By David J. Goodwin

The young writer hunched over their desk in a cramped apartment, the morose poet scribbling in a notebook in a cafe, the frustrated playwright buttonholing a producer on the sidewalk, the cynical journalist waiting for a source in a seedy bar—men and women of letters belong to the narratives of cities embedded in the public imagination and immortalized across various artistic media. Cities themselves provide the raw materials for many writers, serving as rich settings, furnishing a ready cast of characters, and containing layered histories.

Certain authors and their creations are symbiotically bonded with their cities. They—both the writers and their fictions—become identified with a given locale, and vice versa. William Kennedy utilized his native Albany, New York, as the canvas for a series of novels published across nearly four decades. Throughout his career, Philip Roth mined his hometown of Newark, New Jersey, for his fiction. From the pens of talented chroniclers, chosen cities become breathing, sentient entities themselves. Two recent books, Dickensland: The Curious History of Dickens’s London by Lee Jackson and Balzac’s Paris: The City as Human Comedy by Eric Hazan, embrace distinctly different frameworks to explore the compelling dynamic between two metropolises and their storytellers.

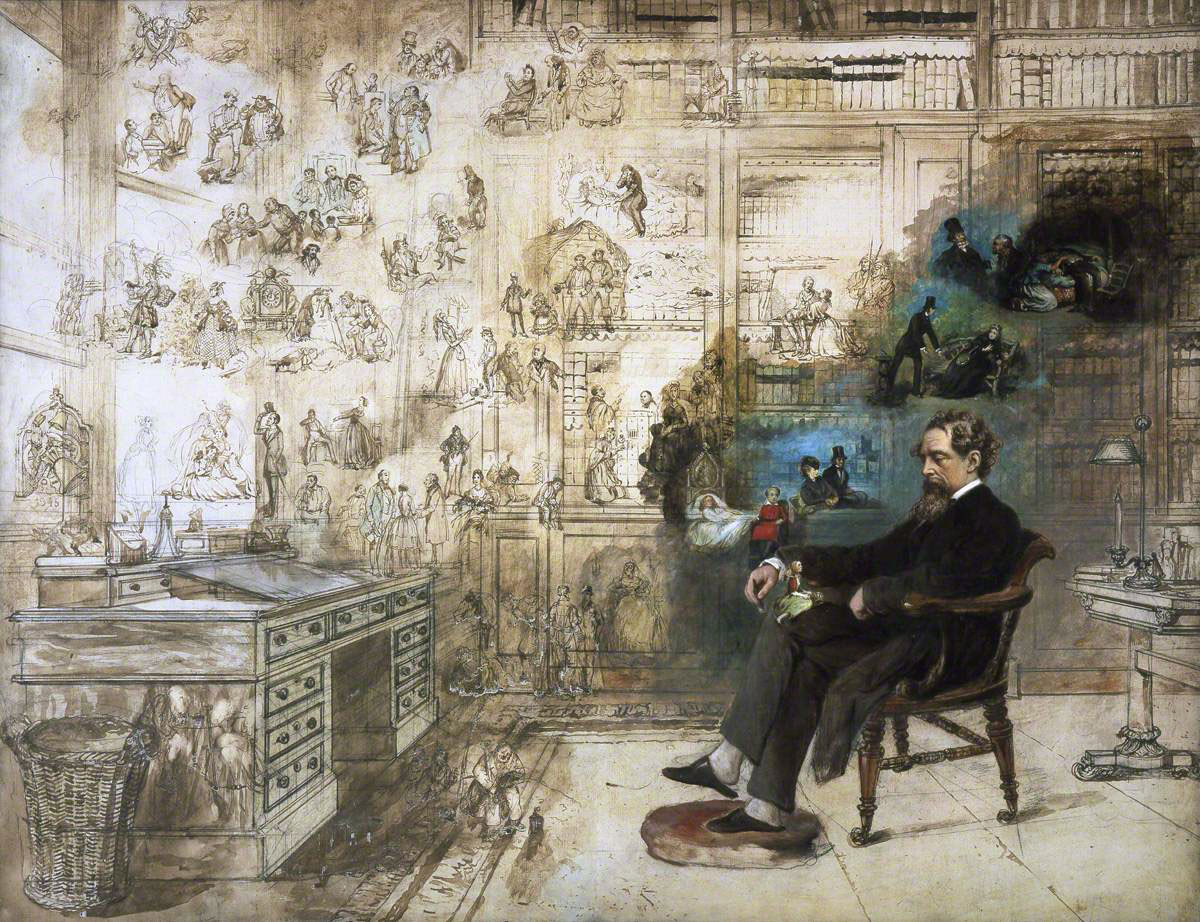

At the time of his passing in 1870, Charles Dickens was a beloved cultural figure in the United States and the United Kingdom with “a profoundly intimate connection” with his audience.1 Although his earthly remains are interred in the Poets’ Corner of Westminster Abbey, the creator of Great Expectations, David Copperfield, and Barnaby Rudge achieved “[l]iterary immortality” in no small part due to his imaginative mapping of London.2 The reading public exhibited a hunger to consume the sounds, sights, and smells—the historic texture, or a simulacrum of it—of Dickens’s London, fueling a boom in literary tourism which began before his death and continues into the present (my own visit to the British capital in 2024 with a colorfully illustrated map of locations and buildings that possibly inspired A Christmas Carol might stand as evidence of this activity). The phenomenon of literary tourism coupled with its encounters and effects on a specific locale stand as the central focus of Lee Jackson’s Dickensland.

Jackson builds his study by selecting specific geographic sites or spaces (or their facsimiles) popularized by Dickens and sought by his readers. Many of these structures were later demolished, leaving Dickens’s fictionalized sketches as quasi-historic records. Such vanished places include traditional stagecoach inns portrayed in The Pickwick Papers; Russell Court burial ground, a neglected, rodent-infested, yet never specified cemetery in Bleak House; and London Bridge, a “nexus of a weird and deathly metropolis” in Oliver Twist.3 These locations offer vehicles for exploring the impact of urban development