Guariglia, Matthew. Police and the Empire City: Race and the Origins of Modern Policing. Duke University Press, 2023.

Editor’s note: In the interest of full disclosure, Matthew Guariglia formerly served as an assistant editor at The Metropole. Guariglia oversaw the Disciplining the City series from 2017 to 2023.

By Sarah Frenking

Matthew Guariglia’s Police and the Empire City: Race and the Origins of Modern Policing in New York offers a careful analysis of the evolution of the city’s police from the early nineteenth to the early twentieth century. What separates it from other works on police modernization is its explicit focus on race, ethnicity, and immigration. Guariglia uses the terms “race” and “ethnicity” almost synonymously but points out that ethnicity referred more to those immigrants who were “white” but still deemed a racialized other.[1]

The changing meaning of race itself is thus at the core of this insightful book. The author not only focuses on how people were policed according to race and the police’s relationship with the multiracial population of New York City, but also how immigrant police officers were rewarded with social mobility within the ranks of the police, how they became “Americanized” and could thus consolidate their (precarious) whiteness. To its credit, the book traces the career trajectories of multiple non-white policemen and their role in shaping law enforcement but also highlights the role of white law enforcement leaders and their visions about race and policing in the light of modernization efforts. This is why Guariglia understands the New York Police Department as an “engine of racial management”.[2]

The book is organized chronologically over eight chapters spanning from the origins of the New York City Police Department in the 1840s to the Interwar Period. The first chapter lays out the creation of the NYPD in 1845, which replaced the former night watch system and was based on London’s Metropolitan Police. It is mainly concerned with Irish immigrants, who were stigmatized as violent rioters and unreliable citizens. Despite the dominance of anti-Irish and anti-Catholic sentiment and being treated as racially dissimilar to Anglo-New Yorkers, the first immigrant police officials experienced social mobility through civic engagement. For many Irish New Yorkers, policing even became a family business, spanning two or more generations. However, their consolidation of whiteness, as Guariglia argues, relied on enforcing anti-Black policies such as the capturing of enslaved people and anti-Chinese policing.

Through the lens of race, the author also offers another explanation for the short existence of two New York police agencies in 1857, the municipal and the metropolitan police, that he not only explains through the tensions between local and state-legislature police (which was also common in Europe), but also through an ethnic division between immigrants in the ranks of the former and policemen of Anglo-Dutch heritage in the latter.

The second chapter deals with bodies, morality, and gender at the end of the nineteenth century. Guariglia explains how police understood vice districts and places where sex work took place as equivalent to neighborhoods predominated by racial and ethnic minorities. Hence, policing sexuality and ensuring the moral purity of white women, especially in proximity to Chinese opium dens, led to the penalization of working-class women as well as the criminalization of non-white men. Guariglia also sheds light on undercover practices of investigating suspicious establishments such as brothels and gambling halls and how such practices offered opportunities for personal enrichment. By the end of the nineteenth century, moral crusaders were very concerned with corruption, leading to the establishment of the Lexow Committee to research police extortion, bribes and brutality. Additionally, because of the disproportionate employment of Irish police, corruption became synonymous with Irishness. As part of police professionalization at that time Police Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt, who shortly after became President of the United States, claimed the necessity of alleged toughness and new ideals of “manliness” that policemen should embody, which he considered Jews in particular to be incapable of.

The third chapter explores the journey of General Francis Vinton Greene, who brought practices from the imperial project in the Philippines and in Cuba back to New York City, where he became commissioner in 1903. The chapter explores how these colonial methods were relevant for the militarization of police and the creation of a centralized police system, but most importantly the establishment of ethnic squads that were supposed to control and mediate in their “own” communities. Guariglia argues that because the city welcomed more and more immigrants at the turn of the century, the NYPD now included “natives” in the maintenance of order to pacify a population and overcome language barriers. Following this, Chapter Four further examines the rise of ethnic policing by the end of the nineteenth century. Based on the fear that criminals “could lean into their foreignness in order to avoid detection and arrest”[3] and thus the need for police translators, the “German squad” was created in 1904. Its 100 policemen were supposed to deal with the influx of German and Yiddish speakers; the main offenses that police sought to fight among these new immigrants settling in downtown Manhattan were sexual crimes, especially “white slavery,” the abduction of white women for purposes of prostitution, and drugs. Here in the eyes of the NYPD especially the role of Jewish men was of interest and the growing Jewish neighborhood had to be infiltrated. In addition, a policeman of Chinese descent was employed in Brooklyn, and these “ethnic” policemen slowly made the transition from translator to patrolmen and detective.

