Fernandez, Johanna. The Young Lords: A Radical History. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

Reviewed by Leo Valdes

In 1969 activists convened at the first Chicano Youth Liberation Conference. Among them were New York Puerto Ricans excited to learn about a group of Chicago activists who wore purple berets and carried a Puerto Rican flag. But their excitement waned when conference organizers chose to exclude Black Americans from fully participating. “How can they say no to blacks? Some of us are obviously black,” recalled Iris Morales, future Young Lord Deputy Minister of Education. Chicanos based their decision on a “narrow interpretation of black nationalism’s race-based unity principle.” When the Puerto Rican contingent decided to leave, Corky Gonzalez broached a conversation, the decision was reversed, and a formal apology delivered by conference organizers. Such was the birth of the New York Young Lords, a Puerto Rican Black Power organization.

Brought to life by approximately one hundred oral histories, The Young Lords beautifully illustrates the rise and fall of a movement shaped by global economic restructuring and urban migrant life. Fernández uniquely draws on an extensive archive of personal papers, audio and visual recordings, press accounts, the Young Lords’ newspaper Palante, COINTELPRO documents, and, most importantly, the records from the Handschu files, a repository of one million NYPD surveillance records covering 1952-1972 (and only made public as result of her lawsuit). Her source base and meticulous research allows Fernández to make several important contributions to our understanding of late twentieth-century urban activism.

The Young Lords begins in Chicago where eleven-year-old Cha Cha Jiménez formed a street-fighting organization to defend against the white ethnic gangs who terrorized local Latinos and Black Americans. After discovering the Black Power movement in prison, Jiménez transformed his gang into a political organization modelled on the Black Panther Party. The Chicago Young Lords inspired the New York organization to which the rest of the book is devoted. Unlike their peers, however, New York Young Lords were mostly high school graduates and the first in their families to go to college. As the children of poor, rural families displaced by Operation Bootstrap, a postwar government program to “industrialize” Puerto Rico, they endured urban poverty, police violence, racism in schools, and the burden of laboring as language and cultural mediators for their island-born parents. Impressed with Cha Cha’s “solidarity with the black underclass,” they merged three different groups into the Young Lords Organization and asserted their alignment with the Black Power movement.

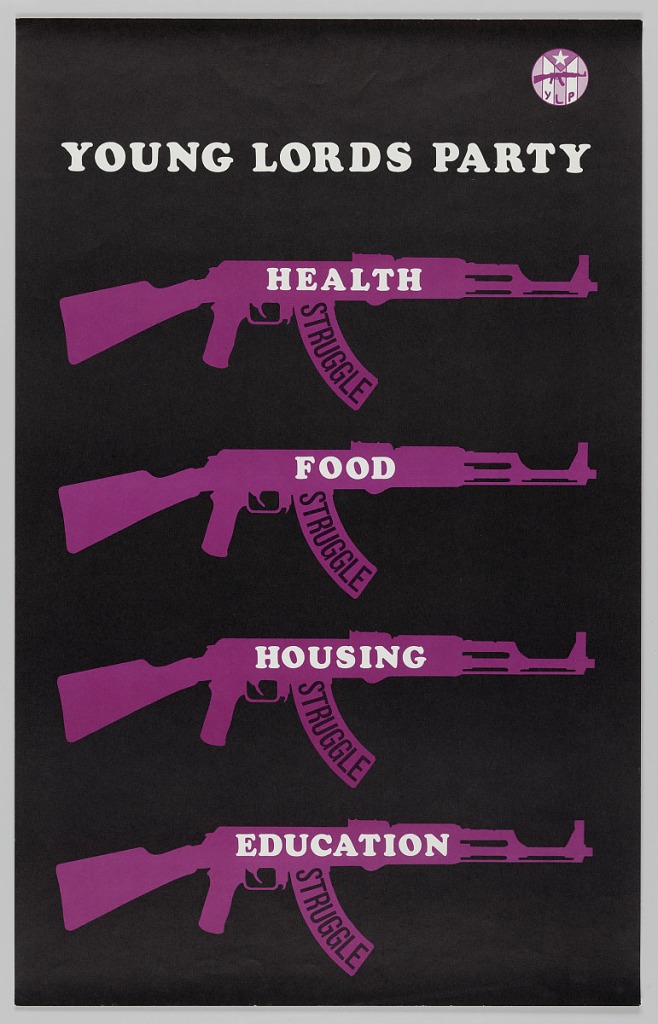

The book’s central chapters follow specific “offensives,” such as the Garbage Offensive, which involved thousands of local residents fighting for better sanitation services. The name was a nod to the 1968 Tet Offensive in Vietnam and, indeed, the Young Lords saw themselves as part of a global decolonial movement. Political education made up the core of their vision for liberation and providing social services the center of their activities. Though short-lived, the YLO claimed several victories, including the passage of anti-lead-poisoning legislation and the first municipal investigation into the prison conditions of the notorious NYC “Tombs.” Fernández attributes their decline to their failed expansion into Puerto Rico, the influence of new authoritarian members, and the designs of COINTELPRO which took advantage of a vulnerable moment as the organization grew.