and social progress on the very centers drawing literary tourists. Dickens’s legacy itself propelled these movements and thus threatened the “Old London” masterfully captured in his prose. Jackson demonstrates the manner in which Dickens’s vivid descriptions and captivating narratives of “the slum, the decrepit house, the narrow street” motivated civic reformers to erase such buildings and neighborhoods from London.4 Likewise, critics of redevelopment programs pointed to the “aesthetically and imaginatively rewarding” urban fabric portrayed in Dickens’s works as deserving to be spared from the forces of progress.5

The relationship between Dickens and historic sites questions the definition of the latter in the public mind. Jackson masterfully threads this intricate discussion throughout Dickensland, establishing it as one of the more intriguing facets of his book. Dickens expressed a fondness for the buildings, byways, and structures dating from an older London and he would regularly draw from his memories of this earlier city to partially construct fictional landscapes. Therefore, Dickens’s writing directed literary tourists to sites deemed historic during his own lifetime and to “localities, manners and customs” of an early nineteenth-century London quickly becoming historic themselves.6

A thirst for history characterized Victorian culture, and this desire informed the urban preservation movement in the late nineteenth century. In the decades following Dickens’s death, the process of creating or cataloging sites associated with his biography and writings became formalized and structured to present a tailored and sanitized image of London. For instance, the Royal Society of Arts (RSA) erected the first public plaque in the city commemorating Dickens outside Wood’s Hotel in 1886, sixteen years after his death. Dickens lived as a tenant at this address during the beginning of his writing career in the 1830s when the establishment was known as Furnival’s Inn. The London County Council, a governmental entity deeply involved in both urban heritage and redevelopment, continued the RSA’s plaque program beginning in the early twentieth century with the intent of educating citizens and visitors through interactions with historic and literary sites. This program would eventually mark multiple structures affiliated with Dickens, including his former home in the Bloomsbury neighborhood, which would be transformed into the present-day Charles Dickens Museum.

Additionally, Jackson analyzes the ways that television and film adaptations of Dickens’s novels both reinforce and reinterpret the author’s vision of London and inform readers’ perceptions and interactions with it. He even discusses Dickens World, a short-lived amusement park that attempted to recreate the Victorian London depicted in Dickens works. Dickensland deftly weaves together intricate concepts regarding literature, preservation, and tourism and asks how imagined landscapes might form a brick-and-mortar world.

