The Metropole Bookshelf is an opportunity for authors of forthcoming or recently published books to let the UHA community know about their new work in the field.

by Mike Amezcua

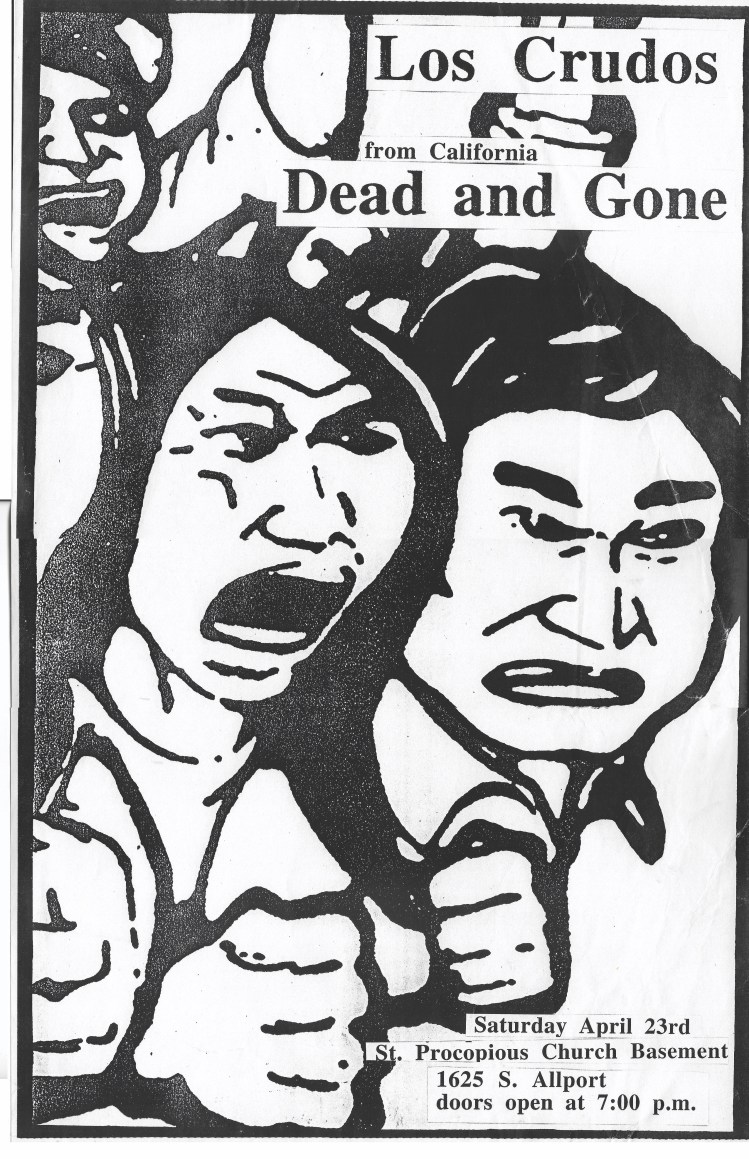

Punk fliers are planning documents. Not the official kind produced by city planning departments, of course, nor the grassroots plans by neighborhood activists resisting investment capital and gentrification. But these fliers contain a planning schema all the same, creatively interpolating the built environment for the staging of DIY shows and consciousness-raising.

During the 1990s, those who came across a flier for a hardcore show in Chicago’s Pilsen neighborhood were most likely introduced to Los Crudos—the community’s most important hardcore punk band—and to a generative local youth culture that bridged music and social issues. Punk fliers directed attendees to go to addresses and otherwise familiar coordinates in the neighborhood: a corner store, a family’s basement, a cultural center where punk shows were held. Instructions were given: enter through the side door of a church’s basement, find the empty warehouse near the railway viaduct, show up to the laundromat at a certain time. What attendees found were bands performing immensely fast and loudly amplified music. Neighborhood punk shows in the predominantly Mexican, working class neighborhood utilized commercial, residential, and community spaces for exchange, forums, and awareness-raising for issues affecting the local community—immigration hostilities, gang violence, housing insecurity, and gentrification. In short, these “plans” directed observers and congregants not only to where the music was happening but, more importantly, to enter into an unanchored urban commons for the distribution of information, education, and action.

