By Seth Weitz

On January 16, 1989, Miami police officer William Lozano shot Black motorcyclist Clement Lloyd, killing both Lloyd and his passenger, Allen Blanchard. The shooting sparked several days of riots and brought to an end a tumultuous, but transformative, decade in Miami’s relatively short history. Dubbed the 1989 Miami Riots, they marked the third set of major riots to grip the city in ten years and highlighted the growing tensions in Miami. The narrative that was formed after the 1980 and 1982 Miami riots was that the University of Miami’s 1983 college football national championship and subsequent success in the 1980s helped to heal a racially divided city. A similar narrative surrounded the aftermath of the 1989 riots, as the Miami Heat and the Super Bowl helped bring calm and healing to some in a city that spent much of the decade in the international spotlight for the wrong reasons.

The 1980s were a profound decade for the city on many fronts. The metropolitan area’s population, starting at 2.2 million in 1970 and topping out at over 4 million in 1990, exploded over the course of twenty years. And, it was not just the numbers, it was the demographics.[1] The Mariel Boatlift in 1980 brought more than 125,000 Cubans to Miami, the largest civilian transport in history. Many middle-class, non-Hispanic whites in the community left the city, often referred to as the second “white flight,” the first occurring after the Brown v. Board decision in 1954. In 1960, Miami was 90 percent non-Hispanic white, but by 1990, it was only around 10 percent non-Hispanic white.[2] As the decade ended, Miami’s population was 391,000, of which 64 percent were listed as Hispanic, a vast jump from 1980. Black Miamians accounted for 25 percent of the city, while white non-Hispanics were a mere 11 percent.[3]

Miami police officer William Lozano’s actions on Martin Luther King Jr. Day in 1989 sparked civil unrest that tarnished the city’s image, but, more importantly, highlighted the frustration of its Black community. Lozano, according to police reports, had never been reprimanded. Both 23-year-old Clement Anthony Lloyd and his 24-year-old passenger Allan Blanchard were new to Miami, arriving from their native Virgin Islands only a few months earlier.[4] The shooting and the unrest that followed occurred within a week of Super Bowl XXIII, during which Miami had already drawn the world’s attention since the city was hosting the event.[5] There was fear that the game would be moved due to the racial disturbances, with Tampa mentioned as a possible landing site.

“Lloyd and his blood-red Kawasaki Ninja motorcycle were familiar figures in Overtown, and few paid much attention as he gunned it through neighborhood streets,” noted the New York Times. Neighbors and friends described him as an easy-going guy, with a “trademark grin,” who always wore a “blood red” helmet that matched his motorcycle.[6] As Lloyd and Blanchard were cruising through Overtown, a predominantly Black and underprivileged community near downtown Miami, officer Dawn Campbell and her partner William Lozano responded to a domestic dispute call at an apartment complex. After dealing with the incident, they were approached by a resident who reported a stolen license plate, and Lozano went to his trunk to get a report form. Not finding any, he picked up his radio to call other units to request the form.[7] According to police department spokesman Angelo Bitsis, “he [Lozano] heard the radio transmission and saw the direction. As the motorcycle approached him or went by him, Lozano fired his gun.”[8] The gunshot, having hit him the head, instantly killed Lloyd. The shooting caused the motorcycle to crash into an oncoming car, injuring the two passengers. While the two individuals from the automobile were released from the hospital the following day, Blanchard, Lloyd’s passenger on the motorcycle, died the next day from his injuries.[9]

Five Black witnesses in Overtown claimed that Lozano stepped out of his way, into the street, seemingly tracking Lloyd’s motorcycle for several seconds before firing the shots.[10] Others confirmed the story, with one observer concluding, “Lozano looked up, tossed his pen and notebook into his car’s open trunk and snatched his service weapon, a 9-millimeter automatic pistol, from his holster.” Another resident, who refused to be named for fear of police retribution, exclaimed, “he crouched, then kind of tiptoed out into the street. He crept into the street, almost to the center line, holding his pistol with both hands. Just when the motorcycle came by, he fired. Boom! He meant to kill him.” Allen Fordham confirmed the account, stating, “that’s exactly how it happened.” A ten-year-old, who was playing across the street at the time of the shooting, furthered, “I saw it. He held his gun up high and shot the guy when he went past.”[11] To many Black Miamians, this was another case of a Miami police officer using excessive force leading to death. White Miami differed, as many were more upset that the city was erupting in violence for the third time in nine years, further tarnishing the city’s image.

Witnesses said Lloyd’s body stayed in the street, his boots protruding from a white sheet, for more than two hours before the medical examiner arrived.[12] Within seconds, more than a hundred residents flocked to the scene, and almost immediately the crowd swelled to a couple hundred. Some of the crowd began pelting officers with rocks and bottles.[13] Despite in-person pleas from Mayor Xavier Suarez and other officials, the situation escalated.[14] As their pelting by the crowd persisted, police fired tear gas at the crowd. Gunshots could be heard in the distance, according to witnesses.[15] Police immediately cordoned off Overtown and surrounding areas, and schools closed the following day.

