough to capture the city’s size.

Whilst our relationships with rodents can be as fleeting as the shelf life of the pizza rat meme, the rat’s celebrity can be seen as part of the history of anthropomorphism. Rebranded for the short attention span of social media culture, however, it also points to a profound transformation of interspecies ecologies that have reconfigured the material conditions of human-animal encounters in urban landscapes.

Rodents represent the vacillating categories nonhuman organisms inhabit and generate questions about care and systems of value in modern life. Rodents are our co-species, mirrors to our own behaviors as they inhabit our trash, waste systems, homes, and offices. As the anthropologist John Hartigan stated, “Care operates in two basic modalities: a form of attention and a set of practices—interests and activities. How these align or diverge is a constant question with care…These dynamics of care become a good deal more complicated when they are enacted or exerted across species lines…such as those involved with care of the species.”[6] When considered as “vermin” or “pests,” we, as city dwellers, do not have to care about them nor care for them, rather we wish rid of them, for their untimely deaths. It can be a challenge to see their value other than as model organisms for studying human diseases.

Natural History Museums offer a window into the way care is reconfigured depending on what value the rodent may or may not have. Mice like my desk visitors are placed under pest control, while other mice are given absolute and ongoing care. This is care instilled with a scientific value. By examining three different kinds of “rodent value” systems—as a teaching tool, a scientific object, and an organismal analogs—we get to understand the longer historical relationships we have with the nonhuman in cities. As cities experience unconstrained growth, collecting and studying rodents offers vital information to understanding how we are co-evolving in real time.

Unusual Suspects

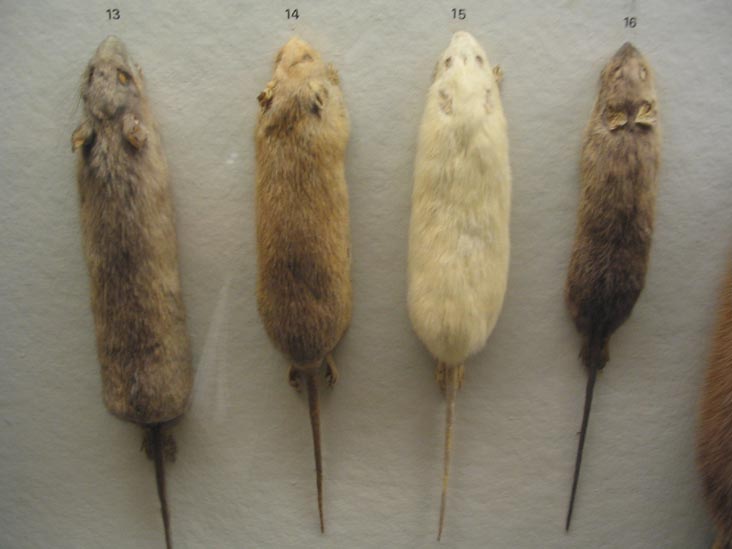

In the Hall of New York State Mammals at the AMNH, museum visitors view dioramas of rodents lined up like fur coats on a coat rack in species groupings. Discrete specimens are arranged as a didactic tool; the viewer is invited to teach themselves how to understand species identification. By comparing the morphological features of various mammal species, visitors experience the first steps in museum science: comparative gross anatomy. The Hall is known colloquially as the “road-kill hall” as the mammals are not taxidermied or posed in the more traditional manner for exhibiting in dioramas. The pelts are mounted upright onto the diorama display wall with their backs facing the visitor. These rodents receive less care—an occasional dusting—than the rodents found in the scientific collections tucked away in metal drawers in the upper floors where the public cannot visit. If the subway is like steerage class, then the Department of Mammalogy is first class as collection managers and curators tend with kid gloves to the 275,000 specimens of different mammal species. In this collection, rats and mice are a very small fraction of the larger whole. In so many ways these rodents are loved to death.

A private detective-style door surrounded by the casts of rhinoceros horns forms the entryway into the Department of Mammalogy. The door opens onto a hallway that houses rooms full of closed-doored white metal cabinets filled with labeled and well-ordered specimens. In 1885, when Joel Asaph Allen became the first curator of the department, he noted, “There was not even a nucleus of a study collection.” [7]Allen was less concerned about the local rats and mice; they were easy to capture if need be. To build the mammal collection Allen needed all rodent species, and in this age of empire and obsessive collecting, the museum funded expeditions around the globe. In 1909 Herbert Lang and James Chapin set sail for the Belgian Congo, and five and a half years later, rat and mice specimens were brought to the museum amongst more prized possessions like the okapi and square-lipped rhinoceros.

