Peeples, Scott. The Man of the Crowd: Edgar Allan Poe and the City. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Reviewed by Katherine J. Kim

That we still associate the name Edgar Allan Poe with torture, insanity, loneliness, perversity, drug abuse, and drunkenness is owing in part to one Rufus Griswold, rival and author of perhaps the most unreliable, malicious, and influential of Poe obituaries. Following the appearance of the obit, the damage to Poe’s reputation continued thanks again to Griswold, who became, quite incredibly, Poe’s literary executor. A Poe story in itself.

While the effort to correct Griswold and depict Poe more accurately has become something of a cottage industry, what sets Scott Peeples’s “compact biography” apart from other recent work is that it also concerns cities, specifically Richmond, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York, where Poe spent much of his life and which stirred his imagination.

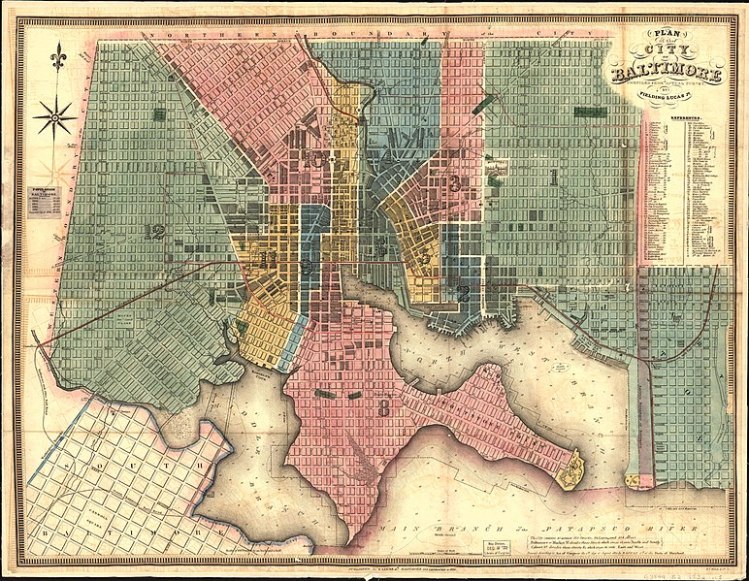

Peeples’s aim is to re-contextualize the image of Poe as a campy “nowhere man,” a brooding figure haunting the shadows of an isolated abode where we find a bottle of laudanum on the table, a ceaselessly thumping heart under the floorboards, and, circling overhead, a raven. In detailing Poe’s moves from city to city, Peeples presents an ambitious young man seeking to support his family and to establish himself as a writer, critic, and editor. No longer does Poe appear as an isolated loner. Peeples’s narrative is accompanied by archival maps and images as well as Michelle Van Parys’s photographs of Poe-related places, some creatively overlaid with images of what certain locations looked like closer to Poe’s time. In this account, readers see rapidly growing antebellum cities whose wealth supports the blooming literary scene in which Poe must engage to achieve literary success.

Poe was born to itinerant actors in Boston on January 19, 1809. After his father abandoned the family, his mother Eliza died, most likely of tuberculosis, two years later in Richmond. The two-year-old was then taken in by a wealthy couple, John and Frances Allan. Hence Edgar “Allan” Poe.

Though never formally adopted (a likely cause of tension over inheritance), Poe spent a comfortable youth in Richmond and London. Athletically and intellectually precocious, he was educated at various British and American schools. Though he may have carried himself as a gentleman, he was forced to abandon his studies at the University of Virginia because John Allan would not pay his college and gambling debts. Often broke and feeling unloved, he at times may well have seemed as uncertain and alienated as a one of his future characters.

Before Poe’s arrival in Baltimore, one of the cities with which he is most identified (its NFL team is the Ravens), Poe sojourned briefly in his hometown of Boston where, according to Peeples, he was “reborn.” There he published his first book Tamerlane and Other Poems “by a Bostonian” after enlisting as Edgar Perry and serving in 1827 at Boston Harbor’s Fort Independence. He then moved on to West Point where, despite being well regarded as a soldier and student, he got himself intentionally court-martialed.

