This is the second post in Urban and Environmental Dialogues, our January collaboration with the Network in Canadian History and Environment (NiCHE). For other entries in the series, see here.

By Jaida Johnson

I was walking through Chicago with a friend, and we came to a sudden break in the sidewalk. We had to step onto the grass to continue. I didn’t mind the slight detour, but my friend stressed that “the city needs to fix this. It’s not right for us to have to walk on dirt when there’s a sidewalk.” I laughed off her complaint, but then I began to wonder why the presence or absence of pavement generated a strong reaction, especially when we could take five more steps to the next slab without staining our shoes. Yet my friend was upset that we might get dirty, and the very idea of stepping onto dirt rather than the sidewalk carried a stigma for her: something unkempt, out of order. Sidewalks were more than mere concrete paths; they were markers of order, civility, and control over the environment.

Surprisingly, I started thinking about this encounter again after finding a newspaper clipping titled “SWAT Helps Wards Clean Up Their Act.” At first glance, I assumed “SWAT” meant the police tactical unit, but I was wrong. In this case, SWAT stood for “Spontaneous Weed Attack Team,” a Habitat for Humanity and RoundUp-sponsored volunteer group formed in 1993 to remove grass and weeds from sidewalks in Chicago wards.1 Their stated mission, to work towards “safer, cleaner, more livable neighborhoods” caught my attention and left me with more questions. How could weeds between sidewalk slabs threaten the livability or safety of a neighborhood? What does it mean to frame weeds as an enemy and volunteers as a tactical force? Why does the sidewalk appear as a vulnerable frontier needing to be saved from nature?

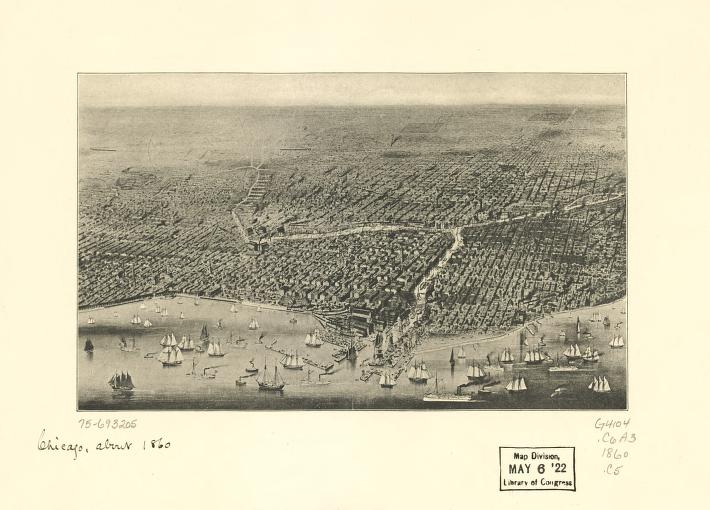

In Chicago, as in many American cities, the sidewalk is not merely infrastructure but a boundary. Sidewalks mark the aesthetic line between nature and civilization. This blog invites readers to see sidewalks as influential in shaping how cities regulate both the environment and human behavior. They are the city’s environmental hinge, mediating between natural forces and social ideals of a civilized order. Through Chicago’s history, specifically during the City Beautiful movement and the civic interventions that followed, sidewalks have revealed how urban reformers sought to “harden” the city against what they perceived as disorder. Eventually, they physically and symbolically separated the civilized from the natural.

In the nineteenth century, Chicago faced a series of challenges brought on by industrialization, rapid population growth, and recurring public health crises. During this moment, the sidewalk transformed into a site where behavioral expectations and environmental standards for a “clean” society were articulated and enforced. As cholera, tuberculosis, and other epidemics spread through the city, scientists and reformers increasingly attributed these outbreaks to overcrowding and poor sanitation.2 A major component of their critique was the overall lack of cleanliness in streets and sidewalks. Their recommendations to utilize urban hygiene as a buffer against disease were quickly taken up by municipal governments.3

This shift is visible in Chicago’s early ordinances. An 1833 regulation imposed a $2 fine on anyone allowing a pig to roam the streets “without a yoke or a ring in its nose”; by 1842, pigs were banned from the streets altogether. These laws drew a clear distinction between the sidewalk as a controlled, civilized space and the unmanaged presence of animals, waste, and other “natural” elements. Over time, urban regulation expanded from animal waste to bodily waste. The rise of germ theory further solidified cleanliness as central to civic identity.4 A clean city signaled modernity, order, and moral uprightness. Ordinances regulating conduct in public, prohibiting spitting, urinating, or leaving refuse on paved surfaces, demonstrate how sanitation became linked to civic virtue.5 Notably, these rules often applied only to sidewalks and other paved areas. Dirt paths, grassy strips, and unpaved streets were subject to far looser regulation, reinforcing a material distinction between the civilized city and the unruly natural world.

While its practical purpose was safety and mobility, the sidewalk also gained significant symbolic weight, revealing how nineteenth-century urban progress depended on taming the natural world beneath people’s feet. This desire for control over dirt surfaced in public demands for cleaner streets. In a letter to the editor published in 1895, an anonymous taxpayer questioned why “wise councilmen” had not enacted “an ordinance which provides that walks shall be kept clean,” noting that multiple complaints had already been made about the deteriorated condition of sidewalks and the streets “being in a dirty condition.”6 By the 1890s, this ideological distinction between nature and civility was amplified by the rise of the City Beautiful movement.7 What had once been a set of hygienic and moral expectations now evolved into a broader aesthetic and ideological program for remaking American cities.

