Editor’s note: This is the fifth entry in our theme for May, Cities of the Eastern Mediterranean.

by Francesco Anselmetti

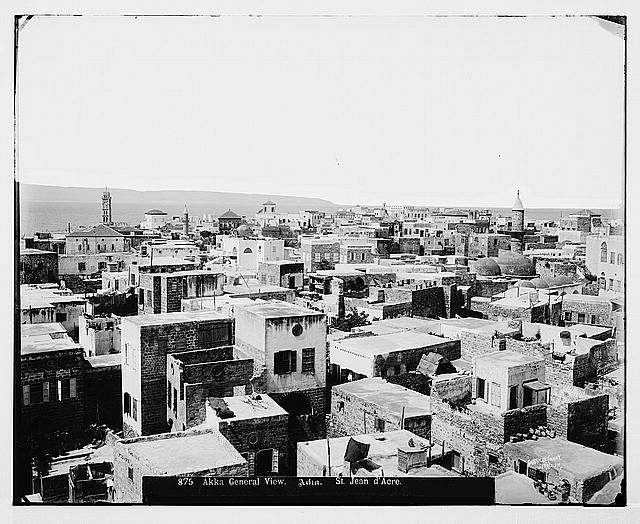

Entering ‘Akka in November 1693, ‘Abdel Ghani al-Nabulsi was overcome with disappointment. “We arrived at ‘Akka—a ruined town”, the Damascene intellectual writes, “its walls destroyed, the eye of its castle gouged out, the fruits of its industry absent. A few houses remain here and there: bundles of sticks of little consequence.”[1] Al-Nabulsi could perhaps be forgiven for his high expectations. Having no doubt read the triumphal accounts of the Mamluk reconquest of the Crusader capital of Acre in 1291—which had put a definitive end to Frankish presence in the Levant—he likely hoped to find traces of ‘Akka’s former splendor as he passed through the city on his way to Egypt. Not even the great tower built by the Sultan al-Ashraf Khalil to cement his conquest over Christendom was left standing, let alone the numerous buildings that had given the medieval port its distinctive character: the Gothic Church of St. Andrew; the Pisan Harbor; the Genoese fondaco; the Royal Customs House, which regulated the flow of merchant capital on which the Crusades themselves depended, and in turn aimed to secure.[2]

Had al-Nabulsi returned to ‘Akka a few decades later, he would have witnessed a rather different scene. By the time he made his journey in the late seventeenth century, the expansion of French commercial hegemony on the Syrian coast was already underway. For over a century, the port of Saida had functioned as the primary export hub for Syrian silk and cotton, grown on Mount Lebanon and Jabal ‘Amil, which had begun feed the growing textile industry of southern France, based around the port of Marseilles.[3] During al-Nabulsi’s lifetime (1641-1731), then, Ottoman regional power was concentrated in Saida, home to both representatives of the Porte and the consul in charge of the affairs of the French mercantile nation. In the early decades of the eighteenth century, though, the region experienced a dramatic shift: tribal elites from the highlands of the Galilee—from the clan of Zaydan in particular—who had been contracted by the imperial state as tax farmers for the immediate region came into open conflict with the Ottomans’ representatives in Saida. They led a series of rebellions, beginning in the 1730s, and ultimately succeeded in defeating the Ottoman governor at Saida, ruling for the following four decades with considerable autonomy from the central state. ‘Akka, offering a more proximate alternative to Saida as an entrepôt for growing cotton cultivation in the Galilee and crucially now removed from the fiscal purview of the central Ottoman state, served as their fortress and capital from the late 1740s. By the middle of the century, around half of the cotton imported to France from the Mediterranean passed through ‘Akka. Unsurprisingly, this was accompanied by a drastic and sudden transformation of the city’s urban fabric. In 1750, just a few years after the Zaydanis, under the leadership of Dahir al-‘Umar, had taken control of the city, its inhabitants numbered no more than 3,000—a fraction of its former size in the thirteenth century. In the space of just twenty years, travelers would estimate the city’s population at 25,000.[4] So successful were the Zaydanis in building this city-state, that successive regional governors, even if appointed by the Ottoman state to administer the provinces of Saida or Damascus, based themselves in ‘Akka well into the nineteenth century.

