Editor’s note: In anticipation of the Urban History Association’s 2023 conference being held in Pittsburgh from October 26 – October 29, The Metropole is making the Steel City its Metropolis of the Month for January 2023. The CFP remains open until February 20, 2023. See here for details.

By Drew Simpson and Dan Holland

When the news broke in 2018 that Pittsburgh was a serious contender for Amazon’s second headquarters (HQ2), the city and region buzzed as residents shared their opinions on the development. Some were elated, believing that a successful bid meant good-paying tech jobs and corporate investment from one of the most powerful companies of the twenty-first century. And the fact that Pittsburgh was even in contention for HQ2 seemed to validate several decades of elite-led economic development efforts known as Pittsburgh’s “Renaissances.”

While some Pittsburghers celebrated, others worried. The city and region’s post-industrial transformation was never as smooth as boosters often implied. Inequality persists today. More technology money threatened to chip away at one of Pittsburgh’s most important comparative advantages—it’s high livability rankings, which were helped in no small measure by a still relatively affordable regional housing market. Perhaps to try and assuage these concerns, boosters created a splashy promotional campaign complete with a video titled “Future Forged for All,” which interspersed historical film with present-day images and stories featuring regional landmarks, people engaging in recreation and commerce, and of course, local fans cheering on the Pittsburgh Steelers.[1]

Beyond the high production value and clear investment by regional boosters, the video’s most interesting aspect (and what makes it an excellent teaching tool) is how it captured a particular mythology of Pittsburgh’s past and its transition over the long twentieth and early decades of the twentieth-first centuries. This mythology holds that modern Pittsburgh is the result of an inevitable process both forced by circumstances out of locals’ control while simultaneously bolstered by intentional decisions made by regional leaders. While there is truth in this telling, too often this story’s lack of complexity flattens accountability and limits the potential for future change.[2]

Today Pittsburgh continues to be a place that is studied by urban historians, pundits, and others, who look to its post-industrial transformation to draw lessons about the past and the future for communities within and outside of the Rust Belt. Pittsburgh certainly has inspired us. Both authors are not only scholars of Pittsburgh but also live and work in this community. Therefore, the story of what Pittsburgh was, is, and can be is deeply personal. As we welcome UHA members to Pittsburgh for the 2023 biannual meeting, we were asked to take stock of where “the Pittsburgh story” stands today and think about how historians can use the existing scholarship on Pittsburgh as a guide to understanding not only this city but also their own. Doing this, we hope, will help create an accurate and nuanced understanding of the past so that the future that is “forged” for cities in the United States is inclusive, just, and equitable.

Making Pittsburgh Industrial

Industrial Pittsburgh had many names, including the Steel City, the Forge of the Union, an Arsenal of Democracy, and even Hell with the Lid Off. Its emergence as a center for glass, iron, and steel production owed much to specific individuals like James O’Hara, Andrew Carnegie, and Henry Clay Frick, and its location at the headwaters of the Ohio River and near rich coal seams. The glass and boatbuilding industries were a critical part of early industrial Pittsburgh, and Allegheny County’s glass factories produced “nearly 27 percent of all glass manufactured in the United States” by 1880.[3]

But Pittsburgh’s relationship with iron and steel, forged primarily in the years after the Civil War, has been its most enduring legacy. [4] Industrial Pittsburgh was dirty. Smoke from the mills hung over the region’s river valleys, and waste (human, animal, and industrial) fouled the rivers. By the turn of the twentieth century, Pittsburgh’s social and environmental issues were so well known that the Russell Sage Foundation chose it as the site for a major social science survey. The title of Maurine E. Greenwald and Margo Anderson’s 1996 edited collection, Pittsburgh Surveyed, alludes to this milestone; the book offers an excellent introduction to some of the large-scale changes and personalities that shaped industrial Pittsburgh’s development, building on the now iconic edited collection City at the Point (1989) and Roy Lubove’s seminal Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh (1969).[5]

How Pittsburghers attempted to understand and manage the environmental consequences of industrialization has been fertile ground for historical scholarship on technology and the urban environment and urban planning, notably by Joel A. Tarr and Edward K. Muller, whose collected and individual works offer an excellent window into the unique (and often similar stories) of infrastructure development and planning in Pittsburgh.[6] Moreover, both Tarr and Muller mentored generations of PhD students (including both authors) who have gone on to write about a range of Pittsburgh-related topics. More recently, scholarship on the city’s philanthropic history has illuminated other legacies of the industrial and post-industrial era through the lens of individual and organizational giving.[7]

This short overview does not fully do justice the full arc of the story of industrial Pittsburgh. And while the Pittsburgh story is often unique, much of it is also shared by many other midwestern cities that also grew on the back of heavy industry, saw substantial immigration, and eventually declined as the demand for industrial products waned and the environmental and costs to produce steel mounted after World War II.

