I am not exactly the world’s most cosmopolitan traveler. I never got on a plane until I was twenty years old, and I’ve only really visited a handful of countries. When my wife and I decided to go to Mexico City for a week this Fall, we went into it with some unwarranted assumptions. The biggest city in the Western hemisphere, we thought, would likely be a dense, chaotic metropolis akin to Karachi or Bangkok. The stereotype of the overcrowded and congested Third World city loomed large in our minds, and Mexico City seemed like it would fit that pattern.

Evidently, we were not alone in our assumptions. As journalist David Lida recalled in his 2008 book First Stop in the New World: Mexico City, The Capital of the 21st Century:

I was afraid of the capital, influenced by the propaganda dismissing it as a teeming, overpopulated, polluted bedlam, full of horrific testimonies of insuperable poverty. I imagined the armless beggars of Calcutta brandishing their stumps in tourists’ faces, hoping the display would result in a handout.

As it turns out, our expectations were very far from the truth. The small slice of Mexico City that we saw, in any case, was affluent and orderly compared to, say, Karachi. Undoubtedly much of Mexico is poor and rural, but the capital appeared to lack the evident and inescapable signs of extreme poverty that one finds in other megacities of the developing world. (As Lida points out, the city “has eighty-four hundred people per square kilometer, while Mumbai, Lagos, Karachi, and Seoul have more than double that figure.”) There were beggars and homeless people, of course, but one finds as many or more in American cities like New York or San Francisco.

The foremost financial and cultural center of Latin America was more distinguished by other hallmarks–those of capitalist prosperity and gleaming skyscrapers, gentrification and hip urbanism, tourism and historic preservation. Indeed, more late model cars clogged its crowded highways than we see at home in Atlanta, a sign of growing affluence, at least, among the population of the urban core, if not the poorer districts that surround the capital.

A few scattered observations of the city:

A mind-bogglingly extensive and accessible public transit system, that stretched over a vast urban landscape encompassing as many as 20 million people.

A remarkable predilection for PDA (public displays of affection), with couples kissing, groping, and practically dry-humping everywhere from escalators to subway cars to Starbucks.

Lots of pizza places.

A rich history as a destination for artists, writers, and political radicals, from Gabriel Garcia Marquez to Leon Trotsky.

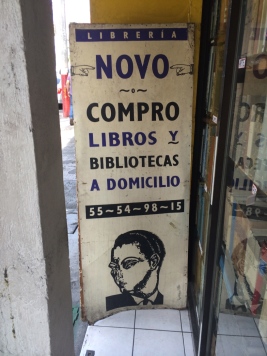

A large number of bookstores and even a surviving Blockbuster Video.

Bootleg media, albeit seemingly not as prevalent as in many Asian cities.

A visible legacy of radicalism, embodied in the ubiquitous paintings of Diego Rivera and other artists who contributed leftist depictions of class, race, and historical struggle to the nation’s iconography and mythology–as well as contemporary graffiti denouncing the murder of 43 students at the hands of government authorities and crime syndicates in 2014.

The utterly comprehensive embrace of American popular culture–fashion, food, entertainment, and technology–by the urban middle class (if not necessarily everyone else), in a way that surpasses even the zeal for all things American in South Asia. The affluent shopping mall we visited in Coyoacan/Copilco featured every American brand imaginable, from Skechers to Burger Fi to Quizno’s, with few local or national retailers to speak of. (“While foreigners here, principally Europeans, complain about the proliferation of Starbucks and Wal-Marts,” Lida notes, “middle-class Mexicans revel in the First World status bestowed by these establishments.”)

And while notions of race, class, and ethnicity clearly function differently in Mexico than the United States, it was impossible to miss a gradation of economic inequality shading from European to indigenous ancestry. In the most lavish new shopping malls, consumers were overwhelmingly fair-skinned and middle-class, sporting designer clothes from America and Europe. In the metro (disdained by some affluent residents as a form of transit), darker faces were numerous–except, of course, in the nicer, newer train line (the one that had air-conditioning) where we noticed (surprise!) whiter ones.

In the end, we found a profoundly beautiful and varied built environment, from the grand Baroque structures of Zocalo, the historic downtown district, to the Spanish colonial architecture of Coyoacan and San Angel to the more contemporary commercial landscape of the city’s younger neighborhoods. Like New York–the metropolis that Mexico City most reminded me of–a visit of a week is far too brief to get a sense of its vast and heterogenous social geography. But, as the great urban historian Ken Jackson once said, you don’t have to drink the ocean to know it’s salty. Here is a brief taste of the sights and textures of the capitol of Latin America, as seen from Copilco looking out.

Alex Sayf Cummings is an associate professor of History at Georgia State University. His work deals with media, law, and the political culture of the modern United States. He has previously received a Consortium for Faculty Diversity fellowship, an ACLS-Mellon postdoctoral fellowship, and the American Baptist Historical Society’s Torbet Prize, among other awards. His work has appeared in Salon, the Brooklyn Rail, the Journal of American History, Technology and Culture, HNN, Pop Matters, OUP Blog, Al Jazeera Americaand the edited volume Sound in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction from the University of Pennsylvania Press. His first book, Democracy of Sound: Music Piracy and the Remaking of American Copyright in the Twentieth Century, was published by Oxford University Press in 2013. He is the Senior Editor of the blog Tropics of Meta.

2 thoughts on “Metropole Travelogue Part I; Ciudad de Oro y Plata: Impressions of Mexico City”