By DeAnza A. Cook

Editors Note: This post, part of our Disciplining the City series, expounds upon the central thesis of “The Mass Criminalization of Black Americans: A Historical Overview” and examines the development of anti-black punitive traditions in American policing that first surfaced in the era of slavery and settler colonization.

An English court order mandating that “Watches be set at sunset” established colonial America’s first police patrol, the Boston Night Watch, on April 12, 1631.[1] Empowered by law to fine and whip perpetrators of civil disorders and property crimes, the watch was conceived as a paramilitary unit manned by an officer and six patrolmen. In 1636 a citizen-staffed watch augmented police manpower by demanding the routine participation of “every able-bodied man of the town” in a wide range of municipal services from firefighting to animal control.[2] Wealthier Bostonians, unwilling to comply with the new regulations, were compelled to designate suitable substitutes to serve in their steads. The court-ordered constitution of the Boston Night Watch was not an isolated phenomenon. The Dutch town of New Amsterdam soon followed suit in 1652, legislating a citizens’ “rattel wacht.” Urban laborers built watch posts across the city, and unpaid watchmen carried around rattles to alert each other during duty. By the end of the seventeenth century, comparable night watches and military guards had emerged in commercial settlements from Philadelphia to Charles Town to preserve the prevailing colonial order.

The expansion of African slavery and transatlantic trade routes fundamentally influenced the fabric and functions of policing throughout colonial America. Pursuant to their legal decree to “keep the peace,” northern watchmen were required to not only pursue “knaves, thieves, and burglars, of their own kith and kin,” but also to “keep tabs” on indentured servants, free and enslaved Blacks, as well as so-called “straggling Indians, who paid nocturnal visits from the wilderness.”[3] As white settlers in the Virginia, Carolina, and Georgia colonies bought enslaved Black people from Dutch traders and Barbadian planters in the Caribbean, they shared and adapted preexisting English and Spanish laws for organizing posses and mobilizing militia groups to capture runaway slaves and surveil plantation properties. Pervasive fears of Black rebellion fueled the creation of statewide curfews and comprehensive slave codes, which included the enforcement of a slave pass system.[4] Municipal rules authorized bands of wealthy, slave-holding, and “poor, slaveless,” white men to explicitly target enslaved persons traveling “in the night time without written permission [or pass] from their owners, masters, or mistresses.”[5] In response to recurring slave uprisings, such as the Stono Rebellion of 1739, local law enforcement authorities experimented with myriad slave patrol models and steadily financed an expansive infrastructure of city watchhouses and armed forces ready to defend the colonies from internal enemies and foreign threats by land and sea.[6]

State legislatures and local courts in Virginia and the Carolinas gradually elected to pay their patrolmen for twenty-four-hour tours of duty throughout the eighteenth century.[7] From their inception, slave patrolmen worked as deputized agents of social control in scattered countrysides and crowded city streets. Charged with controlling the burgeoning population of enslaved Black Americans, patrolmen were permitted to beat and whip “unruly” enslaved men, women, and children, as well as ransack slave dwellings in search of illegal contraband, weapons, and educational materials. Slave patrols, however, were not a distinct aberration from northern constable-watch systems. In fact, the passage of federal fugitive slave acts from 1793 to 1850 conscripted local and state law enforcement agents throughout the northern, southern, and western territories to participate in the capture and confinement of self-emancipated Black Americans. Slave management was indeed a core function of early American policing at the municipal, state, and federal level.

The deployment of police patrols during the revolutionary and antebellum periods engendered an enduring feature of American criminal law enforcement: an anti-black punitive tradition defined by “the habitual surveillance and incapacitation of racialized individuals and communities.”[8] Most recently, Elizabeth Hinton and I argued in the Annual Review of Criminlology that the roots and contemporary remnants of anti-black punitive traditions in American criminal justice first emerged in full force during slavery and settler colonization.[9] While most Black Americans were closely monitored and contained within a “carceral landscape” of rural plantations and urban workhouses, city jails controlled by town marshals and county sheriffs frequently functioned as convenient warehouses for holding, punishing, and selling enslaved Blacks at the whims of white owners and prospective buyers.[10] Targeted policing practices ensnared a constellation of enslaved, free, and fugitive communities within and beyond European colonial borders. Anti-black order maintenance functions were analogously deployed against Indians and Mexican migrants, and ultimately incorporated by police forces in the nineteenth century. As western settlers encroached into Indian Country and fought “savage wars” against Native Americans, law enforcement officials in Texas organized small militia companies in 1823 to carry out “mounted scouting and patrol duties” and man the border “against Mexicans as well as Indians.”[11]