Post-Industrial Pittsburgh

Since the 1980s and the collapse of steel, the story of post-industrial Pittsburgh has gained national attention. Often this transition has been held up as yet another successful version of “Renaissance” for a city that saw substantial elite-driven renewal actions over the second half of the twentieth century.[8] This popular narrative overlooks inequities in housing markets, access to employment, and health outcomes that still exist in Pittsburgh. Instead, it chooses to focus on the industry-turned-tech narrative that prioritizes the actions of universities, not-for-profit health care systems, and private-sector entrepreneurs. Fortunately, urban historians (who are often skeptical of glowing positive narratives) have introduced some necessary complexity. In fact, Roy Lubove started to tell this story even as Pittsburgh’s collapse was unfolding around him in Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh Volume Two, published in 1996.[9] More recently, Tracy Neumann’s Remaking the Rust Belt, Allen Dieterich-Ward’s Beyond Rust, and Aaron Cowan’s A Nice Place to Visit, offer readers comparative and regional accounts of Pittsburgh’s postwar transformation.[10]

After World War II, a series of biomedical successes, including the Salk polio vaccine and pioneering work in liver transplantation by Dr. Thomas Starzl, made Pittsburgh a destination for patients, physicians, and scientists—which is a story that Andrew Simpson tells in his 2019 book, The Medical Metropolis.[11] By 2008 academic medicine had become so central to modern Pittsburgh that the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, after relocating its headquarters to the U.S. Steel Tower, placed its logo atop what is the city’s tallest building.

But not all Pittsburghers have shared equally in a medical economy, as Gabriel Winant demonstrates in his 2021 book The Next Shift. The inequity in wages and health outcomes that has marked the care economy raises important questions about what this means for the future of Pittsburgh and other cities that have increasingly come to rely on a medical service sector for economic survival.[12] In addition to a growing health care sector, corporate and academic science has historically (and in the present) also been seen by regional elites as another engine of economic transition. This was fueled by changes in patent law, growing federal support for science in area universities, Cold War defense spending, and legacy corporations like Gulf Oil and Westinghouse.

The idea that Pittsburgh’s economy should skew heavily in the direction of diverse technology and advanced manufacturing was most visible during the collapse of steel in the 1980s, as regional leaders in government and of the Allegheny Conference on Community Development promoted Pittsburgh as a global technology hub by publishing the Strategy 21 Report and working with state and federal officials to build new spaces for scientific research and university-industry partnerships.[13] Patrick Vitale, in his 2021 Nuclear Suburbs, shows how central the science economy was to Pittsburgh and how it contributed to some of the inequity we see in our region today.[14] A focus on technology and urban development offers new possibilities for thinking about similar medical- and science-focused efforts in other Rust Belt cities.[15]

Pittsburgh’s struggle for civil rights and economic justice is inextricably tied to the history of urban renewal and neighborhood change, as historians like Joe W. Trotter, Jared N. Day, and Jessica D. Klanderud show.[16] The city has a long legacy of treating African Americans as second-class citizens, easily displaced and marginalized. That the city’s Black neighborhoods have survived over the past century is a testament to the community’s resiliency. But it did not occur without substantial hurdles. Many African Americans who arrived in Pittsburgh during the Great Migration found significant barriers to occupational and housing mobility that European immigrants overcame, thus creating what Laurence Glasco calls twin “burdens” of economy and geography.[17] Moreover, as the home of the Pittsburgh Courier and as a center for Negro League baseball, with teams like the Pittsburgh Crawfords and Homestead Grays, Pittsburgh has long been a center of civil rights activism that cuts across class lines, as demonstrated by the scholarship of Rob Ruck, Adam Lee Cilli, and Pamela Walck, among others.[18]