Ethnic squads are further analyzed in the fifth chapter, in which Guariglia expands on the link between deportation laws and local crime through the “Italian problem.” He analyses the creation of an Italian Squad after the turn of the century and how early criminology from Europe played a role in depicting Italians, especially those from Sicily, as an inferior race. Italians were also demonized, often conflated with radical anarchism as well as transatlantic organized crime. Guariglia draws on the US press’ “invention” of the Black Hand, which was in fact not a mere invention but rather a media exaggeration of the practice of extortion.

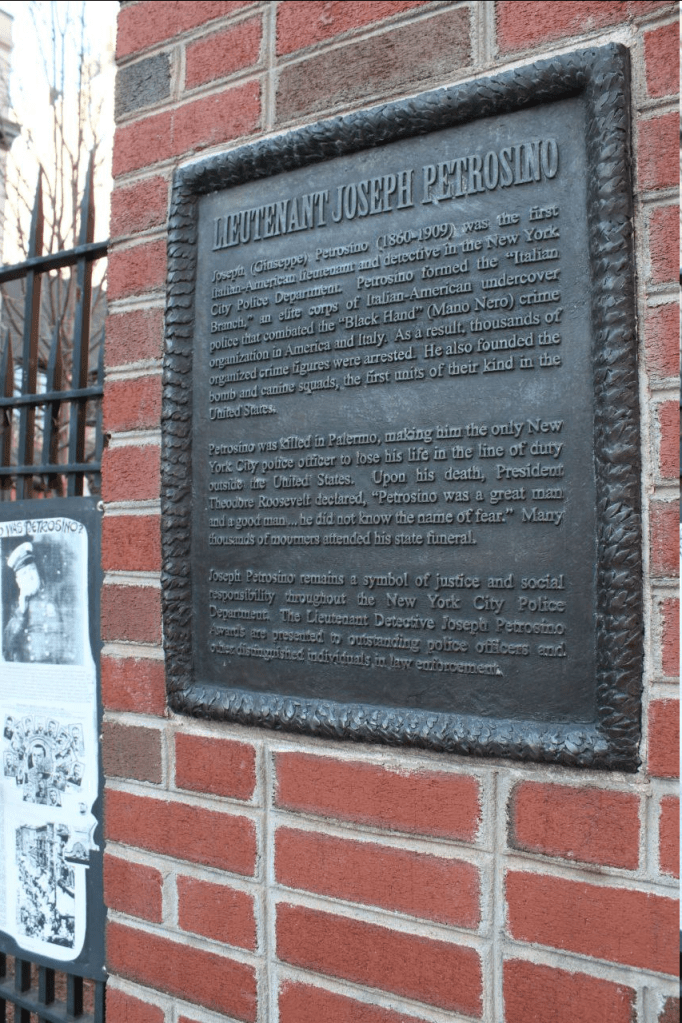

After downgrading the Italian Squad in 1908, police commissioner Theodore Bingham instead made deportations the primary method to curb so-called immigrant crime in New York City. This chapter shows how federal legislation like the 1903 Immigration Act established criminal convictions abroad as basis for deportation from the United States, subsequently increasing the role of deportations as a policing measure in local law enforcement. Similarly, the Mann Act of 1910, a federal law established to fight “white slavery,” enabled the local policing of interracial couples. Guariglia argues that the example of the first Italian-born police officer, Joseph Petrosino, shows that Italians “could be made less different” compared to African Americans or Asian immigrants, because in the eyes of the NYPD they were capable of respectability through civic participation.

In comparison to other non-white groups, “Black New Yorkers did not seem to constitute a ‘police problem’ worthy of the intellectual labor dedicated to policing illegible immigrants”.[4] Therefore, Chapter Six explores racial criminalization of African American New Yorkers. Guariglia points out that the category “Black” disappeared from police records after 1905, which he argues serves as an attempt to erase a history of police brutality. Yet, arrests in Black neighborhoods were disproportionally high and the relationship between police and Black communities was tense. This can especially be seen in the 1900 case of a Black man stabbing an undercover policeman who had molested a Black woman, which led to violent outbursts and a white mob attacking African Americans.

The hiring of Black officers in the NYPD stemmed from differing motivations. Despite the growth of New York’s Black population at the turn of the century, reformers did not advocate for Black police, since in contrast to immigrant groups, Black New Yorkers spoke English. Instead, calls for police reform and discussions around police accountability after the anti-Black violent outbursts led to the introduction of African American policemen, one of the first being Samuel Battle, appointed to the NYPD in 1911.