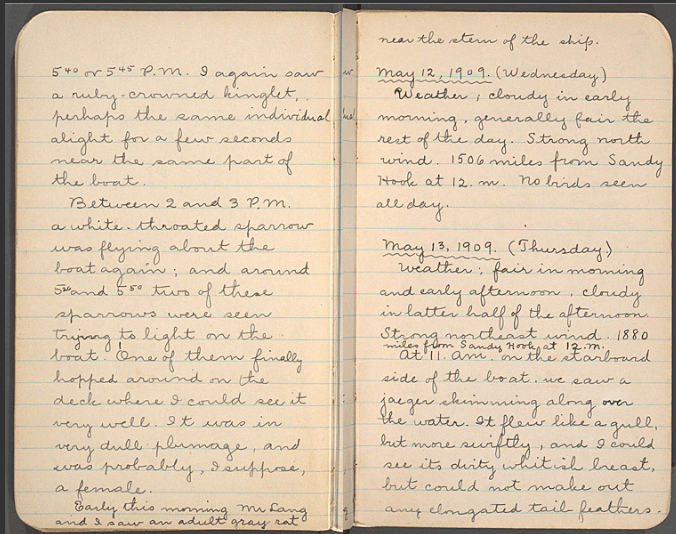

Rodents on expeditions blurred the boundaries between problem and prize. Rodents on ships destroyed specimens, even specimens of their own kind. Chapin, Lang’s nineteen-year-old assistant, wrote journal entries about daily life on the expedition. His diary is peppered with references to rodents. Not long after they left Sandy Hook in New York, they observed an “adult gray rat” on the stern of the deck.[8] In Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) Chapin noted “a great many rats about the houses, much like M. norvegicus, but with larger ears, I think.”[9]At Tshumbiri (also part of today’s Democratic Republic of Congo), as word got out that they required rodents, “a young striped rat” was sent to the crew from the local mission.[10] Collector unknown. Word had gotten around as the head of the American Baptist Missionary Union, Reverend A. Billington, supported the scientific focus of the expedition. The reverend’s wife, Mrs. A Billington, noted that “For the American Gentlemen who are collecting rats, etc. with Mr. Billington’s compliments. If some dead rats reach the steamer, they are to show the kind found here up [to] 15′ 16 inches, nose to tip of tail.”[11] The expedition collected numerous rat species, and noted rodent remains in the stomachs of bigger mammals, such as a Genetta that “some natives brought us.”[12]

Chapin rarely mentions the locals who carried out the labor to capture the rodents, but we do know some were women. In Stanleyville (now Kisangani) an old coffee plantation covered in grass and bushes was cut down, and “a gang of women from the prison [were] cleaning it up…On these two days we received a number of rats…”[13] The rats were “especially interesting in the way the tail varied in different individuals. Some had the tail complete…Others had no visible tail at all, and a few had bob-tails, that had obviously been broken off…One of the bob-tailed individuals, when brought to us, had the skin of the tail broken in a complete circle. Whether this would cause a piece of the tail to drop off I do not know.”[14]

Lang and Chapin “decided that the small brown rat, so many of which have no tails, must lose them simply by their being broken off. Not only is the skin of the tail, as well as that of the whole body, very tender, but the attachments of the caudal vertebrae are very weak, so that the tail, in a dead specimen at least, breaks to pieces very easily.”[15] To pack the specimens, Chapin and his colleagues removed their skins and dried them, and labeled them while taking notes in their field notebooks. This preserved the specimens, in theory, for the long journey home. The expedition discovered several kinds of rats and a few dormice. Rats seemed abundant and Chapin noted that the “natives here are not at all ashamed to eat rats and mice, which they are very expert at catching.”[16] It seems that the Lang crew did not partake in this delicacy, yet without the tacit knowledge of the locals, the expedition would not have been so successful in both surviving the humid environment and field collecting.