Redlining maps from the 1930s illustrate the difficulty African Americans faced in obtaining bank loans to buy or fix up houses.[19] Black migrants who came to Pittsburgh to work in its many steel mills during the Great Migration found constant barriers to decent housing. “Within racially segregated residential areas,” writes Peter Gottlieb, “the migrants formed enclaves, occupying the most dilapidated, poorly equipped, unsanitary structures.”[20] After World War II, the city’s Renaissance program devastated Black communities through massive displacement, social upheaval, and few new employment opportunities, a phenomenon Mindy Thompson Fullilove named “root shock.”[21]

The disruption of urban renewal came to a head as violence exploded in many Black neighborhoods upon Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968.[22] Yet, resistance to top-down solutions took other, more productive forms, as some African American neighborhoods created community development corporations and embraced historic preservation.[23] In the late 1980s, an anti-redlining movement encouraged more public and private investment in underserved areas.[24] However, despite much progress since that time to de-concentrate poverty and increase investment into low-income and African American neighborhoods, redlining and segregation persist as the scourge of gentrification threatens to unravel many of the gains made over the past two decades.[25]

Today at 69,050 people, Pittsburgh’s Black population is at its lowest level since the 1930s. Demographic figures indicate the greatest percentage decline in the African American population over the past decade (down 13 percent) since the 1850s, the latter attributed to the Fugitive Slave Act.[26] Absent intentional efforts to build generational wealth among African Americans, it is not clear that future community development efforts will ameliorate long-term racial inequalities.[27]

Where Do We Go From Here?

Just over two decades into the twenty-first century, Pittsburgh looks forward to the future. So when you join us for the 2023 Urban History Association Meeting, we hope you get out into the city and region and explore some of the places where Pittsburgh’s historical legacy and post-industrial present and future come together.

Take, for example, the Lower Hill District neighborhood, a low- to moderate-income neighborhood located only blocks from Downtown. A storied African American community, once compared to Harlem of the 1930s and 1940s, in the 1950s and 1960s it became the site of major urban renewal projects, including a Civic Arena, which by the late 1960s became the home to the Pittsburgh Penguins hockey franchise. Today the area is once again filled with the sounds of construction. While the Civic Arena is long gone, a new project is arising on the site where it once stood. Here the goal is to create mixed-use and mixed-income commercial and residential space that connects the Hill District with downtown while also providing restorative justice for previous mid-century urban renewal efforts.[28]

Across the Monongahela River, the land that was once home to the Jones & Laughlin Steel Works and the U.S. Steel Works at Homestead is now shopping and entertainment centers. If you leave the city of Pittsburgh, you can visit Rankin, where the legacy of iron and steel is preserved at the Carrie Furnaces. But for every reconversion of a steel site or opening or expansion of a new hospital or university research laboratory, much of our region has not experienced the type of substantive post-industrial transformation that yields equity, prosperity, and a better future for all Pittsburghers. We hope that your visit and the stories that urban historians of the Pittsburgh region have told might offer some lessons for understanding and shaping change in your own communities.

Selected Monographs of Potential Interest

With thanks to David Grinnell, Coordinator of Archives and Manuscripts, Archives and Special Collections, University of Pittsburgh Library System.

2023

Klanderud, Jessica D. Struggle for the Street: Social Networks and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Pittsburgh. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming April 2023.

2022

King, Maxwell and Louise Lippincott. American Workman: The Life and Art of John Kane. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022.

Pitz, Marylynne and Laura Malt Schneiderman. Kaufmann’s The Family that Built Pittsburgh’s Famed Department Store. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2022.

2021

Cilli, Adam Lee. Canaan, Dim and Far: Black Reformers and the Pursuit of Citizenship in Pittsburgh, 1915-1945. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2021.

Buechel, Kathleen W., ed. A Gift of Belief: Philanthropy and the Forging of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021.

Vitale, Patrick. Nuclear Suburbs: Cold War Technoscience and the Pittsburgh Renaissance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021.

Winant, Gabriel. The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021.

2020

Gilmore, Peter E. Irish Presbyterians and the Shaping of Western Pennsylvania, 1770-1830. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020.

McConnell, Michael N. To Risk It All: General Forbes, the Capture of Fort Duquesne, and the Course of Empire in The Ohio Country. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020.

McDevitt, Cody. Banished from Johnstown: Racist Backlash in Pennsylvania. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2020.