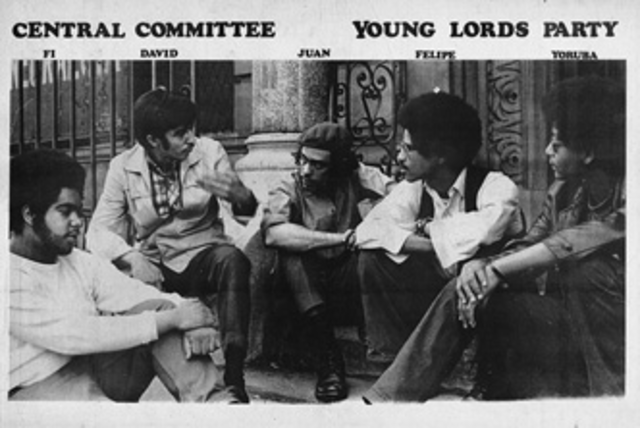

Typically imagined as having been “inspired” by the Black Power movement, Fernández argues that the Young Lords actually were a Black Power organization. Three of the five central committee members were Black Latinos, and twenty-five to thirty percent of the organization Black American.[1] As Young Lords Chairman and Afro-Puerto Rican Felipe Luciano stated, “Black and Puerto Ricans in New York—when you say the word, it already connotes a whole experience.” Moreover, her argument reflects her historical understanding of Black Power as a 1960s/70s expression of Black nationalism that “cohered” around the right to armed self-defense, Black pride, and building power independent of white society. Black Power appealed to many different ethnic and racial groups and inspired a range of solutions to racial oppression that could be applied as much to northern urban environments as to the colony of Puerto Rico itself. YLO’s embrace of Black Power broke with the politically conservative generation of leadership who came before them and who believed Puerto Ricans were better off distancing themselves from Black Americans. In doing so, they denounced anti-black racism in Puerto Rico, reclaimed their Afro-Taino roots, and revitalized interest in the suppressed independence movement.

Fernández skillfully weaves the evolution of the organization into broader historical developments while resisting the urge to idealize a group whose spectacular aesthetic belied significant internal contradictions. For example, while student leadership chose the lumpen proletariat as its social base, the majority of Puerto Ricans were workers who could not dedicate the “twenty-five hours a day” the Young Lords demanded. The final chapters and coda, titled “Beware of Movements,” offers a careful assessment of the competing Leninist and Maoist traditions in the Party. Self-described revolutionary nationalists, the Young Lords were among the first to embrace the term Latino to unify Latinx people on the basis of a shared experience with U.S. imperialism.[2] Perhaps most importantly, the Young Lords created a language and activist blueprint to fight back against what has become known as the “urban crisis.” Their struggles in hospitals, schools, prisons, housing, and neighborhoods “established standards of decency in city services for city dwellers that expanded the definition of the common good.” The Young Lords is both social history at its finest and a teaching tool for today’s activists, especially those who seek global transformation but organize from the “heart of empire.”

Leo Valdes is a PhD candidate in the History department at Rutgers. Valdes studies twentieth century African American and Latinx history and is working on a social and political history of trans liberation that centers Black American and Latinx trans people.

Featured image (at top): Members of the Central Committee of the Young Lords. Palante (Young Lords newspaper), 1970, Wikimedia Commons.

[1] This was due, in part, to a decline in the Black Panther Party chapter in New York at the same time the Young Lords Party began to grow. However, the point is that Black Panther Party members would likely not have joined an organization that they did not consider in alignment with their goals and vision. But as Young Lords Chairman Felipe Luciano recalled: “I grew up around blackness. I never saw it as foreign. I didn’t have one parent who was light… I’ve always seen blackness in my life, so I never saw it as anything else but gorgeous. My mother’s gorgeous to me. My father is gorgeous to me and negritude was always described to me in the most glowing terms.”

[2] In fact, 5 to 8 percent of the organization were non-Puerto Rican Latinxs, among them Cubans, Dominicans, Mexicans, Panamanians, and Colombians.

Thanks for this✊

LikeLike