How to take stock of the century (1730-1830) in which ‘Akka came to dominate the Syrian coast? The story is certainly a political one. However tenuous the claim may be, the popular conception of the city as the capital of the first autonomous Arab state in Palestine is not entirely groundless.[5] But ascribing national characteristics to an autonomous imperial province, which so obviously evades more typical categorizations of independent statehood, imperial dominion, or colonial possession, risks betraying the very reason the city and the period merit study. How was the city’s function as the seat of an autonomous regional state reflected in its reconstruction in the eighteenth century? Many have pointed to its monumental architecture as evidence for the rivalry between provincial governors based in ‘Akka and other regional potentates—perhaps even the imperial capital itself. The emblematic example here being the grandiose mosque of Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar, built in 1778.

But as enticing as these stories of intrigue and largesse may be, they offer little to our understanding of what may be more firmly identified as the city’s distinctive feature: its function as the primary site of mercantile capital accumulation on the Syrian coast in the eighteenth century and its role in integrating the broader region into the circuits of an increasingly global capitalist mode of production. This commercial wealth, of which the provincial state is commonly thought to be the primary beneficiary, perhaps more importantly came to be concentrated in the hands of a few powerful merchant families, a local oligarchy of sorts, of overwhelmingly Greek Catholic (Melkite) extraction. The descendants of this community—the sons of the Sabbaghs, the Bahris, the Farhis, the Mishaqas, to name a few—would go on to occupy positions of considerable power in the region over the course of the following century. ‘Akka, in no uncertain terms, was the crucible in which a sizable portion of a Levantine bourgeoisie was forged, one that would go on to dominate the political, economic, and intellectual life of semiautonomous Egypt and the reorganized Ottoman provinces of Lebanon and Syria.[6]

It is the reorganization of the city according to the logic of commercial activity—by no means new to the region, but certainly intensifying at unprecedented rates—that determined the nature and character of its urban space in the eighteenth century. ‘Akka’s expansion in the period was significantly mediated by its local government, more specifically by its policies (by no means consistent) of extracting revenue from the lucrative Mediterranean cotton trade for which ‘Akka had rather rapidly become a pivot. Would the local administration focus its efforts on being the sole mediator between cotton cultivators and French merchants, or would it more fruitfully focus its energies on negotiating customs tariffs to match the steadily increasing profitability of the trade? It is these types of decisions that determined government-sponsored building projects of commercial storehouses, markets, and port infrastructure. Since the historic center of the contemporary city of ‘Akka has largely preserved its urban arrangement from this period, it remains legible as a spatial testament to a locally specific trajectory of capital accumulation that significantly impacted the economic, political, and social development of the Syrian coast as a whole.[7] Extant accounts of the city in the period—overwhelmingly political histories—have relied almost exclusively on French mercantile correspondence, consular reports, and accounts of Arab chroniclers, since we lack the documentary evidence that ordinarily forms the bedrock of social and economic histories of the region. ‘Akka’s local court records, its sijillat, were probably lost in one of the city’s many sieges, the most destructive of which came in 1840 at the hands of the British Navy.

The city’s commercial infrastructure, its many markets and khans, as well as their arrangement in the city in relation to one another, has largely survived. It is on the latter typology, the khan, that I want to focus in what follows, as a way of sketching an approach that might provide useful insight into the reverberations of ‘Akka’s commercial expansion on the social life of the city and its inhabitants; the provincial state functionaries, Arab and French merchants, artisans, and shopkeepers; and perhaps most importantly the cotton cultivators who would come to town to market the fruits of the labor on which the city’s wealth depended. In its most general sense, a khan is a structure aimed at controlling commercial activity, though its function varies markedly over time and space. ‘Akka’s khans have far more in common with Venetian or Genoese fondachi than the caravanserais of Anatolia or Iran (the distinction here is between structures that link maritime rather than overland trade).[8] The structures were storehouses rented out by their owners (usually the state) to merchants, artisans, and peasants. They often also offered lodging for traveling merchants, as well as centralized marketplaces for the supervision of trade. Below is an elaboration of the differences between two such spaces of fiscal extraction and commercial control in ‘Akka: Khan al-Shawardeh, built under ‘Akka’s first autonomous government, and Khan al-‘Umdan, built by a successive autonomous ruler in the last decades of the eighteenth century (figure 1).

