By Lisa A. Lindsay

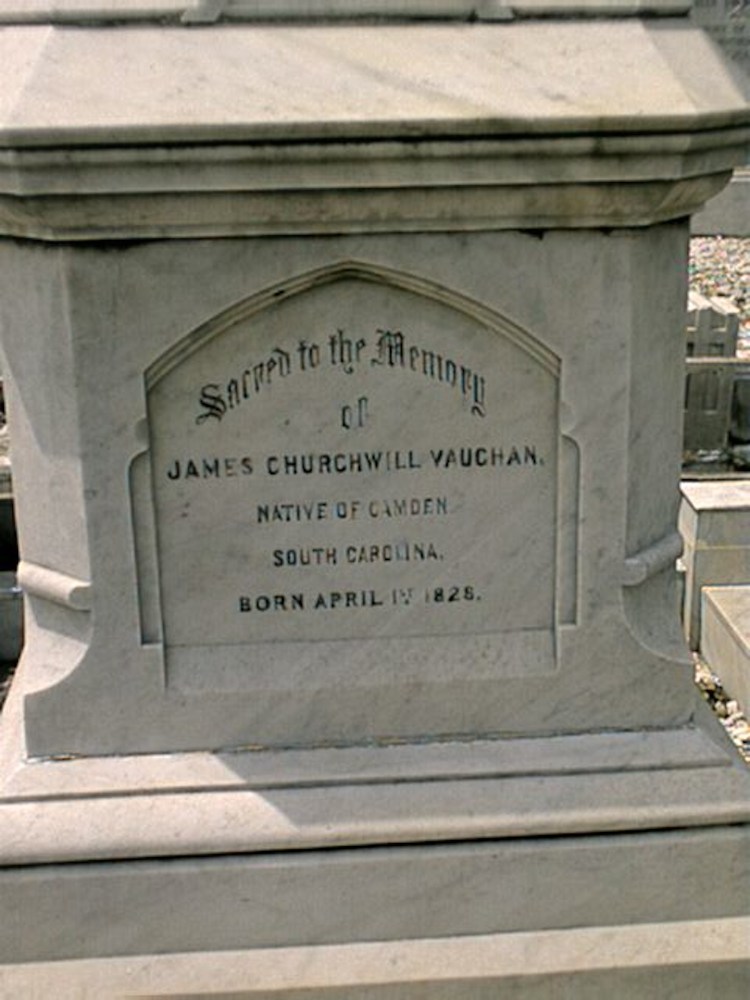

A decade before the American Civil War, James Churchwill (“Church”) Vaughan set out to fulfill his formerly enslaved father’s dying wish: that he should leave his home in South Carolina for a new life in Africa. With help from the American Colonization Society, he went first to Liberia, though he did not stay there long. In 1855, Vaughan accepted an offer of employment in Yorubaland—about which Americans knew virtually nothing–with Southern Baptist missionaries. Over the next four decades in today’s southwestern Nigeria, Vaughan became a war captive, served as a military sharpshooter, built and re-built a livelihood, led a revolt against white racism in missionary churches, and founded a family of activists. When his relatives were struggling in South Carolina in the late 1860s, he sent them canvas bags filled with gold. His descendants in Lagos and those of his siblings in the United States maintained contact for the next century. When Church Vaughan died in 1893, he left his widow and three children land, businesses, and multiple houses in central Lagos, and he was buried under an imposing monument in Ikoyi Cemetery.[1]

Vaughan’s remarkable story reveals two fundamental features of Lagos life, a century ago and now. First, this is a place where strangers came, and still come, to seek their fortunes. Originally a fishing village, Lagos had developed as an outpost for international slaving and then “legitimate trade” in palm oil and other tropical produce. By the late nineteenth century, the city was known as the “Liverpool of West Africa.” New settlers arrived, pulled by economic opportunities generated by the export trade and pushed by violence and insecurity in the interior that had begun with the disintegration of the Oyo Empire in the 1820s. In the 1860s, when Vaughan, his African wife, and their little son walked there after being expelled with other Christians from the inland town of Abeokuta, Lagos’s population was estimated at 25,000. He prospered as a carpenter and then as a merchant of building supplies, importing hardware and other materials for the houses and stores that newcomers continued to build. By 1881, the city had grown to 38,000, which included only 111 Europeans, despite the fact that Lagos had become a British colony twenty years earlier. The numbers kept increasing, so that by 1911 Lagos’s population numbered three times what it had been in 1866. People came for many reasons, including to escape interior warfare or slavery, or as part of another migrant’s retinue of dependents. But it was the lure of wealth through trade that called many of them to the city, even though few new migrants ultimately became rich. “The real Lagosian loves above everything else to be a trader,” a resident missionary wrote in 1881.[2]

Many of the most visible and prosperous traders were, like Church Vaughan, refugees from Atlantic world slavery. Ex-slaves from Brazil and Cuba, most of them Yoruba or of Yoruba descent, had resettled in Lagos (and nearby Whydah and elsewhere) since the late 1830s, largely through their own initiatives. They formed a residential and commercial quarter in the city, and many of them worked as carpenters, builders, or other artisans, giving Brazilian-style flourishes to the homes and businesses of their clients. Vaughan, in fact, lived among them and became their supplier when he went into the hardware business. The other significant group of newcomers were the so-called Saro, people who themselves or whose parents had been enslaved in the disintegration of the Oyo Empire, forced onto slave ships headed to Brazil or Cuba, been rescued at sea by British antislavery patrols and landed at Sierra Leone. They later made their way back to their areas of origin. By the mid-1860s, probably around 1,000 Sierra Leonians and equal numbers of Brazilians had settled in Lagos, and their numbers tripled over the next two decades. Their prior commercial experience, initial capital, contacts with Europeans, and western education enabled some Sierra Leonians to move quickly into the import-export trade and ascend to the top of the local elite. In fact, it was mostly Saro whom Martin Delany was describing when he noticed, passing through Lagos in 1859, that “The merchants and business men of Lagos [are] principally native black gentlemen, there being but ten white houses in the place…and all of the clerks are native blacks.”[3] Both they and the Brazilians literally made their mark on the city’s landscape. To this day, central Lagos’s streets bear the names of early returnees, including Savage, Cole, Doherty, and Davies in the Olowogbowo area settled by Sierra Leonians and Bamgbose, Pedro, Martins, and Tokunboh in the Brazilian quarter (Tokunboh meaning a person who has returned from abroad).

