This post is an entry in our ninth annual Graduate Student Blogging Contest. This year’s theme is “Light.”

By Charlotte Leib

“Surely you’ve heard about the penguins,” behavioral ecologist Joanna Burger remarks.

I am speaking with Burger, a Distinguished Professor of Biology at Rutgers, because I’ve reached an impasse—the historian’s equivalent of night. I’ve been attempting to discern how the first systems for the production of kerosene and electric light in the United States affected avian life in my dissertation’s primary research site, the New Jersey Meadowlands—an urban estuary as notorious for its pollution levels as it is famous for its migratory waterbird and raptor colonies.

My research has yielded certain leads. I know, for example, that Thomas Edison established the world’s first industrially scaled electric lamp works, the West Newark Lamp Works, on the Meadowlands’ marshy plains in 1881, and that the Standard Oil Company installed the world’s first long-distance crude oil pipeline across the Meadowlands in the same year, for the production of kerosene.[1] I have evidence, too, that that pipeline persistently leaked.[2] But I have yet to find historical accounts connecting the observed decline of bird species in the 1880s through 1920s in the Meadowlands to the novel influx of electric light and crude oil into the estuary.[3]

So I call up Burger for guidance.

Ecologists and toxicologists like Burger can now confirm, through their research, that the influx of electric light and spilled oil into estuaries like the Meadowlands in the late-nineteenth century, along with the growth of modern lighting systems, would have harmed local wildlife, especially birds. In fact, they use a special term to refer to the conditions that birds and other animals faced amidst urban industrial affronts to their habitat. They call these conditions “no-analog situations.” The term essentially means an ecological scenario with no historical precedent; one to which a given animal has yet to evolve or adapt.[4]

On our call, Burger and I discuss the effects that the “no-analog situations” created by the first electric streetlamps and pipeline oil spills would have had on the Meadowlands’ avian life in the nineteenth century. She tells me about how the novel pulse of electric light through the landscape would have disrupted birds’ behaviors and navigation, and about how coincident oil spills would have damaged their feathers and habitats, while inhibiting their ability to successfully reproduce.[5]

Burger is an expert on these topics, and particularly on how oil pollution affects birds. At eighty-four, she has spent decades studying the effects of contemporary oil spills and chemical pollution on avian life in waterways near the Meadowlands.[6] But as we speak, our conversation takes an unexpected turn.