Once returned to New York, these specimens were reprocessed. The skins were cleaned and stuffed with cotton, labels checked, and the rodent corpses carefully placed into the metal drawers for scientific posterity. Species such as the giant elephant-shrew, with the “body of a red pig, nose of an elephant, tail of a giant rat; not a mouse, but a real animal,” confounded scientists as they were hard to place into species categories.[17] Yet, over the years the collection of diverse mouse and rat species expanded—more expeditions, more researchers, each bringing with them their own scientific missions to understand the natural history and evolution of these organisms. The collections not only increased in institutional value but also in scientific opportunities. These specimens could be used to study change over time, especially in the ever-increasing cityscapes.

Genetic Hitching in the City

Rodents, like humans, are highly adaptable to their environments. Rat and mice genomes offer clues about this ability to thrive and survive in sprawling urban ecologies. Recent studies have identified dozens of genes involved in movement, behavior, and diet that scientists perceive help rodents live on the mean streets of the Big Apple.[18] Whereas Lang and Chapin relied on local collectors, biologists in New York use a paleo-diet approach to trap rats, an enticing mix of oats, bacon, and peanut butter. Comparative studies using full genome sequences allow scientists to compare rats with those in other locations, such as rural northeast China, the presumed ancestral home of brown rats. By pairing genome sequences from New York and China and reading them for differences, researchers can look for selective sweeps. Selective sweep refers to an evolutionary process by which a new advantageous mutation eliminates or reduces variation in linked neutral sites as it increases in frequency in the population. This phenomenon is also called “genetic hitchhiking.”[19] By shortlisting genes that harbor the potential signature of a selective sweep, researchers suggested that changes in rat behavior, at a DNA level, may be occurring in response to changes in local predators or to novel stimuli in urban settings. Some genetic motifs suggest adaptations in location behavior to help them move more easily through pipes and sewers.

The crucial point to these kinds of studies is that urban rats and mice are so closely linked to human city dwellers that it is possible similar genetic changes have occurred in both species. Diet seems to be the most striking comparison. Researchers have shown that it is not just humans with a sweet tooth or love of junk food. Rats seem to also be suffering from diet-related illnesses found in urbanites. University of Texas in Austin population geneticist Arbel Harpak argues that rats have undergone genetic shifts parallel to humans, leaving them susceptible to similar health threats. As Harpak put it, “In New York you can see them eat bagels and beer; in Paris they like croissants and butter. They adapt in amazing ways.”[20] Exactly when brown rats went through most of these genetic changes is unclear—the ongoing difficulties of pinpointing the moving target that is microevolution. We are left pondering if rats are merely being rats by scavenging and being opportunists, or has urban life altered their DNA. The former gives us humans a free pass, but the latter leaves open the question of how evolutionary forces are changing us as a species. Perhaps this is merely our evolutionary history in action, and cities are as natural as landscapes we evolved from. The next step in this puzzle is for researchers to collate data from rat collections in museums and trace change in recent history.

Conclusion

If it’s a comfort to know humans are not alone in suffering from the stresses of city life, cities also offer perspectives on reorienting our relationships to the nonhuman. By tracing the hierarchical ranking of rats and mice as they move from sewers to desks to collection drawers, we can learn a great deal about how cities function as ecological systems. Paying attention to these interactions can remind us that the places we consider most human, and by default least natural, are in fact teeming with nonhuman organisms and their own fast-paced lives. The mice scuttling past the Plateosaurus engelhardti in the AMNH at midnight and the rat carrying the pizza to some secret subway space are urbanites just like us. What we call “pests” or “specimens” represent our projections and anxieties onto other forms of life. Pizza rat subverts the “natural” order expected by city-dwellers, provoking fascination, anxiety, and in some cases hunger, in equal measure. Perhaps the divide is nonexistent and our joy at the rat dragging the pizza five times its size reflects our own gluttonous consumerism and the need to find joy in bustling cities.

Monitoring rodents has never been an exact science, but New York has had brown rats since the time of the Revolutionary War. As we increase in population, so do they. For over a century, city officials have tried and failed to eradicate them, but New Yorkers never give up. In December 2022, New York City advertised for a newly created position of “director of rodent mitigation.”[21] This new “Rat Tzar” has a behemoth task ahead of them. But perhaps these clever hairballs will figure out that the safest place is around my desk at the American Museum of Natural history.

Nuala Caomhánach is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at New York University and a research scientist in the Invertebrate Department at the American Museum of Natural History. Her dissertation “Curating Madagascar: The Rise of Phylogenetics in an Age of Climate Change, 1920-2023” examines the relationship between scientific knowledge, climate change, and conservation law in Madagascar. Nuala is a contributing editor at the Journal of the History of Ideas Blog, and co-produces the Not That Kind of Doctor podcast that invites PhD students to discuss their research.

