By Dennis Patrick Halpin

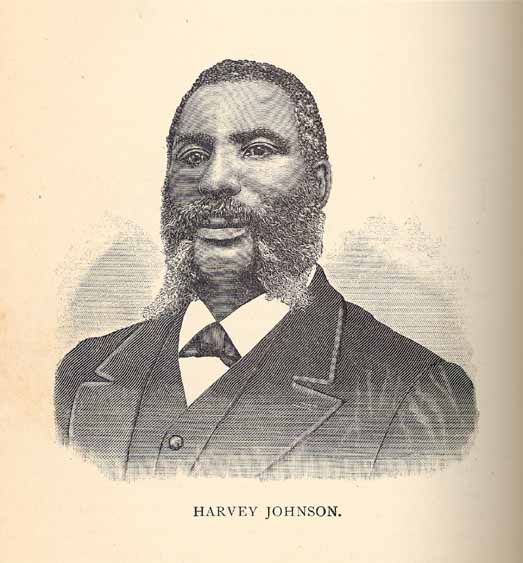

On June 2, 1885, Reverend Harvey Johnson called five of his fellow clergymen and close confidants —Ananias Brown, William Moncure Alexander, Patrick Henry Alexander, John Calvin Allen, and W. Charles Lawson—to his Baltimore home. During the previous year, Johnson had orchestrated challenges to public transportation segregation and Maryland’s prohibition on black attorneys. Now he hoped to accelerate the fight for racial equality by forming Baltimore’s first civil rights organization, the Mutual United Brotherhood of Liberty.

The founding of the Brotherhood of Liberty was a turning point in the long history of the black freedom struggle. The Brotherhood, active between 1885 and 1891, was not only Baltimore’s first civil rights organization but also one of the first in the nation. Its vision for racial equality, its strategies, and its uncompromising demand for civil rights laid the groundwork for later national groups including the Afro-American League and the Niagara Movement.[1] The organization also made Baltimore the epicenter for movements that challenged the emergence of Jim Crow in the late nineteenth century.

Johnson’s decision to form the Brotherhood did not occur in a vacuum. In fact, Baltimore’s history and circumstances made it particularly fertile grounds for civil rights activism by the time Johnson organized the Brotherhood. Baltimore had straddled the border between different worlds. It was a city with slaves located in a slave state. But Marylanders were divided on the issue of slavery, and the institution’s importance to Baltimore’s economy waned as the Civil War approached. By the 1830s, Baltimore was home to the largest free black population in the country. Free black Baltimoreans had organized schools and protested against slavery and colonization throughout the antebellum era. Finally, Baltimore was a port city that welcomed immigrants and their presence would make instituting Jim Crow complicated for segregationists in Maryland.[2]

Baltimore’s borderland status continued to play a role during the Reconstruction Era. Although it is tempting to see the Border States as the moderate middle between the Confederacy and the Union, this borderland status actually made states like Maryland more fraught for African Americans after the Civil War. Since Maryland had not seceded from the Union, it did not undergo federal Reconstruction like states further south. Furthermore, Maryland did not have a strong Republican Party, which had helped African Americans vote and win elected office throughout the former Confederacy. In 1868, the Democratic Party had regained control over the state government and rewrote the state constitution to negate the meager steps Maryland had taken towards racial equality.

With political avenues all but closed, black Marylanders (including many Baltimoreans) built upon the activism of the antebellum era by adjusting it to match the realities of the post-emancipation world. During Reconstruction, the federal government passed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which guaranteed “full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of person and property” regardless of race.[3] African Americans used this legislation to ignite a new era of political and social protest in Maryland through the courts. Throughout the 1860s and early 1870s, black Marylanders mounted several legal challenges to racial inequality. African Americans contested a law that barred them from testifying in court against white citizens. They petitioned the courts to end the odious practice of “involuntary apprenticeship” that allowed slaveowners to extend the life of slavery past the end of the Civil War. Between 1866 and 1871, a number of black Baltimorean men and women either purposefully violated segregation laws or filed lawsuits to challenge discrimination. Their efforts paid off: in 1871, the US Circuit court ordered streetcars open to black and white riders; black Baltimoreans had desegregated public transit in the city.

