By Genevieve Carpio

Being a historian often means living with the contradictions of the present. As an Angeleno, I see my city in pain. There is resilience and courage too, but the suffering caused by the recent immigration raids is suffocating. As a professor of Chicana/o and Central American Studies, and as a Latina going about her everyday life, I feel the emptiness of places once full of immigrants and their families. A terrifying calculus plays out each day as the most vulnerable navigate which risks are worth taking when entering public space, where the cost of moving through the city could be deportation. Sidewalks, parking lots, bus stops, and worksites have all become places of vulnerability. Among those interfaces most feared is the road.[1]

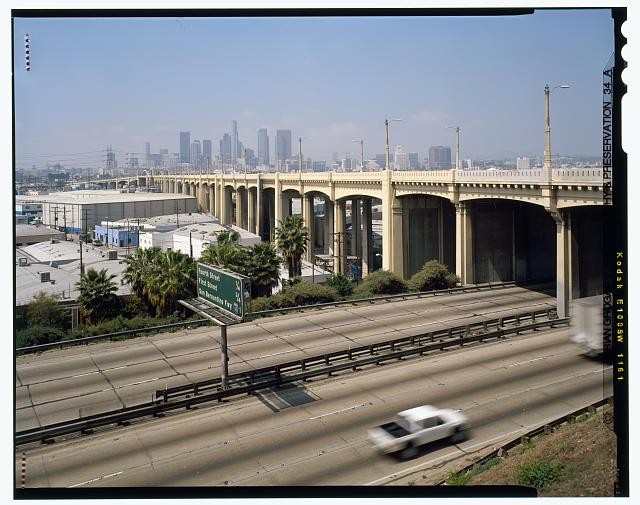

The road has long been tumultuous for Latinos in places like California, as a site where the private space of the automobile and the public space of the street meet. And Californians have long understood the dangers of this interface, leading to visual commentary by artists like Carlos Almaraz, street interventions by organizations like CicLAvia which draw inspiration from Latin America to reenvision roads without cars, and political reform around access to drivers’ licenses for undocumented drivers.[2] But beneath the road lies an invisible infrastructure that demands greater attention: insurance.

As business and economic historians would argue, insurance, a multi-trillion-dollar global industry, shapes our lives in profound ways. Even where the intricacies of these systems may escape many of us, the anxieties they produce are a daily reality for vulnerable populations. As urban historians prepare to gather a the UHA conference in Los Angeles for the first time, I want to interject a distinctly urbanist lens to that conversation, one pointed at the automobile. And I want to show that a focus on California cities demands our eyes have a periscopic vision reaching back to the 1920s, through the post World War era, and into the present. We’ll first start with an economic argument. But my ultimate destination lies in the ways the financial stakes intersect and amplify urban, cultural, and Latino/a/x histories.

Globally, insurance premiums reached $7.9 trillion in 2024. Of that, the United States accounts for $1.7 trillion, more than the entire GDP of Mexico. The majority of that money comes from American auto, homeowner, and commercial insurance policies, also known as property and casualty insurance. And, the State of California, the fourth largest economy in the world, accounts for the largest market share. If the United States is the “home of the automobile,” as described by the Zurich Insurance Group’s corporate history, then California, a state shaped by automobile ownership and dependency, is the foundation.[3] One both exceptional, but also telling of larger urban issues facing communities across the United States, especially those many Latinos call home.

Focusing on automobile insurance in California, the topic of my current book project, reveals a cultural history of race, redlining, and how those viewed most unfavorably by risk assessment models, from urbanites to farmworkers, worked against great odds to change the game. Of how they sought to shape an invisible infrastructure of the road. As a group whose mobility has been criminalized for much of the state’s history, as demonstrated acutely in recent months, Latinos have often been at the center of these debates. One such example is the California Supreme Court case Escobedo v. the Department of Motor Vehicles (1950) and the laws that brought us there.

First passed in 1929, the state’s “financial responsibility law” essentially required Californians to buy automobile insurance if they wanted to operate a vehicle. Similar laws were being passed throughout the country in the same period. African American critics were the earliest to publicly argue that not all drivers could comply with this so-called “responsibility” law for both prejudicial and financial reasons. That is, they charged, insurers either refused to sell people of color policies or they did so at prohibitively high rates. In 1942, Spanish-language journalist Jose Garduño brought the issue of insurance discrimination to Spanish-language readers. He described a man, Mr. Corona, who purchased automobile accident insurance but had his policy cancelled soon afterwards. Why? Because he was Mexican. The company asserted that in cases where an accident involving a Mexican national was sent to trial, “the judges will likely feel prejudiced towards the nationality of the sued.” In light of the anticipated losses, whether the driver was at fault or not, Mexican motorists were placed on a “prohibited list” of policyholders.[4] That is, they were deemed too risky by insurers.