If in his first six chapters, Guariglia explores the significance of race and ethnicity in policing New York City, in his final two chapters his analysis occasionally loses sight of this argument and focuses more on general developments regarding the role of bodies for policing.

Guariglia’s seventh chapter explores the influence of World War I on police modernization and links it to the beginnings of police science, such as criminology and identification techniques. It underlines the importance of police handbooks, increased training, and police libraries, as well as the influence of organizations such as the Bureau of Social Hygiene as one of the largest producers of knowledge about policing and criminality in the US. On behalf of the Bureau, public administrator Raymond Fosdick traveled to Europe between 1913 and 1917 and brought back new techniques to identify suspects such as Bertillonage, a system that used body characteristics to identify recidivists, and fingerprinting, which made the NYPD one of the earliest US departments to implement these practices. Through this development, the author argues, a new standardization of bodies took place. Convincingly, and similar to other chapters, this chapter includes those policing and those being policed. World War I led to an emphasis on “preparedness” within the NYPD, including the ideal of masculine and fit bodies of policemen, one that even encompassed preferred modes of chewing and eating.

The last chapter links the adaption of European policing measures to what the Guariglia calls “color-blind” policing. The reader could benefit from Guariglia’s specific definition of the term, as he uses it to refer to making subjects equally identifiable through the aforementioned techniques. The author argues that these technologies aimed to register suspects and recidivists as a way to enable the NYPD to “read” bodies of immigrant residents and make them understandable – a quite narrow interpretation as I will explain below – and later spread to other parts of the US. Guariglia then quickly introduces the influence of eugenics in criminological discourse of the 1920s, ideas of “born criminals,” and the concept of a particular race’s predilection for criminality. Linking this discourse to antisemitism, especially given the discourse on transnational crime that flourished internationally and in the US during the 1920s, when trans-continental networks and secret relationships were linked to “international Jewry,” would be promising for future perspectives on the history of how policing was based on racism and prejudice.[5]

The book concludes with critical remarks on how the NYPD presents and remembers its history today. Since 1987 and 2009, respectively, a “Petrosino Square” and a “Samuel Battle Plaza” have existed, acts of commemoration which Guariglia convincingly criticizes as an “attempt on the part of the NYPD to inscribe an imagined century of good police-community relations onto the visible landscape of the city”[6] and to promote the message that not civilians, but immigrant and Black police officers, were the real victims of prejudice in New York’s society.

Due to its own destruction of files, many of the sources from the NYPD administration do not exist anymore. Out of necessity Guariglia finds creative workarounds, as he draws on police writings, correspondence, court material and an impressive amount of newspaper articles. The personal papers of commissioners, departmental reports, training manuals, police publications, and memoirs from detectives serve as much of the book’s source material, through which he successfully manages to compile a very dedicated exploration of the subject that is committed to “show the work of racial state violence”.[7]

While a study well worth reading, some points could have been argued more carefully. The lack of a clearer localization of the book in the state of research makes it difficult to grasp the merit of Guariglia’s research in the fields of police history, migration history, and global history. While the book is a valuable contribution to the history of policing the urban space, and the growing literature on migrants, ethnicity, crime and criminal justice, Guariglia does not fully succeed in demonstrating in which way the “imperial feedback” from policing in the Philippines and transatlantic transfers of knowledge contributed to the existence of a “global collaborative system of racial state violence.”[8] Here and at other points the language is sometimes very polemical; when the author refers to police as a “machine,” the product of which is “the brutalization and subordination of working-class people and racial minorities, the protection of profits, and the enforcement of gender roles and sexual relations”[9] the wording is detrimental to the book itself, given the fact that its most important point is that policing is a practice and an experience of being policed, both remarkably influenced by racism, and not a simple impersonal system. Modern policing should rather be “understood as the product of interaction between an idea, its transmission through particular agents and institutions, and the local social and political context in which it has been applied.”[10] And this is exactly what Guariglia shows: the importance of police reformers and single agents, of practices and ideas in establishing a system of policing along the lines of race and ethnicity.

Though well written and accessible to a popular audience, additional guidance for readers would have made it easier to distinguish between the main focus of each chapter. Topics such as the moral panic of “white slavery,” the riot against African American New Yorkers in 1900, the importance of deportation policies, the introduction of identification methods, or the role of the Bureau of Social Hygiene appear in several chapters, which leaves the impression that the author is jumping back and forth. It might have been helpful to link the chapters more clearly to the different waves of immigration, thus contextualizing policing more within contemporary anxieties about specific groups.