Forty years prior to Robert Peel’s famous Principles of Law Enforcement in 1829, local law enforcement officials based in Charleston and New Orleans led the way in crafting the country’s first salaried “military-style” city guards.[12] The Charleston Watch originated in 1783 to surveil the city’s substantial concentration of slaves and expanded to include a hundred municipal and state policemen who patrolled plantation roads and industrial areas on foot and by horse by 1831.[13] New Orleans debuted its own paramilitary police force as early as 1805.[14] From the 1780s onward, leading up to the Civil War, urban uniformed units in the Deep South buttressed the extensive slave patrol network, supplemented by slave-holding families, plantation overseers, and state militia reinforcements, in addition to privately hired, slave-catching, bounty hunters. As racial and ethnic conflicts peaked in the 1830s, Crescent City authorities demilitarized and reorganized the New Orleans police to include Irish immigrant recruits and even “a few free African American men.”[15]

Yet, police work in the antebellum period required patrolmen, regardless of race or ethnicity, to regulate the behaviors, mobility, and livelihoods of enslaved Black Americans. “Free men of color” employed by the New Orleans city guard in 1805 served alongside majority-white militia groups and under the exclusive command of white officers, including Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815.[16] Charles Allegre and Constant Michel were among the first Black policemen recruited to the city guard in 1814, and Ellidgea Poindexter and Douglas C. Butler also served as “turnkeys in the city jail.”[17] The city’s pioneering Black policemen actively participated in anti-black police counterinsurgency operations. Most notably, they aided the suppression of the largest slave insurrection in the nation’s history, waged in St. Charles and St. John the Baptist parishes in 1811.

Within a racist society that overtly undermined political and economic freedoms and curtailed access to citizenship, some free people of color, fortunate enough to acquire wealth and social standing, regarded city police jobs as prestigious and “privileged” positions.[18] During Radical Reconstruction, Republican officials recruited Black policemen from Jackson, Mississippi, to Jacksonville, Florida, in defiance of Black Codes swiftly passed by former Confederate states. After 1877, however, only a select few Black men were permitted to work in the nation’s newly-emerging police departments. The Boston Police Department took on its first African American patrolmen, Horatio J. Homer in 1878, but it would be 140 years until the appointment of the city’s first Black police commissioner.[19]

Although modern police professionalization is generally associated with the early twentieth century, state laws and urban police reform efforts in the mid-nineteenth century laid the foundation for anti-black law enforcement strategies carried out by professional police departments in the Jim Crow era. Police historians often credit New York City for introducing the earliest “prevention-oriented police force,” loosely patterned after the London Metropolitan Police department, in 1845.[20] However, the New York City Police underwent a decade of administrative reorganization from 1843 to 1853 before fully transitioning to a uniformed professional police force and replacing the city’s constabulary and night watch system with “800 salaried, full-time officers.”[21] Unlike New York, the Massachusetts legislature had already passed a law “allowing the mayor [of Boston] and the board of aldermen to appoint daytime police officers” in 1838.[22] On May 21st, the municipal board appointed six officers to the Boston Police Department to serve under the command of the city marshal. The Boston Police coexisted with the Boston Watch as an entirely separate institution, until the state legislature permitted the city council to merge the watch and the police on May 26th, 1854.[23]

The refounding of the Boston Police was remarkably expedient and timely. Two days prior to the city council’s consolidation of the Boston Watch and the Boston Police, Deputy U.S. Marshal Asa O. Butman (a former Boston policeman) arrested 19-year-old Anthony Burns, a self-emancipated Black American and “fugitive stowaway” from Virginia.[24] While Burns remained confined in a Boston courthouse on the night of May 26th, 1854, local abolitionist Reverend T.W. Higginson led a crowd of enraged Bostonians to storm the building, killing a guard in the process. They demanded that Burns be freed immediately, and in response federal authorities implored the mayor to summon “two companies of militia to prevent further riot” in the city.[25] On June 2nd United States Commissioner Edward G. Loring gave the order to “send Burns back to slavery.”[26] Later on that same day a massive escort of “roughly two thousand uniformed men” marched Burns to the Boston harbor, and among them were 200 Boston policemen leading the way to “clear the streets ahead of the soldiers.”[27]

Muslim Justice League, “#StopCVE Now,” Fact Sheet, May 2020, Boston.