Oppenheimer, Mark. Squirrel Hill: The Tree of Life Synagogue Shooting and the Soul of a Neighborhood. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2021.

Trotter, Joe William, Jr. Pittsburgh and the Urban League Movement: A Century of Social Service and Activism. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 2020.

2019

Muller, Edward K. and Joel A. Tarr, eds. Making Industrial Pittsburgh Modern: Environment, Landscape, Transportation, Energy, and Planning. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019.

Simpson, Andrew T. The Medical Metropolis: Health Care and Urban Transformation in Pittsburgh and Houston. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019.

2018

Whitaker, Mark. Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

2016

Cowan, Aaron. A Nice Place to Visit: Tourism and Urban Revitalization in the Postwar Rustbelt. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2016.

Dieterich-Ward, Allen. Beyond Rust: Metropolitan Pittsburgh and the Fate of Industrial America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Neumann, Tracy. Remaking the Rust Belt: The Postindustrial Transformation of North America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016.

Stoddard, Evan. Transformed: Reinventing Pittsburgh’s Industrial Sites for A New Century, 1975-1995. Pittsburgh: Harmony Street Publishers, 2016.

2015

O’Neil, Gerard F. Pittsburgh Irish: Erin on the Three Rivers. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015.

2014

Aurand, Martin. The Spectator and the Topographical City. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014.

Bamberg, Angelique. Chatham Village: Pittsburgh’s Garden City. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014.

Rooney, Dan and Carol Peterson. Allegheny City: A History of Pittsburgh’s Northside. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014.

2013

Barcousky, Len. Civil War Pittsburgh: Forge of the Union. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2013.

2012

Ramey, Jessie B. Child Care in Black and White: Working Parents and the History of Orphanages. Champaign-Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

2011

Finley, Cheryl, Laurence Glasco, and Joe Trotter. Teenie Harris, Photographer: Image, Memory, History. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press/Carnegie Museum of Art, 2011.

Mellon, James. The Judge: A Life of Thomas Mellon, Founder of a Fortune. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Rishel, Joseph F. Pittsburgh Remembers World War II. Charleston SC: The History Press, 2011.

Dietrich, William S., II. Eminent Pittsburghers: Profiles of the City’s Founding Industrialists. Lanham, MD: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2011.

2010

Glasco, Laurence. The WPA History of the Negro in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010.

Ruck, Rob L., Maggie Jones Patterson, and Michael P. Weber. Rooney: A Sporting Life. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

Trotter, Joe W. and Jared N. Day. Race and Renaissance: African Americans in Pittsburgh since World War II. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010.

Other Books of Potential Interest

Baldwin, Leland D. Pittsburgh: The Story of a City, 1750-1865. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1937, 1970.

Bauman, John F. and Edward K. Muller. Before Renaissance: Planning in Pittsburgh, 1889-1943. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006.

Bodnar, John, Roger Simon, and Michael P. Weber. Lives of Their Own: Blacks, Italians, and Poles in Pittsburgh, 1900-1960. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983.

Burstin, Barbara. Steel City Jews. Apollo, PA: Closson Press, 2008.

Conner, Lynne Thompson. Pittsburgh in Stages: Two Hundred Years of Theater. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007.

Couvares, Francis G. The Remaking of Pittsburgh: Class and Culture in an Industrializing City, 1877-1919. Albany: The State University of New York Press, 1984.

Crouch, Stanley. One Shot Harris: The Photographs of Charles “Teenie” Harris. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 2002.

Crowley, Gregory J. The Politics of Place: Contentious Urban Redevelopment in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005.

Fox, Arthur B. Pittsburgh During the American Civil War, 1860-1965. Chicora, PA: Mechling Bookbindery, 2002.

Fullilove, Mindy Thompson. Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It. New York: Ballantine Books, 2005.

Greenwald, Maurine W. and Margo Anderson, eds. Pittsburgh Surveyed: Social Science and Social Reform in the Early Twentieth Century. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996.

Hinshaw, John. Steel and Steelworkers: Race and Class Struggle in Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002.

Hays, Samuel P., ed. City at the Point: Essays on the Social History of Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989.

Lorant, Stefan. Pittsburgh: The Story of An American City. Pittsburgh: Esselmont Books, 1999.

Lubove Roy. Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh: Government, Business, and Environmental Change. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1969; as Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh Volume One, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996.