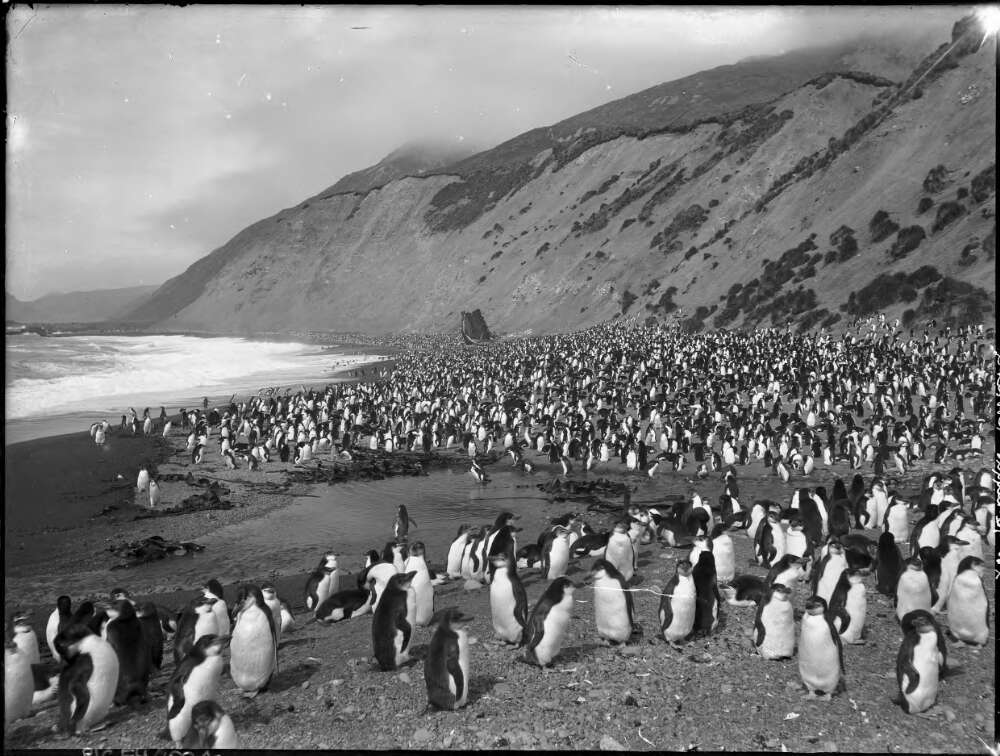

Burger tells me about how, beginning in 1890 on Macquarie Island in the South Pacific, New Zealand entrepreneur Joseph Hatch erected giant steam-heated vats to boil down penguins for oil, for light. The penguins, being curious creatures, simply walked up planks leading to the vats, peered down, and fell in. In other instances, workers killed Macquarie penguins by clubbing them to death. What unfolded was slaughter on an almost unimaginable scale: the massacre of some three million penguins on Macquarie at the turn of the twentieth century—all to bolster Hatch’s bottom line; all in the name of light.[7]

What to make of these penguins? The story of their grim slaughter would seem an unlikely place to begin an essay about light in urban history. Certainly, the penguins’ portraits—remote and rural—belie any hint of the urban.

Yet these penguins’ final destinations were towns and cities. Once transformed into oil by steam-powered digesters, the boiled-down penguins were shipped in barrels to urban ports in New Zealand, Australia, and Great Britain. From there, their oils were used to grease saddles, lubricate machines, and turn night into day.[8]

Penguins don’t often show up in the narratives we write as urban historians—and that may be fine, given the uniqueness of the Macquarie Island example. But the obscure and largely forgotten story of the Macquarie penguins’ plight, along with the lack of published scholarship on topics as significant as how the first systems for the production of kerosene and electrical light affected birds in urban estuaries, like the Meadowlands, together speak to a notable gap in urban history scholarship.

Urban historians have written much about technological and social change in cities and very little about the ways in which historical transformations in lighting technologies have affected environments and ecologies, and the habitats and health of birds.

Jeremy Zallen’s masterful American Lucifers: The Dark History of Artificial Light, 1750–1865 (University of North Carolina Press, 2019) offers one salient example of how the production of artificial light can be critically studied as a formative, far-reaching, and even violent social and material force.[9] Yet there remains much more work to be done to decipher and expose how the workscapes and necroscapes borne from the production of artificial light affected people, animals, cities, and environments together, in tandem. That historiographical gap is one I aim to address in my dissertation on the New Jersey Meadowlands, and it also underpins this essay’s key conceptual provocation.

As birds and other living beings continue to suffer and die by the billions each year due to the chemical and spectral footprint of our brightly lit world—not just from the glare of electric lights, but from legacy mercury poisoning from coal emissions and the historic production of fluorescent lights, and the continued waterborne pollution caused by the spillage of oil-based dielectric fluid used in power lines—we should ask: In our teaching, writing, and research, in our conversations and actions, how can we begin to heal the wounds inflicted upon birds and other creatures by the production and spread of artificial light?

In the remainder of this essay, I outline several ways we can begin to move beyond historical celebrations of urban lighting systems’ brilliance to recognize and mediate the extent of these systems’ historical and ongoing brutalities.

While it might, at times, seem difficult to substantively intervene in the complex, and often violent, material systems we study, our work as historians can shape how these systems are understood, valued, and ultimately changed. And so, too, can the everyday actions each of us—historians or not. Embracing the spirit of optimism and action instead of resignation and despair—and remembering, too, that the penguin rookeries of Macquarie were ultimately saved thanks to enterprising human initiative and new conservation policies—I share below three ways in which we can begin to heal the proverbial wounds inflicted upon human and non-human beings by artificial light.