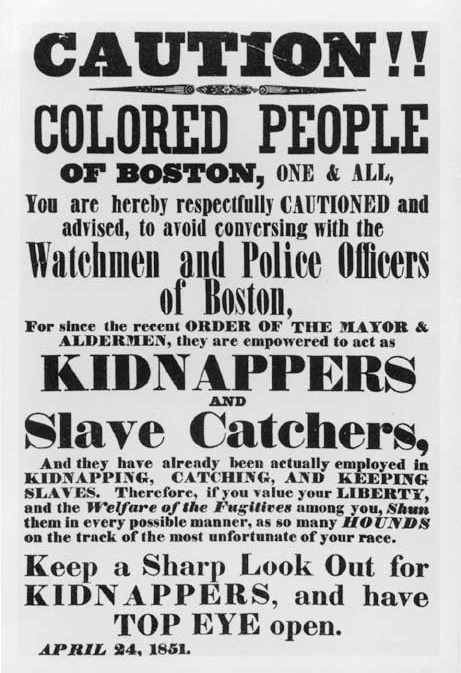

The detainment and deportation of Anthony Burns was one case in a series of violent struggles that unfolded between Boston abolitionists, Boston police, and federal law enforcement officials following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Three years before Burns’s botched escape to Boston, deputy marshals detained a self-emancipated man named Shadrach in a federal courtroom on February 15th, 1851.[28] A month later, seventeen-year-old Thomas Sims from Savannah, Georgia, faced the same fate—at the hands of arresting Officer Butman—the same man who later incarcerated Anthony Burns.[29] Boston police and militia forces jointly manned Sims’s “final march” from the courthouse to Boston Harbor on April 12th, 1851, but this time the Boston police had proactively “drilled with borrowed United States sabers,” marking the police department’s “first official experience with weapons other than the customary short club.”[30] Both arrests outraged abolitionist organizers with the Boston Vigilance Committee. In retaliation, on April 24th, they published placards denouncing Boston police officers as “Slave Catchers” and “Kidnappers.”[31]

From police patrols to police counterinsurgency operations, colonial and antebellum law enforcement officers labored to maintain existing race-based notions of social order under color of law. Abolitionists in the 1850s condemned the involvement of the Boston police in federal fugitive enforcement and incarceration in a similar way to how Bostonian abolitionists today are mobilizing against “white supremacist violence” and Obama-era CVE (Countering Violent Extremism) “community policing” programs in the city’s Muslim and Black Muslim American neighborhoods.[32] This fraught and variegated throughline in early American police history underscores the pervasive manifestations of anti-black racism in police law and police work.[33] Above all, it demonstrates that policing strategies and carceral tactics in this period cannot be divorced from an abiding anti-black punitive tradition that endures in the age of mass incarceration and the movement for Black lives.

After graduating from the University of Virginia in 2017, DeAnza A. Cook began her doctoral studies at Harvard University as a Presidential Scholar. Cook’s forthcoming dissertation traces the rise of proactive “community-oriented” and “problem-oriented” policing in Greater Boston and beyond in the post-Civil Rights era. Her work examines the role of the police, police partners, and African Americans in revamping police business and police-community relations at the dawn of the twenty-first century.

Cook is a Harvard Mellon Urban Initiative graduate fellow and a research fellow with the Center for American Political Studies. In addition to her doctoral studies, she is a “Civil Rights and Constitutional Policing” course administrator for law enforcement officers in her home state of Virginia, as well as an African American History instructor for incarcerated students at MCI-Norfolk.

Featured image (at top): “Caution!! Colored people of Boston, one and all…” Boston, 1851. Printed Ephemera Collection, Portfolio 60, Folder 22, Library of Congress.