In the early decades of ‘Akka’s autonomy (1747-74), its governor, Dahir al-‘Umar al-Zaydani, faced a major challenge. The Galilee—the districts of Safad, Tiberias, and Nazareth amongst others—had emerged as the primary producer of quality cotton in the region, mobilizing French merchants in ‘Akka not only to break from the system of repartitions (price-fixing) set by the French vice consul in Saida, but also to penetrate the countryside themselves in order to buy cotton directly from the local peasantry. A primary goal of Dahir’s rule was to come between French merchant capital and the rural producer, monopolizing the cotton trade for the benefit of his state—thereby controlling its price—and, in parallel, controlling the revenues of ‘Akka’s customs houses.[9]

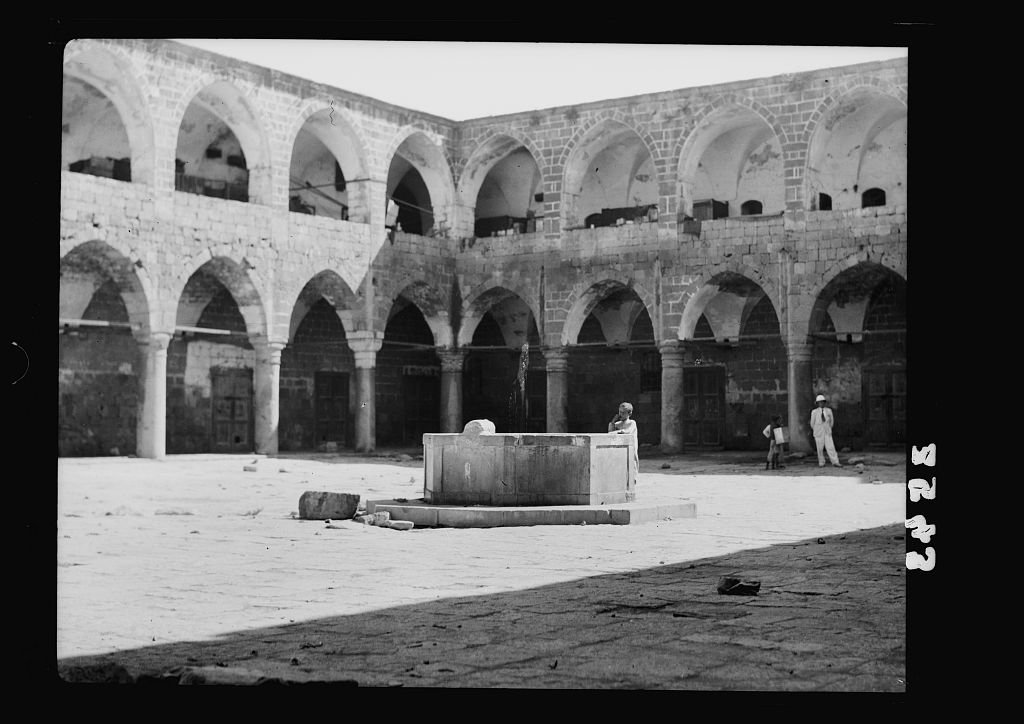

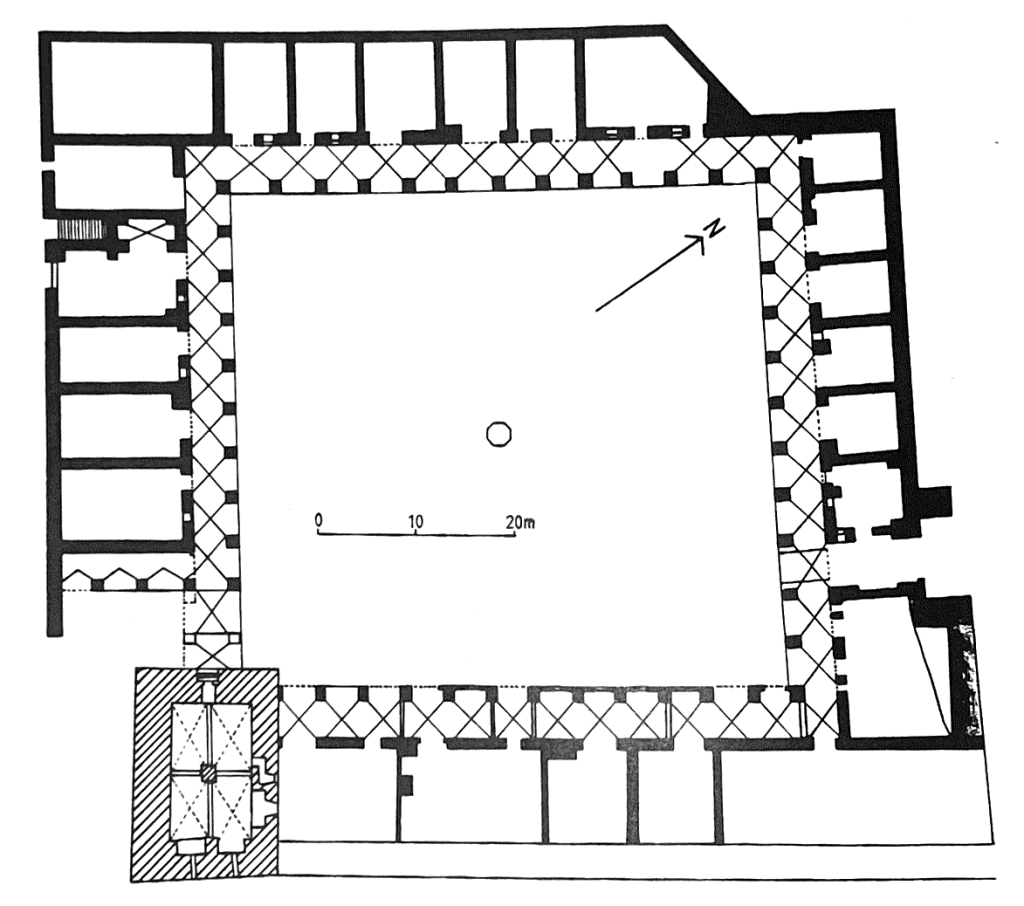

This specific economic imperative is legible in decisions made by Dahir’s government to redevelop ‘Akka’s commercial infrastructure. After taking the city in 1747, the governor launched a series of building projects: he refortified its walled defenses, built mosques, and reconstructed former Crusader buildings for his personal lodgings. His state also sponsored the construction of a khan in the northeastern corner of the old city, known as Khan al-Shawardeh (figures 2, 3). While its exact date of construction is difficult to establish, inscriptions date the structure beyond doubt to the time of Dahir.