By Dan Holland

The passage of Pittsburgh’s first fair housing law in 1958, the second in the nation, and Pennsylvania’s in 1961 (also among the first statewide fair housing laws in the nation), were rare civil rights victories at a time when record numbers of African Americans were being relocated under the federal urban renewal program. The passage of these laws represented a colossal organizing effort over many years. Joe Trotter and Jared Day write in Race and Renaissance, “the struggle for better housing also included a campaign for new legislation to ensure fair housing in both the private and public sectors.”1

When the law was first proposed in 1957, fair housing had long been a problem for African Americans in Pittsburgh, as it was nationwide. As African Americans moved into the suburbs in small numbers in the 1950s, whites made sure they were not welcome. In 1957, not long after William Levitt constructed his second mass subdivision in Bucks County, outside of Philadelphia (Levittown, New York, was built in 1946), whites used “mob violence” to intimidate a Black family consisting of William Myers, a veteran, and his wife, Daisy. In The Color of Law, Richard Rothstein describes the incident:

As many as 600 white demonstrators assembled in front of the house and pelted the family and its house with rocks. Some rented a unit next door to the Myerses and set up a clubhouse from which the Confederate flag flew and music blared all night. . . . For two months law enforcement stood by as rocks were thrown, crosses were burned, the Ku Klux Klan symbol was painted on the wall of the clubhouse next door, and the home of a family that had supported the Myerses was vandalized.2

Reporting on the violence in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Mel Seidenberg wrote, “Consequently, there is no peace in Levittown today. It is a community under a cloud of unrest, tension, feat, bitterness. State troopers patrol its streets, ready to stop the mob violence which has threatened one innocent family.” He concluded that “Community strife and tension such as that occurring in Levittown would be non-existent if builders or realtors, at the very outset, sold or rented to all persons without regard to race.”3 Incidents like these were par for the course at a Levittown development and many other subdivisions across the country, which, thanks to the Federal Housing Administration, administered “an explicit racial policy that solidified segregation in every one of our metropolitan areas,” writes Rothstein.4

It was within this context that Pittsburgh passed its first fair housing law in 1958, the second in the nation behind New York. It did not come without painful accounts of discrimination. In one case, an African American physician was denied a home loan by a local financial institution. Testifying before a City Council hearing on the city’s proposed fair housing ordinance in 1958, Dr. H. Raymond Primas, an African American physician at Pittsburgh Hospital in Larimer, relayed the story of a friend of his, also an African American doctor, who was denied a home loan just two years prior:

After hearing the description of the desired “dream house” the firm head asked: “where is it?”

Told of the location, he said, “I don’t think we can lend you the money for that.” “Why?” Asked the doctor stunned by the statement.

“We do not want to cause problems,” the firm head replied.

“What kind?” the doctor asked.

“There are no Negroes living in that community,” his friend answered.

Six months later the doctor died, his last days spent brooding about the rejection. His voice quivering with emotion, Dr. Primas gazed into the packed hearing room and sobbed: “I know because that man was my father.”5

There was little opposition to the law, but some spoke out against it, including the Greater Pittsburgh Board of Realtors, on the grounds that it forced property owners to integrate. A Press article noted that, “‘Compulsory housing integration would deprive property owners of a fundamental right,’ Mr. [C. J.] Hoffman [President of the Realtors] said. ‘When government can tell property owners what to do with their property, it can influence a free press, free assemblage, and even free religion.’”6 Pittsburgh’s Commission on Human Relations, established in 1955, was tasked with enforcement. Though restricted to the city limits, Pittsburgh’s fair housing legislation was the first of its kind in the state.7