1. Writing and teaching histories of light and darkness from a bird’s-eye perspective

In the landscape I write about in my dissertation, the New Jersey Meadowlands, birds and other animals lived in a darkness disturbed in eighteenth-century America only by the occasional candle lantern, rushlight or oil lamp—in what scientists now call “true night.”[10] So dark was the night that travelers passing through the Meadowlands sensed that they had reached the town of Newark not by looking for light, but by listening for the sound of croaking frogs.[11] As late as 1830 in nearby Manhattan, a night watchman collided blindly with a pole after running to respond to the sound of a disturbance in the dark.[12]

Today, birds in cities worldwide collide with buildings for the opposite reason. They suffer from the proliferation of glassy structures and from our excessive use of artificial light.

“In just the past forty years, due to the sheer amount of new glass construction on Manhattan,” says landscape architect and bird-safe design advocate Kate Orff, “we’ve turned the city into a giant bird killer. Along the very flyways that birds depend upon, we’ve transformed an island which was legible as this dark, rocky outcropping—with masonry buildings that were an extension of the geology of that outcropping—into a glass death trap that needlessly kills birds.”[13]

As Orff’s observation attests, the lighting environments that birds experience in cities like Manhattan have shifted dramatically in just a few human generations. Too few urban histories currently address these transformations. From the soundscape and lightscape of pre-industrial Newark, to the ecological effects of the first-ever electrically-lit buildings in cities, to today’s glassy skylines: opportunities abound to write histories of urban environments, quite literally, from bird’s-eye perspective. We should lean into those opportunities.

2. Addressing the fast, slow and forgotten violence of artificial light

Writing and teaching histories from a bird’s-eye perspective comes with a second benefit. It prompts us to contend with artificial light as a form of fast, slow, and forgotten violence—not just upon birds and other animals, but upon humans, too.

Since the 1980s, scientists have assembled a spate of evidence concerning artificial light’s epidemiological effects on humans. Between the discovery that night-workers and urbanites exposed to constant artificial light have higher rates of breast cancer and other diseases to the death toll caused by the disorientation drivers experience when they encounter glare from oncoming headlights, artificial light has affected and continues to affect humans and other animals in fast, slow, and forgotten ways: from the sudden accident, like a bird strike or car crash, to the presence of legacy pollutants in environments and bodies (like mercury, in birds), to the creep of light-related chronic diseases.[14]

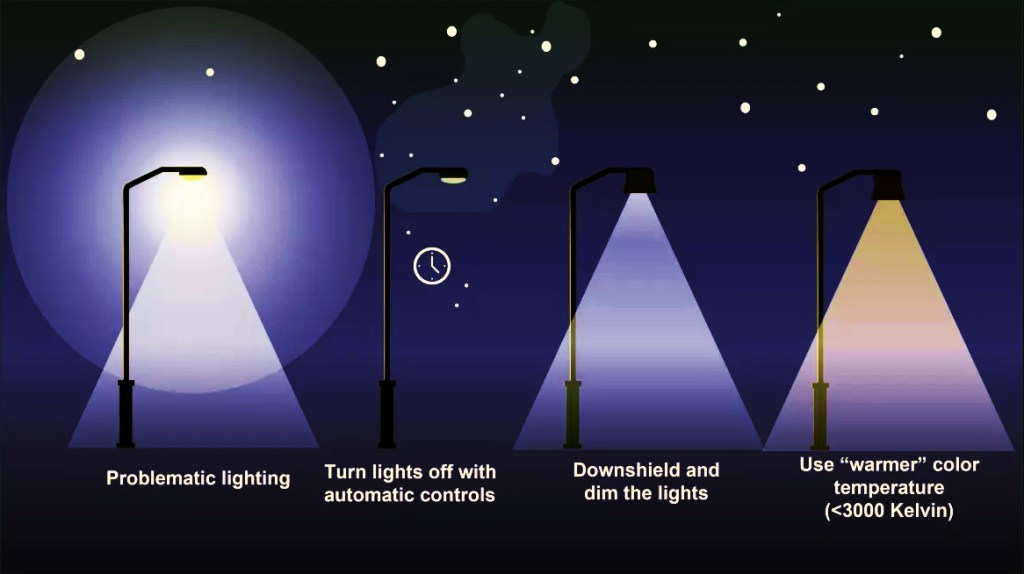

Bird-conscious glass and shielded, dimmed streetlights can help reduce bird mortality rates and improve human health. But if we overlook the suffering and violence caused by artificial light in urban environments today and in the past, we’ll never escape it. We should follow the lead of scholars like Rob Nixon, who introduced the term slow violence into environmental humanists’ and activists’ lexicon in his 2011 book Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor, and commit to writing and teaching about the hidden and cumulative harms of artificial light, while advocating for healthy lighting practices.[15]