Following the death of his beloved foster mother, and facing an increasingly hostile John Allan, Poe moved to Baltimore to stay with his aunt Maria Clemm and her family. With its fine harbor, strategically located between north and south, Baltimore’s flourishing commercial and manufacturing economy sustained libraries, bookstores, and various publications. Attempting to gain visibility, Poe entered and occasionally won writing contests, but what truly raised his stock in Baltimore’s literary scene was the publication of blistering reviews which gained him the moniker “Tomahawk Man.”

By the time he settled in Philadelphia in 1838, Poe was married to his thirteen-year-old cousin, Virginia Clemm, and continued to struggle with drink (which, contrary to popular belief, had more to do with his being a lightweight than his continually haunting liquor establishments). But it was here that he achieved a measure of artistic and professional success. As a magazine editor, he generated popular interest in secret writing, challenging readers to see if they could stump him by submitting indecipherable cryptograms. (Additionally, the plot of “The Gold-Bug,” written at this time, incorporates secret messaging.) Peeples suggests that Poe’s talent for decoding “would have been particularly associated with city life, which continually presented new phenomena to interpret, and where, according to conventional wisdom, appearances were nearly always deceiving.”

Poe was less concerned with the physical than the psychological aspects of the city. He was adept at depicting anxiety arising from living in proximity to—indeed sometimes under the same roof as—complete strangers. Peeples suggests that Poe’s stories respond “… to the mid-nineteenth-century city’s defining characteristics: alienation, ethnic diversity, racial tension, and the inscrutability of the urban landscape and its inhabitants.” It has been suggested that Poe endured rather than embraced city life, but the city is where he needed to be.

Poe lived in New York between 1844 and 1848. Like many New Yorkers, he moved frequently in search of cheaper lodging while also seeking to remain close to publishing houses. He continued to cherish the idea of establishing a literary journal; in the meantime, he maintained his reputation as a fearsome critic through a series of successful lectures attacking such beloved contemporaries as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. By 1847, Poe and his family had moved to the suburbs, the Fordham section of The Bronx, where it was hoped that fresher air would restore Virginia’s failing health. She died that year of tuberculosis. Along with other scholars, Peeples identifies Virginia’s death as a moment of deep despair followed by depression, failed romances, and increased itinerancy.

We should not allow Poe to depart from New York without recalling his brief stay in a farmhouse on West 84th Street, where he was writing a poem in which the central figure would be “a non-reasoning creature…” with the power of speech. Although he may well have been thinking of a common species of New Yorker, he more likely took inspiration from Dickens’s sagacious pet raven Grip (now housed in the Philadelphia Free Library) and the fictional raven in Barnaby Rudge. Happily, Poe settled on the raven, and what the bird delivered was the poem that rather quickly made Poe famous worldwide.

In the concluding chapter “In Transit (1848-1849),” Peeples depicts a desperate and ailing genius moving frenetically from one city to another, taking a final turn on the urban stage before his mysterious death in Baltimore. This chapter serves as a coda that allows us to review the cities where Poe once lived and which even now claim him as one of their own.

In contrast to most earlier works, The Man of the Crowd takes on slavery and racism more directly; Poe lived as a wealthy Southerner while with the Allans, and his association with slavery might make admirers somewhat uncomfortable. But what Peeples offers is a more nuanced understanding of the social, cultural, and physical lives of cities that shaped the work of “… arguably America’s first modern writer.” A brilliant stylist and critic, Poe is the widely acknowledged pioneer of detective, Gothic, and psychologically complex short fiction. His overarching influence ranges from Charles Baudelaire and Paul Valéry to Arthur Conan Doyle and H.G. Wells. After acknowledging Poe’s talent and faults, Peeples concludes with the image of a man shrouded in the mysteries that have intrigued readers since his enigmatic death. Poe lives in the city, forevermore!

Katherine J. Kim is Assistant Professor of English at Molloy College. She earned BA and MA degrees from the University of Chicago and a PhD from Boston College. She conceived of and co-organized the Edgar Allan Poe Bicentennial Celebration (held at BC) and participated in the creation of a Boston Public Library Poe exhibit and the installation of Boston’s Poe statue. Among other work, Katherine wrote book chapters for Kevin J. Hayes’s Edgar Allan Poe in Context and Philip Edward Phillips’s Poe and Place as well as articles published in Studies in the Novel, Sexuality and Culture, and Dickens Quarterly.

Featured image (at top): Fielding Lucas Jr., “Plan of the City of Baltimore,” (1836) Library of Congress.