By Yovanna Pineda

On a casual stroll through Buenos Aires City, the pedestrian’s eyes can follow the public spaces lined with colorful graffiti. Though the latter is illegal, it is socially accepted, and for some urban residents and tourists it is even valued. Indeed, they locate their graffiti, including name tags, screen printing, and murals, in highly visible and trafficked areas to share messages or evoke memories across time and space.

Europeans learned the history of graffiti in Spanish America thanks to Hernán Cortés—even though he, in the words of Angel Rama, “condemned graffiti because anyone could produce it.” Yet that very condemnation of its popularity is—perhaps ironically—why it is such an effective art form throughout modern Latin America.[1] In Buenos Aires in particular, graffiti has become an art of protest, messaging, and spectacle.

The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo serve as evidence regarding graffiti art’s importance and its intersection with protest and public space. The Plaza de Mayo has symbolized Argentina’s urban core space since the early twentieth century. Through a discussion of the Mothers and how others use the Plaza space, we can better understand the strength of their physical protest and their ability to evoke memory

The Plaza de mayo

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, elite leaders sought to control spaces within the city. Influenced by positivist philosophy, they engineered public space to represent their bourgeois ideals of order and progress—and materialized their imagined modernization. [2] With rising city income from sales of exported cereals and beef, they were able to finance their new city, an “ordered city,” which they envisioned as an architectural urban style and grid that emphasized order and progress.[3] Such a new, ordered city would promote politics, public health, and culture.[4]

The core of this ordered city was a public square, the Plaza de 25 de Mayo, established in 1884.[5] Ironically, though termed a modern square, the Plaza de Mayo appeared similar to a traditional sixteenth-century Spanish plaza, surrounded by the essential buildings of administration, finance, and religion, including the presidential palace, the Casa Rosada Nevertheless, elites perceived that this central area demonstrated their high culture, including beautiful landscapes in geometrical shapes. This architectural landscape of Plaza de Mayo has remained relatively consistent for more than a century

By the mid-twentieth century, the Plaza de Mayo became less a symbol of beauty and modernization, and more of a central, public space for rallies and protests. During the Presidency of Juan Domingo Perón (1946-1955), for instance, his allies often organized pro-government rallies in the Plaza de Mayo, conveniently across from the Casa Rosada, where Perón could wave from the balcony of his office. The political and cultural significance of the Plaza was clear with numerous demonstrations taking place in this space—though the larger, truly mass demonstrations took place near the former building of the national labor organization, Confederation of General Labor (CGT), about a mile south of the Plaza.[6] International audiences likely became aware of the importance of this Plaza through English composer Andrew Lloyd Webber’s musical Evita. [7] In Webber’s version, he placed Evita on the balcony of the Casa Rosada during her iconic speech in which she announced her resignation as the vice-presidential candidate. In reality, her speech took place in front of the CGT building.

Evita’s Resignation Speech (Spanish Subtitles)

Protest and memory of the mothers of the plaza de mayo

During the second half of the twentieth century, mothers whose children had “disappeared” (desaparecidos) used the Plaza as a space of protest against the military dictatorship and its Dirty War (1976-1982). During this period, the military tortured, killed, and disappeared persons that it viewed as subversive. By 1977, fourteen women collectively demanded information regarding their missing children.[8] They eventually called themselves the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo. They silently walked around the Plaza every Thursday afternoon—and still do to this day. They wear white head kerchiefs, carry signs of their missing children to recognize each other, and allow onlookers to join them. They intentionally remained visible to be “politically effective” and stay alive during the Dirty War.[9] By the end of the Dirty War in 1982, they held large demonstrations in the Plaza demanding information on their disappeared children.

Though the founders of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo group have split into two, both groups, the Association of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo and the Línea Fundadora, continue to walk around the Plaza every Thursday afternoon. Both groups wear the head kerchief, which was once embroidered with the name and date of their disappeared loved one. Today, the kerchiefs are embroidered with “aparición con vida de los desaparecidos” (making visible the lives of the disappeared). Though most mothers have accepted the death of their loved ones, their weekly march continues to memorialize the living, and most importantly, remind Argentines how their lives were taken during the Dirty War.[10]

The two groups are distinguishable from each other only through their marching banners and followers. The first group, Línea Fundadora (founding mothers), is the smaller of the two and focuses on the original goal of the Mothers, demanding answers as to what happened to the disappeared. The second group, the Association of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, has a much larger following because they march for the disappeared and in support of other social justice issues.

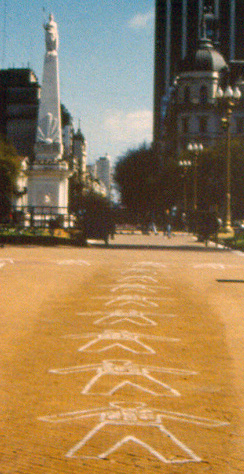

In addition to walking around the Plaza to protest, the mothers evoke memory even when they are not physically present. Through graffiti, they continue to demonstrate their power. In 1999, for instance, they drew outlines of the bodies of the disappeared on the Plaza de Mayo with white paint . Within each body they wrote the name of the disappeared and the date that they went missing. Through the display, the mothers made the disappeared “re-appear” on the Plaza. But the sketches of the bodies slowly faded with time. By 2002, they remained but were clearly fading as expected, having a ghostly appearance, such as an apparition