It might be helpful to briefly describe the history of hardcore punk and Los Crudos’s place in this history. To be sure, by the start of the 1990s when Los Crudos began, punk was an “old” genre by many metrics, having turned mainstream since its initial grittier underground emergence in the late 1970s. The more aggressive hardcore scenes that arose across the United States in the early 1980s offered plenty of teenage angst, biting social commentary, and empowered countless youth to involve themselves in do-it-yourself projects through music, forming bands, starting independent record labels, and making zines. But hardcore’s resonance waned by the start of the George H. W. Bush years, and the music hardly carried the fire and urgency of the earlier Ronald Reagan era. That is, until Los Crudos emerged in 1991. In the face of the corporatization of punk rock and a Caucasian-centric hardcore scene, the all-Latino hardcore band from Pilsen arose to scream about issues where previously there had been silence. Los Crudos opted to sing in Spanish to connect with the communities they came from in Mexican Chicago. They sang about Latinos/as and Latin America from the point of view of immigrants, the working class, the abused, and the marginalized. In the process, they created a space for Latino youth to feel that DIY punk and hardcore was for them, too. Los Crudos’s sole anthem in English was called “That’s Right Motherfuckers We’re That Spic Band,” an ode to doubling-down on—or perhaps reclaiming—the otherness they represented when they played outside of their communities. Despite the somewhat racial and ethnic diversity that existed in the punk world since its beginnings, no other band was amplifying the Latino/a/x experience through punk the way Los Crudos did. Period. Full stop.

Los Crudos and other Latino punk and hardcore youth from the predominantly Mexican communities of Pilsen and Little Village in Chicago made a concerted effort to organize do-it-yourself punk and hardcore shows in the thick of an immigrant, Spanish-speaking, working-class area. It was a rejection of the big-name rock clubs in favor of locality and community. Punk and hardcore were hardly the typical soundtrack of Pilsen, but Latino youth felt it crucial that punk be retooled in the service of their community to reflect on the political economy and deindustrial conditions in their neighborhoods that made them more vulnerable to displacement.

The band also made critical spatial interventions in their home base of Mexican Pilsen. Subverting the built environment, they set up shows in neighbors’ basements, church social halls, laundromats, community centers, and business storefronts. Latino punk youth also enlisted themselves in the battleground over community planning—and its takeover by neoliberal forces—by raising the alarm on these issues during shows, and doing so in the plainest of language. They valued urban makeshift spaces as a community resource, not part of an individual’s profit scheme. Punk fliers or “plans” offered a cartography of subversion that reexamined built spaces, their uses, and their utilization for the crafting of new messages about empowerment, disenfranchisement, and systemic critiques. Punk shows turned into discussions about real estate speculators, harmful city policies, and the corporate hands that were planning to remake Pilsen for profit. “Apartment buildings which have been transformed have not only been carefully sculpted,” Martin Sorrondeguy, vocalist for Los Crudos, wrote in fliers he handed out at shows during this era, “they have also been given something similar to an enema…in this case flushing people out from their homes.”

While researching and writing Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to the Age of Gentrification, I knew I couldn’t ignore the contributions that Latino punks made to the corpus of grassroots spatial critique on exclusionary redevelopment. As a former participant myself in the Southern California DIY punk and hardcore subculture of the 1990s and early 2000s, I took a page from my own punk roots to view urban history through the lens of Latino punk youth and their visions for an autonomous and unbowed Mexican Chicago.

Pilsen had long been both a target of private redevelopment schemes that threatened the displacement of long-time working-class families and a target of the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service agents) for its significant presence of undocumented residents. Within this local context, Los Crudos innovated a brazen defense of the undocumented in their powerful band motto, “Ilegal y Qué?” (“Illegal and What?”), often seen screenprinted on shirts and patches. The band members consisted of immigrants and the children of immigrants, some even undocumented. Martin Sorrondeguy, Crudos’s beloved singer, grew up hearing stories from his Uruguayan family about life under a military dictatorship. Guitarist José Casas, whose parents were Mexican immigrants, recalled his family being displaced by urban renewal. One of Los Crudos’s songs from 1995, “No Me Vengan a Salvar” (“Don’t come to save me”), carried an important double meaning that resonated in immigrant Pilsen. It made a nod to the long history of US military interventions across the Americas and its benevolent signaling of “bringing democracy” to other nations. It also carried a localized message that could apply to Pilsen and its supposed “salvation” by the corporate philanthropy that guided uneven community development in the 1980s and 1990s.