During this period, black Baltimoreans also looked beyond Maryland’s borders. Activists sought to make common cause with African Americans in other Border States and further south in order to pressure the federal government to intercede on their behalf. Black Baltimoreans planned and hosted a Colored Border States Convention in 1868. The next year they organized a National Convention of Colored Men to demand racial equality. Isaac Myers—an entrepreneur, activist, and labor organizer—started his efforts locally. After white waterfront workers forced black caulkers from the jobsite on the Baltimore waterfront in 1866 he helped build a co-operative shipyard to provide needed jobs. Myers then looked nationally when he helped organize the National Colored Labor Union in 1869.

This was the politically charged atmosphere that Harvey Johnson entered when he moved to Baltimore in 1872. Johnson was born into slavery in Fauquier County, Virginia in 1843. In 1868, the twenty-five year old Johnson found his calling in the Baptist church and moved to Washington, D.C. to enroll at Wayland Seminary. After graduating, Johnson accepted a pastorate at the small Union Baptist Church in Baltimore, which at the time only had 250 members. Johnson initially focused on expanding his church. By 1875, Johnson grew the church’s membership to 928 congregants. By 1885, Union Baptist had over 2,200 parishioners, which made it the largest and most influential black church in Baltimore.[4] Just as importantly, Johnson helped build new black Baptist churches across the city and state in the 1870s and 1880s. In total, at least fourteen churches and eleven ministers traced their roots to Union Baptist and/or Johnson’s mentorship.[5] These churches not only tended to the spiritual needs of black Baltimoreans but also provided spaces to organize. At each of these churches, Johnson’s allies became ministers and political allies.

As Johnson and his cohorts were building their churches, African-American activism in the city underwent important changes. In part, this was influenced by national developments. In early 1883 the Supreme Court upended parts of the Civil Rights Act of 1875. This meant that the federal government could no longer assure African Americans equal accommodations and equality on transportation, or guarantee that they could serve on juries. This decision came on the heels of others that had scaled back the protections instituted during Reconstruction.

These developments infuriated Johnson and other activists. Beginning in the early 1880s, many black Baltimoreans advocated abandoning both political parties. Johnson was one of these individuals. At a meeting in 1883, Johnson said “that the condition of the colored people of Maryland was worse than in any other State, that the laws relative to them were enacted before the war were still in force.” The minister listed numerous wrongs including the state’s prohibition on black attorneys, its bastardy law that punished African-American women, and its jury selection system that excluded black Marylanders. For Johnson, the moment to act had come. He ended his speech by predicting that “the day was dawning when the power of the colored people in Maryland would be seen and felt.”[6] What is particularly interesting about Johnson’s speech is that the wrongs he listed would all be things that he challenged individually or as part of the Brotherhood.

out-26About year after this speech, Johnson and his parishioners opened a new chapter in Baltimore’s fight for equality. The events of 1884 and 1885 were crucial in Johnson’s plan to build a civil rights organization in Baltimore. On August 15, 1884, six of Johnson’s parishioners boarded the Steamer Sue, which plied the waters between Maryland and Virginia. The travelers—including Martha Stewart, Winnie Stewart, Mary M. Johnson, and Lucy Jones—had reserved a first-class sleeping cabin for the night’s journey. When they attempted to retire for the evening, the steamboat’s agents refused them entrance and offered to house them in “first class” accommodations reserved for blacks in another part of the ship.

