Security clearances have been a topic of great controversy in recent months. The process of issuing access to government secrets has always been opaque, but for decades it was also discriminatory. In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower issued executive order #10450, which banned homosexuals from government employment and labeled them a threat to national security. “Throughout the 1950s and 1960s the term ‘security risk’ in fact functioned largely as a euphemism for homosexual,” notes historian David K. Johnson. For gay and lesbian Americans, gaining a clearance proved nearly impossible.

Thousands of employees lost their jobs due to their sexual orientation. Tens of thousands more abandoned any hopes of working for the federal government in policy positions and elsewhere, to say nothing of how private business followed suit.

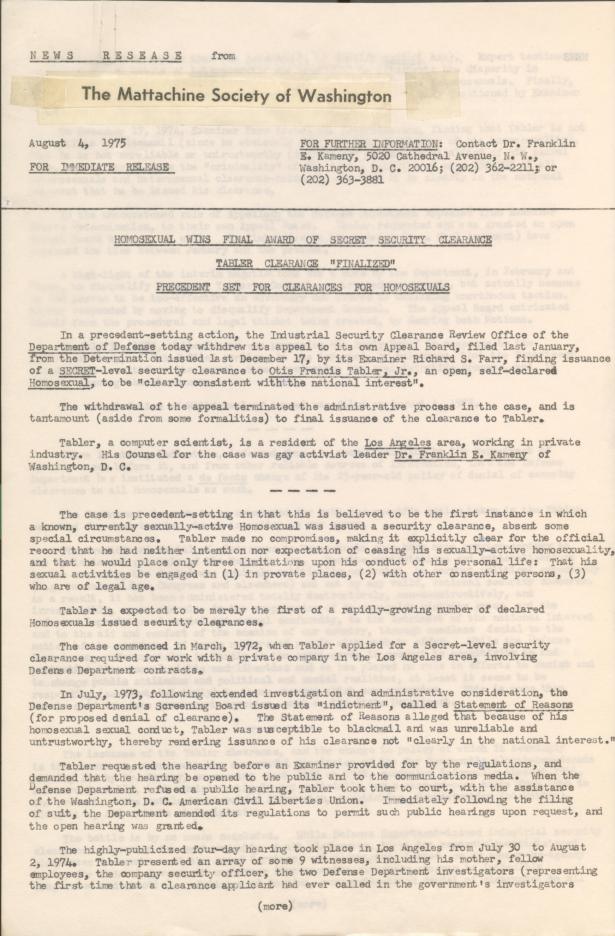

Circumstances began to change in 1975 when Otis Francis Tabler, a suburban Los Angeles resident and computer defense systems analyst, with the help of Washington, D.C. LGBT activist Frank Kameny, became the first openly gay individual to gain a security clearance from the United States government.

World War and the Post War Defense Industry

World War II and the postwar rise of the military industrial complex radically reshaped Southern California. Los Angeles and Orange County attracted new installations and defense industries, particularly in aerospace. By the early 1960s, 43 percent of manufacturing employment in the two counties was tied to government aerospace contracts. This process persisted into the 1970s by which time L.A and the “surrounding region had come to rely to an extraordinary degree upon the related industries of defense aircraft space and electronics,” notes historian Roger Lotchin.

Demographically, California and the West changed as the population boomed and diversity increased. San Francisco, Los Angeles, and San Diego served as critical nodes in the mobilization for war. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers and others moved to the Golden State. The gender segregation of the military, as demonstrated by historian Allan Berube, provided the opportunity for same sex relationships while the unsupervised nature of urban living provided the means. “Because L.A. has a port and vast numbers of soldiers landed there, far from watchful eyes ‘back home’ and yearning for rest and recreation they enjoyed unprecedented opportunities for gay experiences,” add historians Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons. Military officials attempted to squash such developments. “The war mobilization laid the groundwork for a national effort to eliminate homosexuals from public life,” historian Daniel Hurewitz points out.

In the face of such hostility, Harry Hay and others formed the Mattachine Society in 1951. Through the organization Hay constructed what would become the homophile movement and the Los Angeles Mattachine emerged as its first real organization. It enabled gay men and women to form a community and present a collective identity to a hostile, questioning public.