Much like Charles Dickens, the French novelist Honoré de Balzac and his fiction are wedded to a specific city, in this case, Paris, in the minds of readers. Similar to Dickens, Balzac articulated a deep affinity for the built environment, even describing it as integral to his identity: “There are memories for me at every doorway, thoughts at each lamppost. There is no facade constructed, no building pulled down, whose birth or death I have not spied on. I partake in the immense movement of this world as if its soul was mine.”7 In his slim yet detailed volume, Balzac’s Paris: The City as Human Comedy, Eric Hazan attempts to unpack this lifelong relationship between the author and his city.

Using Balzac’s life and his ninety-odd series of novels and novellas collectively known as The Human Comedy as the basis for Balzac’s Paris, Hazan arranges his own book in thematic chapters focusing on buildings, sites, professions, and phenomena within the French capital. For example, the early segment “A Wanderer” presents a catalog of Balzac’s various residences in Paris and their placement in his biography and writing life. When Balzac was fourteen, his family moved to the city. Later, as a young man and aspiring writer, he rented an attic room in a building near today’s Place de la Bastille. His poor lodgings served as the descriptive source material for the garret of the protagonist Raphaël de Valentin in Balzac’s 1831 novel, Wild Ass’s Skin. A later chapter, “Quarters,” examines how differing Parisian districts define characters in the writer’s fiction and how movements between these districts represent characters’ shifting positions on the social ladder. In the beginning of Old Man Goriot, Eugène de Rastignac arrives in Paris to study law and resides in the Latin Quarter, the preserve of artists, intellectuals, writers, and, of course, students. By the novel’s conclusion, a more hardened Rastignac finds himself established in a fashionable district on the Right Bank by his female lover.

Balzac’s work partially documents a largely disappeared city—an “Old Paris”—and several of his novels are set in this past place. The author often perceived technology as a destructive force afflicting his beloved cityscape. Although railroads were reshaping geography and transportation, his novels do not feature rail stations, and his characters never travel by train. Likewise, Balzac laments the inevitable obsolescence of traditional professions and trades, such as the lamplighter and the paper-monger, amid a fast-changing and modernizing Paris. This nostalgia matches that of literary tourists seeking both the real and imagined London evoked by Charles Dickens.

Balzac’s Paris presents a compelling introduction to the creative interplay between the titular author and the city that stood as his home and artistic wellspring. A selection of maps, prints, and photographs enhances the well-written and brisk narrative. Hazan’s book deserves to be read by scholars and readers of Balzac; however, its depth and coherence weaken at points. For instance, an entire chapter is spent chronicling Balzac’s work as a publisher and critic and his own relationships with printers and publishers. Although interesting from a literary and cultural history standpoint, this portion of Balzac’s Paris presents a tenuous connection to the city as an intellectual or scholarly subject itself. Occasionally, the text reads like a list of Balzac sites alongside quotations from his fiction—a compilation more than an interpretation.

While London fed Charles Dickens’s mind, Paris nourished that of Honoré de Balzac. The spirits of both writers haunt their respective cities, accompanying contemporary readers along their streets. Paired together, Dickensland and Balzac’s Paris chart the fertile exchange between two iconic writers and their respective cities. While Balzac’s Paris presents a close and enjoyable look on how Paris molded a writer and his fiction, Dickensland poses deeper questions—namely, how might an artistic work shape a given place and its history and how might art define our understanding of both long after its creator’s passing?

David J. Goodwin is an author and historian. His most recent book is Midnight Rambles: H. P. Lovecraft in Gotham, a biography of the horror writer’s New York City years.

Featured Image (at top): Frederick James Smyth, London and the River Thames seen from the south, 1845. Wellcome Images, via. Wikimedia Commons.

- Lee Jackson, Dickensland: The Curious History of Dickens’s London (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023), 1. ↩︎

- Jackson, Dickensland, 2. ↩︎

- Jackson, Dickensland, 136.

↩︎ - Jackson, Dickensland, 86. ↩︎

- Jackson, Dickensland, 89.

↩︎ - Jackson, Dickensland, 76. ↩︎

- Quoted in Eric Hazan, Balzac’s Paris: The City as Human Comedy (New York: Verso, 2024), 2. ↩︎