The women, who had previously taken this journey and knew that they were likely to face discrimination, had experience challenging their treatment. In 1882, Winnie Stewart recalled that two of her sisters had refused the steamboat operator’s demands to leave their first class accommodations. The women’s aunt, Pauline Braxton, had similarly refused these orders on another earlier voyage. Upon their return to Baltimore, Johnson helped them file a lawsuit against the Baltimore, Chesapeake and Richmond Steamboat Company that operated the Steamer Sue on the grounds that it violated the Fourteenth Amendment. The women prevailed, though the damages they recovered were considerably less than they had hoped for and the judge issued a narrow ruling that did not speak to the larger questions about whether segregation violated the Fourteenth Amendment.[7]

Despite the limited victory, Johnson was encouraged. In the wake of the Steamer Sue case, he spearheaded a new effort to get a black attorney admitted to the Baltimore bar. In 1885, Johnson contacted Charles S. Wilson. The thirty-year-old Wilson had graduated from Amherst College. After earning his license to practice law, he worked as an attorney in Boston before he moved to Maryland to teach in the town of Sunnybrook.[8] Wilson agreed to challenge Maryland’s prohibition of black attorneys before the city’s Supreme Bench on the grounds that the exclusion violated the Fourteenth Amendment. On March 19, 1885 the city’s Supreme Bench overturned Maryland’s 1872 exclusionary law, although their decision only applied in Baltimore.[9] For African Americans the decision was an important victory. Activists could now hire attorneys dedicated to fighting inequality.

The culmination of these two cases helped Johnson lay the foundation for the Brotherhood of Liberty. Local grievances and developments were important catalysts but Johnson was also influenced by national developments. The Brotherhood’s founding came at an important juncture in the long struggle for civil rights. During the early 1880s, African-American journalists across the nation, including Ida B. Wells, T. Thomas Fortune, and John Mitchell, Jr. used their newspapers to challenge the advent of Jim Crow. In New York, Fortune—whose newspapers were read in Baltimore—began promoting the idea of a permanent, non-partisan civil rights organization as early as 1884. Although it would take years for Fortune to realize his plan, the Brotherhood quickly incorporated many of his ideas to challenge racial inequality in Maryland. The group organized independently, demanded the fulfillment of the Constitution’s promises of civil rights, and aggressively challenged discrimination.

Over the course of the next six years the Brotherhood became a force in Baltimore and Maryland. After overturning Baltimore’s prohibition on black attorneys, Johnson convinced recent Howard graduates Everett J. Waring and Joseph S. Davis to move to Baltimore. With their legal team set, the group helped organize a successful challenge to Maryland’s prejudicial bastardy law. They undertook numerous protests against educational inequality, eventually compelling the city to fund a new African American high school and staff it with black teachers. The Brotherhood also defended black laborers who had rebelled over deplorable working conditions on Navassa Island, located off the coast of Haiti. That case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court where the Brotherhood’s Everett J. Waring became the first black attorney to present an argument before the highest court in the land.

As politicians, citizens, and the courts slowly rolled back the modest gains made during Reconstruction, the Brotherhood of Liberty challenged the dictates of the emerging Jim Crow Era. Even as the organization faded in the early 1890s it left behind important legacies. Johnson and Alexander continued to lead a variety of movements for racial justice in the city. Johnson would become one of the earliest members of the Niagara Movement, the forerunner to the NAACP, while Alexander organized efforts in the early 1900s to stop Jim Crow disfranchisement. On August 13, 1892, Alexander published the first issue of the Afro-American from Sharon Baptist. In the years to follow, the Afro-American became a potent counterweight to the city’s white papers, provided a platform for black businesses, churches, and individuals and, perhaps most importantly, served to highlight nationwide and local racial injustices, as well as the efforts of activists to fight them. Alexander would successfully lead the fight against Maryland’s efforts to disfranchise African Americans in the early 1900s.[10]