Despite military policies and discriminatory public attitudes, gay men and women built lives for themselves in and around Los Angeles; when the war ended and the defense industry expanded in Southern California many sought new work opportunities. One such individual was Otis Francis Tabler, a computer scientist who studied missile defense systems at Logicon in San Pedro, California. According to his coworkers and supervisors, Tabler demonstrated considerable skill in carrying out his responsibilities, but due to his inability to secure the necessary security clearance, his talents were not being adequately utilized. His former supervisor Captain (USAF) Larry Wayne Kern believed Tabler to be honest, trustworthy, and reliable; Tabler had “a specific and unique contribution to make in the field,” he testified.16

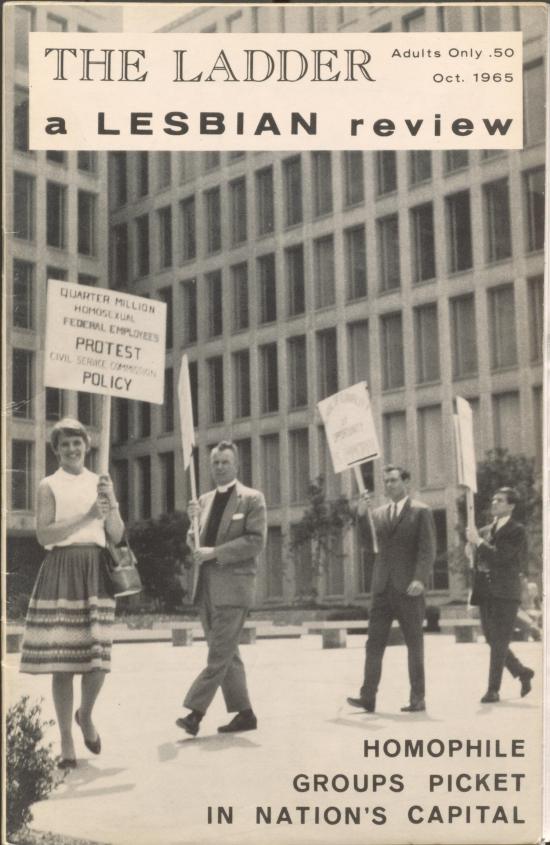

Few understood the effects of the policy better than WWII veteran Frank Kameny, who in 1957 was fired from his job in the Army Map Service for homosexuality. By 1961, Kameny had established the Mattachine Society of Washington (MSW). From his leadership position in the MSW during the 1960s, Kameny criticized the government’s “war on gays and lesbians” at every opportunity, even picketing the White House, Pentagon, and Civil Service Commission Headquarters. Kameny and his fellow MSW members demanded that the government “cease noting that they are homosexuals and ignoring that they are also American citizens.”

No stranger to activism, Tabler, inspired by the Civil Rights, Black Power, Chicano, and Feminist movements then roiling the nation, took part in what is now known as the Gay Liberation Movement, the more militant successor to the post-WWII homophile movement. Due to generational and ideological differences, some homophile leaders and activists had trouble aligning with the newer movement’s more aggressive tactics. Kameny bridged these differences. Having distinguished himself through his work during the 1960s, Kameny drew plaudits from Los Angeles’s Gay Liberation Front (LAGLF). As a result of these connections, Tabler reached out to Kameny who then represented the computer scientist at the first-ever open hearing regarding a security clearance in 1974.

The hearing, held over four days in late July and early August of 1974 at the Federal Building on Wilshire Boulevard, revealed a clearance process beset with contradictions that reflected broader societal biases of the day.Throughout the hearing, the federal government focused on Tabler’s violation of California sodomy and perversion laws as reasons to deny him clearance. Two heterosexual witnesses for Tabler, both of which held security clearances, admitted to engaging in similar activities but had never been questioned about them. Even a government investigator testified that officials only inquired about an individual’s sexual history when they were a suspected or an admitted homosexual. “In my opinion, the sodomy laws are merely words written on statue books,” Tabler told officials. “I believe that they do not exist.” 23

Nor could the government say Tabler represented a blackmail risk. He was an open homosexual. His mother knew of his sexuality, as did all his coworkers. Kamney and Tabler submitted dozens of affidavits from neighbors and acquaintances testifying to his homosexuality.

Though not a lawyer, Kameny represented Tabler and employed an unorthodox approach. His opening statement lasted over ninety minutes. He called the security clearance program bigoted, politically corrupt, and vile. He accused the DOD and federal government of conducting a war on gays waged “relentlessly, remorselessly and mercilessly.” The homosexual community did not want to fight, but “if [the government] want[s] a war they will get it,” he told the government examiner.