Lubove Roy. Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh Volume Two: The Post-Steel Era. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996.

Mellon, Steve. After the Smoke Clears: Struggling to Get By in Rust Belt America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006.

Modell, Judith. A Town Without Steel: Envisioning Homestead. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1998.

Powers, Tom and James Wudarczyk. Allegheny Arsenal Handbook. Pittsburgh: The Lawrenceville Historical Society, 2022.

Rishel, Joseph F. Founding Families: The Evolution of A Regional Elite, 1760-1910. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005.

Ruck, Rob. Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993.

Toker, Franklin. Pittsburgh: An Urban Portrait. University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1987.

Toker, Franklin. Pittsburgh: A New Portrait. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2009.

Toker, Franklin. Buildings of Pittsburgh. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2000.

Toker, Franklin. Fallingwater Rising: Frank Lloyd Wright, E.J. Kaufmann, and America’s Most Extraordinary House. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2003.

Scarpaci, Joseph L. and Kevin J. Patrick, eds. Pittsburgh and the Appalachians: Cultural and Natural Resources in a Postindustrial Age. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006.

Tarr, Joel A., ed. Devastation and Renewal: An Environmental History of Pittsburgh and its Region. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005.

Warren, Kenneth. Triumphant Capitalism: Henry Clay Frick and the Industrial Transformation of America. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996.

Warren, Kenneth. Big Steel: The First Century of the United States Steel Corporation 1901-2001. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2001.

Weber, Michael P. Don’t Call Me Boss: David L. Lawrence, Pittsburgh’s Renaissance Mayor. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006.

Weber, Michael P. and Peter N. Stearns. The Spencers of Amberson Avenue. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1983.

Dan Holland is an adjunct professor of history at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. A Pittsburgh native, Dan founded the Young Preservationists Association of Pittsburgh and has held leadership positions at local, regional, and national community reinvestment organizations. He specializes in American history, history of Pittsburgh, nonprofit management, historic preservation, and community reinvestment. Dan authored numerous studies on financial institution lending in Pittsburgh as well as others regarding African American history in Pittsburgh, historic preservation, and the impact of mid-century urban renewal upon minority communities. His latest publication is a book chapter entitled, “Narratives of Resistance in Lyon and Pittsburgh,” in Constructing Narratives for City Governance, published in Cheltenham, United Kingdom, by Edward Elgar Publishing (2022).

Andrew T. Simpson is an Associate Professor of History at Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His book, Making the Medical Metropolis: Health Care and Economic Transformation in Pittsburgh and Houston (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019), examines the relationship between cities and not-for-profit health care in the late twentieth-century United States. He is currently working on a new research project examining the history of aging in the United States.

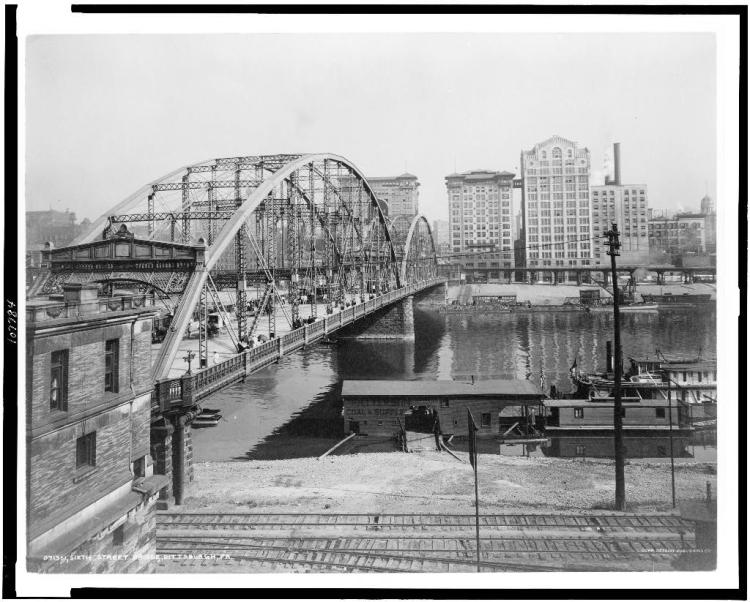

Featured image (at top): Sixth Street Bridge, Pittsburgh, between 1898 and 1915. Detroit Publishing Co., Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

[1] For more on the HQ2 proposal see https://pghq2.net. See also Patrick Doyle, Margaret J. Krauss, Kathleen J. Davis, “Pittsburgh Among Top 20 Amazon HQ2 Finalists,” 90.5 WESA, Jan. 18, 2018, https://www.wesa.fm/development-transportation/2018-01-18/pittsburgh-among-top-20-amazon-hq2-finalists.