This would also have highlighted their efforts to try to find a place in society. Crime is more than discursive attribution and police labelling. For historians of crime and police, tracing different people’s ways of making a living or advancing their social mobility through means that collided with the law sheds light on their economic circumstances. For this reason, policing in this period is often not only about race, but intersects with class. This can clearly be seen in the evolution of identification techniques, which, as mentioned above, the author associates solely with the policing of immigrants. The European practice of using papers, descriptions and fingerprints to register Romani people shows, however, the complicated intersection of class and race, since they were targeted both as a racialized group and as a perceived poor “underclass”.[11] In general, identification measures not only targeted “immigrant bodies”, as the author argues, but were at the same time a tool of the newly emerging criminal police, a tool to verify the increasingly significant national identity, and a tool to target the (vagrant) poor.[12]

In sum, Guariglia’s book is an important contribution to the history of policing, setting a standard about how to highlight the crucial role of race and ethnicity for future research. We do not only learn how the police changed and what the modernization of techniques, personnel, organization encompassed – a story that has often been told – but we learn how that was intertwined with the changing meaning of race and ethnicity, from the experiences of and discourses about Irish, Italian, German, Jewish, Chinese, and Black New Yorkers.

Sarah Frenking is an Assistant Professor of Modern European History at the University of Geneva. Her research focuses on the history of crime and policing, gender history and the history of sexuality and prostitution, mobility, migration and border studies, as well as transnational history of the 19th and 20th centuries. Her current research project deals with “Traffic in Women”and Sex Work Mobility between State Prostitution, Transnational Criminality and Female Agency (1920s–50s). Sarah obtained her PhD from the University of Göttingen in 2020. Her first monograph Zwischenfälle im Reichsland. Überschreiten, Polizieren, Nationalisieren der deutsch-französischen Grenze, 1887-1914 (Incidents in the Reichsland. Crossing, Policing and Nationalizing the Franco-German Border, 1887-1914) was published with Campus in 2021.

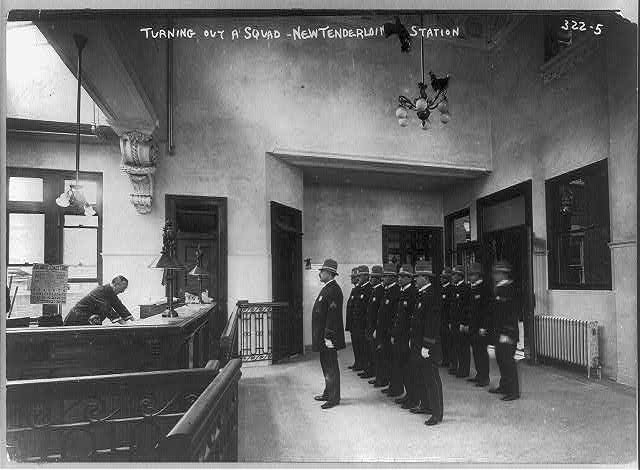

Featured image (at top): Turning out a squad; Police at attention before the desk, New Tenderloin Station, August 1908, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

[1] Guariglia, Matthew. Police and the Empire City: Race and the Origins of Modern Policing in New York. Durham, London: Duke University Press, 2023, 11.

[2] Guariglia. Police and the Empire City, 4.

[3] Guariglia. Police and the Empire City, 101.

[4] Guariglia. Police and the Empire City, 139.

[5] Knepper, Paul. International Crime in the 20th Century: The League of Nations Era, 1919-1939. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011.

[6] Guariglia. Police and the Empire City, 200.

[7] Guariglia. Police and the Empire City, 23.

[8] Guariglia. Police and the Empire City, 17.

[9] Guariglia. Police and the Empire City, 22.

[10] Finnane, Mark. “The Origins of ‘Modern’ Policing.” in: Knepper, Paul and Anja Johansen (Eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Crime and Criminal Justice. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019, 467.

[11] About, Ilsen. “Underclass Gypsies: An Historical Approach on Categorisation and Exclusion in France in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries.” in: Stewart, Michael (Ed.). The Gypsy “Menace”. Populism and the New Anti-Gypsy Politics. London: Oxford University Press, 2012, 98.

[12] Koster, Margo de, and Herbert Reinke. “Migration as Crime, Migration and Crime.” Crime, Histoire & Sociétés / Crime, History & Societies 21, no. 2 (2017): 63–76.