Tabler’s mother also testified, making an impassioned plea to the government that her son was a loyal American and that, as the widow of a disabled U.S. Air Force veteran, she loved her country. “But I’m horrified to find out that the Defense Department does not honor the Constitution of the United States,” she said, then breaking down in tears.

On December 17, 1974, government Examiner Richard S. Farr, who had supervised the hearing, ruled in Tabler’s favor, judging him worthy of a security clearance. The Department of Defense, however, appealed the decision and even attempted to disqualify Kameny as his counsel. Within a year, though, the DOD reversed course and dropped its appeal, notifying both Kameny and Tabler that it had changed its policies regarding homosexuals.

Tabler became the first openly homosexual person to gain a security clearance, though as Kameny noted in a Mattachine newsletter much work was left to be done, since now it needed to be determined that such policies would be followed; other branches of the government like the F.B.I. and C.I.A. conducted their own investigations and continued to discriminate against homosexuals.

Today, homosexuality is no longer an impediment to securing a clearance, opening up thousands of jobs to gay men and women. Undoubtedly, Otis Francis Tabler’s fight contributed to such developments.

The above post is based on some very fortunate archival discoveries in the Frank Kameny papers (and to a lesser extent the Lilli VincenzLilli Vincenz papers) located in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. Right now, I’m working on a longer article with greater analysis and stronger argumentation, however, crafting a short twelve hundred word summary of it has helped crystalize my thoughts on the subject. As I revise my longer article for publication, I now feel better prepared to explain the story and its significance to both fellow historians and the general public. In short, writing in public venues like The Metropole not only helps craft better public history but also sharpens one’s own writing clarity and precision. This is why we are holding our second annual Grad Student Blogging Contest. First prize claims $100 but as important is the value of contributing to a lively public discourse and active dialogue within the profession of urban history. It doesn’t hurt that a panel of distinguished, award-winning urban historians will judge it: UHA President Richard Harris, Pulitzer-prize winner and UHA President-elect Heather Ann Thompson, and standard-bearer in the field, Tom Sugrue, author of the foundational Origins of the Urban Crisis.

The rules are below, and there’s less than one month left until the July 15 deadline. We hope to read your submissions soon!

Striking Gold: The Metropole Grad Student Blog Contest

The Metropole/Urban History Association Graduate Student Blogging Contest exists to encourage and train graduate students to blog about history—as a way to teach beyond the classroom, market their scholarship, and promote the enduring value of the humanities.

The summer’s blogging contest theme is “Striking Gold.” With golden rays of summer sunshine in our near future, we invite graduate students to submit essays on lucre and archival treasures. Tell us how you found the linchpin of your dissertation argument hidden in a mislabeled folder, or share the history of an event or era characterized by newly-realized wealth.

All submissions that meet the guidelines outlined below will be accepted. The Metropole’s editors will work with contest contributors to refine their submissions and prepare them for publication.

In addition to getting great practice writing for the web and experience working with editors, the winner will receive a certificate and a $100 prize!

The contest will open on June 1 and will close on July 15. Entries must be submitted to uhacommunicationsteam@gmail.com. Posts will run on the blog in July and August, and we will announce the winners in September. Finalists will have their papers reviewed by three award-winning historians: Heather Ann Thompson, Tom Sugrue and Richard Harris. The winning blog post will receive $100.

Contest Guidelines

- Contest entrants must be enrolled in a graduate program.

- Contest entrants must be members of the UHA. A one-year membership for graduate students costs only $25 and includes free online access to the Journal of Urban History.

- Contest submissions must be original posts not published elsewhere on the web.

- Contest submissions must be in the form of an essay related to the theme of “Striking Gold.” Essays can be about current research, historiography (but not book reviews), or methodology. Essays that stick to the following criteria will be most successful:

- Written for a non-academic audience and assume no prior knowledge.

- Focused on one argument, intervention, or event, and not trying to do too much.

- Spend more time showing than telling.

- Posts must be received by the editors (uhacommunicationsteam@gmail.com) by July 1 at 11:59 PM EST to be eligible for the contest.

- Posts should be at least 700 words, but not exceed 2000 words.

- Links or footnotes must be used to properly attribute others’ scholarship and reporting. The Metropole follows the Chicago Manual of Style for citation formatting.