3. On climate change, biodiversity loss, corporate control, and turning out the lights

Finally, we can simply turn out the lights.

After historic events like the 1965 Northeastern blackout and during the 1970s energy crisis in the US, turning out lights became a political and environmental act: a means of conserving energy and doing one’s part to lessen demands on the electrical grid. In 1790s revolutionary France, disgruntled Parisians smashed the city’s newly installed oil lamps to protest the excesses of the ancien régime, and all that light then symbolized.[16]

Historical moments like these reveal how mobilizing around the use of artificial light can be a powerful means of change and protest. At a time when corporations continue to dictate the terms of climate and environmental policy agendas worldwide, as biodiversity loss continues unchecked, and as billions of birds continue to be injured and killed by our overly-lit skylines each year, the spread of artificial light remains one thing we—as individuals and communities—can work to control.[17]

“Light pollution, unlike climate change, is imminently solvable,” notes scientist Neil Carter, principal of the University of Michigan’s Conservation and Coexistence Research Group. “There’s so much research now that shows light pollution’s negative effects on both humans and animals. We’ve got technologies to limit bright light, stray light and blue light, for example. There are many things we can do.”[18]

One solution is installing lights that have warmer wavelengths, which are better for both humans and birds. Another is simply choosing—when the moon rises—to turn out the lights.

Charlotte Leib is a Ph.D. Candidate in History at Yale University. Trained in US and early American environmental history, energy history, landscape history, and urban history, she is a historian and educator with fourteen years of combined experience in the fields of history, landscape architecture, design, and education. Her research for this piece was supported in part by a 2025-26 grant from the Yale Law, Environment & Animals Program.

Featured Image (at top): Illustration by the author.

[1] Edward J. Lenik, “The Olean-Bayonne Pipeline,” IA. The Journal of the Society for Industrial Ecology 2, no. 1 (1976): 29–34; “The Rich History of Harrison Plaza Mall,” Your Harrison.com, May 18, 2022, https://www.yourharrison.com/blog/the-rich-history-of-harrison-plaza-mal. Accessed July 23, 2025; “Harrison / West Newark Lamp Works,” Lamptech, August 20, 2017, https://www.lamptech.co.uk/Documents/Factory%20-%20US%20-%20Harrison.htm. Accessed July 23, 2025.

[2] On the frequency of leaks and bursts in nineteenth-century oil pipeline systems, see Christopher Jones, Routes of Power: Energy and Modern America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 143, fn. 50. The first recorded leak of the Olean pipeline described here in the Meadowlands recorded in January 1882. Another leak of the pipeline in northern New York resulted in three days of fire near Unionville, NY from March 10–13, 1886. See “Bonfires of Crude Petroleum: Heavy Loss of Oil Caused by Breakages in a Pipe Line,” New York Times, March 14, 1886, p. 1, col. 4, https://nyti.ms/4iEj2I2. On the prevalence of pipeline leaks in the nineteenth century near Newark Bay and New York Harbor, see Andrew Hurley, “Creating Ecological Wastelands: Oil Pollution in New York City, 1870–1900,” Journal of Urban History 20, no. 3 (1994): 340–394 (354, fn. 47).

[3] On the observed decline of birds in the Meadowlands in the late-nineteenth century, see for example: Frank M. Chapman, Bird Studies with a Camera (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1900), 89, https://www.google.com/books/edition/Bird_Studies_with_a_Camera/bYU6AAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA89&printsec=frontcover.

