Our second entry in The Metropole/Urban History Association Graduate Student Blogging Contest explores the role of the New York Times in NYC school integration debates during the early 1960s through the lens the newspaper itself and the Pulitzer Prize winning work of Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff’s work, Race Beat: The Press, The Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation.

During the 20th Century, a strategic decision was made by media outlets to associate America’s race problem with the South. To uphold this one-sided narrative, actions, and events regarding Martin Luther King Jr., the Montgomery Bus Boycott and school integration in Alabama were strategically covered by journalists. This has been recognized in Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff’s Race Beat: The Press, The Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation. In meticulous detail, Race Beat explains the role of the press as it traced events of racial confrontation across the South, the book emphasizes information crucial to the development of black and white media sources.

Undeniably, the media played a central role in the civil rights movement; as former Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) leader and Congressman John Lewis observed, “If it hadn’t been for the media … the civil rights movement would have been like a bird without wings, a choir without a song.”[1] This framing presented the relationship between the media and movement as inseparable. But when we flip the question, what do we see when exploring the New York Times’s relationship to civil rights activism in the North? The bird didn’t have wings in cities like New York, given the media’s tendency to dismiss and disparage the movements there.

In January of 1964, a decade-long movement demanding desegregation of New York City’s public-school system came to a peak. Ten years after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, civil rights activists in New York City (like their Southern counterparts) had grown weary of the gradual progress in the movement for racial equality. Building on the momentum of 1963’s widespread grassroots organizing, New York activists looked to resume civil disobedience through a series of protests that targeted the Board of Education (BOE) for their failure to create and implement a reasonable integration plan. After much debate and a decade of official intransigence, numerous New York activists, both African American, and white, decided that a one-day mass school boycott would be a productive step forward.

On February 3rd, 1964, 464,361 students and teachers of color participated in the school boycott to dramatize the poor conditions in predominately African American and Puerto Rican schools.[2] This protest has been recorded as the largest civil rights protest in American history, surpassing even the 1963 March on Washington. This demonstration could have been a decisive opportunity for the media to oppose and expose segregation in the city and all of those who maintained it. Unfortunately, what we see from the Times is complacency and even opposition; while grudgingly noting the massiveness of the protest, they diminished the existence and negative impact of segregation in city schools, only to characterize the boycott as “unreasonable” and activists as “reckless” and “violent,” ultimately furthering support for the white power structure within NYC.[3]

The February 3rd, 1964 “Freedom Day” protest was directed by Bedford-Stuyvesant’s Reverend Milton A. Galamison of Siloam Presbyterian Church.[4] Reverend Galamison had moved from Philadelphia after attending Lincoln University and lived with his wife and son in Brooklyn. Galamison had made previous attempts to negotiate with city officials, but even under the guidance of Mayor Robert F. Wagner, who was known as New York City’s most “Liberal Mayor,” city officials had been lackadaisical in their approach to school integration.[5] The reverend had hired civil rights activist Bayard Rustin to help organize the boycott. Rustin had recently helped organize the 1963 March on Washington, which drew a crowd of 200,000 people, and was working as the Executive Secretary for the War Resisters League.[6] In a profile, the Times depicted Rustin as a lifelong activist with a talent for “putting demonstrators in demonstrations and pickets in picket lines.”[7] While the Times was eager to profile Rustin for the boycott, possibly because of his international presence, they ignored Galamison, the boycott’s director, in addition to the parents and teachers who dedicated their expertise to the cause. Grassroots activists from Brooklyn’s Congress of Racial Equality, The Parents’ Workshop, National Advancement Association of Colored People (NAACP) and Harlem Parents Committee showed support for the boycott in February of 1964, but these activists also went unnoticed by the paper.[8] Given Galamison’s strong presence in the community, it would have been easy to produce a comprehensive profile that showed his dynamic character. As momentum for civil rights in NYC persisted, opposition to the protest from white liberals continued, many complaining that leadership within the African American community had “taken a turn for the worst”.[9]