[1] Bryan Vila and Cynthia Morris, The Role of Police in American Society: A Documentary History (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1999) 6-8. The English colonial court, based in Boston, comprised “Governor John Winthrop, Deputy Governor Thomas Dudley, and their assistants.” According to Francis Russell, they carried out the court order on April 12, 1631, and “two days later, as set down in the spidery handwriting of the record, ‘we began a Court of Guard upon the Neck, between Roxburie and Boston, where upon shall always be resident an officer and six men.’” Francis Russell, A City in Terror: Calvin Coolidge and the 1919 Boston Police Strike (Boston: Beacon Press, 1975), 26.

[2] Vila and Morris, The Role of Police in American Society, 6-8. Citizen watchmen performed a variety of municipal tasks, including fire control, weather updates, and responding to wandering wolves and bears that threatened to “carry off young kids and lambs.”

[3] Vila and Morris, The Role of Police in American Society, 6-8.

[4] Sally E. Hadden, Slave Patrols: Law and Violence in Virginia and the Carolinas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2003), 60-61, 190.

[5] Hadden, Slave Patrols, 60.

[6] Alan Taylor, The Internal Enemy: Slavery and War in Virginia, 1772-1832 (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2013); Ryan Fontanilla, “Immigration Enforcement and the Afterlife of the Slave Ship,” Boston Review, (February 11, 2021) http://bostonreview.net/race/ryan-fontanilla-immigration-enforcement-and-afterlife-slave-ship.

[7] Hadden, Slave Patrols, 30-39. Military-style law enforcement models in the slave-holding societies represented the earliest iterations of paid police patrols in America. See also, Dennis Rousey, Policing the Southern City: New Orleans, 1805-1889 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1996) 4.

[8] Elizabeth Hinton and DeAnza Cook, “The Mass Criminalization of Black Americans: A Historical Overview,” Annual Review of Criminology 4 (January 2021): 263.

[9] Hinton and Cook, “The Mass Criminalization of Black Americans,” 261-286.

[10] Walter Johnson, River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017); Stephanie M. H. Camp, Closer to Freedom: Enslaved Women and Everyday Resistance in the Plantation South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004).

[11] Vila and Morris, The Role of Police in American Society, 29. Vila and Morris state that “beginning with Texas’ successful struggle for independence from Mexico in 1835, and continuing during the period of the Texas Republic from 1836 to 1845, the role of the Rangers was expanded to include guarding the Texas border against Mexicans as well as Indians. After Texas joined the Union in 1845, the Rangers also served as a ‘mobile striking force’ during the Mexican War of 1846-1848 that followed.” For the origins and accounts of “savage wars,” see Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz, Loaded: A Disarming History of the Second Amendment (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2018).

[12] Rousey, Policing the Southern City, 4.

[13] Alex S. Vitale, The End of Policing (Brooklyn: Verso, 2017), 46-47.

[14] Rousey, Policing the Southern City, 6.

[15] Rousey, Policing the Southern City, 7. Rousey ascertains that “at least a few African Americans served on the force up until 1830, but apparently none could obtain such appointments during the period of 1830-1867. Once slavery had been abolished, black New Orleanians sought access to many opportunities formerly denied to them, including places on the police force,” but many Black policemen were purged from the ranks after the Civil War and the New Orleans’s city guard curbed Black male recruitment to the force by 1870.

[16] W. Marvin Dulaney, Black Police in America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 8-9.

[17] Dulaney, Black Police in America, 10.

[18] Dulaney, Black Police in America ,9.

[19] Gal Tziperman Lotan, “Boston’s first black police officer honored,” Boston Globe, January 06, 2013, https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2013/01/06/boston-police-community-room-dedicated-first-black-officer/DurbL4puDOrjo5TDNXZg4N/story.html?event=event12; Massachusetts Association of Minority Law Enforcement Officers, Inc. (MAMLEO), “Police officers bowed their heads during a prayer after the ceremony naming a room in the Dudley Square station for Sergeant Horatio J. Homer,” http://www.mamleo.org/horatio-j-homer.html. The sporadic hiring and piecemeal promotion of Black policemen, and later Black policewomen, prevailed during the “Progressive era” of federal Prohibition and statewide Jim Crow law enforcement. Major transformations for Black Americans in law enforcement would not surface en masse until the aftermath of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement with the advent of court-ordered consent decrees and affirmative action plans for police departments throughout the nation.