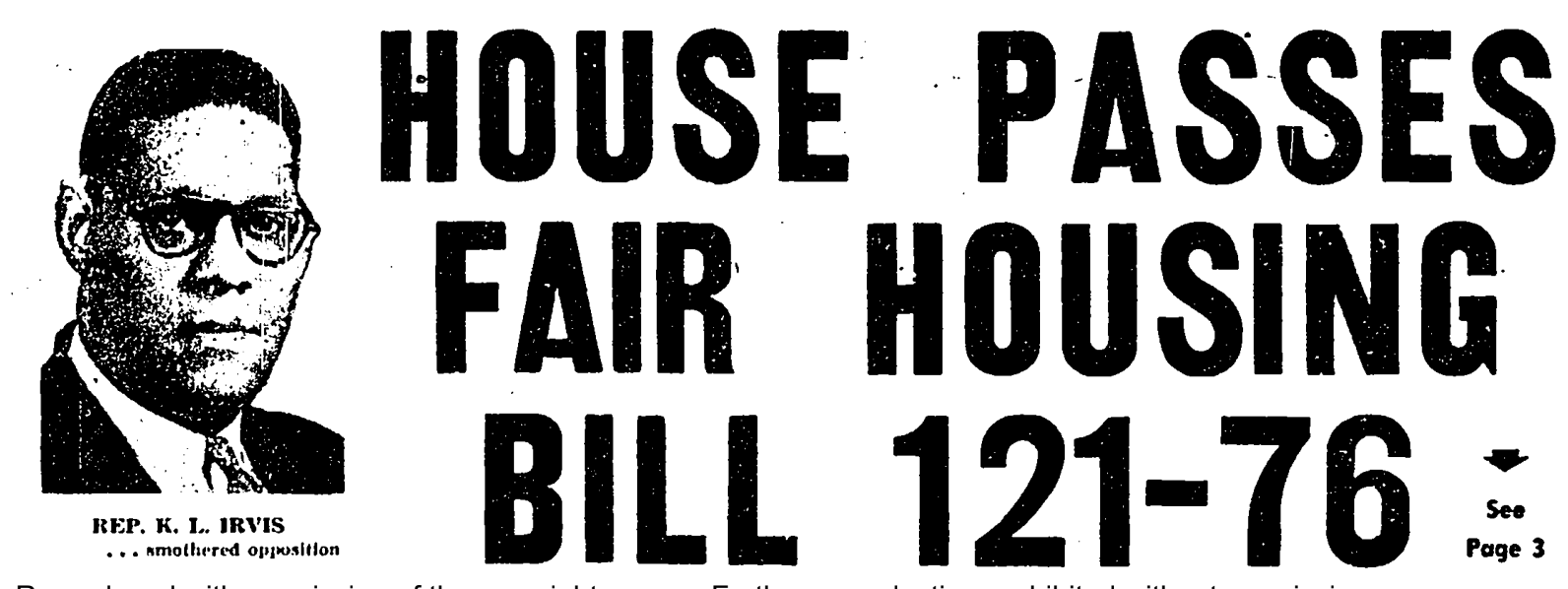

Passage of Pittsburgh’s and Pennsylvania’s fair housing laws were the result of a monumental organizing effort. African American leaders such as Charles C. Holt, chair of the NAACP’s housing committee, Daisy Lampkin, the NAACP’s field secretary, and K. Leroy Irvis, the Hill District’s representative in the Pennsylvania State House, played pivotal roles in the passage of the local and statewide legislation. The law also had help from religious, labor, and social leaders, including Rev. Claude Conley, former pastor of Dormont Presbyterian Church and executive of the Presbyterian Synod of Pennsylvania, Walter Gay, a Philadelphia-based NAACP attorney, and Francis C. Shane, civil rights chairman of the United Steelworkers. Also contributing to the passage of the law was the First Unitarian Church of Pittsburgh, long an advocate of civil rights and social justice.8

As the first Black man to serve as the Pennsylvania Speaker of the House, Irvis used his influence to force passage of the bill in Harrisburg. “In eight efforts to amend the bill, all were defeated under the attack of Representative Irvis, supported by the Democratic House majority, and some help from Republicans,” the Courier reported in February 1961. “Representative Irvis led the floor fight from start to finish for passage of the bill.”9 An Urban Redevelopment Authority internal memo from Mel Seidenberg, while he was still a reporter at the Post-Gazette, noted that “the fight was much closer than vote indicated,” he wrote. “At one point . . . there were 96 no votes; but these switched under administration pressure and following a strong rebuttal by Representative K. Leroy Irvis, Pittsburgh Democrat (himself a Negro), of anti arguments.”10

In addition, Branch Rickey’s star power propelled both the local and state fair housing legislative efforts (along with Mrs. Jonas Salk, whose husband had risen to fame for developing the first polio vaccine). Best known for hiring Jackie Robinson in 1946 during his tenure general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers, Rickey had become the Pirates’ general manager in 1950 until his retirement in 1955. He told the City Council, “‘The potential equality of every human is the same. During the Civil War, 800,000 white men died for the sake of three million colored people, but today the finger of hypocrisy is pointed as us from all over the world—at this very hour—and it says: ‘You have colonialism in your own country.’”11 The city ordinance became law on June 1, 1959.12

In testifying before a General Assembly committee on the statewide legislative proposal in 1959, Rickey said, “‘This is an issue where we have a sense of public duty and where we do not deviate from that duty.’” Mrs. William Myers, who, along with her husband had been the target of white mob attacks in Levittown, Pa., told the State House committee: “‘A law does not make people love you but it certainly guides their actions.’”13 The Pennsylvania Fair Housing Law took effect on September 1, 1961.