[10] Built on the site of a former nunnery, the khan is a large square structure organized around a central courtyard with two gateways, one in the southwest corner (now demolished) and one in the southeast. Each side of the courtyard is lined with a tall arcade composed of cross-vaulted bays resting on square piers. Behind the bays is a series of large-vaulted rooms, and in the center is an octagonal sebil. The khan was, most significantly, a few hundred meters away from the main land gate of the city.

Dahir was eventually liquidated by the Ottoman state in 1775, after his ill-fated decision to side with Russia in the Russo–Ottoman War of 1768-74. He was replaced as governor by Ahmed Pasha al-Jazzar (“the Butcher”), a Bosnian-born functionary in the Egyptian military-administrative ruling apparatus that had been sent to ‘Akka to reinstate Ottoman authority over Dahir’s autonomous state. Al-Jazzar used his newly acquired power to carve out a similar kind of autonomy that Dahir himself had enjoyed as ruler of ‘Akka. The Ottoman state appointed Jazzar vali of Saida, and then eventually governor of Damascus, but al-Jazzar chose to consolidate ‘Akka’s prominence, making it once again his capital. Along with his landmark mosque built in the 1780s, the most important building project undertaken by al-Jazzar was the reconstruction of a khan on the foundations of the Genoese fondaco by the harbor, known as the Khan al-‘Umdan (or Khan of the Columns, figure 2), a two-story structure built around a rectangular courtyard enclosed by two tiers of arcades. The arcade on the ground floor rests on red and black granite columns, with entrances on two of its four sides, a main gate in the middle of the north side, and two gateways to the south. Also of note is the annex to the building erected in 1813 by Haim Farhi, a Damascene Jewish merchant employed by al-Jazzar as his advisor and treasurer.