Church Vaughan’s remarkable life also serves as a reminder of the persistent ability of Lagosians to borrow creatively and make something new. In his case, it was his connections with the African diaspora that helped inspire him to lead a rebellion against racist white missionaries in the late 1880s. Taking inspiration from African Americans who formed their own churches and schools as a response to discrimination, in 1888 Vaughan and several others formed the first non-missionary Christian church in West Africa, the Native (later Ebenezer) Baptist Church in Lagos. But Yoruba people had long appreciated the potential of new ideas from elsewhere to improve things locally. The term ọ̀lajú, meaning “enlightenment” or “civilization” (from the Yoruba verb meaning “to open the eyes”) was first used in the mid-nineteenth century to describe the cultural package brought by European missionaries, including technical, medical, and clerical skills as well as Christianity. It also referred to those who were not necessarily well educated, but who gained worldly knowledge by pursuing opportunities away from home. Either way, the central idea was to use knowledge or experience from somewhere else to bring progress back home.[4] This was certainly what new arrivals in Lagos tried to do, building on trading connections or using ideas from places they had lived in order to pursue success in their new hometown.

This was built by Church Vaughan’s prosperous son, in the “Brazilian” style. (See https://www.lostinlagos.com/gist/159.)

The most famous Lagosian of the twentieth century may have been Fela Anikulapo Kuti, the pioneer musician and inveterate political critic, who died in 1997. Fela grew up in the town of Abeokuta, where his father had been a school principal and his mother led a massive women’s protest against a colonially-backed local ruler. After stints in London, Ghana, and Los Angeles, in the 1960s Fela made Lagos his lifelong home and creative muse. There, he created Afrobeat, an infectious musical style that blended local highlife, Yoruba melodies, jazz, and the funk of James Brown into something altogether new. Fela, like Church Vaughan and countless others, brought to Lagos the creative vitality of people on the move. The city has been built by people like them—refugees, entrepreneurs, and hustlers, who “opened their eyes” in multiple directions.

Lisa A. Lindsay is Bowman and Gordon Gray Distinguished Term Professor and Chair of the Department of History at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. A specialist in the history of Nigeria, the slave trade, and the Atlantic world, she is the author of Atlantic Bonds: A Nineteenth Century Odyssey from America to Africa, which won the African Studies Association’s prize for the best book in any field of African studies published in 2017. Previous publications include Working with Gender: Wage Labor and Social Change in Colonial Southwestern Nigeria (2003); Captives as Commodities: The Transatlantic Slave Trade (2008); and the co-edited volumes Men and Masculinities in Modern Africa (2003) and Biography and the Black Atlantic (2014).

Lisa A. Lindsay is Bowman and Gordon Gray Distinguished Term Professor and Chair of the Department of History at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. A specialist in the history of Nigeria, the slave trade, and the Atlantic world, she is the author of Atlantic Bonds: A Nineteenth Century Odyssey from America to Africa, which won the African Studies Association’s prize for the best book in any field of African studies published in 2017. Previous publications include Working with Gender: Wage Labor and Social Change in Colonial Southwestern Nigeria (2003); Captives as Commodities: The Transatlantic Slave Trade (2008); and the co-edited volumes Men and Masculinities in Modern Africa (2003) and Biography and the Black Atlantic (2014).

Featured image (at top): James Churchill Vaughn’s tombstone, Ikoyi Cemetery, Lagos, Nigeria.

[1] Lisa A. Lindsay, Atlantic Bonds: A Nineteenth Century Odyssey from America to Africa (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

[2] J. Buckley Wood, “On the Inhabitants of Lagos: Their Character, Pursuits, and Language,” Church Missionary Intelligencer (1881): 683-91, 687 quoted.

[3] M.R. Delany, “Official Report of the Niger Valley Exploring Party,” in Howard H. Bell (ed.), Search for a Place: Black Separatism and Africa, 1860, edited by (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), 113-14.

[4] J.D.Y. Peel, “Olaju: A Yoruba Concept of Development,” Journal of development Studies 14 (1978): 139-65.

Would like to get in touch with Dr Lisa Lindsay to see if she has ever thought of turning any of her books into a TV series.

Regards

Anthony Anozie MD

LikeLike

“Our actions or inactions of today, will be a prologue of future history”.

This masterpiece from Past history has confirmed my thoughts that we are all itinerant strangers in this wide world. We need to consider this world from all strangers’ perspectives to get a better view.

LikeLike

This is great and educating. Thanks for your effort in preserving the history of Nigeria. Dear Lindsay, have you heard about OldNaija? It’s an online platform based on Nigerian history and culture administered by me since 2014. You can check it out at https://oldnaija.com

LikeLike

Interesting

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing this. My dad shared a few of this account with me.

LikeLike