As the evening progressed a news van was set ablaze, the police department ordered the media out of the area, and more police flooded in. Despite the police presence, looting soon began, and over the next couple of hours eleven people were arrested.[16] A second van, belonging to Associated Press reporter Mark Pesetsky, was also sent on fire. As Pesetsky and two colleagues attempted to take pictures of the unfolding unrest, a rock landed at their feet. He turned to his colleagues and said, “let’s go, get out of here.” By that time, however, a crowd had formed, and he was unable to retreat before being accosted.[17]

Mayor Suarez, who met with local Black leaders, hoped to calm the situation by conducting a press conference at 10 p.m. on the night of the shooting. In his televised message, he urged calm and patience from the black community, saying, “for the sake of our city, I appeal to every citizen to stay calm, get off the streets and stay home.” His pleas fell on mostly deaf ears in Overtown. The same could be said of his appeal to Black leaders. Suarez requested support from leaders for his administration’s attempt to quell the riots, in return promising a thorough internal investigation as well as an investigatory panel consisting of private citizens, appointed by the Miami City Commission, to investigate Lozano’s actions in the shooting.[18] Over two hundred were arrested, mainly youth, as young people refused to willingly ignore the use excessive force by the police, in addition to the other inequalities that had long plagued Black Miami. Miller Dawkins, the only Black member of the Miami City Commission, said he did not condone the violence, but also said, “I have a problem with a policeman who shoots a man for a traffic violation.”[19]

While most of the nation focused on the unrest in Overtown and its potential effect on the Super Bowl, there was another sporting event in town that was postponed due to the violence. The Miami Heat were in the middle of their inaugural season, playing at the Miami Arena located in the heart of the riots in Overtown. While the team had struggled that season, they had already captured the heart of the city. On January 17th, the Heat were scheduled to play the Phoenix Suns. Even though rioting had gripped the area since January 16th, many expected the game on the 17th to go on. In fact, no NBA game had ever been postponed due to civil unrest.

At 1 p.m., Miami City Manager Cesar Odio reassured the Heat organization that everything was safe. He made the same announcement at 4 p.m. Up until 7 p.m. the Heat ticket office was still fielding calls from fans about the status of the game, and they were responding that the game would proceed as planned. They did not cancel the game until 7:16, after many of the 15,000 fans were already on their way to the building. Fourteen minutes before tipoff, Heat Managing Partner Lew Schaffel grabbed the public-address microphone to apologize for the “inconvenience.” What to do about the thousands of fans who were on their way to the arena, navigating police barricades, burning buildings, and flying rocks and bottles, now became the focus. News reports suggested that the cancelation occurred an hour after the officiating crew’s car was struck by rocks, one of which smashed the windshield, on their way to the arena. The cancellation also occurred just forty-five to fifty minutes after a mob made its way down 8th Street, directly across the street from the arena, along its way bludgeoning cars and knocking out car windows.[20] Miami Heat center Rony Seikaly, who had been born in Lebanon and was often serenaded with racist taunts such as “go back to Lebanon, you terrorist” or “go home, you Arab,” said, “I grew up in war torn countries and the least I expected was me driving to an NBA game and having road blocks and we weren’t allowed to get to the game.”[21]

After three days of unrest, the city was still seething, but presumably the worst had passed. The Super Bowl was set to kickoff, and Miamians hoped their city could finally move on. Many Miami Heat fans hoped for normalcy, or as much as they could have. On January 19th, arguably the most famous athlete in the world was set to descend on Miami for his only appearance of the season. Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls were coming to town. The Heat organization wanted the game to go on, but they also were worried if the fans would show after the debacle two nights earlier.