The City Beautiful movement was national in scope, reshaping metropolitan centers across the country, but one of its most influential documents is the 1909 Plan of Chicago. Drafted by architect and urban planner Daniel Burnham, the plan sought to redesign Chicago with principles of order, symmetry, and monumental beauty.8 It aimed to remake both the city’s physical landscape and the social ideals attached to it. With the creation of the Chicago Plan Commission, these visions quickly translated into concrete interventions.9 One of the earliest actions was the widening of Twelfth Street, a project that explicitly included the expansion of its sidewalks.10 This was not simply a matter of traffic flow; it reflected a belief that wide, orderly, and aesthetically controlled sidewalks would promote a more disciplined, refined, and civilized urban public.11

Although the City Beautiful movement eventually receded after World War I, its ideological imprint endured. The belief that sidewalks should embody order, cleanliness, smoothness, continuity, and be visually controlled continued to shape urban expectations long after Burnham’s era. This legacy becomes clear in later conflicts over tree roots and sidewalk maintenance. A 1982 newspaper clipping titled “Residents ‘Threatened’ by Diseased Trees” captures this tension: even though the trees predated the sidewalks, their roots were framed as intruders, as forces that threatened to “damage” a surface imagined as the rightful, orderly baseline.12 The desire for trees coexisted with an insistence that nature remain decorative, never disruptive. When roots buckle concrete, the sidewalk is cast as the victim, another frontier of civility under attack, echoing earlier municipal anxieties about dirt, waste, and disorder.

These small conflicts reveal the persistence of a much older urban logic. Modern cities strive to present themselves as clean, rational, and controlled, yet they remain constantly challenged by natural processes they can never fully contain. Although we never uncovered a definitive answer for why the volunteer SWAT group believed that weeds or patches of grass between sidewalk slabs posed a threat to neighborhood safety, we did find that their concern did not emerge in a vacuum. It draws on a long history of sidewalk cleanliness that frames nature as an adversary to urban order.

Jaida Johnson (she/her) is a Ph.D. student in History at Carnegie Mellon University. She is currently working on a project examining the history of U.S. sidewalks functioning as sites of surveillance for Black pedestrians. Broadly, she is interested in how policing and surveillance technologies are used in urban infrastructure.

Featured Image (at top): VIEW OF BRIDGE FROM WEST SIDEWALK, LOOKING NORTH UP STATE STREET;

NOTE RAILINGS TO LEFT FORMED BY UPPER CHORDS OF TRUSSES – Chicago River

Bascule Bridge, State Street, Spanning Chicago River at State Street, Chicago, Cook County, IL

- “SWAT Helps Wards Clean Up their Act.” Weekend Chicago Defender (1980-2008), May 1, 1993, 12.

↩︎ - Terra Ziporyn, Disease in the Popular American Press: The Case of Diphtheria,

Typhoid Fever, and Syphilis, 1870-1920 (New York: Greenwood, 1988).

John Duffy, The Sanitarians: A History of American Public Health (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1990).

↩︎ - Harold L Platt. “Jane Addams and the Ward Boss Revisited: Class, Politics, and Public Health in Chicago, 1890-1930.” Environmental History 5, no. 2 (2000): 194–222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3985635. ↩︎

- Nancy Tomes. The Gospel of Germs: Men, Women, and the Microbe In American Life. (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press), 1998.

Phyllis Allen Richmond, “American Attitudes Toward the Germ Theory of Disease (1860-1880).” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 9, no. 4 (1954): 428–54. ↩︎ - Abrams, Jeanne E. “”Spitting is dangerous, indecent, and against the law!” Legislating Health Behavior During the American Tuberculosis Crusade.” Journal of the history of medicine and allied sciences vol. 68,3 (2013): 416-50. doi:10.1093/jhmas/jrr073

Patrick J O’Connor, “Spitting Positively Forbidden”: The Anti-Spitting Campaign, 1896-1910. University of Montana Graduate Thesis, 2015. ↩︎ - TAXPAYER. . 1895., Feb 16 “VOICE OF THE PEOPLE.: ADVOCATES SIDEWALK CLEANING.” Chicago Daily Tribune (1872-1922), 14. ↩︎

- Robert Freestone. “City Beautiful Movement.” Encyclopædia Britannica Online 2020. Web; Introduction to Planning History in the United States. First edition. London: Taylor and Francis, 2017. Web. ↩︎

- Daniel Hudson Burnham, and Edward H Bennett. Plan of Chicago. (New York: Da Capo Press), 1970; M.P. McCabe, “Building the Planning Consensus: The Plan of Chicago, Civic Boosterism, and Urban Reform in Chicago, 1893 to 1915,” American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 75:1 (January 2016), 116-148. ↩︎

- James William Pattison, “‘The Chicago Plan’: To Make Chicago Beautiful.” Fine Arts Journal 29, no. 5 (1913): 643–68; Carl S. Smith, The Plan of Chicago : Daniel Burnham and the Remaking of the American City. 1st ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 2006. ↩︎

- Walter D Moody, “‘The Chicago Plan’: To Make Chicago Beautiful, Healthful and Convenient.” Fine Arts Journal 29, no. 3 (1913): 560–74.

Samuel Kling, “Wide Boulevards, Narrow Visions: Burnham’s Street System and the Chicago Plan Commission, 1909–1930.” Journal of Planning History 12.3 (2013): 245–268. Web. ↩︎ - Margaret Garb. “Race, Housing, and Burnham’s Plan: Why is there no Housing in the 1909 Plan of Chicago?” Journal of Planning History 10:2 (2011): 99-113. ↩︎

- Juanita Bratcher. “Residents ‘Threatened’ by Diseased Trees.” Weekend Chicago Defender (1980-2008), November 13, 1982, 6. ↩︎