In writing Making Mexican Chicago, I realized that punk and Latino urban history intersected much more than I initially thought. A decade before Los Crudos was performing in Pilsen’s basements and laundromats and delivering critiques about neoliberal gentrification to the audience, advocacy planners and architects working in the Eighteenth Street Development Corporation (ESDC) were in the throes of trying to revitalize Pilsen for low-income residents, hoping to overturn decades of disinvestment. The ESDC was a nonprofit organization, a product of the 1970s community control battles against lenders and insurance companies who discriminated against poor communities of color. In the Reagan era, the ESDC traded direct action campaigns for board member meetings and corporate grants to fund their projects. The ESDC’s mission was to renovate old housing, build new housing on vacant lots, provide new jobs in the building trades for teenagers, and revive commercial activity. In Pilsen the ESDC’s work was welcomed, and they managed to obtain ownership of dozens of blighted buildings and train Latino youth in carpentry, masonry, and bricklaying.

But the housing precarity experienced in 1980s Pilsen exceeded the resources provided by one nonprofit. Amidst an alarmingly high unemployment rate (above 21 percent in 1987) and spiking rent hikes by absentee landlords (many suburbanites “invested” in Pilsen as owners and profited off Latino renters), a climate of fear existed due to regular deportation sweeps made by the INS. While it brought some buildings back into the possession of working-class Mexican residents, the ESDC’s scope proved too narrow and its position too compromised in its entanglements with private foundation money to institute a larger plan for the stabilization of Mexican Pilsen. In 1989 a former director of the ESDC wrote of “foreboding things to come”—a time when Pilsen would be a Mexican community no longer. “[The] greedy hucksters,” he wrote, “they picked up buildings like grapes during the proverbial harvest. Knowing all the ropes, they acquired empty lots and tax delinquent properties from the poor Mexicans.”

In the mid-1990s Los Crudos took residence in an apartment building once saved by the ESDC from purchase by outside speculators. Its basement and first floor had been converted into an art gallery and community center called Calles y Sueños (“Streets and Dreams”), a far cry from the yuppy loft conversions that occurred to other buildings the ESDC was unable to get its hands on. It was here that Los Crudos rehearsed, prepared for tours, and collaborated with community members on an array of benefit projects against displacement and abuse of immigrants. Perhaps one of the most enduring initiatives that emerged from these collaborations was alerting residents to the hidden consequences behind city policies like Tax Increment Financing (TIF) that began in 1994, a measure designed to promote private development of housing in low-income areas like Pilsen. Members of Los Crudos and dozens of local artists associated with Calles y Sueños warned that this time displacement of residents would not come by way of the federal bulldozer but by bankers and speculators invited in by TIF to build and profit off of vacant lots. In local gatherings they demonstrated that these neoliberal policies were being pushed not only by the mayor and the bankers, but even by the alderman who was elected to represent the community. In one apartment building, two different camps of anti-displacement activism, only a few years apart, fought for alternatives. Pilsen punks made significant contributions to advocating, using, and defending local resources in the built environment, challenging the expertise of city officials, and while their imprint on the spaces they inhabited has been erased by gentrification, their music and fliers remind us of their defiant defense of their community

Mike Amezcua is Assistant Professor of History at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. He teaches and researches in Latinx history, urban history, the built environment, racial inequality, politics, and immigration. He is the author of Making Mexican Chicago: From Postwar Settlement to the Age of Gentrification (University of Chicago Press, 2022). His writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Chicago Sun-Times, Teen Vogue, and Public Books. In 2020, Amezcua was the co-winner of the Arnold Hirsch Prize for Best Article in Urban History by the Urban History Association, and in 2021 he was named a Mellon Emerging Faculty Leader by the Institute for Citizens & Scholars.

Featured image (at top): Flier for hardcore punk show in basement of St. Procopius Church (1625 S. Allport Street) in Pilsen, Chicago, IL, April 23, 1994, Martin Sorrondeguy.