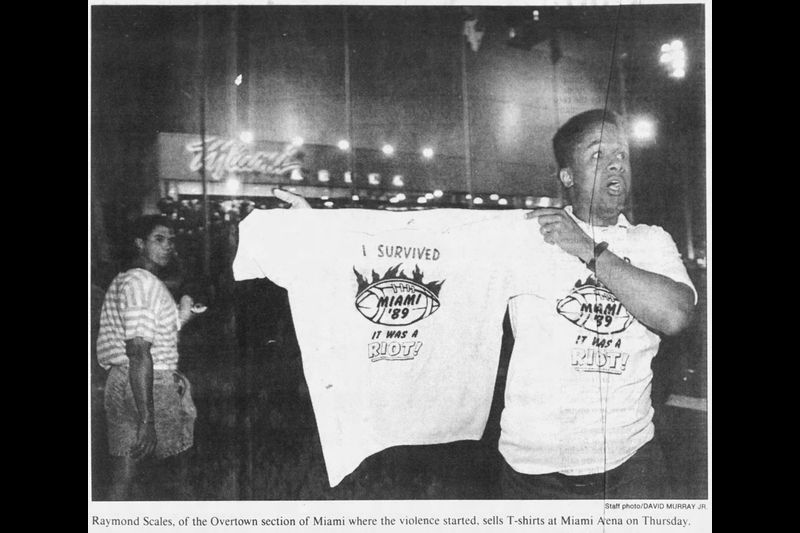

Once it was determined that the game would proceed, many looked at the contest as a dry run for the Super Bowl. Barry Jacobs, entering the Miami Arena with his 11-year-old son told a reporter, “Super Bowl weekend starts tonight, this is a big night.” Fifteen-year-old Vivian Guerra, when asked if there was any trepidation coming into Overtown as the riots were just now cooling down, said, “I came here tonight to see Michael Jordan. No, I’m not afraid. There’s no reason to be. It’s quiet tonight.” It was a quiet night, at least outside the arena, as over 100 heavily armed officers patrolled the streets to ensure the safety of the more than 15,000 spectators that showed up to see the Bulls barely hold off a determined Heat squad. Outside the arena a vendor sold shirts that seemed to mock the events that unfolded in the city over the past couple of days. The shirts read, “I Survived Miami ’89.” Under the words were flames shooting from a football with the words, “It Was a Riot!”[22]

According to Heat executive Pauline Winick, “Michael Jordan ended the Miami riots.” Andy Elisburg, the Heat’s vice president of basketball operations concurred, stating, “sports brought people back to the city and it ended what could have been a long problem,” with Heat radio announcer Eric Reid saying, “the great melting pot of a city was back together and the common cause was the Miami Heat; NBA basketball.”[23]

While this might have been hyperbolic, there was some truth to the statement. Sports did bring a sense of calm and normalcy to the city. Unfortunately, these statements remain extremely problematic as they exclude a large segment of the population. In this case they leave out arguably the most important segment of the populace, those directly affected by the riots–Black residents of Miami–who once again mourned one of their own, in this case two of their own, and who were again the victims of police brutality. Black Miamians, again, felt the system had failed them. Black Miami turned to rage, while white Miami looked to find hope through sports and entertainment. Miami is, and will be for the foreseeable future, a city trying to define itself and compose its legacy. But, while Miami’s history has been told, it is still being interpreted. Image is important to any city, but arguably nowhere is this more important than Miami, where tourism is the city’s leading industry, making it extremely important to city officials and others to constantly portray a positive appearance, even when faced with unrest such as the 1989 riots.

Seth A. Weitz grew up in Miami before heading to Louisiana for his undergraduate work at Tulane University. He received his MA and PhD from Florida State University in 2004 and 2007. Weitz is currently an associate professor of history at Dalton State College in Dalton, Georgia. His research interests include Southern U.S. History, Black America, and Florida History. He has authored, co-authored, edited, and co-edited numerous works, including A Forgotten Front: Florida During the Civil War Era, published by the University of Alabama Press in 2018. His next book, which looks at the social, political, racial and economic changes in Miami from the 1960s through the 1990s, entitled, City of Hope, City of Rage: Miami, 1968-1994 is forthcoming from the University of Alabama Press. He is also editing a collection of essays on the Civil Rights Movement in Florida, Confronting Jim Crow in Florida: The Long History of Civil Rights and Desegregation in Florida, to be published by the University Press of Florida.

Featured image (at top): Wall art on Calle Ocho (SW 8th Street), the vibrant artery of the historic Little Havana neighborhood of Miami, Florida, promoting the 2020 National Football League Super Bowl in Miami, Carol M. Highsmith, January 16, 2020, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

[1] https://www.Census.gov/quickfacts/ for Miami-Dade County, Florida; Broward County, Florida; and Palm Beach County, Florida.

[2] David W. Engstrom, Presidential Decision Making Adrift: The Carter Administration and the Mariel Boatlift, (New York: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, 1997), 36.

[3] Research Division, Metro-Dade Planning Department, 1990.

[4] Marvin Dunn, Black Miami in the Twentieth Century, (Gainesville: University of Florida Press), 305.

[5] “The Greatest Stories Never Told,” Sports Illustrated, February 2, 2004.

[6] New York Times, January 22, 1989.

[7] Dunn. Black Miami in the Twentieth Century, 306.

[8] The Harvard Crimson, January 18, 1989.

[9] Dunn, Black Miami in the Twentieth Century, 306.

[10] New York Times, May 29, 1993.

[11] New York Times, January 22, 1989.

[12] New York Times, January 22, 1989.

[13] The Harvard Crimson, January 18, 1989.

[14] Dunn, Black Miami in the Twentieth Century, 308.

[15] The Harvard Crimson, January 18, 1989.

[16] Dunn, Black Miami in the Twentieth Century, 308.

[17] The Harvard Crimson, January 18, 1989.

[18] New York Times, January 18, 1989.

[19] Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, January 20, 1989.

[20] Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, January 18, 1989.

[21] “Inside the Heat: 20th Anniversary Special,” Sun Sports, 2008.

[22] Fort Lauderdale Sun-Sentinel, January 20, 1989.

[23] “Inside the Heat: 20th Anniversary Special,” Sun Sports, 2008.