For many black Baltimoreans, the modest steps toward equality in the Reconstruction Era did not occur between 1865 and 1877 as they had for African Americans living further South. Instead, they began in 1884 when black Baltimoreans spearheaded judicial challenges to inequality and organized the Brotherhood of Liberty. The Brotherhood’s use of test case litigation also reverberated throughout the nation. In 1887, T. Thomas Fortune contemplated the direction of his Afro-American League, the first nationwide civil rights organization. Joseph S. Davis, one of the Brotherhood’s attorneys, wrote to Fortune’s New York Freeman to offer his support and weigh in on the deliberations. “The time has come when we have got to fight our greatest battles,” Davis declared, “and win our greatest victories in the courts and at the bar of public opinion.” Davis proposed pursuing test cases to achieve civil rights to “try the strength of our great Constitution.” “To accomplish this result we must follow such cases as are suitable from the station house to the Supreme Court. We must employ the best legal talent attainable,” Davis argued, “and we must pay these men and pay them well. Here the League can make itself heard, felt and respected.”[11] Davis spoke from experience. This was a vision that the Brotherhood of Liberty had already put into practice in Maryland. Now it would serve as the blueprint that other national civil groups would follow throughout much of the twentieth century.

Dennis Patrick Halpin is an Assistant Professor of History at Virginia Tech. His book, A Brotherhood of Liberty: Black Reconstruction and its Legacies in Baltimore, 1865-1920, is forthcoming from the University of Pennsylvania in spring 2019.

[1] For more information on the early stages of the black freedom struggle in the United States, see: Susan D. Carle, Defining the Struggle: National Organizing for Racial Justice, 1880-1915 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013) and Shawn Leigh Alexander, An Army of Lions: The Civil Rights Struggle Before the NAACP (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2012).

[2] Black Baltimoreans developed a history of activism stretching back to the antebellum era. For Baltimore’s antebellum era, see Christopher Philips, Freedom’s Port: The African American Community of Baltimore, 1790-1860 (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1997), Seth Rockman, Scraping By: Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009) and Martha S. Jones, Birthright Citizens: A History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

[3] “The Civil Rights Bill and its Consequences,” The Baltimore Sun 9 April 1866, p. 2.

[4] George F. Adams, Baptist Churches of Maryland (Baltimore: J.F. Weishampel, Jr. 1885) p. 130-32 and A.W. Pegues, Our Baptist Ministers and Schools (Willey & Co: Springfield, MA 1892) 89, 291.

[5] “Funeral of Reverend Wm. M. Alexander on Monday,” The Afro-American Ledger 11 April 1919, p. A1 and “Sharon Baptist Church,” The Afro-American Ledger 17 February 1912, p. 7. A. Briscoe Koger, “Dr. Harvey Johnson—Pioneer Civic Leader,” (Baltimore: Self-Published, 1957) 3.

[6] “Movement of Colored People,” The Baltimore Sun 25 April 1882, p. 1.

[7] Accounts of the “Steamer Sue” case taken from: “District Court, D. Maryland. The Sue,” Westlaw 2 Feb. 1885 22F.843; Koger, “Dr. Harvey Johnson: Minister and Pioneer Civic Leader, 9-10; “Colored Passengers,” The Baltimore Sun 3 February 1885, p. 6.

[8] “Can Colored Men Be Lawyers,” The Baltimore Sun 16 February 1885, p. 6 and F. Johnson, “Legal Lights of Baltimore,” The Afro-American Ledger 26 March 1910, p. 6.

[9] “Admitted to the Bar,” The Baltimore Sun 20 March 1885, p. 1 and “Admission of Colored Lawyers to the Bar,” The Baltimore Sun 20 March 1885, p. 2.

[10] For information on the publishing history of the Afro-American see: Hayward Farrar, The Baltimore Afro-American, 1892-1950 (Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1998).

[11] Joseph S. Davis, “A Baltimore Lawyer’s View of the Case,” The New York Freeman 16 July 1887, p. 1. I found this letter through: Carle, Defining the Struggle, p. 56.

One thought on “The Brotherhood of Liberty and Baltimore’s Place in the Black Freedom Struggle”