[20] Vila and Morris, The Role of Police in American Society, 35-36. Wilbur R. Miller highlights that “New York City’s Municipal Police Act, put into effect in 1845 after several years of political wrangling, created the first police force modeled on London’s precedent outside of the British Empire.” For more about the London Metropolitan Police and New York Police, see Wilbur R. Miller, Cops and Bobbies: Police Authority in New York and London, 1830-1870, 2nd ed., (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1999), 2-3.

[21] Vila and Morris, The Role of Police in American Society, 36. After visiting London in 1852 to observe the “efficiency” of the London police, Eric Monkkonen explained, New York official “James W. Gerard presented a closely reasoned argument for reorganizing and uniforming the New York police in early 1853.” According to Monkkonen, “the complete transition from the constable-watch system to the uniformed police took two decades in Boston, 1838-59; a decade in New York, 1843-53; and eleven years in Cincinnati, 1848-59.” See, Eric H. Monkkonen, Police in Urban America: 1860-1920 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), 41-42.

[22] Russell, A City in Terror, 29-30.

[23] Russell, A City in Terror, 30-31. Following the consolidation of the Boston Watch and the Boston Police Department in 1854, Francis Russell remarked, “the 229-year-old Boston Watch and Police ceased to exist and the Boston Police Department came into being. The new department, with headquarters at City Hall, had a chief, two deputies, a superintendent of hacks, a superintendent of teams, and five detectives. Eight police stations divided up the whole territory of the city, each with a captain, two lieutenants, and anywhere from nineteen to forty-four patrolmen.”

[24] Roger Lane, Policing the City: Boston, 1822-1885 (New York: Atheneum, 1971), 90.

[25] Lane, Policing the City, 91.

[26] Lane, Policing the City, 91.

[27] Lane, Policing the City, 91. According to Lane, “the [Boston] police were called in on June 2…it was the job of the police, about two hundred in all, to clear the streets ahead of the soldiers so that Burns could be marched to the harbor and Richmond.”

[28] Lane, Policing the City, 72. On February 15th, 1851, Lane recounts that “fully nine Deputy United States Marshals arrested the escaped slave Shadrach in Cornhill coffee shop, in full view of the patrons.” Thereafter, “Shadrach was confined in the federal courtroom” and “when a writ of de homine replegniando and petition of habeas corpus were both denied, a crowd of free Negroes stormed the courtroom and carried Shadrach to safety.”

[29] Lane, Policing the City, 73-74. Notably, “[Sims] was first told that he was being arrested for theft. When he became suspicious and resisted, he managed to stab Officer Butman seriously with his knife.” However, Sims was eventually restrained and “locked up on the third floor of the courthouse.”

[30] Lane, Policing the City, 74. When Sims’ allies finally arrived at the courthouse, “the building was surrounded by a guard consisting of every patrolman on the force, day and night men both.” Ultimately, “Sims was marched off on April 12 with a police and militia escort, the first fugitive ever successfully returned from the city.”

[31] Lane, Policing the City, 73.

[32] Muslim Justice League, “#StopCVE Now,” Fact Sheet, May 2020, Boston, https://muslimjusticeleague.org/cve/. The Muslim Justice League or “MJL” was formed by four Muslim women in Boston in 2014, in response to a pressing need for local Muslim-led defense of our communities’ human and civil rights against the ‘War on Terror.’” To learn more about Muslim Justice League, visit https://muslimjusticeleague.org/our-work/.

[33] At the conclusion of her introduction to the seminal text, Golden Gulag, carceral geographer and prison abolitionist Ruth Wilson Gilmore arguably provides the most robust and theoretically rich definition of racism to date: “Racism, specifically, is the state-sanctioned or extralegal production and exploitation of group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death.” In essence, racism is not reducible to molecular feelings of prejudice, but rather anti-black racism, in particular, reproduces systemic disparities in the distribution of land, labor, and life-affirming resources. According to Gilmore, all too often anti-black racism manifests in the form of “catch-all” geographic and political-economic solutions (i.e. the prison) for controlling and incapacitating so-called “surplus populations.” See, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Golden Gulag: Prisons, Surplus, Crisis, and Opposition in Globalizing California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 28.

One thought on “Anti-Black Punitive Traditions in Early American Policing”