As concerns with traffic safety increased in the post-World War II era, the California Assembly looked for legislative solutions that, while well intentioned, furthered the strain on drivers who were denied insurance. Specifically, they passed a new bill (AB 1819) that expanded the state’s insurance requirements. Augustus Hawkins, the only Black member of the Assembly, attempted to exempt drivers who were racially excluded from purchasing insurance, but his amendment failed. Despite warnings from the Attorney General that the law risked “an abuse of police power and violated the ‘due process’ clause of the Constitution,” the bill received enthusiastic support and was signed into law.[5] The first test of the law would come from a Mexican gardener.

On a summer day in 1948, Pedro Escobedo loaded his truck with equipment after tending to the lawn and garden of a Pasadena family. It was a familiar drive from his home, one taking him past the ranch houses of San Gabriel and towards the bungalows of Pasadena, the birthplace of the Rose Parade. He spent a lot of time in his truck, which tripled as transportation between the households he serviced, a mobile office, and storage for his tools. Escobedo was approaching a public intersection on his way between jobs when his car collided with an incoming vehicle. If the accident were not bad enough, he had the misfortune of crashing on the first of July, the date the “Security Following Accident” provision (formerly AB 1819) went into effect.[6]

Like many drivers on California roads, Escobedo was uninsured. A few weeks following the accident, he received notice that unless he deposited a security of $2,800, his driving privileges would be suspended. That was the equivalent of nearly a year’s wages for Escobedo, who made $60 a week cleaning and renovating gardens. Unable to post the amount, the DMV suspended Escobedo’s license.

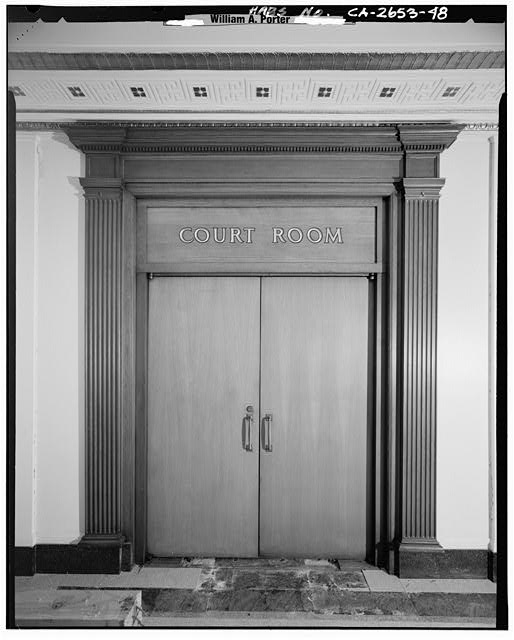

Escobedo turned to the courts with a formidable advocate in his corner. David C. Marcus had litigated several of the most groundbreaking cases involving Mexican American civil rights that decade. Gaining national attention, Marcus had recently won Mendez v. Westminster (1946), which found the arbitrary segregation of Latinos in schools unconstitutional. Marcus sought a writ of mandamus, or a court order compelling the DMV to refrain from an illegal act, from the Supreme Court of California that would reinstate Escobedo’s license. He claimed that the new law denied Escobedo both due process and equal protection under the state and federal Constitutions. He underscored that the statue provided no provisions for a hearing or means of recourse before the suspension, that the DMV was delegated judicial power absent a standard way to determine the amount of the security required, and that it was arbitrarily discriminatory, for example favoring the wealthier who could afford insurance over the poor who could not.

Escobedo v. Department of Motor Vehicles was decided on September 13, 1950. In a 4-2 split, the court upheld the new law. The press described it as a defeat of Escobedo’s claim that “the act discriminated against the poor.”[7] Judge Jesse W. Carter and Judge Douglas L. Edmonds each wrote dissenting opinions, disagreeing with the majority opinion. Judge Carter reasoned that for a court hearing to occur after a license suspension, and not before, there must be a “compelling public interest.”[8] Judge Edmonds echoed Judge Carter’s concerns with constitutional violations, resulting in the loss of a “valuable property right” (the right to drive) without due process. He explained that once issued a license, workers like Escobedo depend on them for essential income. They take on the form of a property right. Although case law favored these economic based arguments, the judge also gestured towards the wider and intertwined stakes of access to an automobile for modern people living in the urban metropolis. “Today the social and economic circumstances of many persons” Carter wrote, “have placed a motor vehicle in the category of necessity.”[9] But under the new law, motor-dependent workers like Escobedo had no protection from an unconstitutional suspension.