Several architectural features of the two khans may be compared to accentuate their differences in function and position within the broader network of the city’s cotton trade. Dahir al-‘Umar, a member of the local agrarian hierarchy that had emerged from within local peasant society, built a khan almost adjacent to the city’s only entrance by land—a way to ensure that incoming peasants, with their weekly loads of cotton, grain, and olive oil, would come under direct state supervision as soon as they entered the city. From the size and layout of Dahir’s khan, it would seem that this was a structure that could much more easily accommodate pack animals—resembling more a rural khan than its urban counterpart. Equally intriguing is the decision by al-Jazzar’s administration to develop a site more closely associated to the harbor and the customs house. Note, for instance, the absence of a second story in the Khan al-Shawardeh, a sign that the building’s function was not primarily to house or accommodate individuals. Moreover, the size of the lateral rooms (figure 3) suggest that they were spaces for the storage of goods rather than quarters for merchants. Also of note is the marked difference between the two sebils at the center of each structure. The fountain in Khan al-Shawardeh seems to have had a functional role providing water for animals arriving to the city from the countryside. The higher, less accessible marble casing of the fountain in the middle of the Khan al-‘Umdan suggests a more ornamental role in the courtyard, an aesthetic choice in harmony with its the use of marble column spolia along the ground floor—the khan’s distinctive feature and origin of its name. This was a space of a certain refinement, one reserved for transactions of a purely monetary kind between mercantile agents and the provincial state, abstracted and removed from the quotidian, laborious loading and unloading of goods that characterized the marketplace and harbor.

This much is clear, then: different commercial policies employed by ‘Akka’s successive governments in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries fundamentally shaped the organization of the city. Khans were deployed by city administrators as spatial traps to capture revenue from the city’s expanding trade in cotton. The social makeup of successive regimes dictated at what stage in the circulation of this commodity they chose to extract value. Dahir al-‘Umar, a Palestinian sheikh, exercised more direct control of the Galilean peasantry than Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar, a foreign upstart in the Ottoman military establishment, ever could; the latter chose to expand his state’s revenue by exerting pressure on trade at the point of export. But what is clear is that the arrangement of the city in the eighteenth century was not just designed to control the flow of commodities in and out of the city. It also represented an attempt by the local state to manage the mobility of different classes engaged in trade, and limit their access to one another for the purpose of exchange. What emerges is just an impression, one to be sharpened by further research, though in the absence of documentary evidence, the way in which this particular production of space structured and shaped the life of the city’s inhabitants can only meaningfully be reconstructed by using and thinking with what the city itself offers us: a rare spatial archive of an eighteenth-century Levantine commercial society.

To approach ‘Akka’s history spatially is not merely an analytical necessity. The city’s architectural heritage, most of which dates to the period in question, now forms the Old City of Akko, as the city came to be known after the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. Despite attempts to ethnically cleanse the city during the Nakba, the heart of ‘Akka remained—and remains to this day—predominantly Palestinian. For decades, its residents have been engaged in struggle against local conjugations of Israeli settler-colonialism: rapacious policies of gentrification, bent on transforming the city into a touristic Crusader fairground; a city out of time, allegedly unchanged since the medieval period—a show consciously and deliberately aimed at attracting European sightseers.[13] And what of the remnants of the city’s more recent past, such as the aforementioned Khan al-‘Umdan? A project, headed by Israeli developers, has been underway for some years now: the structure is to become the city’s premier boutique hotel, with access, of course, restricted to a paying clientele that is somehow to be shielded from the living, material testament to historical continuity they will temporarily inhabit.

Resistance to the commodification of ‘Akka’s architectural heritage is, crucially, about the right to the city in the face of sustained colonial dispossession—one that is articulated predominantly through the assertion of the traditional Arab or Palestinian “character” of the city’s structures. But the nature of the sites under contestation also reveal a secondary imperative: the struggle over the vestiges of ‘Akka’s commercial economy is also an invitation to reflect on their legacy—one that testifies to various forms of economic and social domination that were largely produced and enforced by local actors, well before the age of British and Zionist colonialism. Moreover, despite political imperatives to memorialize these local actors as moved by some kind of proto-nationalist sentiment, there is little evidence that the city’s economic autonomy was matched or justified by any claims of Palestinian or Arab sovereignty. All this may sit awkwardly with present political urgency of asserting national rights in the face of colonial rule, though it perhaps serves as further encouragement, as Sherene Seikaly has reflected, “to ask why that sufficiency and/or its lack continues to be the measuring stick for whether people can remain on the land they resided on for centuries.”[14] In its rise and fall as a commercial emporium in an age of intensifying capital accumulation on a global scale, ‘Akka did not, in the first instance, depend for its development on the more direct interventions of European imperialism that would characterize the region’s experience of the following century, but one that was already present at its arrival. The city asks us not merely to assert its early modernity against colonial erasure; it also requires us to reckon with the ambivalent legacy of its economic complexity, urban arrangement and class composition.