[2] This critique has been made by several historians including Patrick Vitale in “The Pittsburgh Fairy Tale” Jacobin, June 20, 2017, https://jacobin.com/2017/06/pittsburgh-tech-new-economy-manufacturing-inequality.

[3] Frances G. Couvares, The Remaking of Pittsburgh: Class and Culture in an Industrializing City (Albany: The State University of New York Press, 1984), 10. For more on Pittsburgh’s founding families and industrial leaders see Joseph F. Rishel, Founding Families: The Evolution of A Regional Elite, 1760-1910 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005) and William S. Dietrich II, Eminent Pittsburghers: Profiles of the City’s Founding Industrialists (Lanham, MD: Taylor Trade Publishing, 2011).

[4] For some examples about the history of the steel industry see the work of Kenneth Warren. Recent work on policing and organized crime has also deepened our understanding of industrial and post-industrial Pittsburgh and the region. See Elaine S. Frantz, “The Homestead Strike and the Weakening of the First US National Paramilitary System” The Global South 12, no. 2 (Fall 2018): 45-63 and Jeanine Mazak-Kahne, “Small-Town Mafia:’ Organized Crime in New Kensington, Pennsylvania,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 78, no. 4 (Autumn 2011): 355-392.

[5] Maurine W. Greenwald and Margo Anderson, eds., Pittsburgh Surveyed: Social Science and Social Reform in the Early Twentieth Century (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996); Samuel P. Hays, ed., City at the Point: Essays on the Social History of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1989); Roy Lubove, Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh: Government, Business, and Environmental Change (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1969). The University of Pittsburgh Press has made their back catalog available digitally for free. See https://digital.library.pitt.edu/collection/university-pittsburgh-press-digital-editions. Much of the Pittsburgh story is also told through the work of museums and historic preservation organizations including: the Senator John Heinz History Center, which publishes Western Pennsylvania History Magazine; Rivers of Steel, and the Battle of Homestead Foundation, which published Charles McCollester’s The Point of Pittsburgh: Production and Struggle at the Forks of the Ohio in 2008.

[6] For examples see Joel A. Tarr, ed., Devastation and Renewal: An Environmental History of Pittsburgh and its Region (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005); John F. Bauman and Edward K. Muller, Before Renaissance: Planning in Pittsburgh, 1889-1943 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006); Edward K. Muller and Joel A. Tarr, eds., Making Industrial Pittsburgh Modern: Environment, Landscape, Transportation, Energy, and Planning (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2019).

[7] Kathleen W. Buechel, ed., A Gift of Belief: Philanthropy and the Forging of Pittsburgh (Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2021).

[8] For scholarship complicating the Pittsburgh Renaissance, see the forum coordinated by Edward K. Muller in the Journal of Urban History 41, no. 1 (Jan. 2015).

[9] Roy Lubove, Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh Volume Two: The Post-Steel Era (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996).

[10] Tracy Neumann, Remaking the Rust Belt: The Postindustrial Transformation of North America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016); Allen Dieterich-Ward, Beyond Rust: Metropolitan Pittsburgh and the Fate of Industrial America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016); Aaron Cowan, A Nice Place to Visit: Tourism and Urban Revitalization in the Postwar Rustbelt (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2016).

[11] Andrew T. Simpson, The Medical Metropolis: Health Care and Economic Transformation in Pittsburgh and Houston (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2019).

[12]Gabriel Winant, The Next Shift: The Fall of Industry and the Rise of Health Care in Rust Belt America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021).

[13] See, for example, Robert E. Gleeson’s chapter “New Forms of Philanthropy” in Buechel, A Gift of Belief; Evan Stoddard, Transformed: Reinventing Pittsburgh’s Industrial Sites for A New Century, 1975-1995 (Pittsburgh: Harmony Street Publishers, 2016); and Simpson, The Medical Metropolis, chapter 4.

[14] Patrick Vitale, Nuclear Suburbs: Cold War Technoscience and the Pittsburgh Renaissance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2021).