In the coverage leading up the school boycott the Times failed to see the demonstration as part of the larger movement. An editorial titled “No More School Boycotts” framed the demonstration as “tragically misguided” and generalized all boycotts as “pointless”, “dangerous” and “destructive” to the children of New York.[10] The newspaper castigated Reverend Galamison and let it be known that, when concerning segregation in New York City, “there is no realistic way to alter the balance.” However, the Times suggested that it’s up to the “reasonable” civil rights leaders to mend ties with their liberal counterparts.[11] In 1964, activists were calling on the BOE to create an integration plan that is “complete and city wide” instead of the “piecemeal” Princeton (paring) Plan,[12] which asked for small portions of the city to be bused, leaving the majority of predominately African American and Puerto Rican schools segregated. What this Times article ignored was the fact that cities like New York had been segregated though racist housing policy, government zoning and neighborhood pacts by whites to keep communities racially homogenous.

Following the boycott, the February 4th, 1964 issue of the Times stressed a variety of opinions, analyzing the role of educators and students, while also shedding light on what reporters considered the flaws and successes of the boycott. Times correspondent Homer Bigart reported that the boycott “was even bigger than last summer’s March on Washington” which had been the biggest civil rights demonstration to date.[13] In an article titled “Leaders of Protest Foresee a New Era of Militancy” long-time journalist, Fred Powledge wrote of the boycott as a communal effort in which “people of all kinds” joined the effort to make food, posters, and prepare lessons for the one-day boycott directed by Bayard Rustin.[14] Powledge failed to recognize that the demonstration was a significant step within a much larger movement that was orchestrated by New York City activists, with the help of Rustin. This inaccuracy minimizes the efforts conducted by activists in New York and emphasizes the Times’s failure to recognize grassroots activists who made the boycott successful.

Meanwhile, reporter McCandlish Philips felt that Freedom Day was “not very useful” and quoted Dr. John H. Fisher, President of Columbia University’s Teachers College at the time, saying the “boycott was a mistake from the beginning.”[15] Many liberals aligned with this sentiment, declaring that things were moving too fast, including Rabbi Max Scheck, President of the New York Board of Rabbis who was quoted saying, “They’ve been waiting for 100 years now…we’re asking them to wait a little longer.”[16] The notion that African Americans needed to be patient and wait for societal standards to change gradually was a philosophy often articulated by segregationists in South.

Not all reporters failed to see this demonstration as a singular act. Seasoned reporter Peter Kihss placed the boycott within the larger movement in his article “Many Steps Taken for Integration.” Kihss emphasized the boycott as one of many demonstrations by Northern civil rights activists, who had been working to create equal opportunities for the children of NYC since the 1950s.[17] Kihss focused on the longtime struggles made by civil rights activists such as African American lawyer Paul B. Zuber and Galamison, applauding their ability to continue the battle even as “white parents remain hostile” to desegregation efforts in New York.[18] With the exception of Kihss, Times journalists failed to mention that white backlash was embodied in the Parents and Taxpayers Organization, whose organizing was rooted in a racist ideology.

Reports published by the Times on the boycott showed there was a consistent impact on school attendance, stressing that 44.8 percent of the total enrollment had not shown up, but recording that the average absentee rate hovered around 10 percent.[19] Numbers showed that in predominantly white communities attendance was hardly affected. Staten Island for example had a slight increase in attendance, with an absentee rate of 11.2 percent.[20] Reporter Robert Trumbull explained that the Citywide Committee for Integration of Schools noted that more than “400 Freedom Schools had functioned for pupils staying away from classes” calculating the attendance at Freedom Schools to be between “90,000 and 100,000.”[21] There were accounts of lessons being led by community educators in religious institutions, recreational spaces, and homes of volunteers. Students who regularly attended class in an NYC school building had complaints of “water overflowing from the toilets” and “rats in the cafeteria”, recognizing that it was the first time they’d received a quality education in sanitary spaces.[22] This article was one of the few in which the deplorable conditions plaguing New York City’s public schools were mentioned.

Leonard Budner reported “3,357 of the 43,865 teachers who were employed by the city were absent on Monday, nearly three times the usual number.”[23] Even with threats from Superintendent Donovan that “We don’t pay people to march around,”[24] many teachers were spending their day at Freedom Schools teaching a curriculum of African American history and civics, both curated and distributed by the Harlem Parents Committee.[25] By spending the day teaching without pay or recognition in makeshift schools, teachers were drawing attention to the desperate conditions in African American and Puerto Rican schools. Instead, the Times focused on the criticisms given by Superintendent Donovan, who said that all teachers would receive an “official warning” if they “[26]

By understanding the New York Times’s criticism of the local movement, we are better informed of the structural, societal and ideological barriers that activists faced when attempting to secure an equal and integrated education. With extensive criticism and a lack of moral support, we see how the New York Times chose to support the struggle in the South but became a foe to the activists, children and parents of the movement in New York.