During the early twentieth century, the mothers varied the symbolic graffiti art painted on the Plaza. The head kerchiefs had become a symbol of the Mothers; hence, their allies painted them in white paint on the Plaza de Mayo in 2002. That same year, there were numerous protests on the Plaza in response to the major economic crisis of December 2001. The piqueteros (protesters) set up signs, posters and audio speakers to demonstrate in the Plaza. They were physically located near the painted head kerchiefs on the Plaza. The synergies of the protests highlighted the importance of creating spectacle to enhance the power of dissent.[11]

By 2016, the Mothers and their allies combined the white outline of the disappeared bodies and the kerchiefs on the Plaza. This time, the bodies were painted in dynamic poses, resembling ghostly figures moving along the plaza, rather than the original drawings of static figures in 2002

Today, the Plaza continues to be a diverse urban core space for protests. In addition to the Mothers, veterans and a host of groups representing social, environmental, and economic justice issues use graffiti or install art in the Plaza. In 2016, a reproductive justice group demanded legal abortions in hospitals to reduce the number of injuries or deaths due to illegal procedures. Painted clearly on the divider fence is “aborto legal en el hospital,” which ironically, is behind the painted kerchiefs of the Mothers (Image 14. Aborto Legal). It is a message for women’s rights to control their own bodies, and that women should have the right to choose whether they want to be mothers or not.

Representations of the mothers across the city

Graffiti in the city includes themes of encouragement, love, identity, soccer, labor, and of course, protest. It is so varied that a few tourist companies specialize solely in graffiti tours in the northern and southern parts of the city. They offer bike, walking and shuttle tours, helping commodify graffiti. The influence of the mothers has been strong in this process across space and time. On graffiti tours, the guide cannot skip the homage to the Mothers. In the upscale Palermo district/neighborhood, the mothers’ white head kerchiefs are painted on the side of a building facing a playground. The kerchiefs float above all the other graffiti on this wall, and appear like powerful ghosts

In the south side of the city, artists in the working-class neighborhood of Boca represent the mothers as powerful indigenous warriors, showing their physical and emotional strength that helped carry the movement of memory and protest.

In the final image, the names of the missing in Boca are listed on the wall, and clearly written is “Ni Olvido, Ni Perdón.” It powerfully conveys the message that the struggle will continue until each and every disappeared person is accounted for.

Dr. Yovanna Pineda is Associate Professor of history at the University of Central Florida. Currently, she is finishing her manuscriptInnovating Technologies: Farm Machinery Invention, Rituals, and Memory in Argentina and its companion documentary The Harvester. She has published works on various topics including industrialization, farm machinery users, development, patent records, and labor. She writes articles about advising and empowering our first generation students. Her courses on the history of South America, science, and the global drug trade focus on how culture, politics and economics intertwine.

Dr. Yovanna Pineda is Associate Professor of history at the University of Central Florida. Currently, she is finishing her manuscriptInnovating Technologies: Farm Machinery Invention, Rituals, and Memory in Argentina and its companion documentary The Harvester. She has published works on various topics including industrialization, farm machinery users, development, patent records, and labor. She writes articles about advising and empowering our first generation students. Her courses on the history of South America, science, and the global drug trade focus on how culture, politics and economics intertwine.

[1] Angel Rama, The Lettered City (Duke University Press, 1996), p. 38. [Italics added].

[2] Auguste Comte, Cours de Philosophie Positive (Paris: Bachelier, Imprimeur-Libraire, 1839); The porteño (as Buenos Aires was known) elite were very much aware of the international Park Movement, and interested in shaping spaces like Georges-Eugène Haussmann had done for Paris. Adrián Gorelik, La grilla y el parque: Espacio público y cultura urbana en Buenos Aires, 1887-1936 (Bernal: Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Editorial, 2010).

[3] Gorelik, Chapter 1, “Ciudad nueva: La Utopía del ‘Pensamiento Argentino’,” La grilla y el parque.

[4] Angel Rama, The Lettered City; Gorelik, La grilla y el parque.

[5] May 25, 1810 is the declaration of independence day. Today, this space is simply known as the Plaza de Mayo.

[6] Regarding the struggle for physical and symbolic space, see Mariano Ben Plotkin, Mañana es San Perón: A Cultural History of Perón’s Argentina, translated by Keith Zahniser (Wilmington, Delaware: SR Books, 2003)

[7] Andrew Lloyd Webber wrote the lyrics to “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina” depicting Evita Duarte de Perón’s resignation speech of the vice-presidency in his musical Evita (1978).

[8] An estimated 30,000 persons were disappeared during the Dirty War (1976-1982).

[9] Diana Taylor, “Making a Spectacle: The Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo,” Journal of the Association for Research on Mothering, Volume 3, number 2 (2001): 97-109.

[10] Vikki Bell and Mario Di Paolantonio, “The Haunted Nomos: Activist-Artists and the (Im)possible Politics of Memory in Transitional Argentina,” Cultural Politics, Volume 5, number 2 (2009): 149-178.

[11] Diana Taylor and Juan Villegas, editors, Negotiating Performance: Gender, Sexuality, and Theatricality in Latin/o America (Duke University Press, 1994).