Featured image (at top): Male Adult Armoured Hero Shrew (Scutisorex congicus). Image from J.A. Allen, “The American Museum Congo Expedition Collection of Insectivora,” Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History, VOL XLVII, 1922-1925 (New York: Published by Order of the Trustees).

[1] Thomas Edward Bowdich, “An Analysis of the Natural Classifications of Mammalia: For the Use of Students and Travellers,” (Paris: J. Smith, 1821).

[2] Renee Montagne, “A Rat in New York City Shows How We All Feel About Pizza,” NPR, Sept. 22, 2015, http://www.npr.org/2015/09/22/442441780/arat-in-new-york-city-shows-how-we-all-feel-about-pizza; Emma G. Fitzsimmons, “‘Pizza Rat’ Prompts a Collective ‘Ew’ and Debate on Cleaning New York Subway,” New York Times, Sept. 22, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/09/23/nyregion/pizza-rat-spurs-debate-on-how-to-clean-up-new-yorks-subway-system.html; Chelsea Marshall, “This Rat Took Some Pizza On The Subway And Everyone Lost Their Shit,” BuzzFeed, Sept. 21, 2015.

[3] Margarita Noriega, “Pizza Rat: New York City’s infamous rodent, explained,” Vox, Sept. 21 2015, https://www.vox.com/2015/9/21/9366729/ny-subway-pizza-rat.

[4] Joseph Mitchell, “Thirty-two Rats from Casablanca,” The New Yorker, Apr. 29, 1944, 30.

[5] Mitchell, “Thirty-two,” 32.

[6] John Hartigan Jr., Care of the Species: Races of Corn and the Science of Plant Biodiversity (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 217.

[7] Joel Asaph Allen, “Autobiographical Notes and a Bibliography of the Scientific Publications of Joel Asaph Allen,” The Museum (1916), 34.

[8] James Chapin, Diaries, Book 1: May 8, 1909 to July 17, 1909, American Museum Congo Expedition, AMNH Library, 2.

[9] Chapin, “Diaries, Book 1,” 20.

[10] Chapin, “Diaries, Book 1,” 21.

[11] Chapin, “Diaries, Book 1,” 21.

[12] James Chapin, Diaries: Book 2: July 18, 1909 to Oct. 31, 1909, American Museum Congo Expedition, AMNH Library, 6.

[13] Chapin, “Diaries: Book 2,” 8.

[14] Chapin, “Diaries: Book 2,” 8.

[15] Chapin, “Diaries: Book 2,” 9.

[16] James Chapin, Diaries, Book 3: Nov. 1, 1909 to Feb. 5, 1910, American Museum Congo Expedition, AMNH Library, 15.

[17] James Chapin, Diaries, Book 6: Dec. 10, 1914 to Mar. 6, 1915, American Museum Congo Expedition, AMNH Library, 11.

[18] Arbel Harpak, Nandita Garud, Noah A Rosenberg, Dmitri A Petrov, Matthew Combs, Pleuni S Pennings, and Jason Munshi-South, “Genetic Adaptation in New York City Rats,” Genome Biology and Evolution 13, no. 1 (Jan. 2021); Matthew Combs, Kaylee A. Byers, Bruno M. Ghersi, Michael J. Blum, Adalgisa Caccone, Federico Costa, Chelsea G. Himsworth, Jonathan L. Richardson, and Jason Munshi-South, “Urban Rat Races: Spatial Population Genomics of Brown Rats (Rattus norvegicus) Compared across Multiple Cities,” Proceedings of the Royal Society, B (2018), http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.0245.

[19] Takeshi Kawashima, “Comparative and Evolutionary Genomics,” in Encyclopedia of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology: ABC of Bioinformatics, Shoba Ranganathan, Kenta Nakai, and Christian Schonbach, eds., (Elsevier 2018), 1420.

[20] Robin McKie, “Beer and Bagels Please: New York Rats Evolve to Mirror Human Habits,” The Guardian, Mar. 20, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/08/new-york-rats-evolve-to-mirror-human-habits.

[21] Dana Rubenstein, “Wanted: N.Y.C. Rat Overlord With ‘Killer Instinct.’ Will Pay $170,000,” New York Times, Dec. 2, 2022. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/02/nyregion/nyc-rat-control-job.html.