Ethan Scott Barnett is a PhD student in History at the University of Delaware where he studies 20th century African American history, with a focus on the Jim Crow North and West. He can be reached on twitter at @EthanScottBarn.

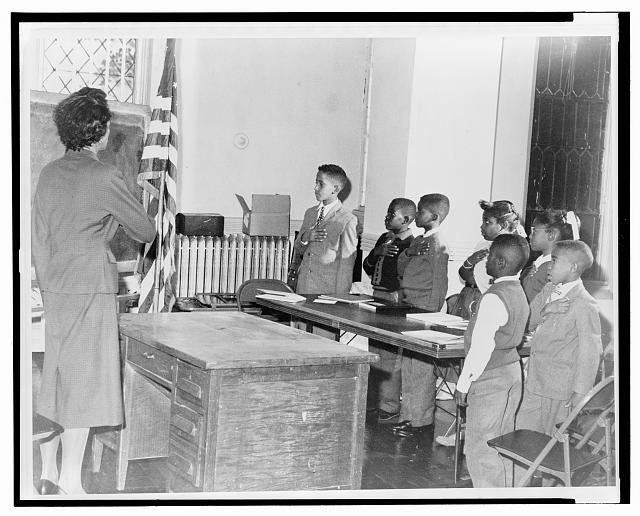

Image at top: Mrs. Claire Cumberbatch, of 1303 Dean St., leader of the Bedford-Stuyvesant group protesting alleged “segregated” school, leads oath of allegiance, Dick DeMarsico, September 12, 1958, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

[1] Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff, The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle, and the Awakening of a Nation (New York: Knopf, 2006), 407.

[2] Clarence Taylor, Civil Rights in New York City: From World War II to the Giuliani Era (New York: Fordham University Press, 2011), 96.

[3] “A Boycott Solves Nothing” NYT (Jan 31, 1964).

[4] Clarence Taylor, Civil Rights in New York City: From World War II to the Giuliani Era (New York: Fordham University Press, 2011), 96.

[5] Ibid, 95.

[6] “Man in the News” NYT (Feb 4, 1964)

[7] “Picket Line Organizer” NYT (Feb 2, 1964)

[8] Fred Powledge, “Leaders of Protest Foresee a New Era of Militancy Here” NYT (Feb 4, 1964).

[9] Ibid.

[10] “The School Boycott” NYT (Feb 4, 1964).

[11] “No More School Boycotts” NYT (Feb 3, 1964).

[12] Fred M. Hechinger, “Education School Boycott” NYT (Feb 2, 1964).

[13] Homer Bigart, “Thousands of Orderly Marchers Besiege School Board’s Offices” NYT (Feb 4, 1964).

[14] Fred Powledge, “Leaders of Protest Foresee a New Era of Militancy Here” NYT (Feb 4, 1964).

[15] McCandlish Philips, “Many Clergymen and Educators Say Boycott Dramatized Negro’s Aspirations” NYT (Feb 4, 1964).

[16] Ibid.

[17] Peter Kihss, “Many Steps for Integration” NYT (Feb 4, 1964).

[18] Ibid.

[19] “Boycott Cripples City Schools” NYT (Feb 4, 1964).

[20] Ibid.

[21] Robert Trumbull, “Freedom School Staffs Varied but Classes Followed Pattern” NYT (Feb 4, 1964).

[22] Ibid.

[23] Leonard Buder, “Move to Mediate School Dispute in City is Rebuffed” NYT (Feb 5,1964)

[24] Ibid.

[25] Robert Trumbull, “Freedom School Staffs Varied but Classes Followed Pattern” NYT (Feb 4, 1964).

[26] Leonard Buder, “Galamison Group Modifies Position on a New Boycott” NYT (Feb 19, 1964).

2 thoughts on “The New York Times and the movement for integrated education in New York City”