[4] Interview with Neil Carter, 31 July 2025. See also, Carter’s co-authored publications on these topics: Masayuki Senzaki, Jesse R. Barber, Jennifer N. Phillips, Neil Carter et al., “Sensory pollutants alter bird phenology and fitness across a continent,” Nature 587 (2020), 605–609 (2020), doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2903-7; Ashely Wilson, Neil Carter et al., “Artificial night light and anthropogenic noise interact to influence bird abundance over a continental scale,” Global Change Biology 27 no. 17 (2021): 3987-4004, doi:10.1111/gcb.15663.

[5] Interview with Joanna Burger, 24 July 2025. For additional ways in which electric lights affect birds’ behavior and health, see for example: Irene Fedun, “Fatal Light Attraction,” Journal of Wildlife Rehabilitation 18, no. 3 (Fall 1995): 10–11, https://theiwrc.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/07/Volume-18-No.-3-Fall-1995.pdf. Accessed 26 July 2025; Sidney A. Gauthreaux and Carroll G. Belser, “Effects of Artificial Night Lighting on Migrating Birds,” in Ecological Consequences of Artificial Night Lighting, edited by Catherine Rich and Travis Longcore (Washington, Covelo, and London: Island Press, 2006).

[6] See Burger’s two key books on these topics: Joanna Burger, ed., Before and After an Oil Spill: The Arthur Kill (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1994) and Joanna Burger, Oil Spills (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1997), and her many peer-reviewed articles.

[7] Interview with Joanna Burger, 24 July 2025; Geoffrey Chapple, “Harvest of Souls,” New Zealand Geographic (Jul–Aug 2005), https://www.nzgeo.com/stories/harvest-of-souls/. Accessed 27 July 2025.

[8] “Penguin Oil Trade,” Evening Star (Dunedin, NZ), 3 June 1905; “Penguin Oil for London,” Otago Daily Times, 12 June 1905; Chapple, “Harvest of Souls.”

[9] Zallen does an excellent job of showing how shifts in Americans’ forms of artificial lighting technologies together affected cities and landscapes, and occasionally animals. For example, during the 1840s through 1860s, a surfeit of hogs in the American Midwest led Cincinnati, Ohio to become a primary producer of not just pork products, but also candles made from their fat. American lighting systems thus changed in response to conditions of surplus as much as humans’ actual resource needs. See Zallen, Chapter 4, “Lard, Lights, and the Pigpen Archipelago,” American Lucifers, 136–167.

[10] On scientists’ use and definition of the term “true night” see: Fabio Falchi, Pierantonia Cinzano, Christopher C. M. Kyba et al., “The new world atlas of artificial night sky brightness,” Science Advances 2 (2016), 6e160037, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4928945/.

[11] Frogs continued to croak and thrive in the Meadowlands until the onslaught of industrial pollution and oil spills became more prevalent in the 1870s and 1880s. See: “The Salt Meadows,” Newark Daily Advertiser, Tuesday Evening, February 2, 1869. I discuss the pre-industrial soundscape of the Meadowlands further in my dissertation.

[12] Peter Baldwin, In the Watches of the Night: Life in the Nocturnal City, 1820–1930 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 10, fn. 20.

[13] Interview with Kate Orff, 31 July 2025.

[14] For a good summary of some of the early epidemiological research that revealed connections between overexposure to artificial light to the prevalence of various health ailments, including breast cancer, see: Paul Bogard, The End of Night: Searching for Natural Darkness in an Age of Artificial Light (New York, Boston and London: Little, Brown and Company, 2013), 93–124.

[15] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011).

[16] Bogard, The End of Night, 56. See also: Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Disenchanted Night: The Industrialization of Light in the Nineteenth Century (Berkeley, University of California Press, 1995).

[17] The Acopian Center for Ornithology also recently published a revised estimate that building collisions kill up to 3.5 billion birds in the US yearly. This is much greater than the previous estimate of up to 1 billion birds yearly. See “Birds and Windows,” Acopian Center for Ornithology, Muhlenberg College, https://www.muhlenberg.edu/birds-and-windows/. Accessed 29 July 2025.

[18] Interview with Neil Carter, 31 July 2025.