Over two decades later, the Escobedo decision was overruled in a unanimous decision by the California Supreme Court in another case involving Latino drivers.[10] But hindsight did nothing for Escobedo. It did nothing for the nearly 20,000 motorists who were required to show proof of financial responsibility without a hearing in the first four months after the law went into effect. It brought no relief to the over 6,500 drivers who had their licenses revoked as a result of the law. Nor did it ease the hardship of the over 1,300 motorists a month who received citations for suspension, including communities of color who were routinely denied insurance, like Mexican nationals, Japanese Americans as internment ended, and African Americans living in central and south Los Angeles.[11]

Latinos appear in many of the major turning points in California automotive insurance history, from class action suits by Central Valley farmworkers challenging language discrimination to East Los Angeles Catholics mobilizing around the very formulas by which insurers set their rates. This history is reflective of a larger social reckoning occurring in communities across the country concerned with insurance, including “redlining,” wherein drivers pay higher premiums or are denied automotive insurance outright based on their geographic residence. More so, it is shaped by calls for “mobility justice,” a term used both in academic and activist circles to refer to equity in the ability to be mobile or stay put, or as described by the multiracial collective the Untokening “to move easily, fairly and unafraid.”

Being in Los Angeles means living with the contradictions of mobility and immobility in the twentieth century. It means telling my concerned 7-year-old son that grandma will not be taken away by ICE while we drive by soldiers holding rifles in front of the federal building near UCLA. It means watching registration tags burn brightly on license plates, as they signal drivers with expired insurance and make them vulnerable to police confrontation, even as California has become more consumer-oriented following voter reform. It means vigilance as a new Supreme Court decision allows federal agents to treat certain vehicles, like those marking their drivers as gardeners or construction workers, as justification for detainment. For those attending the Urban History Association meeting, whether from near or far, we are embedded in these contradictions. As we sit with these tensions, perhaps, we might learn something from insurance, which at its core asks two central questions: To whom are we responsible? And what risks are we willing to take?

This research is generously supported by the UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute, https://latino.ucla.edu/about/.

Genevieve Carpio is an Associate Professor in UCLA’s César E. Chávez Department of Chicana/o Studies. She is author of Collisions at the Crossroads: How Place and Mobility Make Race (University of California Press, 2019).

Featured image (at top): Contextual photograph, view looking west from Consuelo Street looking towards Administration Building (HABS CA-2800-AA) and Casa Consuelo (HABS CA-2800-AM) – Los Angeles County Poor Farm, 7601 Imperial Highway, Downey, Los Angeles County, CA, David Lee, photographer, 2015, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.

[1] Madeline Wander, “Mobility and Racial-Spatial Isolation in Suburbs” (PhD diss., University of California Los Angeles, 2025).

[2] See also Eric Avila’s commentary on Almaraz and transportation histories more broadly in Folklore of the Freeway: Race and Revolt in the Modernist City, University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

[3] Karl Lüönd, Inspired by Tomorrow, Zurich-125 Years History and Vision of a Global Corporation, Editions NZZ, Zurich, Switzerland: Zurich Insurance Company, 1998, p. 105.

[4] Jose Garduño, “Otro Caso de Prejuicio Racial Anti-Mexicano,” La Opinión, April 12, 1942.

[5] California Deputy Attorney General Wilmer W. Morse to Governor Earl Warren, Inter-Departmental Communication Re: A.B. 1819. July 2, 1947. GCBF Governor’s Office, California State Archives Office of the Secretary of State Sacramento. Pg. 1.

[6] Escobedo v. State, Dep’t of Motor Vehicles, 35 Cal. 2d 870, 222 P.2d 1, 1950 Cal. LEXIS 388 (Supreme Court of California September 13, 1950).

[7] “On 4 to 2 split: Drivers’ Financial Responsibility Law Upheld by Supreme Court,” Daily Breeze, Redondo Beach, California, September 14, 1950. P. 13.

[8] Escobedo v. State, Dep’t of Motor Vehicles, 1950.

[9] Escobedo v. State, Dep’t of Motor Vehicles, 1950.

[10] Rios v. Cozens, 7 Cal. 3d 792, 499 P.2d 979, 103 Cal. Rptr. 299, 1972 Cal. LEXIS 225 (Supreme Court of California August 15, 1972).

[11] Escobedo v. State, Dep’t of Motor Vehicles, 1950.

I never realized that access to an automobile could be framed as a property right tied to income and livelihood. This adds a whole new layer to urban history.

LikeLike