Francesco Anselmetti is a doctoral candidate in History and Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard University. His dissertation examines the formation of social classes and modern states in the Eastern Mediterranean over the course of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

Featured image (at top): “Beirut, etc. Akka” (ca. 1898-1914), Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

[1] ‘Abdel-Ghani al-Nabulsi, al-Haqiqa wa-l-Majaz fi Rihlat Bilad al-Sham wa-l-Hejaz (Damascus, 1989), 294.

[2] The shape of the different European states instituted in the Holy Land tended to reflect the political and economic order of their founders. While Frankish and English feudal lords tended to be interested in acquiring land, the Italian merchant republics sought to establish colonies in coastal cities so as to broaden their mercantile networks. For Genoa, Venice, Pisa, and Amalfi (the four Italian maritime republics), Alexandria was often the most lucrative destination, but with the Pax Mongolica the Syrian coast in the 13th century also began carrying considerable trade westward. See D. Jacoby, Travellers, Merchants and Settlers in the Eastern Mediterranean, 11th-14th centuries (Farnham, UK: Ashgate Variorum, 2014).

[3] For an account of the growth of an import-substituting textile industry in the French Mediterranean, see O. Raveux, “The Birth of a New European Industry: L’Indiennage in Seventeenth Century Marseilles” in G. Riello & P. Parathasarathi eds., The Spinning World: A Global History of Cotton Textiles, 1200-1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 291-306.

[4] For scale: reliable accounts for the population of Haifa, emblematic along with Beirut of the industrial Syrian port city in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, claim the city’s population in the late eighteenth century did not exceed 250. For a detailed discussion on the sources available for ‘Akka’s population in the eighteenth century, see T. Philipp, Acre: The Rise and Fall of a Palestinian City 1730-1831 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002), 193-196.

[5] Perhaps the most popular literary expression of this story is Ibrahim Nasrallah’s epic historical novel, centered on the life of Dahir al-‘Umar al-Zaydani, Qanadil Malik al-Jalil (2012), translated and published in English as The Lanterns of the King of Galilee (2014).

[6] These are elites that in their mobility should arguably be distinguished from the more rooted bourgeoisie of a city like Nablus, extensively documented by Beshara Doumani in his seminal Merchants and Peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700-1900 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995). A couple of examples, amongst many, of the careers of the sons of ‘Akkawi businessmen: Mikha’il Ibrahim al-Sabbagh, grandson of the cotton merchant and state functionary Ibrahim al-Sabbagh, worked as a key local intermediary during the Napoleonic occupation of Egypt (1798-99). He would later retreat with the French to Paris and pursue a career as a writer and historian. Hanna Bahri, son of Mikha’il Bahri, a poet and secretary to Ahmad Pasha al-Jazzar, worked as the head of the civil administration of Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha’s occupation of Syria (1831-40).

[7] My use of the term “trajectory of accumulation” over the more commonly-used framework of a “transition to capitalism” is informed by a distinction made by Jairus Banaji in “Trajectories of Accumulation or ‘Transitions’ to Capitalism?” Theory as History (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011), 333-349.

[8] For a brief discussion on the role of the fondaco in the history of capitalism, see J. Banaji, “Reading Capitalism Philologically: The History of the Fondaco” The Edition, Sept. 5, 2021.

[9] A useful survey of Dahir’s autonomous state, which includes a discussion of his development of ‘Akka, can be found in M. Yazbek, “The Politics of Trade and Power: Dahir al-‘Umar and the Making of Early Modern Palestine” in Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 56 (2013): 696-736.

[10] A. Petersen, A Gazetteer of Muslim Buildings in Palestine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 86.

[11] A. Cohen, Palestine in the 18th Century: Patterns of Government and Administration (Jerusalem: Magnes Press, Hebrew University, 1973).

[12] Thomas Philipp has published useful figures on ‘Akka’s trade, on both its volume and value, based on the records of the Marseilles Chamber of Commerce. See Philipp, Acre, 197-214.

[13] Mahdi Sabbagh provides a crucial synthesis of these policies, their relationship to ‘Akka’s architectural heritage, and the attempts by the city’s Palestinian inhabitants to resist them in a recent piece: “Dispossession in the Living City of Acre” PLATFORM, May 2, 2022.

[14] S. Seikaly, Men of Capital: Scarcity and Economy in Mandate Palestine (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2016), 4.