Even after the city and state fair housing legislation became law, whites remained defiant at the prospect of new Black neighbors. A Post-Gazette article tells the story of white resistance in Wilkinsburg in 1961. A sign erected on one lawn, “THIS HOUSE NOT FOR SALE,” sent a signal that African Americans were unwelcome no matter what the law says. Fearful whites, pressured by real estate agents, engaged in panic selling, a trend known as “block busting.” “It is based on a fear—a very real fear—that the neighborhood will be ‘inundated’ by Negroes and that, consequently, the value of property there will decline,” wrote Mel Seidenberg in the Post Gazette.14 Though the fears were irrational and unfounded, whites still moved out.

Despite new local and statewide fair housing legislation, little progress was made at the federal level. The U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) made racially restrictive deed covenants unenforceable; yet African Americans remained widely shut out from purchasing homes in certain neighborhoods.15 Not until April 1968 did Congress pass the federal Fair Housing Act, just days after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s death and riots convulsed the nation.

It was the first of many federal laws designed to outlaw racial discrimination in the housing and lending industry. The Community Reinvestment Act, which outlawed redlining, passed in 1977, nearly twenty years after the city’s fair housing ordinance went into effect. And even then, enforcement of the CRA was weak. Not until the late-1980s did the convergence of effective advocacy around the CRA by community activists and strong federal fair housing enforcement cause racist trends to slowly reverse, though not without long-term effects that linger today. Progress, if it does bend toward justice, proceeds ever so slowly.

Dan Holland is the 2025-2026 Post-Doctoral Fellow at the Center for Africanamerican Urban Studies and the Economy (CAUSE) in the History Department at Carnegie Mellon University. He is also an adjunct professor of history at Duquesne University.

Featured Image (at top): View of Downtown from the Hill District, by Clyde Hare, 1950s. Carnegie Museum of Art Collection of Photographs, 1894-1958, 85.4.89, via historicpittsburgh.org.

- Joe W. Trotter and Jared N. Day, Race and Renaissance: African Americans in Pittsburgh Since World War II.

(Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010), 80. ↩︎ - Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New

York: Liveright Publishing, 2017), 141-142. ↩︎ - Mel Seidenberg, “Levittown Racial Trouble Shows Policy Weakness,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 24, 1957.

Melvin Seidenberg Papers, Series IV Articles Regarding Housing Discrimination, Box 2, Folder 14 (MSS 566),

Heinz History Center. ↩︎ - Rothstein, The Color of Law, 70. ↩︎

- “Negro Doctor Tells of Barrier’s Pain. ‘Dream Home’ Lost in ‘No Trouble’ Ruling, Yet Physician Able to Point to

Gains Here,” Pittsburgh Press, November 26, 1958. Melvin Seidenberg Papers, Series IV Articles Regarding

Housing Discrimination, Box 2, Folder 14 (MSS 566), Heinz History Center. ↩︎ - “Integrated Housing Law Urged by Civic Leaders,” Pittsburgh Press, November 26, 1958. Melvin Seidenberg

Papers, Series IV Articles Regarding Housing Discrimination, Box 2, Folder 14 (MSS 566), Heinz History Center. ↩︎ - Weber, Don’t Call Me Boss, 282. ↩︎

- “Religious, Labor, Social Leaders Begin Campaign for State ‘Fair Housing’ Law,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 9,

1957 and “Rights Group Seeks Support From Mayor,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 2, 1958. ProQuest Historical

Newspapers: Pittsburgh Courier. ↩︎ - “Fair Housing Law Wins by 121-76 Vote After Rep. Irvis Smothers Opposition, Pittsburgh Courier, February 25,

ProQuest Historical Newspapers: Pittsburgh Courier. ↩︎ - Mel Seidenberg, Notes on Pennsylvania Fair Housing Practices Law, February 23, 1961. Melvin Seidenberg

Papers, Series IV Articles Regarding Housing Discrimination, Box 2, Folder 14 (MSS 566), Heinz History Center. ↩︎ - “Integrated Housing Law Urged by Civic Leaders,” Pittsburgh Press, November 26, 1958. Melvin Seidenberg 11

Papers, Series IV Articles Regarding Housing Discrimination, Box 2, Folder 14 (MSS 566), Heinz History Center. ↩︎ - Weber, Don’t Call Me Boss, 282. ↩︎

- “Rickey, Sr. Pleads for Housing Bill. Baseball Figure Hits Fear of Negroes by Real Estate Agents,” Pittsburgh

Post-Gazette, May 22, 1959. Melvin Seidenberg Papers, Series IV Articles Regarding Housing Discrimination, Box

2, Folder 14 (MSS 566), Heinz History Center. ↩︎ - Mel Seidenberg, “Signs bare big story in five words,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, March 4, 1961. Melvin Seidenberg

Papers, Series IV Articles Regarding Housing Discrimination, Box 2, Folder 14 (MSS 566), Heinz History Center. ↩︎ - As early as 1917, the Supreme Court ruled that racial zoning ordinances were illegal. ↩︎