[15] Guian McKee, Hospital City, Health Care Nation: Race, Capital, and the Costs of American Health Care (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, forthcoming April 2023).

[16] Joe W. Trotter and Jared N. Day, Race and Renaissance: African Americans in Pittsburgh since World War II (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010) and Jessica D. Klanderud, Struggle for the Street: Social Networks and the Struggle for Civil Rights in Pittsburgh (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, forthcoming April 2023).

[17] According to Laurence Glasco, “Taken together, the historical materials indicate that, in addition to suffering the same racial discrimination as their counterparts elsewhere, blacks here have borne two additional burdens. The first was economic. The stagnation and decline of Pittsburgh’s steel industry began just after World War I—well before that of most Northern cities—and very early closed off opportunities for black economic progress. The second burden was geographic. Whereas the flat terrain of most Northern cities concentrated blacks into one or two large, homogeneous communities, Pittsburgh’s hilly topography isolated them in six or seven neighborhoods, undermining their political and organizational strength.” Laurence Glasco, “Double Burden: The Black Experience in Pittsburgh,” in City at the Point, 70. As Bodnar, Simon, and Weber write, “historians have suggested that the earlier immigrants benefited from the pervasive racism of society and advanced occupationally and socially in American cities only at the expense of blacks.” John Bodnar, Roger Simon, and Michael P. Weber, Lives of Their Own: Blacks Italians, and Poles in Pittsburgh, 1900-1960 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983), 5.

[18] Rob Ruck, Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993) and Pamela Walck, Voices of the Pittsburgh Courier: Mrs. Jessie Vann and the Men and Women of America’s ‘Best’ Weekly (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, forthcoming).

[19] University of Richmond, “Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America” https://dsl.richmond.edu/panorama/redlining/#loc=5/39.1/-94.58.

[20] Peter Gottlieb, Making Their Own Way: Southern Blacks’ Migration to Pittsburgh, 1916-1930 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987), 66. See also John Hinshaw, Steel and Steelworkers: Race and Class Struggle in Twentieth-Century Pittsburgh (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002) and Mark Whitaker, Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018).

[21] Mindy Thompson Fullilove, Root Shock: How Tearing Up City Neighborhoods Hurts America, and What We Can Do About It (New York: Ballantine Books, 2004).

[22] Dan Holland, “Pittsburgh’s Urban Renewal: Industrial Park Development, Freeway Construction, and the Rise of the Civil Rights Movement,” Pennsylvania History: A Journal of Mid-Atlantic Studies 89, no. 2 (Spring 2022): 163-193, https://doi.org/10.5325/pennhistory.89.2.0163. See also Alyssa Ribeiro, “’A Period of Turmoil’: Pittsburgh’s April 1968 Riots and Their Aftermath” Journal of Urban History 39, no.2 (Mar. 2013): 147-171, https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144211435123.

[23] See chapter 5 on “Pittsburgh: Partnerships, Preservation, and the CRA” in Elise M. Bright, Reviving America’s Forgotten Neighborhoods: An Investigation of Inner City Revitalization Efforts (New York: Routledge, 2003).

[24] Bright, chapter 5, Reviving America’s Forgotten Neighborhoods.

[25] Dan Holland and Gregory Squires, “Community Reinvestment Challenges in the Age of Gentrification: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania as a Case Study for Wide Bank Lending Disparities,” Community Development Journal, August 2022, https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsac022. See also Devin Q. Rutan and Michael R. Glass, “The Lingering Effects ofNeighborhood Appraisal: Evaluating Redlining’s Legacy in Pittsburgh,” The Professional Geographer 70, no. 3 (Oct. 2017): 339-349, https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2017.1371610.

[26] Glasco, “Double Burden,” 72.

[27] See Ralph Bangs, “Pittsburgh’s Deplorable Black Living Conditions,” unpublished study, University of Pittsburgh, Feb. 23, 2021, and Sabina Deitrick and Christopher Briem “Quality of life and demographic-racial dimensions of differences in most livable Pittsburgh,” Journal of Urban Regeneration and Renewal 15, no. 2 (Winter 2022).

[28] See the website created by commercial real estate company Jones Lang LaSalle at https://www.lowerhillredevelopment.com and the Hill District Master Plan at the City of Pittsburgh’s Urban Redevelopment Authority’s Website at https://www.ura.org/pages/lower-hill.